Eyewitness memory (child testimony)

An eyewitness testimony is a statement given under oath by a person present at an event who can describe what happened.[1][2] During circumstances in which a child is a witness to the event, the child can be used to deliver a testimony on the stand. The credibility of a child, however, is often questioned due to their underdeveloped memory capacity and overall brain physiology. Researchers found that eyewitness memory requires high-order memory capacity even for well-developed adult brain.[3] Because a child's brain is not yet fully developed, each child witness must be assessed by the proper authorities to determine their reliability as a witness and whether or not they are mature enough to accurately recall the event, provide important details and withstand leading questions.

Brain development associated with eyewitness testimony

Brain development is an after-forward process; from the occipital lobe (visual), to the temporal lobe (sensory, auditory and memory), to the parietal lobe (motor, pain, temperature, and stress), and finally to the frontal lobe (language, reasoning, planning, and emotion).[4] All of these brain regions work together to build up our eyewitness memory.

Generally, infants are born with formed brain systems and their brains develop very rapidly during the first three years.[5] The size of a newborn brain is approximately 400g and continues to grow to 1100g at the age of three, which is close to the size of an adult brain (1300-1400g).[6]

Although infants are born with a properly formed brain, they are still far away from full development. The glial cells, which play a vital role in proper brain function (e.g. insulating nerve cells with myelin), keep growing to divide and multiply after birth.[7] However, to have a fully developed eyewitness memory, the development of gray matter, white matter, the dentate gyrus and density of synapses are highly necessary.

The volume of white matter starts its linear increase from age four to 20, but cortical gray matter is decreases in the parietal, occipital and temporal regions starting from age four, continually changing until after age 12.[8] The development of the dentate gyrus starts forming at 12 to 15 months in the hippocampus, which is essential for the formation of declarative memory in eyewitness testimony.[5] After the formation of the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus, the density of synapses in the prefrontal cortex, which is involved in eyewitness memory, is peaks in its development during 15 to 24 months, changing until the age of adolescence.[5]

Major brain regions necessary for eyewitness performance

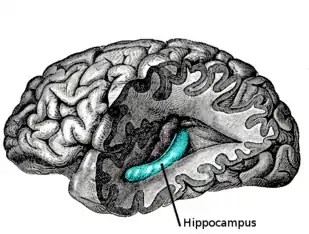

Hippocampus

The hippocampus is one of the brain structures located within the medial temporal lobe and is considered one of the main structures of the brain associated with eyewitness testimony because it is the area that is important for the formation of long term memories.[9] Declarative memories are long term memories that can be consciously remembered, which include: specific events and factual knowledge.[9] Eyewitnesses use declarative memories, specifically episodic memory when they are asked to recall specific events that took place in the past. For example, "Do you remember what the doctor said to you last time you visited him?" Research on children as eyewitnesses found that children do not have accurate long term memories for past events.[10]

The hippocampus is not yet completely developed until 2–8 years of age; however, there are mixed findings for the exact moment when the hippocampus stops maturing.[11] Though the hippocampus may stop maturing at a certain age, behavioural evidence shows that declarative memories are known to develop from childhood up until adulthood.[9]

A study looking at age differences in which children can remember episodic memories (e.g. their first day of school, attending a friend's birthday party), elementary and preschool students were questioned about delay interval in past experiences and found significant differences in what children recall. Elementary school students were more successful at this task than preschoolers. Overall, children need more prompts to remember past events and recall fewer details than older children.

Stress also appears to disrupt the function of the hippocampus as it reduces the likelihood for details to be remembered in a logical sequence.[10] Since most children are asked to recall stressful events for eyewitness testimonies, they may explain them in fragmented sequences of events.

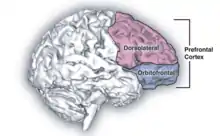

Prefrontal cortex

The prefrontal cortex is another brain region involved in eyewitness testimonies. Its function in relation to memory is to create memories that are vivid and that have a lot of contextual detail.[9] Research in the Journal of Law and Human Behaviour found that the ability for child eyewitnesses to accurately recall details of events increases with age, as did the ability to answer specific questions, identify the confederate and resist suggestion. Studies have found that children tend to give few details of the event and sometimes distort them in eyewitness testimonies.[10] This brain region is one of the last regions to develop.

Short term memory occurs in the prefrontal cortex. Working memory is another process that relies on the prefrontal cortex.

Temporal lobe

The temporal lobes are involved in several functions of the body including: hearing, meaning, auditory stimuli, memory, and speech. They also play a role in emotion and learning [12] and are concerned with processing and interpreting auditory stimuli. This is a major location for memory storage and is associated with memory skills.

Parts of the temporal lobe show late maturation. These regions are of the last brain regions to mature.[13] The gray matter in the temporal lobe continues developing until it reaches its peak development at age 16 for both males and females.

Amygdala

The amygdala is located deep within the temporal lobe of the brain and is involved in the acquisition and retrieval of information on highly salient events.[14] It is also involved in several functions of the body, which include determining what and where memories are stored in the brain. The determination of what/where memories are stored is dependent on how big of an emotional response an event evokes.[14] This is related to eyewitness testimonies because young children usually have poorer recall for details of events, but when an event evokes a highly aversive response (unpleasant, arousing), they tend to remember it.

