Falkland Islands

The Falkland Islands (/ˈfɔːlklənd/; Spanish: Islas Malvinas, pronounced [ˈislas malˈβinas]) is an archipelago in the South Atlantic Ocean on the Patagonian Shelf. The principal islands are about 300 miles (483 kilometres) east of South America's southern Patagonian coast and about 752 miles (1,210 kilometres) from the northern tip of the Antarctic Peninsula, at a latitude of about 52°S. The archipelago, with an area of 4,700 square miles (12,000 square kilometres), comprises East Falkland, West Falkland, and 776 smaller islands. As a British overseas territory, the Falklands have internal self-governance, and the United Kingdom takes responsibility for their defence and foreign affairs. The Falkland Islands' capital is Stanley on East Falkland.

Falkland Islands | |

|---|---|

| Motto: | |

| Anthem: "God Save the Queen" | |

| Unofficial anthem: "Song of the Falklands" | |

Location of the Falkland Islands | |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| First settlement | 1764 |

| British rule reasserted | 3 January 1833 |

| Falklands War | 2 April to 14 June 1982 |

| Current constitution | 1 January 2009 |

| Capital and largest settlement | Stanley 51°42′S 57°51′W |

| Official languages | English |

| Demonym(s) | Falkland Islander, Falklander |

| Government | Devolved parliamentary dependency under a constitutional monarchy |

• Monarch | Elizabeth II |

• Governor | Nigel Phillips |

| Barry Rowland | |

| Legislature | Legislative Assembly |

| Government of the United Kingdom | |

• Minister | Wendy Morton |

| Area | |

• Total | 12,200 km2 (4,700 sq mi) |

• Water (%) | 0 |

| Highest elevation | 2,313 ft (705 m) |

| Population | |

• 2016 census | 3,398[1] (not ranked) |

• Density | 0.28/km2 (0.7/sq mi) (not ranked) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2013 estimate |

• Total | $228.5 million[2] |

• Per capita | $96,962 (4th) |

| Gini (2010) | 34.17[3] medium · 64th |

| HDI (2010) | 0.874[4] very high · 20th |

| Currency | Falkland Islands pound (£) (FKP) |

| Time zone | UTC-03:00 (FKST) |

| Date format | dd/mm/yyyy |

| Driving side | left |

| Calling code | +500 |

| UK postcode | FIQQ 1ZZ |

| ISO 3166 code | FK |

| Internet TLD | .fk |

Controversy exists over the Falklands' discovery and subsequent colonisation by Europeans. At various times, the islands have had French, British, Spanish, and Argentine settlements. Britain reasserted its rule in 1833, but Argentina maintains its claim to the islands. In April 1982, Argentine military forces invaded the islands. British administration was restored two months later at the end of the Falklands War. Almost all Falklanders favour the archipelago remaining a UK overseas territory. Its sovereignty status is part of an ongoing dispute between Argentina and the United Kingdom.

The population (3,398 inhabitants in 2016)[1] consists primarily of native-born Falkland Islanders, the majority of British descent. Other ethnicities include French, Gibraltarian, and Scandinavian. Immigration from the United Kingdom, the South Atlantic island of Saint Helena, and Chile has reversed a population decline. The predominant (and official) language is English. Under the British Nationality (Falkland Islands) Act 1983, Falkland Islanders are British citizens.

The islands lie on the boundary of the subantarctic oceanic and tundra climate zones, and both major islands have mountain ranges reaching 2,300 feet (700 m). They are home to large bird populations, although many no longer breed on the main islands due to predation by introduced species. Major economic activities include fishing, tourism and sheep farming, with an emphasis on high-quality wool exports. Oil exploration, licensed by the Falkland Islands Government, remains controversial as a result of maritime disputes with Argentina.

Etymology

The name "Falkland Islands" comes from Falkland Sound, the strait that separates the two main islands.[5] The name "Falkland" was applied to the channel by John Strong, captain of an English expedition that landed on the islands in 1690. Strong named the strait in honour of Anthony Cary, 5th Viscount of Falkland, the Treasurer of the Navy who sponsored his journey.[6] The Viscount's title originates from the town of Falkland, Scotland—the town's name likely comes from a Gaelic term referring to an "enclosure" (lann),[upper-alpha 1] but it could less plausibly be from the Anglo-Saxon term "folkland" (land held by folk-right).[8] The name "Falklands" was not applied to the islands until 1765, when British captain John Byron of the Royal Navy claimed them for King George III as "Falkland's Islands".[9] The term "Falklands" is a standard abbreviation used to refer to the islands.

The Spanish name for the archipelago, Islas Malvinas, derives from the French Îles Malouines—the name given to the islands by French explorer Louis-Antoine de Bougainville in 1764.[10] Bougainville, who founded the islands' first settlement, named the area after the port of Saint-Malo (the point of departure for his ships and colonists).[11] The port, located in the Brittany region of western France, was named after St. Malo (or Maclou), the Christian evangelist who founded the city.[12]

At the twentieth session of the United Nations General Assembly, the Fourth Committee determined that, in all languages other than Spanish, all UN documentation would designate the territory as Falkland Islands (Malvinas). In Spanish, the territory was designated as Islas Malvinas (Falkland Islands).[13] The nomenclature used by the United Nations for statistical processing purposes is Falkland Islands (Malvinas).[14]

History

Although Fuegians from Patagonia may have visited the Falkland Islands in prehistoric times,[15] the islands were uninhabited when Europeans first discovered them.[16] Claims of discovery date back to the 16th century, but no consensus exists on whether early explorers discovered the Falklands or other islands in the South Atlantic.[17][18][upper-alpha 2] The first undisputed landing on the islands is attributed to English captain John Strong, who, en route to Peru and Chile's littoral in 1690, discovered the Falkland Sound and noted the islands' water and game.[20]

The Falklands remained uninhabited until the 1764 establishment of Port Louis on East Falkland by French captain Louis Antoine de Bougainville and the 1766 foundation of Port Egmont on Saunders Island by British captain John MacBride.[upper-alpha 3] Whether or not the settlements were aware of each other's existence is debated by historians.[23] In 1766, France surrendered its claim on the Falklands to Spain, which renamed the French colony Puerto Soledad the following year.[24] Problems began when Spain discovered and captured Port Egmont in 1770. War was narrowly avoided by its restitution to Britain in 1771.[25]

Both the British and Spanish settlements coexisted in the archipelago until 1774, when Britain's new economic and strategic considerations led it to voluntarily withdraw from the islands, leaving a plaque claiming the Falklands for King George III.[26] Spain's Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata became the only governmental presence in the territory. West Falkland was left abandoned, and Puerto Soledad became mostly a prison camp.[27] Amid the British invasions of the Río de la Plata during the Napoleonic Wars in Europe, the islands' governor evacuated the archipelago in 1806; Spain's remaining colonial garrison followed suit in 1811, except for gauchos and fishermen who remained voluntarily.[27]

