Ferdinand Domela Nieuwenhuis

Ferdinand Jacobus Domela Nieuwenhuis (31 December 1846 – 18 November 1919) was a Dutch socialist politician and later a social anarchist and anti-militarist. He was a Lutheran preacher who, after he lost his faith, started a political fight for workers. He was a founder of the Dutch socialist movement and the first socialist in the Dutch parliament.

Ferdinand Domela Nieuwenhuis | |

|---|---|

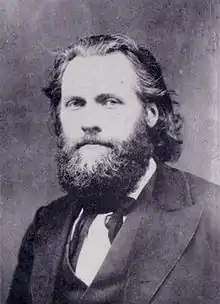

Ferdinand Domela Nieuwenhuis (c. 1875) | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | December 31, 1846 Amsterdam, North Holland, |

| Died | November 18, 1919 (aged 72) Hilversum, North Holland, |

| Political party | Social Democratic League (1881-1897) |

Biography

Early life

Ferdinand Domela Nieuwenhuis was born in Amsterdam, the son of Ferdinand Jacob Domela Nieuwenhuis, Lutheran pastor and professor of theology, and Henriette Frances Berry. When Nieuwenhuis was ten years old, his mother died. His brother was art collector Adriaan Jacob Domela Nieuwenhuis. His family added the second surname "Domela" in 1859.[1] After his theological studies, he became an Evangelical Lutheran preacher and served in various Dutch towns. He gradually lost his faith and came into contact with the social issues of the time.

Pastor

In 1870 Domela Nieuwenhuis was appointed pastor in Harlingen. There he founded a division of the Peace League because of the Franco-Prussian War. The same year, he married Johanna Lulofs (1847-1872) with whom he had two sons, though she died in childbirth. In 1872 he wrote two articles in De Gids about the peace movement. He supported the workers who asked for a raise. Subsequently he worked as a minister in Beverwijk and The Hague, but with increasing reluctance. In 1874, he married Johanna Adriana Verhagen (1842-1877) with whom he had two daughters and a son who died very young. He went to Germany in 1875 to study the social problem and was interested in social work. While serving as a minister, he had come into contact with social problems through the conversations he had with members of his congregation. The death of his second wife in childbirth led him to increasingly doubt the existence of an almighty God. The work of liberal theologians such as Ernest Renan and David Friedrich Strauss strengthened his doubts. Nieuwenhuis eventually lost his faith in a personal God, becoming a pantheist and later an atheist. On September 1, 1879, he resigned his position as preacher in The Hague, becoming active in various socialist activities.

Speaker and socialist

A legacy in 1879 gave him financial independence. Some opponents would use this against him a few years later, counting him among the capitalists.[2] He acquired much theoretical knowledge through the ideas of Proudhon, Marx and Engels. He converted to socialism and remarried in 1880 to Johanna Frederika Schingen Hagen (1843-1884) with whom he had a son, but she also died in childbirth. He went into the countryside for lectures on the social issue and delivered one of his first speeches at the Algemeen Nederlandsch Werklieden Verbond. After the lecture, he met with the chairman, Willem Ansing, who convinced him to become a member. In his lectures he 'preached' against the five K's: Kerk, Koning, Kapitaal, Kazerne and Kroeg. He also worked as an editor at the socialist magazine Recht voor Allen, a magazine he co-founded. He became a member of the Freethinkers' Association De Dageraad. In 1879 he gave a lecture to the Social Democratic Association. After the Social Democratic Associations merged into the Social Democratic League (Dutch: Sociaal-Democratische Bond, SDB) in 1881, they elected Domela Nieuwenhuis as secretary. He argued for equal rights for men and women, teetotalism and the introduction of universal suffrage, and supported socialist workers' initiatives such as strikes.

Although mediocre as a writer, Domela Nieuwenhuis was an fascinating and engaging speaker.[3] He made a great impression on the agricultural workers and farmers in Friesland and Groningen. He was often compared to Jesus, the Frisian agricultural workers even called him "our savior". Domela himself stimulated that image. The growth of hair and beard made him appear prophetic, and he laced his talks with biblical images, in order to appeal to his audience.

Electoral Union

Domela Nieuwenhuis co-founded the Union for General Electoral and Voting Rights in 1882, often referred to as the Electoral Union for convenience. The Electoral Union was a partnership of socialist and social-liberal advocates of universal suffrage. At the time, only 1/8th of adult men were allowed to vote. In 1883, a major demonstration for universal suffrage was held by the Electoral Union on Budget Day. The demonstrators lined the route of the Royal procession and dropped a large number of ribbons with protest slogans on the carriage at one place.