The amygdala does not stop developing until late adolescence. Research studies have found that in normal developing children, the volume of amygdala increases substantially between seven and 18 years of age.[15] This influences how children perform as eyewitnesses because children will have poorer skills for storing and recalling memories of events prior to the age of seven.

Short term memory

Short term memory is defined as the ability to store information for a short period of time. If it is rehearsed enough, it will be transferred into long term memory. This is important to know in regards to eyewitness testimonies because children have problems transferring short term memories to long term, as discussed previously.

Overall, there are a number of differences in memory among adults and children. With regards to short term memory, a child's capacity to store items is less than that of an adult. More specifically, evidence has shown that a five-year-old can only store up to five items in short term memory, whereas adults are able to store around seven items.[16] This can play a role in how accurate a child's memory performance is in comparison to an adolescent or an adult's recall of the same crime scene.

The amount of time elapsed from when the child witnessed the scene to when they give their testimony is also a contributing factor to how short term memory influences the accuracy of their recall as an eyewitness.[17] It was found that a child's short term memory is more susceptible to interference as the amount of time increases between the event and the testimony.[17] This can lead to misinformation on the child's part and an inaccurate recall of events.[17] One explanation for this is that information that is learned shortly after the event is combined with information that is being temporarily stored in short term memory, having yet to make it into long term memory, causing contradictory traces to coexist.[17]

Long term memory

Eyewitness testimonies in long term memory can be influenced by the loss of information during the process of encoding and storing event details into long term memory.[10] According to the information processing model, if sensory information about an event is not directly transferred from short term memory into long term memory, the information is difficult to retrieve. Research has also found that the rate of transfer of sensory information from short term to long term memory is related to age of the witness. Older children have higher success rates in transferring memory from short term to long term than younger children, which plays a role in why younger children have poorer recall in eyewitness testimonies.[10]

Selective attention also contributes to the impairment of younger children's information encoding process.[10] Namely, if children's attentions are disrupted by an object (e.g. a gun) while witnessing a crime, they might be unable to fully encode all of the details, resulting in poor recall of the event later on in life.

Factors affecting eyewitness testimony

Retroactive interference

Retroactive interference encourages incidental forgetting, in which the newly learned information impairs the retrieval of previously learned knowledge, especially for similar and related information.[18] For example, if you have already learned about proactive interference and recently learned new information about retroactive interference, the knowledge you learned about retroactive interference has the tendency to impede the retrieval of the knowledge of proactive interference.

The passage of time is not of major importance but still has relevance to retroactive interference. The results of a study on rugby players by Hitch and Baddeley showed that trace decay contributes relatively nonsignificant effects on retroactive recall.[19]

Consolidation of the previously learned knowledge and the new information is important.[20] If the previously learned knowledge is well consolidated in memory, the impeding influence caused by the new encoding has less effect; inversely, if the newly learned information is better encoded than the old knowledge, the interference is greater. This is especially true when the previously learned knowledge is simply encoded in short-term and working memory—basically, the low level of consolidation.[19] The similarity between the new information and old knowledge can have an effect on performance as well. When the recently acquired information is phonologically and semantically similar with the known knowledge, the rate of retroactive interference is increased through confusion between the two materials.[21][22]

The encoding process, retrieval traces and contextual cues of the newly learned information play significant roles in impairment. The ways that information is encoded can impair the retrieval performance of that information. The better encoding, the better retrieval will be, especially under circumstances of appropriate retrieval traces and sufficient contextual cues.[23] How to retrieve the encoded information, a.k.a. retrieval strategy, is also essential for preventing retroactive interference. The failure in binding and tracking the contextual information has an increased impact on the retroactive interference effect.[24]

Retroactive interference can also be attributed to personal experiences and memories. The schematic knowledge in memory is useful in forming expectations and drawing inferences for understanding, but it is also able to cause distortion and interference when the encoding information is inconsistent with what has been stored.[25] In addition, the extent of knowledge stored in memory affects the accuracy of the encoding and storing of information.[26] Knowing a lot about a subject helps to improve the accuracy of other related subjects. A lack of essential experience can interfere with the processes of learned knowledge and increase the risk of retroactive interference when learning new information about the already learned subject.

Memory capacity involves the state of maturity and plasticity of the brain and can impair memory performance especially in terms of interference.[4] The development of brain function has a great influence on memory capacity which is responsible for the performance of memory. This includes verbal expression, object recognition, etc.

In children, memory capacity, source monitoring, and language development are limited because their brains are not yet mature. These limitations enhance the effect of retroactive interference on the accuracy of a child's eyewitness testimony. For instance, a five-year-old child is generally able to tell the genital contact of a sexual abuse perpetrator, but it is difficult for the child to identify other features such as facial features and clothing due to their underdeveloped memory capacity.[10] The undeveloped conceptual functions of a child's brain restricts their capacities in object recognition, social cognition, language, and human capacity (the ability to remember the past and imagine the future), and impairs the retrieval and accuracy of their eyewitness memory.[23]

Due to their young age, children have less personal experience, making them vulnerable to impairments from retroactive interference. Therefore, when used as eyewitnesses, it is less possible for them to encode and store the features of the criminal in an appropriate or sufficient way, which impedes the accuracy of the eyewitness retrieval.

