FIGO classification of uterine bleeding

The International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) is an international organization that links about 125 international professional societies of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. In 2011 FIGO recognized two systems designed to aid research, education, and clinical care of women with abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB) in the reproductive years. This page is a summary of the systems and their use in contemporary gynecology.

Background

Abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB) in the reproductive years, unrelated to pregnancy, is rarely life-threatening, but is frequently life altering. The symptoms frequently interfere with quality of life and those girls and women afflicted with chronic AUB spend significant amounts of personal resources on menstrual products and medications. Such women are 30 per cent less productive at work, and, consequently, suffer a similar reduction in income.[1][2] For low resource countries, the combination of poor nutrition, lack of access to simple therapy with iron replacement, and the symptom of heavy menstrual bleeding (HMB) are collectively responsible for the global epidemic of iron deficiency anemia, a circumstance that sets up a pregnant population vulnerable to peripartum hemorrhage and its sequellae, including death. The prevalence of AUB in the reproductive years is high; it is estimated that it affects 30% of all women at some time in their lives. Approximately 5% seek care each year; and up to 30% of all visits to gynecologists are for an AUB symptom. The problem of AUB burdens the economy, employers, as well as women and their families. The total annual direct and indirect costs of AUB are estimated to exceed 37 billion USD.[3] There is evidence that, even in developed countries, only about half of those affected actually seeks care, and that many who do are not satisfied with the results.[4] For many, hysterectomy remains a common therapy for those who have access to healthcare.

With the massive worldwide impact of both acute and chronic AUB, the relevance of safe and effective clinical care cannot be overestimated. Although common sense interventions such as iron therapy are often underused in developed countries and frequently unavailable in developing nations, these and related therapies deal with reducing the consequences HMB the symptom, not the cause itself. Abnormal uterine bleeding in the reproductive years comprises a complex set of disorders that include abnormalities in endocrine, endometrial and hemostatic function and a number of structural anomalies that include polyps, adenomyosis and leiomyomas or fibroids. It is important to understand that many of the structural abnormalities may not contribute to the patient’s symptoms – they may lie asymptomatic while the cause or causes of the AUB may be elsewhere.

Determination of the causes of AUB in the reproductive years remains a major challenge for investigators, clinicians and educators. Investigators have to conceive and then execute relevant bench and clinical investigation; clinicians must deal with the patient in their office or hospital and educators of medical students and postgraduate trainees such as residents and fellows are encumbered with the task of providing a mechanism for understanding AUB that facilitates proper investigation and therapy.

For a number of investigators and educators, it became apparent that there were at least two major impediments to dealing with these challenges. The first was a disjointed collection of poorly defined and inconsistently used terms and definitions that undermined effective communication among investigators, clinicians and trainees alike.[5] The second was the absence of a system for classifying the potential causes, or contributors to AUB symptoms in a specific patient. These circumstances lead to difficulties with the interpretation of both basic science research and clinical trials as since specimens and patients could be "contaminated" with potential confounders. As a result, in order to obtain clearly informative basic science as well as translational and clinical investigation, a comprehensive approach to both investigation and categorization was needed.

It was in this context that the FIGO (International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics) Menstrual Disorders Working Group was created. Starting in 2005, a group of experts that comprised those from the FDA, related professional societies and gynecologic medical journals, and representatives from the basic, translational, and clinical sciences were assembled to tackle the issues in a systematic fashion.[6][7]

The FIGO Systems of Nomenclature of Terms and Classification of Causes of AUB in the Reproductive Years

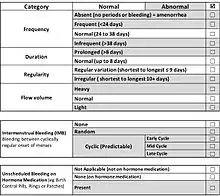

The development of these systems was in large part based upon a process was conducted using RAND's Delphi process. The results allowed for a collective recognition of the disparity and inconsistency in definitions and terminology a circumstance that was a surprise to many. The result of this process was a near unanimous decision to create a new set of descriptive and unambiguous terms that could be translated into a wide spectrum of languages. This process resulted in the first FIGO system; one that provided both definitions and nomenclature of normal and abnormal uterine bleeding using the 5th to 95% percentiles from the available large-scale epidemiological studies.[6][7] Included in this set of definitions was the adoption of the term HMB - a symptom (not a diagnosis) - that was described by the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence as “excessive menstrual blood loss, which interferes with a woman's physical, social, emotional and/or material quality of life”.[8] These findings and recommendations were published simultaneously in 2007, in Fertility and Sterility and Human Reproduction. What is now FIGO’s system of nomenclature and definitions has undergone very modest modifications that will continue to be modified and revised as appropriate.[6][7]