On September 15, 1884, Domela Nieuwenhuis, together with other representatives of the Electoral Union, presented a petition to Prime Minister Jan Heemskerk. The prime minister rejected the petition's demand for universal suffrage. Under pressure from the electoral rights movement, the right to vote was expanded in 1887, allowing about 1/7th of adult men to vote. The largest demonstration in the history of the Electoral Union was organized on Budget Day of 1885. Another petition was drawn up and handed over to the government.

Convicted

On April 24, 1886, the critical article "De koning komt" was published in Recht voor Allen. In this article, Willem III was described as “someone who makes so little of his job.”[4] Although he was not the author of the article, Domela Nieuwenhuis did take final responsibility for the article as editor-in-chief. The inclusion of ten blank pages depicting the activities of the King was also completely wrong. He received many statements of support; the liberal Sam van Houten acted as his lawyer (and unsuccessfully litigated up to the Supreme Court). Domela had to go to Utrecht prison for a year in 1887 for lese majesty. At the time, care was taken to treat political prisoners differently from non-political prisoners. People talked about compulsory prison labor as sticking bags, Domela Nieuwenhuis did slightly better boxes folding. On his early resignation, when he was pardoned after seven months, he received a worn suit from the director as a gift. He then took up residence in the Malaccahofje in The Hague.

Political career

In 1888, the Frisian People's Party (FVP) put forward Nieuwenhuis as a candidate for the general election in the Frisian constituency of Schoterland. The FVP was a partnership of the Frisian departments of the Electoral Union and the SDB, and had about 5000 members. Domela Nieuwenhuis obtained 31.6% of the constituency vote, this was more than the Anti-Revolutionary candidate, and so he got through to the second round. His opponent was Bernardus Hermanus Heldt, chairman of the Algemeen Nederlandsch Werklieden Verbond and candidate on behalf of the liberal electoral association. The elections of that year were dominated by the opposition of liberals and (for the first time) cooperating confessionals. In the heat of the battle, the reformed daily newspaper De Standaard, through their foreman Abraham Kuyper, invited the voters in Schoterland to vote for the liberal and thus Domela Nieuwenhuis came completely unexpectedly into parliament.

He was elected to the House of Representatives, one of the two chambers that make up the Dutch parliament. He was the first and, at the time, the only socialist elected into parliament. On May 14, 1888, Domela Nieuwenhuis gave his first parliamentary speech, in which he argued for a ban on forced shopping. Forced shopkeeping means that employees are forced by their employer to buy their necessary items only in a specific shop. The employees would be fired if they refused to buy from their boss's shop alone. Prices in these stores were very high. The government refused to do anything about forced shopping.

Because he was able to formulate all kinds of things well and write them down in Recht voor Allen, socialism gained in popularity in the country. He attended congresses of the Second International, where, among other things, he argued for a general strike at the outbreak of war. He also remarried to Johanna Egberta Godthelp (1863-1933) with whom he had a daughter and two sons, including the painter César Domela.

In 1891 he reluctantly stood for re-election. Just before the elections of 1891, Domela Nieuwenhuis wrote the brochure Four Years of Class Reign or What Could Have Been Done with Universal Suffrage, which was distributed in hundreds of thousands of copies. In this brochure he gave a list of proposals he had made and which had been rejected. According to Domela Nieuwenhuis, these proposals would have been adopted in the case of universal suffrage. A few examples are: ban on forced shopping; introduction of the eight-hour working day; introduction of the minimum wage; work ban for children under the age of fifteen; free education; setting up sickness funds and pension funds; benefit for industrial accidents; reduction of indirect taxes; ending the Aceh war; independence for the colonies; nationalization of the railways and the abolition of tolls on national roads.[5] Ferdinand Domela Nieuwenhuis lost the elections of 1891. The liberal lawyer Treub was willing to give up his seat to him, but Domela Nieuwenhuis did not want to take his place to a liberal and refused.

Nieuwenhuis moved more and more toward anarchist beliefs. The SDB followed him there but was not free of trouble. Many did not agree with this shift, most importantly Pieter Jelles Troelstra, who left the party together with some other prominent members and started the Sociaal Democratische Arbeiders Partij (SDAP) in 1894, a more reformist party. In the same year, the SDB was declared illegal. Nieuwenhuis remained hostile to Troelstra and his SDAP.