Stress and trauma

- See also: Stress and Psychological trauma

There are many reason why children eyewitness testimonies may not be completely accurate, one of which could be stress and trauma. When children experience a traumatic and stressful event, their ability to accurately recall the event becomes impaired.

The American Psychological Association often claims that emotional events are remembered less accurately than details of neutral or everyday events. Their explanation for why stress and trauma could impair memories under high emotional arousal is a decrease in the available processing capacity which leads to lower memory processing.[27]

Stressful events can also have positive effects on children. Physiological evidence indicates that stressful events are retained particularly well the more children experience positive events in their lives.[28]

Other theorists have relied on The Yerkes-Dodson Law for explaining the effects of stress on a child's memories. The Yerkes-Dodson Law states that too little or too much stress is associated with a decline in memory. Too much stress can narrow someone's attention for stressful memories but aid in consolidation so that details are attended to. Goodman gave inoculations to 76 children between the ages of three and seven and found that those who were most severely distressed by the experience (those who screamed, cried, struggled) later remembered more about the event and were more resistant to suggestion than those who did not experience distress.[28]

In order to help reduce stress and trauma to the child, some studies have shown that good social support during the interviewing process can help children reduce their anxiety. If an interviewer is supportive by smiling, nodding his head and compliments the child during the interviewing process the child's anxiety decreased by a decent margin. The study also showed that the less supportive an interviewer was, the higher the child's anxiety rose.[29]

Early research has studied the impacts of emotion on memory. Sigmund Freud used his psychoanalytic approach to study people with hysteria. Freud found that people are constantly confronted with thoughts and some of the memories are too painful, so people become repressed.[30]

Another method by Kuehn analyzed the data from police reports about victims experiencing traumatic events. He looked specifically at how capable these victims were in being able to provide a description of the traumatic event in a police report. These victims experienced two homicides, 22 rapes, 15 assaults and 61 robberies, respectively. He found that victims of robberies were able to provide more detailed description for the events than did victims of rape or assault. He also found that people who were injured provided more less of description than non injured people.[30]

Stress and trauma can also cause create other problems in eyewitness testimonies such as repression. Repression influences eyewitness testimonies because if a child goes through a stressful or traumatic event they will sometimes repress their memories. According to Freud's theory on repression, a repressed memory is the memory of a traumatic event unconsciously retained in the mind, where it is said to adversely affect conscious thought, desire, and action. As a result, children will have trouble recalling this information or accessing it consciously. If a child who has witnessed a traumatic event is used as an eyewitness, they may have a harder time recalling the event due to the possibility of memory repression.

According to the journal of Law and Human Behaviour, children who have been through traumatic events will find it harder to remember a regular event as opposed to a non-traumatic event. In a study conducted by Goodman, they found that non-abused children were more accurate in answering specific questions and made fewer errors in identifying an unfamiliar person in pictures.[31]

Intelligence

Another factor that has been studied as a contributing variable in the accuracy of child eyewitness testimony is intelligence. Individual differences in intelligence, based on IQ, have been used to explain variances in memory performance among children giving eyewitness testimonies.

The ability for a child to give a free narrative of what happened involves the practice of episodic memory and working memory, which are both influenced by an individual's capacity to cognitively process events.[32] A child's fluid and crystallized intelligence are theorized to predict memory recall.[32] Evidence has shown that higher verbal intelligence is positively correlated with memory performance and negatively correlated with suggestibility in children.[33]

Further analyses of research concerning intelligence and free recall have shown that there are relatively large differences in intelligence when a positive correlation between recall and intelligence is demonstrated.[34] This implies that intelligence significantly influences child eyewitness memory when comparing high and low levels; however, small differences in intelligence are not significant.[34]

Another finding in the influence of intelligence on a memory recall in children is that it seems to be age-dependent.[34] Differences in age group explains the variance in which intelligence has an effect on memory performance. Older children have higher correlations of intelligence and recall, whereas chronological age is more significant of a factor than intelligence for young children's eyewitness memory.[34] More specifically, a study examining the influence of fluid intelligence on recall of children's eyewitness memory regarding a videotaped event found that there was not a positive relationship between fluid intelligence and free narrative for six- and eight-year-olds; however, the positive relationship was present for ten-year-olds.[34]

Likewise, in studies of real cases of children testimony, the general finding is that intelligence is a considerable predictor for witness reports for children in their late elementary school years, but not for children up to the age of six.[33] Therefore, the effect of individual differences in intelligence on eyewitness memory increases with the child's age.[34]