Thereafter, the archipelago was visited only by fishing ships; its political status was undisputed until 1820, when Colonel David Jewett, an American privateer working for the United Provinces of the Río de la Plata, informed anchored ships about Buenos Aires' 1816 claim to Spain's territories in the South Atlantic.[28][upper-alpha 4] Since the islands had no permanent inhabitants, in 1823 Buenos Aires granted German-born merchant Luis Vernet permission to conduct fishing activities and exploit feral cattle in the archipelago.[upper-alpha 5] Vernet settled at the ruins of Puerto Soledad in 1826, and accumulated resources on the islands until the venture was secure enough to bring settlers and form a permanent colony.[32] Buenos Aires named Vernet military and civil commander of the islands in 1829,[33] and he attempted to regulate sealing to stop the activities of foreign whalers and sealers.[27] Vernet's venture lasted until a dispute over fishing and hunting rights led to a raid by the American warship USS Lexington in 1831,[34][upper-alpha 6] when United States Navy commander Silas Duncan declared the dissolution of the island's government.[35]

.png.webp)

Buenos Aires attempted to retain influence over the settlement by installing a garrison, but a mutiny in 1832 was followed the next year by the arrival of British forces who reasserted Britain's rule.[36] The Argentine Confederation (headed by Buenos Aires Governor Juan Manuel de Rosas) protested against Britain's actions,[37][upper-alpha 7] and Argentine governments have continued since then to register official protests against Britain.[40][upper-alpha 8] The British troops departed after completing their mission, leaving the area without formal government.[42] Vernet's deputy, the Scotsman Matthew Brisbane, returned to the islands that year to restore the business, but his efforts ended after, amid unrest at Port Louis, gaucho Antonio Rivero led a group of dissatisfied individuals to murder Brisbane and the settlement's senior leaders; survivors hid in a cave on a nearby island until the British returned and restored order.[42] In 1840, the Falklands became a Crown colony and Scottish settlers subsequently established an official pastoral community.[43] Four years later, nearly everyone relocated to Port Jackson, considered a better location for government, and merchant Samuel Lafone began a venture to encourage British colonisation.[44]

Stanley, as Port Jackson was soon renamed, officially became the seat of government in 1845.[45] Early in its history, Stanley had a negative reputation due to cargo-shipping losses; only in emergencies would ships rounding Cape Horn stop at the port.[46] Nevertheless, the Falklands' geographic location proved ideal for ship repairs and the "Wrecking Trade", the business of selling and buying shipwrecks and their cargoes.[47] Aside from this trade, commercial interest in the archipelago was minimal due to the low-value hides of the feral cattle roaming the pastures. Economic growth began only after the Falkland Islands Company, which bought out Lafone's failing enterprise in 1851,[upper-alpha 9] successfully introduced Cheviot sheep for wool farming, spurring other farms to follow suit.[49] The high cost of importing materials, combined with the shortage of labour and consequent high wages, meant the ship repair trade became uncompetitive. After 1870, it declined as the replacement of sail ships by steamships was accelerated by the low cost of coal in South America; by 1914, with the opening of the Panama Canal, the trade effectively ended.[50] In 1881, the Falkland Islands became financially independent of Britain.[45] For more than a century, the Falkland Islands Company dominated the trade and employment of the archipelago; in addition, it owned most housing in Stanley, which greatly benefited from the wool trade with the UK.[49]

.jpg.webp)

In the first half of the 20th century, the Falklands served an important role in Britain's territorial claims to subantarctic islands and a section of Antarctica. The Falklands governed these territories as the Falkland Islands Dependencies starting in 1908, and retained them until their dissolution in 1985.[51] The Falklands also played a minor role in the two world wars as a military base aiding control of the South Atlantic. In the First World War Battle of the Falkland Islands in December 1914, a Royal Navy fleet defeated an Imperial German squadron. In the Second World War, following the December 1939 Battle of the River Plate, the battle-damaged HMS Exeter steamed to the Falklands for repairs.[16] In 1942, a battalion en route to India was redeployed to the Falklands as a garrison amid fears of a Japanese seizure of the archipelago.[52] After the war ended, the Falklands economy was affected by declining wool prices and the political uncertainty resulting from the revived sovereignty dispute between the United Kingdom and Argentina.[46]

Simmering tensions between the UK and Argentina increased during the second half of the century, when Argentine President Juan Perón asserted sovereignty over the archipelago.[53] The sovereignty dispute intensified during the 1960s, shortly after the United Nations passed a resolution on decolonisation which Argentina interpreted as favourable to its position.[54] In 1965, the UN General Assembly passed Resolution 2065, calling for both states to conduct bilateral negotiations to reach a peaceful settlement of the dispute.[54] From 1966 until 1968, the UK confidentially discussed with Argentina the transfer of the Falklands, assuming its judgement would be accepted by the islanders.[55] An agreement on trade ties between the archipelago and the mainland was reached in 1971 and, consequently, Argentina built a temporary airfield at Stanley in 1972.[45] Nonetheless, Falklander dissent, as expressed by their strong lobby in the UK Parliament, and tensions between the UK and Argentina effectively limited sovereignty negotiations until 1977.[56]

Concerned at the expense of maintaining the Falkland Islands in an era of budget cuts, the UK again considered transferring sovereignty to Argentina in the early Thatcher government.[57] Substantive sovereignty talks again ended by 1981, and the dispute escalated with passing time.[58] In April 1982, the Falklands War began when Argentine military forces invaded the Falklands and other British territories in the South Atlantic, briefly occupying them until a UK expeditionary force retook the territories in June.[59] After the war, the United Kingdom expanded its military presence, building RAF Mount Pleasant and increasing the size of its garrison.[60] The war also left some 117 minefields containing nearly 20,000 mines of various types, including anti-vehicle and anti-personnel mines.[61] Due to the large number of deminer casualties, initial attempts to clear the mines ceased in 1983.[61][upper-alpha 10] Demining operations recommenced in 2009 and were completed in October 2020.[63]

Based on Lord Shackleton's recommendations, the Falklands diversified from a sheep-based monoculture into an economy of tourism and, with the establishment of the Falklands Exclusive Economic Zone, fisheries.[64][upper-alpha 11] The road network was also made more extensive, and the construction of RAF Mount Pleasant allowed access to long haul flights.[64] Oil exploration also began, with indications of possible commercially exploitable deposits in the Falklands basin.[65] Landmine clearance work restarted in 2009, in accordance with the UK's obligations under the Ottawa Treaty, and Sapper Hill Corral was cleared of mines in 2012, allowing access to an important historical landmark for the first time in 30 years.[66][67] Argentina and the UK re-established diplomatic relations in 1990; relations have since deteriorated as neither has agreed on the terms of future sovereignty discussions.[68] Disputes between the governments have led "some analysts [to] predict a growing conflict of interest between Argentina and Great Britain ... because of the recent expansion of the fishing industry in the waters surrounding the Falklands".[69]