The classification system, known by the acronym “PALM-COEIN”, was developed and first published a textbook,[9] and then, after ratification by the Working Group, was accepted by FIGO in 2010 and finally published together with the nomenclature system and definitions in 2011.[10] Each of the first eight letters stands for a discernable category of disorder, potentially found in an individual with an AUB symptom (Figure 2). The “PALM” categories comprise disorders that are definable by imaging and/or histopathological evaluation (polyps, adenomyosis, leiomyomas, malignancy and hyperplasia), while the “COEI” classifications are not definable structurally (coagulopathies, ovulatory disorders, endometrial disorders, iatrogenic). Coagulopathies require confirmation by laboratory testing, while, at least for the present, ovulatory and endometrial disorders are primarily, and at least clinically, defined by a structured history. Irregular ovulation or anovulation can be supported by a number of laboratory and histopathological assessments, not typically applied in clinical settings. The “N” classification, originally “Not yet classified” now “Not otherwise classified” is reserved for entities that are rare or of undetermined relationship to AUB symptoms.

It is recognized that each of the major categories may include subgroups that are known or suspected to have clinical relevance. The first of these “subclassification systems” was for leiomyomas (Figure 3), recognizing their prevalence and the already existing classification system for submucous leiomyomas first published by Wamsteker et al.[11] and then adopted by the European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology (ESHRE). Added was a category for submucous myomas that make contact with the endometrium but do not distort the endometrial cavity (Type 3), and subclassification for intramural leiomyomas and the various types of subserous myomas.

The 2011 publication,[10] as well as other publications authored or coauthored by the FIGO Menstrual Disorders Working Group, also explicitly included the process of investigation – that is, from the identification that a patient actually has one or more symptoms of AUB (FIGO System 1) to the classification of her condition as categorized by FIGO System 2, the PALM-COEIN System.[12] The systems have been endorsed by a number of national organizations including the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG Practice Bulletin 128).

References

- Cote I; Jacobs P; Cumming DC (2003). "Use of health services associated with increased menstrual loss in the United States". American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 188 (2): 343–8. doi:10.1067/mob.2003.92. PMID 12592237.

- Frick KD; Clark MA; Steinwachs DM; et al. (2009). "Financial and quality-of-life burden of dysfunctional uterine bleeding among women agreeing to obtain surgical treatment". Women's Health Issues. 19 (1): 70–8. doi:10.1016/j.whi.2008.07.002. PMID 19111789.

- Liu Z; Doan QV; Blumenthal P; Dubois RW (2007). "A systematic review evaluating health-related quality of life, work impairment, and health-care costs and utilization in abnormal uterine bleeding". Value in Health. 10 (3): 183–94. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4733.2007.00168.x. PMID 17532811.

- Fraser IS; Mansour D; Breymann C; Hoffman C; Mezzacasa A; Petraglia F (2015). "Prevalence of heavy menstrual bleeding and experiences of affected women in a European patient survey". International Journal of Gynaecology and Obstetrics. 128 (3). pp. 196–200.

- Woolcock JG; Critchley HO; Munro MG; Broder MS; Fraser IS (2008). "Review of the confusion in current and historical terminology and definitions for disturbances of menstrual bleeding". Fertility and Sterility. 90 (6). pp. 2269–80.

- Fraser IS; Critchley HO; Munro MG; Broder M (2007). "A process designed to lead to international agreement on terminologies and definitions used to describe abnormalities of menstrual bleeding". Fertility and Sterility. 87 (3): 466–76. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2007.01.023. PMID 17362717.

- Fraser IS; Critchley HO; Munro MG; Broder M (2007). "Can we achieve international agreement on terminologies and definitions used to describe abnormalities of menstrual bleeding?". Human Reproduction. 22 (3): 635–43. doi:10.1093/humrep/del478. PMID 17204526.

- Excellence NIfHaC, ed. (2007). "Heavy menstrual bleeding". United Kingdom: National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence.

- Munro MG (2010). Abnormal Uterine Bleeding. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Munro MG; Critchley HO; Broder MS; Fraser IS (2011). "The FIGO Classification System ("PALM-COEIN") for causes of Abnormal Uterine Bleeding in Non-gravid Women in the Reproductive Years, Including Guidelines for Clinical Investigation". International Journal of Gynaecology and Obstetrics. 113 (1): 3–13. doi:10.1016/j.ijgo.2010.11.011. PMID 21345435.

- Wamsteker K; Emanuel MH; de Kruif JH (1993). "Transcervical hysteroscopic resection of submucous fibroids for abnormal uterine bleeding: results regarding the degree of intramural extension". Obstetrics and Gynecology. 82 (5). pp. 736–40.

- Munro MG; Heikinheimo O; Haththotuwa R; Tank JD; Fraser IS (2011). "The need for investigations to elucidate causes and effects of abnormal uterine bleeding". Seminars in Reproductive Medicine. 29 (5): 410–22. doi:10.1055/s-0031-1287665. PMID 22065327.