The range in children's intellectual capacities may explain the positive relationship between intelligence and eyewitness memory.[33] Intellectually disabled children and children with below average to very low IQ's have been included in studies examining the influence of intelligence on memory recall. It was found that when giving an eyewitness testimony, there is a stronger positive relationship between intelligence and recall for intellectually disabled children, with recall accuracy being poorer with children of lower IQ than for children with average or high intelligence.[35] A possible explanation for this may be that in comparison to a child of mainstream intelligence, children of lower intelligence encode weaker memory traces of events.[35]

Another explanation is that individuals with intellectual disabilities have poorer cognitive and language functioning, which would directly impact their performance on memory and language tasks.[36] A study examining the extent to which the degree of intellectual disability (mild to moderate) has an effect on the relationship between intelligence and witness memory found that there was no significant difference in same-aged children with mild intellectual disabilities (IQ 55-79) and children with normal intelligence (IQ 80-100). Individuals with moderate intellectual disabilities (IQ 40-54) performed significantly worse on almost every eyewitness measure.[37]

Suggestibility

In general, the judicial system has always been cautious when using children as eyewitnesses resulting in rules that demand all child testimonies be confirmed by designated officials prior to its acceptance as evidence in the court of law.[38] One of the reasons for this partiality is suggestibility—a state in which a person will accept the suggestions of another person and act accordingly.[39] With regards to court proceedings, a child's testimony or recollection of an event is especially vulnerable to leading questions.[38]

Although suggestibility decreases with age, there is a growing consensus that the presence of an interplay between individual characteristics and situational factors may affect suggestibility, in this case, of children. This explains why children of the same age may significantly vary in levels of suggestibility.[40]

There are several factors that contribute to a child's suggestibility. Age-related differences are often synonymous with developmental differences, though the latter, when not comparing two different age groups, has no effect on a child's suggestibility.[41] Basically, individual differences between children of the same age group do not play a significant role in a child's level of suggestibility. If there is a difference in suggestibility levels of children that are of the same age, they are most likely due to maturational differences in specific cognitive skills.[40]

Studies also show that it is not the leading questions themselves that can alter a child's recall of the event, but the event in question. When children are questioned about true events that they actually participated in, they are much more accurate with their answers. With suggested events in which the questioner is suggesting the child may have been involved, children become more suggestible and easier to influence. Younger children also have a larger tendency to change their answers when making “yes,” “no,” or “I don’t know” statements.[40]

It is yet to be determined whether there is a particular age or level of specific cognitive functioning at which suggestibility becomes more of a universal trait or characteristic; However, a study involving four-year-olds suggests that due to their development of theory of mind, this may be close to the age at which suggestibility begins its ‘trait-like’ transition.[40]

Emotion can also make children more suggestible. When using sad stories, children are much more vulnerable to misleading questions than when using angry or happy events. In an experiment, when asked to recall a sad story previously read to them, children were much more descriptive and detailed when answering misleading questions, as opposed to when regular, stories were used.[42] Very similar results were found in a separate experiment in which stress was induced in children.[43]

Children were also more likely to agree with misleading questions and more likely to incorporate fabricated details when asked to recall the event. In this experiment using sad, angry or happy stories, it is at age six that the researchers deemed the average age at which suggestibility levels off.

As with most factors that elicit suggestibility, susceptibility to emotional influences decrease with age. Possible reasons for this may be the increase in narrative skill, knowledge, memory abilities, as well as the ability to properly encode memories. It is also implied that older children may be less trusting of adults’ omniscience and more willing to contradict them.[42]

In 1999, Ceci and Scullin developed the Video Suggestibility Scale for Children (VSSC), which measures individual differences in suggestibility in preschool children.[44] The scale was administered to children of 3–5 years of age.

The results suggested that children tend to respond affirmatively to suggestive questions and change their answers in response to negative ones. Older children were able to recall the events in the video better than younger children, but were also more likely to shift their answers in response to negative feedback. Overall, this scale and study supports Gudjonsson's view that there are at least two basic types of interrogative suggestibility.[45]

Source misattribution

The concepts of source monitoring and source misattribution have been implicated as a reason for the construction of inaccurate memory reports. Source monitoring refers to understanding the origin of one's memories. Source misattributions are issues in retrieval in which the subject struggles to separate two or more sources of memory; it is not an issue necessarily with the memory itself. In other words, source misattributions are errors in source monitoring. The subject may have trouble discriminating between his or her actual perception of an event and their imagined version of these memories (Ceci et al., 1994). Some research suggests that children have more issues with source misattribution compared to adults. Children as old as nine years may have difficulty in discriminating between things they actually did and things that they imagined themselves doing (Foley & Johnson, 1985). Ceci et al. (1994) researched source monitoring and source misattributions among pre-school aged children. 96 pre-school aged children from central New York State were chosen to participate. After the main group of children was selected, they were divided into smaller groups based on their ages: the younger group consisted of three- and four-year-olds and the older group consisted of five- and six-year-olds. To carry out the experiment, the children's parents were interviewed to find out about both positive and negative events that did indeed occur in the child's life. The parents were then asked to verify what certain events did not occur in their child's life. Following the parental interview, the children were interviewed and shown a list of events that happened to them and events that did not happen to them. The events that did actually happen to them were quite salient and the events that did not happen to them were very specific. Of the events that did not happen to the children, one of them described the child getting his or her hand caught in a mousetrap and then going to the hospital to get it removed. The other one entailed going on a hot air balloon ride. The children were asked to decide which events actually happened to them and which ones did not. These interviews with the children happened on about seven or eight occasions, each spaced out by approximately a week. The spacing of the interviews is important, as the researchers used timing as a variable that affects source monitoring. At the final interview, a novel interviewer that the children had not met before asked them to elaborate as much as they could about all of the events, both real and imagined. A new interviewer was used so that the answers the children gave were neutral and not influenced by previous interviewers in any way. They were also asked to rate their confidence level for every detail given about each event.