Government

The Falkland Islands are a self-governing British Overseas Territory.[70] Under the 2009 Constitution, the islands have full internal self-government; the UK is responsible for foreign affairs, retaining the power "to protect UK interests and to ensure the overall good governance of the territory".[71] The Monarch of the United Kingdom is the head of state, and executive authority is exercised on the monarch's behalf by the governor, who appoints the islands' chief executive on the advice of members of the Legislative Assembly.[72] Both the governor and the chief executive serve as the head of government.[73]

Governor Nigel Phillips was appointed in September 2017[74] and Chief Executive Barry Rowland was appointed in October 2016.[75] The UK minister responsible for the Falkland Islands since 2019, Christopher Pincher, administers British foreign policy regarding the islands.[76]

The governor acts on the advice of the islands' Executive Council, composed of the chief executive, the Director of Finance and three elected members of the Legislative Assembly (with the governor as chairman).[72] The Legislative Assembly, a unicameral legislature, consists of the chief executive, the director of finance and eight members (five from Stanley and three from Camp) elected to four-year terms by universal suffrage.[72] All politicians in the Falkland Islands are independent; no political parties exist on the islands.[77] Since the 2013 general election, members of the Legislative Assembly have received a salary and are expected to work full-time and give up all previously held jobs or business interests.[78]

As a territory of the United Kingdom, the Falklands were part of the overseas countries and territories of the European Union until 2020.[79] The islands' judicial system, overseen by the Foreign and Commonwealth Office, is largely based on English law,[80] and the constitution binds the territory to the principles of the European Convention on Human Rights.[71] Residents have the right of appeal to the European Court of Human Rights and the Privy Council.[81][82] Law enforcement is the responsibility of the Royal Falkland Islands Police (RFIP),[80] and military defence of the islands is provided by the United Kingdom.[83] A British military garrison is stationed on the islands, and the Falkland Islands government funds an additional company-sized light infantry Falkland Islands Defence Force.[84] The Falklands claim an exclusive economic zone (EEZ) extending 200 nautical miles (370 km) from its coastal baselines, based on the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea; this zone overlaps with the EEZ of Argentina.[85]

Sovereignty dispute

The United Kingdom and Argentina both assert sovereignty over the Falkland Islands. The UK bases its position on its continuous administration of the islands since 1833 and the islanders' "right to self-determination as set out in the UN Charter".[86][87][88] Argentina claims that, when it achieved independence in 1816, it acquired the Falklands from Spain.[89][90][91] The incident of 1833 is particularly contentious; Argentina considers it proof of "Britain's usurpation" whereas the UK discounts it as a mere reassertion of its claim.[92][upper-alpha 12]

In 2009, the British prime minister, Gordon Brown, had a meeting with the Argentine president, Cristina Fernández de Kirchner, and said that there would be no further talks over the sovereignty of the Falklands.[95] In March 2013, the Falkland Islands held a referendum on its political status: 99.8% of votes cast favoured remaining a British overseas territory.[96][97] Argentina does not recognise the Falkland Islanders as a partner in negotiations.[89][98][99]

Geography

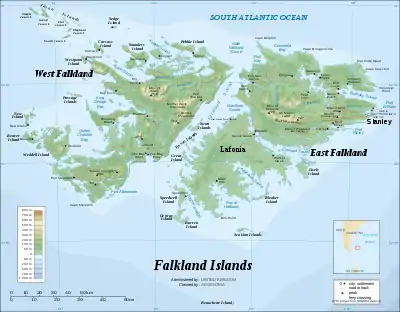

The Falkland Islands have a land area of 4,700 square miles (12,000 km2) and a coastline estimated at 800 miles (1,300 km).[100] The archipelago consists of two main islands, West Falkland and East Falkland, and 776 smaller islands.[101] The islands are predominantly mountainous and hilly,[102] with the major exception being the depressed plains of Lafonia (a peninsula forming the southern part of East Falkland).[103] The Falklands consists of continental crust fragments resulting from the break-up of Gondwana and the opening of the South Atlantic that began 130 million years ago. The islands are located in the South Atlantic Ocean, on the Patagonian Shelf, about 300 miles (480 km) east of Patagonia in southern Argentina.[104]

The Falklands' approximate location is latitude 51°40′ – 53°00′ S and longitude 57°40′ – 62°00′ W.[105] The archipelago's two main islands are separated by the Falkland Sound,[106] and its deep coastal indentations form natural harbours.[107] East Falkland houses Stanley (the capital and largest settlement),[105] the UK military base at RAF Mount Pleasant, and the archipelago's highest point: Mount Usborne, at 2,313 feet (705 m).[106] Outside of these significant settlements is the area colloquially known as "Camp", which is derived from the Spanish term for countryside (Campo).[108]

The climate of the islands is cold, windy and humid maritime.[104] Variability of daily weather is typical throughout the archipelago.[109] Rainfall is common over half of the year, averaging 610 millimetres (24 in) in Stanley, and sporadic light snowfall occurs nearly all year.[102] The temperature has historically stayed between 21.1 and −11.1 °C (70.0 and 12.0 °F) in Stanley, with mean monthly temperatures varying from 9 °C (48 °F) early in the year to −1 °C (30 °F) in July.[109] Strong westerly winds and cloudy skies are common.[102] Although numerous storms are recorded each month, conditions are normally calm.[109]

Biodiversity

The Falkland Islands are biogeographically part of the Antarctic zone,[110] with strong connections to the flora and fauna of Patagonia in mainland South America.[111] Land birds make up most of the Falklands' avifauna; 63 species breed on the islands, including 16 endemic species.[112] There is also abundant arthropod diversity on the islands.[113] The Falklands' flora consists of 163 native vascular species.[114] The islands' only native terrestrial mammal, the warrah, was hunted to extinction by European settlers.[115]

The islands are frequented by marine mammals, such as the southern elephant seal and the South American fur seal, and various types of cetaceans; offshore islands house the rare striated caracara. There are also five different penguin species and a few of the largest albatross colonies on the planet.[116] Endemic fish around the islands are primarily from the genus Galaxias.[113] The Falklands are treeless and have a wind-resistant vegetation predominantly composed of a variety of dwarf shrubs.[117]