The historian Jan Willem Stutje argues that Domela Nieuwenhuis also used anti-semitic characterizations in his polemics, especially in his conflict with Pieter Jelles Troelstra, who, in contrast to Domela, was a parliamentarian. Troelstra had a certain following among the Jewish diamond workers, according to Stutje this gave Domela cause for anti-semitic statements. After Troelstra seceded from the Social Democratic Union in 1894, and the break had thus become a fact, this subsided and there were only occasional anti-semitic regurgitations.[6][7]

Anarchism

At the conferences of the Second International (IAA) in 1891 and 1893, anarchists, including Nieuwenhuis, presented resolutions for a call for general conscientious objection and for a general strike in the event of a declaration of war. The majority of the IAA, however, believed that all wars would disappear if capitalism could be removed.

Domela Nieuwenhuis was increasingly attracted to anarchism and revolution. Initially the SDB supported him in this; the Congress of 1892 even passed a resolution that "lasting improvement for the proletariat on the basis of modern society is not possible". The goal became "revolution and overthrow of the existing social order by all legal and illegal means". The latter led to the banning of the SDB as an association, after which the union split into the SDAP and the Socialistenbond in 1894. Domela Nieuwenhuis became a member of the latter, but soon their goals did not go far enough for him and in 1898 he terminated his membership.

He turned away from parliamentary democracy and became an anarchist. After 1898 Domela devoted a lot of time to his editorial work for De Vrije Socialist. In 1903 he moved to Het Gooi and devoted himself to his publicist work. He wrote many historical books, including several biographies. In 1903 he made the first Dutch translation of Utopia, Thomas More's story about an ideal society on a socialist basis. In 1904 he co-founded the International Antimilitarist Association (IAMV) together with Nico Schermerhorn. In 1910 he published his memoirs Van Christen tot Anarchist.

Later life

Nieuwenhuis kept publishing and fighting for the social-anarchistic cause. He visited various congresses, started and joined new movements and did not shy away from action.

After he died in Hilversum at the age of 72 on 18 November 1919, he was one of the first to be cremated and interred at Westerveld in Velsen. His funeral procession, attended by 12,000 sympathizers, traveled through Amsterdam.[8] In 1931 his statue, made by Johan Polet, was unveiled in Amsterdam. It is located on Nassauplein, in Amsterdam-West, next to Westerpark. Nearby is also the Domela Nieuwenhuisplantsoen named after him. On October 28, 2014, the square in Hilversum where he lived, was renamed Domela Nieuwenhuisplein. The house is a municipal monument.[9]

He was popular in the Netherlands for his performances at strikes by craftsmen, but also among peat workers. A photo of him could be found in many workers' houses. Because he stood up for the Frisian peat workers in his life, he was nicknamed Us Ferlosser. The Domela Nieuwenhuis Museum is located in Heerenveen, part of the Museum Willem van Haren.

References

- Parlement.com

- Maas en Scheldebode, 9 september 1886, geraadpleegd via International institute of social history, ARCH00483.774

- Levend Verleden, H.P.H. Jansen, 1983 Sijthoff Amsterdam - ISBN 90 218 2673 9

- Jan Meyer: Domela : een hemel op aarde : leven en streven van Ferdinand Domela Nieuwenhuis; 1993; blz. 130.

- Jan Meyer: Domela : een hemel op aarde : leven en streven van Ferdinand Domela Nieuwenhuis; 1993;

- Jan Willem Stutje: "Antisemitisme onder Nederlandse socialisten in het fin de siècle", Low Countries Historical Review, Volume 129-3 (2014), pp. 4-26

- Jan Willem Stutje: "Ferdinand Domela Nieuwenhuis: een romantisch revolutionair."

- NRC, 22 november 1919, avondblad

- https://web.archive.org/web/20140809212154/http://hilversum.geotalk.nl/info.php?monumentid=583

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ferdinand Domela Nieuwenhuis. |

- Works by Ferdinand Domela Nieuwenhuis at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Ferdinand Domela Nieuwenhuis at Internet Archive

- Works by Ferdinand Domela Nieuwenhuis at Marxists Internet Archive

- (in Dutch) Ferdinand Domela Nieuwenhuis in Biografisch Woordenboek van het Socialisme en de Arbeidersbeweging in Nederland (BWSA)

- Wolfram Beyer: The flaw in the peoples‘ army, in: Peace News No 2447, London June–August 2002 (Kontroverse Karl Liebknecht / Domela Nieuwenhuis), online