Ceci et al. (1994) hypothesized that the children would confirm the events that did happen and deny the false events that did not happen. However, this was not the case in their findings; both groups of young children had fallen victim to false memories. When analyzing the results for the two different age groups, the effect of age becomes even more apparent. The children from the 3- and 4-year-old group confirmed false events almost twice as often as the 5- and 6-year-old children. To test the child's apparent credibility, the researchers had over 100 professionals in the field of psychology view recordings of the children during their final session recounting both the actual and false memories. As it happened, many of these professionals were fooled by the children's recounts and were unable to distinguish the false memories from the real ones (Ceci et al., 1994).

Script-based inferences

Erskine, Markham, and Howie (2001) discuss script-based inferences and their effects on memory retrieval and eyewitness testimony. Scripts are schemas for specific events that are constructed from experience (Lindsay, J., 2014). For example, when you walk into a restaurant, you generally know to tell the host or hostess the number of people in your party; once you are seated at your table, you know you must decide what to order. These commonly known actions are part of the general restaurant script. Scripts are usually beneficial in that they help organize one's thoughts and they facilitate a better understanding of a situation (Abelson, 1981). However, these script biases can also have effects that are damaging in the retrieval of accurate memories. Scripts can lead people to report details of events that did not happen, even if those details fit with the script of the event.

Erskine, Markham, and Howie (2001) studied how scripts can affect accurate memory retrieval. A group of 60 5- and 6-year-olds and a group of 60 9- and 10-year-olds were shown one of two slide sequences portraying eating at a McDonald's. McDonald's was chosen because it is a script that most American children reliably have in their cognition starting from around age 4. Half of the younger group and half of the older group were shown a slide sequence in which three script-central details were left out of the sequence. A central detail could be ordering the food at the counter or eating the food in the restaurant. The other half of the participants were shown a slide sequence in which three script-peripheral details were left out. A peripheral detail could be spilling a drink or tying a shoelace. These details did not infringe upon the traditional McDonald's script, but they are not inherently a central part of the script either. Once the children had seen the slide sequence, they were placed into one of two delay conditions: within 90 minutes of viewing the slides, or a week after viewing the slides. After the delay, they were asked to recall the slide sequence.

This study provided evidence that children will utilize scripts to make inferences about parts of a story (Erskine, Markham, & Howie, 2001). The researchers found that children in the younger group, the 5- and 6-year-olds, used incorrect script inferences more often than the children in the older group, the 9- and 10-year-olds. Additionally, the younger children did worse in both the immediate recall condition and the week-long delay condition. Both age groups used significantly more script inferences when they were asked to recall the slide sequence a week later compared to the 90-minute delay. These results were found for recall of script-central details. Neither the older nor the younger groups made a significant number of errors in recalling the script-peripheral details.

Socially encountered misinformation

Socially encountered misinformation also has the potential to distort children's memories. The misinformation effect occurs when our recall of a memory becomes distorted because of new information introduced after the initial event (Weiten, 2010). This is an extremely important topic to research, as in the judicial process misinformation is often disclosed during the initial interview phase. The interview is also the phase in which witnesses, specifically children, are most susceptible to suggestibility. A study conducted by Akehurst, Burden, and Buckle (2009) investigated the impact of socially supplied misinformation on children. Children witnessed an event and subsequently were exposed to two different types of misinformation about the event they saw: one from another person, a co-witness to the event, and one in the form of written information in either a newspaper or a magazine. The researchers thought that the children who received misleading information, both written and verbal, would be more suggestible than those who were not exposed to misleading information. First, they hypothesized that the children who were exposed to the misleading verbal information would be more susceptible to suggestion compared to the children who were exposed to the written misinformation (Akehurst, Burden, and Buckle, 2009). In addition to the different methods of delivery of the misinformation, Akehurst, Burden, and Buckle wanted to investigate the effects of time delay on the suggestibility of children. They hypothesized that after three months, the way in which the misinformation was delivered to the child would not matter as much, and the strength of the memory trace would become more prominent.