Virtually the entire land area of the islands is used as pasture for sheep.[118] Introduced species include reindeer, hares, rabbits, Patagonian foxes, brown rats and cats.[119] Several of these species have harmed native flora and fauna, so the government has tried to contain, remove or exterminate foxes, rabbits and rats. Endemic land animals have been the most affected by introduced species, and several bird species have been extirpated from the larger islands.[120] The extent of human impact on the Falklands is unclear, since there is little long-term data on habitat change.[111]

Economy

The economy of the Falkland Islands is ranked the 222nd largest out of 229 in the world by GDP (PPP), but ranks 5th worldwide by GDP (PPP) per capita.[122] The unemployment rate was 1% in 2016, and inflation was calculated at 1.4% in 2014.[118] Based on 2010 data, the islands have a high Human Development Index of 0.874[4] and a moderate Gini coefficient for income inequality of 34.17.[3] The local currency is the Falkland Islands pound, which is pegged to the British pound sterling.[123]

Economic development was advanced by ship resupplying and sheep farming for high-quality wool.[124] The main sheep breeds in the Falkland Islands are Polwarth and Corriedale.[125] During the 1980s, although ranch under-investment and the use of synthetic fibres damaged the sheep-farming sector, the government secured a major revenue stream by the establishment of an exclusive economic zone and the sale of fishing licences to "anybody wishing to fish within this zone".[126] Since the end of the Falklands War in 1982, the islands' economic activity has increasingly focused on oil field exploration and tourism.[127]

The port settlement of Stanley has regained the islands' economic focus, with an increase in population as workers migrate from Camp.[128] Fear of dependence on fishing licences and threats from overfishing, illegal fishing and fish market price fluctuations have increased interest in oil drilling as an alternative source of revenue; exploration efforts have yet to find "exploitable reserves".[121] Development projects in education and sports have been funded by the Falklands government, without aid from the United Kingdom.[126]

The primary sector of the economy accounts for most of the Falkland Islands' gross domestic product, with the fishing industry alone contributing between 50% and 60% of annual GDP; agriculture also contributes significantly to GDP and employs about a tenth of the population.[129] A little over a quarter of the workforce serves the Falkland Islands government, making it the archipelago's largest employer.[130] Tourism, part of the service economy, has been spurred by increased interest in Antarctic exploration and the creation of direct air links with the United Kingdom and South America.[131] Tourists, mostly cruise ship passengers, are attracted by the archipelago's wildlife and environment, as well as activities such as fishing and wreck diving; the majority find accommodation in Stanley.[132] The islands' major exports include wool, hides, venison, fish and squid; its main imports include fuel, building materials and clothing.[118]

Demographics

The Falkland Islands population is homogeneous, mostly descended from Scottish and Welsh immigrants who settled in the territory after 1833.[133] The Falkland-born population are also descended from English and French people, Gibraltarians, Scandinavians and South Americans. The 2016 census indicated that 43% of residents were born on the archipelago, with foreign-born residents assimilated into local culture. The legal term for the right of residence is "belonging to the islands".[134][135] In 1983, full British citizenship was given to Falkland Islanders under the British Nationality (Falkland Islands) Act.[133]

A significant population decline affected the archipelago in the twentieth century, with many young islanders moving overseas in search of education, a modern lifestyle, and better job opportunities,[136] particularly to the British city of Southampton, which came to be known in the islands as "Stanley north".[137] In recent years, the islands' population decline has reduced, thanks to immigrants from the United Kingdom, Saint Helena, and Chile.[138] In the 2012 census, a majority of residents listed their nationality as Falkland Islander (59 percent), followed by British (29 percent), Saint Helenian (9.8 percent), and Chilean (5.4 percent).[139] A small number of Argentines also live on the islands.[140]

The Falkland Islands have a low population density.[141] According to the 2012 census, the average daily population of the Falklands was 2,932, excluding military personnel serving in the archipelago and their dependents.[upper-alpha 13] A 2012 report counted 1,300 uniformed personnel and 50 British Ministry of Defence civil servants present in the Falklands.[130] Stanley (with 2,121 residents) is the most-populous location on the archipelago, followed by Mount Pleasant (369 residents, primarily air-base contractors) and Camp (351 residents).[139] The islands' age distribution is skewed towards working age (20–60). Males outnumber females (53 to 47 percent), and this discrepancy is most prominent in the 20–60 age group.[134]

In the 2012 census, most islanders identified themselves as Christian (66 percent), followed by those with no religious affiliation (32 percent). The remaining 2 percent identified as adherents of other religions, including the Baháʼí Faith,[142] Buddhism,[143] and Islam.[144][139] The main Christian denominations are Anglicanism and other Protestantism, and Roman Catholicism.[145]

Education in the Falkland Islands, which follows England's system, is free and compulsory for residents aged between 5 and 16 years.[146] Primary education is available at Stanley, RAF Mount Pleasant (for children of service personnel) and a number of rural settlements. Secondary education is only available in Stanley, which offers boarding facilities and 12 subjects to General Certificate of Secondary Education (GCSE) level. Students aged 16 or older may study at colleges in England for their GCE Advanced Level or vocational qualifications. The Falkland Islands government pays for older students to attend institutions of higher education, usually in the United Kingdom.[146]

Culture

Falklands culture is based on the cultural traditions of its British settlers but has also been influenced by Hispanic South America.[138] Falklanders still use some terms and place names from the former Gaucho inhabitants.[147] The Falklands' predominant and official language is English, with the foremost dialect being British English; nonetheless, some inhabitants also speak Spanish.[138] According to naturalist Will Wagstaff, "the Falkland Islands are a very social place, and stopping for a chat is a way of life".[147]

The islands have two weekly newspapers: Teaberry Express and The Penguin News,[148] and television and radio broadcasts generally feature programming from the United Kingdom.[138] Wagstaff describes local cuisine as "very British in character with much use made of the homegrown vegetables, local lamb, mutton, beef, and fish". Common between meals are "home made cakes and biscuits with tea or coffee".[149] Social activities are, according to Wagstaff, "typical of that of a small British town with a variety of clubs and organisations covering many aspects of community life".[150]

See also

Notes

- According to researcher Simon Taylor, the exact Gaelic etymology is unclear as the "falk" in the name could have stood for "hidden" (falach), "wash" (failc), or "heavy rain" (falc).[7]

- Based on his analysis of Falkland Islands discovery claims, historian John Dunmore concludes that "[a] number of countries could therefore lay some claim to the archipelago under the heading of first discoverers: Spain, Holland, Britain, and even Italy and Portugal – although the last two claimants might be stretching things a little."[19]

- In 1764, Bougainville claimed the islands in the name of Louis XV of France. In 1765, British captain John Byron claimed the islands in the name of George III of Great Britain.[21][22]

- According to Argentine legal analyst Roberto Laver, the United Kingdom disregards Jewett's actions because the government he represented "was not recognized either by Britain or any other foreign power at the time" and "no act of occupation followed the ceremony of claiming possession".[29]