To carry out the experiment, Akehurst, Burden, and Buckle had a total of 105 participants aged between 9–11 years. These participants were shown a video of a woman arriving at the dentist for dental surgery, checking in at reception, and having her teeth looked at by the dentist. The woman was portrayed as afraid of the dentist, so the video had a negative emotional quality. After viewing the video, the children were given misinformation about the event either verbally or written based on the condition that they were placed in. In the written narrative condition, misinformation was introduced, such as mislabeling the color of the woman's coat or mentioning that she was wearing glasses when she was not. In the co-witness, verbal misinformation condition, a confederate recited the same misinformation that was in the narrative condition. The only difference between the two conditions was the method in with the misinformation was delivered. The participants were interviewed twice following the receipt of the misinformation: once immediately after, and then three months later. In these interview sessions, the participants were asked to answer questions about the event solely based on what they had seen in the video.

Akehurst, Burden, and Buckle's (2009) study of misinformation provided evidence that 9- to 11-year-old children can be susceptible to suggestion and misinformation under the right conditions. The children were most susceptible in the interview right after they were given the misinformation, both verbally and written. This finding corresponds to their second hypothesis. Additionally, Akehurst, Burden, and Buckle (2009) found that children in the condition where the misinformation was provided socially and verbally via a confederate were more susceptible to recalling the misleading information compared to the children who received the misinformation in a written narrative, which corresponds to their first hypothesis. According to Tajfel and Turner (1986), people are more likely to believe information that they receive through a social route because of a need to affiliate with others. Children are specifically susceptible to social misinformation because they generally believe in the authority of adults simply based on the age difference. Thus, the effects of misinformation can be reduced if the misleading information is not provided socially (Akehurst, Burden, and Buckle, 2009).

From childhood to adolescence

In general, adolescents are far more trustworthy eyewitnesses than children. They are already fully mature in terms of cognition (i.e. narrative skills, memory recall and encoding, etc.) Researchers found that the ability to recall single pieces of spatial information developed until ages 11 to 12, while the ability to remember multiple units of information developed until ages 13 to 15. However, strategic self-organized thinking, which demands a high level of multi-tasking skill, continues to develop until ages 16 to 17.

The frontal lobe and prefrontal cortex continues to develop until late adolescence, depending on the complexity of the task. When accomplishing complicated tasks, teenagers are still developing the cognitive skills necessary to efficiently manage multiple pieces of information simultaneously. These skills improve over time as the connections between brain cells become more refined, enabling more information to be simultaneously managed.[46]

In regards to credibility as an eyewitness, adolescents are no longer easy to manipulate and are not suggestible like young children. This is due to obvious cognitive factors, as well as maturation as a person. Young children look at adults as powerful and extremely knowledgeable whereas adolescents are not so intimidated when questioned by adults.[47]

However, this does not mean that adolescents are invincible and impermeable when on the stand. Because adolescents have much more experience in the world, their knowledge may actually hinder their eyewitness performance. When asked about details of a story or movie that was just read or watched, college students were just as likely as sixth graders to produce detailed, but false additions.[43] This study further explains that this is a result of behavioural scripts. They used inferences from what they already knew about people, actions, and situations and acted based on their instincts.

For example, when asked about a movie about cheating on tests, the college students added details explaining why the student cheated although it was not included in the film. They described the thoughts and feelings of the student because they are able to draw from their own separate experiences and knowledge of the situation. However, third graders were found to be less suggestible in questioning due to their limited knowledge as well as their limited script involving cheating.

External links

References

- http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/eyewitness%5B%5D

- http://www.businessdictionary.com/definition/eyewitness-testimony.html%5B%5D

- Loftus, Elizabeth F. (1980). "Impact of expert psychological testimony on the unreliability of eyewitness identification". Journal of Applied Psychology. 65 (1): 9–15. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.65.1.9. PMID 7364708.

- Casey, B.J.; Giedd, Jay N.; Thomas, Kathleen M. (October 2000). "Structural and functional brain development and its relation to cognitive development". Biological Psychology. 54 (1–3): 241–257. doi:10.1016/S0301-0511(00)00058-2. PMID 11035225. S2CID 18314401.

- Bauer, Patricia J.; Pathman, Thanujeni (December 2008). "Memory and early brain development". Encyclopedia on Early Childhood Development: 1–6. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.564.3414.

- Dekaban, Anatole S.; Sadowsky, Doris (October 1978). "Changes in brain weights during the span of human life: Relation of brain weights to body heights and body weights". Annals of Neurology. 4 (4): 345–356. doi:10.1002/ana.410040410. PMID 727739. S2CID 46093785.

- Chudler, Eric H. "Neuroscience For Kids - Brain Development". University of Washington.

- Giedd, Jay N.; Blumenthal, Jonathan; Jeffries, Neal O.; Castellanos, F. X.; Liu, Hong; Zijdenbos, Alex; Paus, Tomáš; Evans, Alan C.; Rapoport, Judith L. (October 1999). "Brain development during childhood and adolescence: a longitudinal MRI study". Nature Neuroscience. 2 (10): 861–863. doi:10.1038/13158. PMID 10491603. S2CID 204989935.

- Ofen, Noa; Kao, Yun-Ching; Sokol-Hessner, Peter; Kim, Heesoo; Whitfield-Gabrieli, Susan; Gabrieli, John D. E. (September 2007). "Development of the declarative memory system in the human brain". Nature Neuroscience. 10 (9): 1198–1205. doi:10.1038/nn1950. PMID 17676059. S2CID 15637865.

- Goodman, Gail S.; Bottoms, Bette L.; Rudy, Leslie; Davis, Suzanne L.; Schwartz-Kenney, Beth M. (2001). "Effects of past abuse experiences on children's eyewitness memory". Law and Human Behavior. 25 (3): 269–298. doi:10.1023/A:1010797911805. PMID 11480804. S2CID 15673909. ProQuest 204157441.

- Wertlieb, Donald; Rose, David (1979). "Maturation of Maze Behavior in Preschool Children". Developmental Psychology. 15 (4): 478–479. doi:10.1037/h0078085.

- Lehr, R. (2011). Brain Functions and Map. Retrieved from http://www.neuroskills.com/brain-injury/brain-function.php

- Gogtay, Nitin; Giedd, Jay N.; Lusk, Leslie; Hayashi, Kiralee M.; Greenstein, Deanna; Vaituzis, A. Catherine; Nugent, Tom F.; Herman, David H.; Clasen, Liv S.; Toga, Arthur W.; Rapoport, Judith L.; Thompson, Paul M. (25 May 2004). "Dynamic mapping of human cortical development during childhood through early adulthood". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 101 (21): 8174–8179. doi:10.1073/pnas.0402680101. PMC 419576. PMID 15148381.

- Adolphs, Ralph; Denburg, Natalie L.; Tranel, Daniel (2001). "The amygdala's role in long-term declarative memory for gist and detail". Behavioral Neuroscience. 115 (5): 983–992. doi:10.1037/0735-7044.115.5.983. PMID 11584931.

- Schumann, Cynthia Mills; Hamstra, Julia; Goodlin-Jones, Beth L.; Lotspeich, Linda J.; Kwon, Hower; Buonocore, Michael H.; Lammers, Cathy R.; Reiss, Allan L.; Amaral, David G. (14 July 2004). "The Amygdala Is Enlarged in Children But Not Adolescents with Autism; the Hippocampus Is Enlarged at All Ages". Journal of Neuroscience. 24 (28): 6392–6401. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1297-04.2004. PMC 6729537. PMID 15254095.

- Davies, Graham; Lloyd-Bostock, Sally; McMurran, Mary; Wilson, Clare (1996). Psychology, Law, and Criminal Justice: International Developments in Research and Practice. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-013858-0.

- McCauley, M., & Fisher, R. P. (1996). Enhancing children’s eyewitness testimony with cognitive interview. Oxford, England: Walter De Gruyter Inc.

- Bower, Gordon H.; Thompson-Schill, Sharon; Tulving, Endel (1994). "Reducing retroactive interference: An interference analysis". Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 20 (1): 51–66. doi:10.1037/0278-7393.20.1.51. PMID 8138788.

- Baddeley, Alan D.; Hitch, Graham J. (1994). "Developments in the concept of working memory". Neuropsychology. 8 (4): 485–493. doi:10.1037/0894-4105.8.4.485.

- Nadel, Lynn; Moscovitch, Morris (April 1997). "Memory consolidation, retrograde amnesia and the hippocampal complex". Current Opinion in Neurobiology. 7 (2): 217–227. doi:10.1016/S0959-4388(97)80010-4. PMID 9142752. S2CID 4802179.

- Hintzman, Douglas L.; Curran, Tim; Oppy, Brian (1992). "Effects of similarity and repetition on memory: Registration without learning?". Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 18 (4): 667–680. doi:10.1037/0278-7393.18.4.667.

- Baddeley, A.D.; Dale, H.C.A. (October 1966). "The effect of semantic similarity on retroactive interference in long- and short-term memory". Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior. 5 (5): 417–420. doi:10.1016/S0022-5371(66)80054-3.

- Hayne, Harlene; Herbert, Jane (October 2004). "Verbal cues facilitate memory retrieval during infancy". Journal of Experimental Child Psychology. 89 (2): 127–139. doi:10.1016/j.jecp.2004.06.002. PMID 15388302.

- Hedden, Trey; Park, Denise C. (2003). "Contributions of source and inhibitory mechanisms to age-related retroactive interference in verbal working memory". Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. 132 (1): 93–112. doi:10.1037/0096-3445.132.1.93. PMID 12656299.

- Whitney, P. (2001). "Schemas, Frames, and Scripts in Cognitive Psychology". International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences. pp. 13522–13526. doi:10.1016/B0-08-043076-7/01491-1. ISBN 978-0-08-043076-8.

- McNichol, Susan; Shute, Rosalyn; Tucker, Alison (November 1999). "Children's eyewitness memory for a repeated event". Child Abuse & Neglect. 23 (11): 1127–1139. doi:10.1016/S0145-2134(99)00084-8. PMID 10604067.

- Aharonian, Ani A.; Bornstein, Brian (2008). "Stress and Eyewitness Memory". In Cutler, Brian L. (ed.). Encyclopedia of Psychology and Law.