- Before leaving for the Falklands Vernet stamped his grant at the British Consulate, repeating this when Buenos Aires extended his grant in 1828.[30] The cordial relationship between the consulate and Vernet led him to express "the wish that, in the event of the British returning to the islands, HMG would take his settlement under their protection".[31]

- The log of the "Lexington" only reports the destruction of arms and a powder store, but Vernet made a claim for compensation from the US Government stating that the entire settlement was destroyed.[34]

- As discussed by Roberto Laver, not only did Rosas not break relations with Britain because of the "essential" nature of "British economic support", but he offered the Falklands "as a bargaining chip ... in exchange for the cancellation of Argentina's million-pound debt with the British bank of Baring Brothers".[38] In 1850, Rosas' government ratified the Arana–Southern Treaty, which put "an end to the existing differences, and of restoring perfect relations of friendship" between the United Kingdom and Argentina.[39]

- Argentina protested in 1841, 1849, 1884, 1888, 1908, 1927 and 1933, and has made annual protests to the United Nations since 1946.[41]

- There were continual tensions with the colonial administration over Lafone's failure to establish any permanent settlers, and over the price of beef supplied to the settlement. Moreover, although his concession required Lafone to bring settlers from the United Kingdom, most of the settlers he brought were gauchos from Uruguay.[48]

- The minefields were fenced off and marked; there remain unexploded ordnance and improvised explosive devices.[61] Detection and clearance of mines in the Falklands has proven difficult as some were air-delivered and not in marked fields; approximately 80% lie in sand or peat, where the position of mines can shift, making removal procedures difficult.[62]

- In 1976, Lord Shackleton produced a report into the economic future of the islands; however, his recommendations were not implemented because Britain sought to avoid confronting Argentina over sovereignty.[64] Lord Shackleton was once again tasked, in 1982, to produce a report into the economic development of the islands. His new report criticised the large farming companies, and recommended transferring ownership of farms from absentee landlords to local landowners. Shackleton also suggested diversifying the economy into fishing, oil exploration, and tourism; moreover, he recommended the establishment of a road network, and conservation measures to preserve the islands' natural resources.[64]

- Argentina considers that, in 1833, the UK established an "illegal occupation" of the Falklands after expelling Argentine authorities and settlers from the islands with a threat of "greater force" and, afterwards, barring Argentines from resettling the islands.[89][90][91] The Falkland Islands' government considers that only Argentina's military personnel was expelled in 1833, but its civilian settlers were "invited to stay" and did so except for 2 and their wives.[93] International affairs scholar Lowell Gustafson considers that "[t]he use of force by the British on the Falkland Islands in 1833 was less dramatic than later Argentine rhetoric has suggested".[94]

- At the time of the 2012 census, 91 Falklands residents were overseas.[139]

References

- "2016 Census Report". Policy and Economic Development Unit, Falkland Islands Government. 2017. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 January 2018.

- "State of the Falkland Islands Economy" (PDF). March 2015. Retrieved 8 January 2017.

- Avakov 2013, p. 54.

- Avakov 2013, p. 47.

- Jones 2009, p. 73.

- See:

- Dotan 2010, p. 165,

- Room 2006, p. 129.

- Taylor & Márkus 2005, p. 158.

- Room 2006, p. 129.

- See:

- Paine 2000, p. 45,

- Room 2006, p. 129.

- Hince 2001, p. 121.

- See:

- Hince 2001, p. 121,

- Room 2006, p. 129.

- Balmaceda 2011, Chapter 36.

- Foreign Office 1961, p. 80.

- "Standard Country and Area Codes Classifications". United Nations Statistics Division. 13 February 2013. Retrieved 3 July 2013.

- G. Hattersley-Smith (June 1983). "Fuegian Indians in the Falkland Islands". Polar Record. Cambridge University Press. 21 (135): 605–06. doi:10.1017/S003224740002204X.

- Carafano 2005, p. 367.

- White, Michael (2 February 2012). "Who first owned the Falkland Islands?". The Guardian. Retrieved 3 July 2013.

- Goebel 1971, pp. xiv–xv.

- Dunmore 2005, p. 93.

- See:

- Gustafson 1988, p. 5,

- Headland 1989, p. 66,

- Heawood 2011, p. 182.

- Gustafson 1988, pp. 9–10.

- Dunmore 2005, pp. 139–40.

- See:

- Goebel 1971, pp. 226, 232, 269,

- Gustafson 1988, pp. 9–10.

- Segal 1991, p. 240.

- Gibran 1998, p. 26.

- Gibran 1998, pp. 26–27.

- Gibran 1998, p. 27.

- See:

- Gibran 1998, p. 27,

- Marley 2008, p. 714.

- Laver 2001, p. 73.

- Cawkell 2001, pp. 48–50.

- Cawkell 2001, p. 50.

- See:

- Gibran 1998, pp. 27–28,

- Sicker 2002, p. 32.

- Pascoe & Pepper 2008, pp. 540–46.

- Pascoe & Pepper 2008, pp. 541–44.

- Peterson 1964, p. 106.

- Graham-Yooll 2002, p. 50.

- Reginald & Elliot 1983, pp. 25–26.

- Laver 2001, pp. 122–23.

- Hertslet 1851, p. 105.

- Gustafson 1988, pp. 34–35.

- Gustafson 1988, p. 34.

- Graham-Yooll 2002, pp. 51–52.

- Aldrich & Connell 1998, p. 201.

- See:

- Bernhardson 2011, Stanley and Vicinity: History,

- Reginald & Elliot 1983, pp. 9, 27.

- Reginald & Elliot 1983, p. 9.

- Bernhardson 2011, Stanley and Vicinity: History.

- Strange 1987, pp. 72–74.

- Strange 1987, p. 84.

- See:

- Bernhardson 2011, Stanley and Vicinity: History,

- Reginald & Elliot 1983, p. 9.

- Strange 1987, pp. 72–73.

- Day 2013, p. 129–30.

- Haddelsey & Carroll 2014, Prologue.

- Zepeda 2005, p. 102.

- Laver 2001, p. 125.

- Thomas 1991, p. 24.

- Thomas 1991, pp. 24–27.

- Norton-Taylor, Richard; Evans, Rob (28 June 2005). "UK held secret talks to cede sovereignty: Minister met junta envoy in Switzerland, official war history reveals". The Guardian. Retrieved 12 June 2014.

- Thomas 1991, pp. 28–31.

- See:

- Reginald & Elliot 1983, pp. 5, 10–12, 67,

- Zepeda 2005, pp. 102–03.

- Gibran 1998, pp. 130–35.

- "The Long Road to Clearing Falklands Landmines". BBC News. 14 March 2010. Retrieved 29 June 2014.

- Ruan, Juan Carlos; Macheme, Jill E. (August 2001). "Landmines in the Sand: The Falkland Islands". The Journal of ERW and Mine Action. James Madison University. 5 (2). ISSN 1533-6905. Retrieved 29 June 2014.

- "Falklands community invited to 'Reclaim the Beach' to celebrate completion of demining – Penguin News". Penguin News. 23 October 2020. Retrieved 23 October 2020.

- Cawkell 2001, p. 147.

- "Falklands Drilling Will Resume in Second Quarter of 2015, Announced Premier Oil". MercoPress. 15 May 2014. Retrieved 29 June 2014.

- "The Falkland Islands, 30 Years After the War with Argentina". Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 29 June 2014.

- Grant Munro (8 December 2011). "Falklands' Land Mine Clearance Set to Enter a New Expanded Phase in Early 2012". MercoPress. Retrieved 29 June 2014.

- See:

- Lansford 2012, p. 1528,

- Zepeda 2005, pp. 102–03.

- Zepeda 2005, p. 103.

- Cahill 2010, "Falkland Islands".

- "New Year begins with a new Constitution for the Falklands". MercoPress. 1 January 2009. Retrieved 9 July 2013.

- "The Falkland Islands Constitution Order 2008" (PDF). The Queen in Council. 5 November 2008. Retrieved 9 July 2013.

- Buckman 2012, p. 394.

- "Falklands' Swearing in Ceremony for Governor Phillips on 12 September". MercoPress. 2 September 2017. Retrieved 12 September 2017.

- "Falklands' new Chief Executive has 30 years experience in England's public sector". MercoPress. 13 October 2016. Retrieved 20 October 2016.

- "Minister of State at the Foreign & Commonwealth Office". United Kingdom Government. 27 June 2014. Retrieved 2 July 2014.

- Central Intelligence Agency 2011, "Falkland Islands (Malvinas) – Government".

- "Falklands lawmakers: "The full time problem"". MercoPress. 28 October 2013. Retrieved 1 July 2014.

- EuropeAid (4 June 2014). "EU relations with Overseas Countries and Territories". European Commission. Archived from the original on 1 July 2014. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- Sainato 2010, pp. 157–158.

- "A New Approach to the British Overseas Territories" (PDF). London: Ministry of Justice. 2012. p. 4. Retrieved 25 August 2013.

- "The Falkland Islands (Appeals to Privy Council) (Amendment) Order 2009", legislation.gov.uk, The National Archives, SI 2006/3205

- Central Intelligence Agency 2011, "Falkland Islands (Malvinas) – Transportation".

- Martin Fletcher (6 March 2010). "Falklands Defence Force better equipped than ever, says commanding officer". The Times. Retrieved 18 March 2011.

- International Boundaries Research Unit. "Argentina and UK claims to maritime jurisdiction in the South Atlantic and Southern Oceans". Durham University. Retrieved 26 June 2014.

- Lansford 2012, p. 1528.

- Watt, Nicholas (27 March 2009). "Falkland Islands sovereignty talks out of the question, says Gordon Brown". The Guardian. Retrieved 24 August 2013.

- "Supporting the Falkland Islanders' right to self-determination". Policy. United Kingdom Foreign & Commonwealth Office and Ministry of Defence. 12 March 2013. Retrieved 29 May 2014.

- Secretaría de Relaciones Exteriores. "La Cuestión de las Islas Malvinas" (in Spanish). Ministerio de Relaciones Exteriores y Culto (República Argentina). Retrieved 10 October 2013.

- Michael Reisman (January 1983). "The Struggle for The Falklands". Yale Law Journal. Faculty Scholarship Series. 93 (287): 306. Retrieved 23 October 2013.

- "Decolonization Committee Says Argentina, United Kingdom Should Renew Efforts on Falkland Islands (Malvinas) Question". Press Release. United Nations. 18 June 2004. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- Gustafson 1988, pp. 26–27.

- "Relationship with Argentina". Self-Governance. Falkland Island Government. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- Gustafson 1988, p. 26.

- "No talks on Falklands, says Brown". BBC News. 28 March 2009. Retrieved 24 August 2013.

- "Falklands referendum: Islanders vote on British status". BBC News. 10 March 2013. Retrieved 24 August 2013.

- Brindicci, Marcos; Bustamante, Juan (12 March 2013). "Falkland Islanders vote overwhelmingly to keep British rule". Reuters. Retrieved 24 August 2013.

- "Timerman rejects meeting Falklands representatives; only interested in 'bilateral round' with Hague". MercoPress. 31 January 2013. Retrieved 26 January 2014.

- Laura Smith-Spark (11 March 2013). "Falkland Islands hold referendum on disputed status". CNN. Retrieved 26 January 2014.

- See:

- Guo 2007, p. 112,

- Sainato 2010, p. 157.

- Sainato 2010, p. 157.

- Central Intelligence Agency 2011, "Falkland Islands (Malvinas) – Geography".

- Trewby 2002, p. 79.

- Klügel 2009, p. 66.

- Guo 2007, p. 112.

- Hemmerle 2005, p. 318.

- See:

- Blouet & Blouet 2009, p. 100,

- Central Intelligence Agency 2011, "Falkland Islands (Malvinas) – Geography"

- Hince 2001, "Camp".

- Gibran 1998, p. 16.

- Jónsdóttir 2007, pp. 84–86.

- Helen Otley; Grant Munro; Andrea Clausen; Becky Ingham (May 2008). "Falkland Islands State of the Environment Report 2008" (PDF). Environmental Planning Department Falkland Islands Government. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 July 2011. Retrieved 25 March 2011.

- Clark & Dingwall 1985, p. 131.

- Clark & Dingwall 1985, p. 132.

- Clark & Dingwall 1985, p. 129.

- Hince 2001, p. 370.

- Chura, Lindsay R. (30 June 2015). "Pan-American Scientific Delegation Visit to the Falkland Islands". Science and Diplomacy.

The ocean’s fecundity also draws globally important seabird populations to the archipelago; the Falkland Islands host some of the world’s largest albatross colonies and five penguin species.

- Jónsdóttir 2007, p. 85.

- "Falkland Islands (Islas Malvinas)". Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 10 July 2013.

- Bell 2007, p. 544.

- Bell 2007, pp. 542–545.

- Royle 2001, p. 171.

- The World Factbook — Central Intelligence Agency. Cia.gov. Retrieved on 20 September 2017.

- "Regions and territories: Falkland Islands". BBC News. 12 June 2012. Retrieved 26 June 2014.

- See:

- Calvert 2004, p. 134,

- Royle 2001, p. 170.

- "Agriculture". Falkland Islands Government. Retrieved 13 February 2016.

- Royle 2001, p. 170.