- Goodman, Gail S.; Bottoms, Bette L.; Schwartz-Kenney, Beth M.; Rudy, Leslie (1991). "Children's Testimony About a Stressful Event: Improving Children's Reports". Journal of Narrative and Life History. 1 (1): 69–99. doi:10.1075/jnlh.1.1.05chi.

- Davis, Suzanne L.; Bottoms, Bette L. (2002). "Effects of social support on children's eyewitness reports: A test of the underlying mechanism". Law and Human Behavior. 26 (2): 185–215. doi:10.1023/A:1014692009941. PMID 11985298. S2CID 18886695. ProQuest 204162021.

- Christianson, Sven-Åke (1992). "Emotional stress and eyewitness memory: A critical review". Psychological Bulletin. 112 (2): 284–309. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.112.2.284. PMID 1454896.

- Goodman, Gail S.; Golding, Jonathan M.; Helgeson, Vicki S.; Haith, Marshall M.; Michelli, Joseph (1987). "When a child takes the stand: Jurors' perceptions of children's eyewitness testimony". Law and Human Behavior. 11 (1): 27–40. doi:10.1007/BF01044837. S2CID 147369949.

- Fry, Astrid F.; Hale, Sandra (October 2000). "Relationships among processing speed, working memory, and fluid intelligence in children". Biological Psychology. 54 (1–3): 1–34. doi:10.1016/S0301-0511(00)00051-X. PMID 11035218. S2CID 15884885.

- Chae, Yoojin; Ceci, Stephen J. (May 2005). "Individual differences in children's recall and suggestibility: the effect of intelligence, temperament, and self-perceptions". Applied Cognitive Psychology. 19 (4): 383–407. doi:10.1002/acp.1094.

- Roebers, Claudia M.; Schneider, Wolfgang (January 2001). "Individual Differences in Children's Eyewitness Recall: The Influence of Intelligence and Shyness". Applied Developmental Science. 5 (1): 9–20. doi:10.1207/S1532480XADS0501_2. S2CID 144795719.

- Young, Kristie; Powell, Martine B.; Dudgeon, Paul (July 2003). "Individual differences in children's suggestibility: a comparison between intellectually disabled and mainstream samples". Personality and Individual Differences. 35 (1): 31–49. doi:10.1016/S0191-8869(02)00138-1.

- Agnew, Sarah E.; Powell, Martine B. (2004). "The effect of intellectual disability on children's recall of an event across different question types". Law and Human Behavior. 28 (3): 273–294. doi:10.1023/B:LAHU.0000029139.38127.61. PMID 15264447. S2CID 23473430.

- Henry, Lucy A.; Gudjonsson, Gisli H. (2003). "Eyewitness memory, suggestibility, and repeated recall sessions in children with mild and moderate intellectual disabilities". Law and Human Behavior. 27 (5): 481–505. doi:10.1023/A:1025434022699. PMID 14593794. S2CID 36017334.

- Ceci, Stephen J.; Ross, David F.; Toglia, Michael P. (1987). "Suggestibility of children's memory: Psycholegal implications". Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. 116 (1): 38–49. doi:10.1037/0096-3445.116.1.38.

- suggestibility. CollinsDictionary.com. Collins English Dictionary - Complete & Unabridged 11th Edition. Retrieved September 22, 2012

- Scullin, Matthew H.; Kanaya, Tomoe; Ceci, Stephen J. (2002). "Measurement of individual differences in children's suggestibility across situations". Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied. 8 (4): 233–246. doi:10.1037/1076-898X.8.4.233.

- Ceci, Stephen J.; Toglia, Michael P.; Ross, David F. (June 1988). "On remembering… more or less: A trace strength interpretation of developmental differences in suggestibility". Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. 117 (2): 201–203. doi:10.1037/0096-3445.117.2.201.

- Levine, Linda J.; Burgess, Stewart L.; Laney, Cara (May 2008). "Effects of discrete emotions on young children's suggestibility". Developmental Psychology. 44 (3): 681–694. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.44.3.681. PMID 18473636.

- Ceci, Stephen J.; Bruck, Maggie (1993). "Suggestibility of the child witness: A historical review and synthesis". Psychological Bulletin. 113 (3): 403–439. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.113.3.403. PMID 8316609.

- Scullin, Matthew H; Ceci, Stephen J (April 2001). "A suggestibility scale for children". Personality and Individual Differences. 30 (5): 843–856. doi:10.1016/S0191-8869(00)00077-5.

- Gudjonsson, Gisli H. (January 1984). "A new scale of interrogative suggestibility". Personality and Individual Differences. 5 (3): 303–314. doi:10.1016/0191-8869(84)90069-2.

- Luciana, Monica; Conklin, Heather M.; Hooper, Catalina J.; Yarger, Rebecca S. (May 2005). "The Development of Nonverbal Working Memory and Executive Control Processes in Adolescents". Child Development. 76 (3): 697–712. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.2005.00872.x. PMID 15892787. Lay summary.

- Levine, Linda J.; Burgess, Stewart L.; Laney, Cara (May 2008). "Effects of discrete emotions on young children's suggestibility". Developmental Psychology. 44 (3): 681–694. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.44.3.681. PMID 18473636.