- Hemmerle 2005, p. 319.

- Royle 2001, pp. 170–171.

- "The Economy". Falkland Islands Government. Retrieved 26 June 2014.

- "The Falkland Islands: Everything You Ever Wanted to Know in Data and Charts". The Guardian. 3 January 2013. Retrieved 12 June 2014.

- See:

- Bertram, Muir & Stonehouse 2007, p. 144,

- Prideaux 2008, p. 171.

- See:

- Prideaux 2008, p. 171,

- Royle 2006, p. 183.

- Laver 2001, p. 9.

- "Falkland Islands Census Statistics, 2006" (PDF). Falkland Islands Government. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 December 2010. Retrieved 4 June 2010.

- Falkland Islands Government. "Falkland Islands Census 2016" (PDF). Falkland Islands Government. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 March 2018. Retrieved 6 May 2018.

- See:

- Gibran 1998, p. 18,

- Laver 2001, p. 173.

- Falklands still home to optimists as invasion anniversary nears, The Guardian, Andy Beckett, 19 March 2012

- Minahan 2013, p. 139.

- "Falkland Islands Census 2012: Headline results" (PDF). Falkland Islands Government. 10 September 2012. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 May 2013. Retrieved 19 December 2012.

- "Falklands Referendum: Voters from many countries around the world voted Yes". MercoPress. 28 June 2013. Retrieved 22 July 2013.

- Royle 2006, p. 181.

- "The Largest Baha'i (sic) Communities (mid-2000)". Adherents.com. September 2001. Archived from the original on 20 October 2001. Retrieved 11 October 2020.

- "Falkland Islands Census Statistics 2006" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 December 2010.

- "The world in muslim populations, every country listed". The Guardian. 8 October 2009. Retrieved 2 March 2019.

- Religions of the World: A Comprehensive Encyclopedia of Beliefs and Practices, 2nd Edition [6 volumes] by J. Gordon Melton, Martin Baumann, ABC-CLIO, p. 1093.

- "Education". Falkland Islands Government. Archived from the original on 26 October 2018. Retrieved 29 May 2014.

- Wagstaff 2001, p. 21.

- Wagstaff 2001, p. 66.

- Wagstaff 2001, pp. 63–64.

- Wagstaff 2001, p. 65.

Bibliography

- Aldrich, Robert; Connell, John (1998). The Last Colonies. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-41461-6.

- Avakov, Alexander (2013). Quality of Life, Balance of Powers, and Nuclear Weapons. New York: Algora Publishing. ISBN 978-0-87586-963-6.

- Balmaceda, Daniel (2011). Historias Inesperadas de la Historia Argentina (in Spanish). Buenos Aires: Editorial Sudamericana. ISBN 978-950-07-3390-8.

- Bell, Brian (2007). "Introduced Species". In Beau Riffenburgh (ed.). Encyclopedia of the Antarctic. 1. New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-97024-2.

- Bernhardson, Wayne (2011). Patagonia: Including the Falkland Islands. Altona, Manitoba: Friesens. ISBN 978-1-59880-965-7.

- Bertram, Esther; Muir, Shona; Stonehouse, Bernard (2007). "Gateway Ports in the Development of Antarctic Tourism". Prospects for Polar Tourism. Oxon, England: CAB International. ISBN 978-1-84593-247-3.

- Blouet, Brian; Blouet, Olwyn (2009). Latin America and the Caribbean. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley and Sons. ISBN 978-0-470-38773-3.

- Buckman, Robert (2012). Latin America 2012. Ranson, West Virginia: Stryker-Post Publications. ISBN 978-1-61048-887-7.

- Cahill, Kevin (2010). Who Owns the World: The Surprising Truth About Every Piece of Land on the Planet. New York: Grand Central Publishing. ISBN 978-0-446-55139-7.

- Calvert, Peter (2004). A Political and Economic Dictionary of Latin America. London: Europa Publications. ISBN 978-0-203-40378-5.

- Carafano, James Jay (2005). "Falkland/Malvinas Islands". In Will Kaufman; Heidi Slettedahl Macpherson (eds.). Britain and the Americas: Culture, Politics, and History. Santa Barbara, California: ABC–CLIO. ISBN 978-1-85109-431-8.

- Cawkell, Mary (2001). The History of the Falkland Islands. Oswestry, England: Anthony Nelson Ltd. ISBN 978-0-904614-55-8.

- Central Intelligence Agency (2011). The CIA World Factbook 2012. New York: Skyhorse Publishing, Inc. ISBN 978-1-61608-332-8.

- Clark, Malcolm; Dingwall, Paul (1985). Conservation of Islands in the Southern Ocean. Cambridge, England: IUCN. ISBN 978-2-88032-503-9.

- Day, David (2013). Antarctica: A Biography (Reprint ed.). Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-967055-0.

- Dotan, Yossi (2010). Watercraft on World Coins: America and Asia, 1800–2008. 2. Portland, Oregon: The Alpha Press. ISBN 978-1-898595-50-2.

- Dunmore, John (2005). Storms and Dreams. Auckland, New Zealand: Exisle Publishing Limited. ISBN 978-0-908988-57-0.

- Foreign Office (1961). Report on the Proceedings of the General Assembly of the United Nations. London: H.M. Stationery Office.

- Gibran, Daniel (1998). The Falklands War: Britain Versus the Past in the South Atlantic. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc. ISBN 978-0-7864-0406-3.

- Goebel, Julius (1971). The Struggle for the Falkland Islands: A Study in Legal and Diplomatic History. Port Washington, New York: Kennikat Press. ISBN 978-0-8046-1390-3.

- Graham-Yooll, Andrew (2002). Imperial Skirmishes: War and Gunboat Diplomacy in Latin America. Oxford, England: Signal Books Limited. ISBN 978-1-902669-21-2.

- Guo, Rongxing (2007). Territorial Disputes and Resource Management. New York: Nova Science Publishers, Inc. ISBN 978-1-60021-445-5.

- Gustafson, Lowell (1988). The Sovereignty Dispute Over the Falkland (Malvinas) Islands. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-504184-2.

- Haddelsey, Stephen; Carroll, Alan (2014). Operation Tabarin: Britain's Secret Wartime Expedition to Antarctica 1944–46. Stroud, England: The History Press. ISBN 978-0-7509-5511-9.

- Headland, Robert (1989). Chronological List of Antarctic Expeditions and Related Historical Events. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-30903-5.

- Heawood, Edward (2011). F. H. H. Guillemard (ed.). A History of Geographical Discovery in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries (Reprint ed.). New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-60049-2.

- Hemmerle, Oliver Benjamin (2005). "Falkland Islands". In R. W. McColl (ed.). Encyclopedia of World Geography. 1. New York: Golson Books, Ltd. ISBN 978-0-8160-5786-3.

- Hertslet, Lewis (1851). A Complete Collection of the Treaties and Conventions, and Reciprocal Regulations, At Present Subsisting Between Great Britain and Foreign Powers, and of the Laws, Decrees, and Orders in Council, Concerning the Same. 8. London: Harrison and Son.

- Hince, Bernadette (2001). The Antarctic Dictionary. Collingwood, Melbourne: CSIRO Publishing. ISBN 978-0-9577471-1-1.

- Jones, Roger (2009). What's Who? A Dictionary of Things Named After People and the People They are Named After. Leicester, England: Matador. ISBN 978-1-84876-047-9.

- Jónsdóttir, Ingibjörg (2007). "Botany during the Swedish Antarctic Expedition 1901–1903". In Jorge Rabassa; Maria Laura Borla (eds.). Antarctic Peninsula and Tierra del Fuego. Leiden, Netherlands: Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-0-415-41379-4.

- Klügel, Andreas (2009). "Atlantic Region". In Rosemary Gillespie; David Clague (eds.). Encyclopedia of Islands. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-25649-1.

- Lansford, Tom (2012). Thomas Muller; Judith Isacoff; Tom Lansford (eds.). Political Handbook of the World 2012. Los Angeles, California: CQ Press. ISBN 978-1-60871-995-2.

- Laver, Roberto (2001). The Falklands/Malvinas Case. The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. ISBN 978-90-411-1534-8.

- Marley, David (2008). Wars of the Americas (2nd ed.). Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-59884-100-8.

- Minahan, James (2013). Ethnic Groups of the Americas. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-61069-163-5.

- Paine, Lincoln (2000). Ships of Discovery and Exploration. New York: Mariner Books. ISBN 978-0-395-98415-4.

- Pascoe, Graham; Pepper, Peter (2008). "Luis Vernet". In David Tatham (ed.). The Dictionary of Falklands Biography (Including South Georgia): From Discovery Up to 1981. Ledbury, England: David Tatham. ISBN 978-0-9558985-0-1.

- Peterson, Harold (1964). Argentina and the United States 1810–1960. New York: University Publishers Inc. ISBN 978-0-87395-010-7.

- Prideaux, Bruce (2008). "Falkland Islands". In Michael Lück (ed.). The Encyclopedia of Tourism and Recreation in Marine Environments. Oxon, England: CAB International. ISBN 978-1-84593-350-0.

- Reginald, Robert; Elliot, Jeffrey (1983). Tempest in a Teapot: The Falkland Islands War. Wheeling, Illinois: Whitehall Co. ISBN 978-0-89370-267-0.

- Room, Adrian (2006). Placenames of the World (2nd ed.). Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc. ISBN 978-0-7864-2248-7.

- Royle, Stephen (2001). A Geography of Islands: Small Island Insularity. New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-203-16036-7.

- Royle, Stephen (2006). "The Falkland Islands". In Godfrey Baldacchino (ed.). Extreme Tourism: Lessons from the World's Cold Water Islands. Amsterdam: Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-08-044656-1.

- Sainato, Vincenzo (2010). "Falkland Islands". In Graeme Newman; Janet Stamatel; Hang-en Sung (eds.). Crime and Punishment around the World. 2. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-0-313-35133-4.

- Segal, Gerald (1991). The World Affairs Companion. New York: Simon & Schuster/Touchstone. ISBN 978-0-671-74157-0.

- Sicker, Martin (2002). The Geopolitics of Security in the Americas. Westport, Connecticut: Praeger Publishers. ISBN 978-0-275-97255-4.

- Strange, Ian (1987). The Falkland Islands and Their Natural History. Newton Abbot, England: David & Charles. ISBN 978-0-7153-8833-4.

- Taylor, Simon; Márkus, Gilbert (2005). The Place-Names of Fife: Central Fife between the Rivers Leven and Eden. Donington, England: Shaun Tyas. ISBN 978-1900289-93-1.

- Thomas, David (1991). "The View from Whitehall". In Wayne Smith (ed.). Toward Resolution? The Falklands/Malvinas Dispute. Boulder, Colorado: Lynne Rienner Publishers. ISBN 978-1-55587-265-6.

- Trewby, Mary (2002). Antarctica: An Encyclopedia from Abbott Ice Shelf to Zooplankton. Richmond Hill, Ontario: Firefly Books. ISBN 978-1-55297-590-9.

- Wagstaff, William (2001). Falkland Islands: The Bradt Travel Guide. Buckinghamshire, England: Bradt Travel Guides, Ltd. ISBN 978-1-84162-037-4.

- Zepeda, Alexis (2005). "Argentina". In Will Kaufman; Heidi Slettedahl Macpherson (eds.). Britain and the Americas: Culture, Politics, and History. Santa Barbara, California: ABC–CLIO. ISBN 978-1-85109-431-8.

Further reading

- Caviedes, César (1994). "Conflict Over The Falkland Islands: A Never-Ending Story?". Latin American Research Review. 29 (2): 172–187. Archived from the original on 18 January 2012.

- Darwin, Charles (1846). "On the Geology of the Falkland Islands" (PDF). Quarterly Journal of the Geological Society. 2 (1–2): 267–274. doi:10.1144/GSL.JGS.1846.002.01-02.46. S2CID 129936121. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 July 2014. Retrieved 9 March 2013.

- Escudé, Carlos; Cisneros, Andrés, eds. (2000). Historia de las Relaciones Exteriores Argentinas. Buenos Aires, Argentina: GEL/Nuevohacer. ISBN 978-950-694-546-6. Work developed and published under the auspices of the Argentine Council for International Relations (CARI).

- Freedman, Lawrence (2005). The Official History of the Falklands Campaign. Oxon, UK: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-7146-5207-8.

- Michael Frenchman (28 November 1980). "Britain puts forward four options on Falklands (Nick Ridley visit & leaseback)". The Times. p. 7. Retrieved 5 July 2020.

- Greig, D. W. (1983). "Sovereignty and the Falkland Islands Crisis" (PDF). Australian Year Book of International Law. 8: 20–70. doi:10.1163/26660229-008-01-900000006. ISSN 0084-7658.

- Ivanov, L. L.; et al. (2003). . Sofia, Bulgaria: Manfred Wörner Foundation. ISBN 978-954-91503-1-5. Printed in Bulgaria by Double T Publishers.

External links

Wikimedia Atlas of Falkland Islands

Wikimedia Atlas of Falkland Islands- Falkland Islands Government (official site)

- Falkland Islands Development Corporation (official site)

- Falkland Islands News Network (official site)

- Falkland Islands Profile (BBC)

- . Encyclopædia Britannica. 10 (11th ed.). 1911.

.svg.png.webp)

Countries.png.webp)