Ferris Barracks

Ferris Barracks is a former US military garrison located in Erlangen, a Middle Franconian (German: Mittelfranken) city in Bavaria (German: Bayern), Germany. It was active as a US military base between 1945 and 1994. The facility was occupied after World War II and designated Ferris Barracks in honor of Second Lieutenant (2LT) Geoffrey Cheney Ferris. Ferris Barracks was closed on 28 June, 1994, and officially turned over to the German government. Though largely dismantled, certain historic buildings and monuments have been preserved and converted for alternative use. The area has undergone extensive construction and is now referred to as Röthelheimpark.

| Ferris Barracks Erlangen, Germany | |

|---|---|

Ferris Barracks Ferris Barracks (Germany) | |

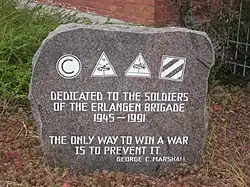

Ferris Barracks Memorial to the Soldiers of the Erlangen Brigade from 1945-1991. | |

| Coordinates | 49°35′29.8″N 011°01′40.8″E |

| Type | Military Garrison |

| Site information | |

| Condition | Closed |

| Site history | |

| In use | 1890-1994 |

| Garrison information | |

| Occupants | |

History

Early Use

Until the 18th century, soldiers stationed in Erlangen were quartered by private citizens. After its transition to the Kingdom of Bavaria in 1810, Erlangen tried several times to become a garrison town. Beginning in 1868, several small kaserne (English: barracks) were established. In 1890, the 19th Royal Bavarian Infantry Regiment (German: Königlich Bayerisches 19. Infantrie Regiment), part of the III Royal Bavarian Corps (German: III. Königlich Bayerisches Armee-Korps), was permanently stationed in Erlangen. To accommodate regimental units, a drill area of 150 hectares (370 acres) was purchased and set aside as an Exerzierplatz (English: drill area), and construction began on a new infantry kaserne along Luitpoldstraße (present day Drausnickstraße), to the north of the drill area. In 1893, a hospital was established for the garrison in the northwest corner of the drill area. In 1901, the 10th Royal Bavarian Artillery Regiment (German: Königlich Bayerisches 10. Feldartillerie-Regiment) was relocated to a new kaserne built on the northern edge of the drill area. This new kaserne was called simply Artillerie-Kaserne (English: Artillery Barracks). Through 1904, additional buildings were erected on the artillery kaserne including staff buildings, guard houses, a stockade, hay-, straw- and oats-magazines, wagon houses, a scale, stables and other workshops. In 1912 the Offizierspeiseanstalt (English: Officer's Mess), also called the Kasino, was built. During World War I, both regiments fought on the front lines. The drill area was used as a Prisoner of War (POW) camp during the war. In 1915, the number of Russian, French and Italian prisoners interned there was approximately 3,600.

Weimar Republic

With the armistice on November 11, 1918, most soldiers were discharged and were released into private life. After the war, Erlangen retained its status as a garrison town, however due to restrictions imposed by the Treaty of Versailles, only select smaller training units remained at the garrison. The original infantry barracks fell into disuse by the military and control of that facility reverted to the city. It was later used to house refugees. Beginning in 1923, the garrison hospital was converted to a skin clinic used by the Friedrich-Alexander University.

On 1 October, 1922, a monument was erected in front of the Kasino, named Gefallenendenkmal für das 10. Feldartillerie-Regiment (English: Memorial to the Fallen of the 10th Field Artillery Regiment).

World War II

The reintroduction of conscription in 1935 and subsequent rearmament led to a massive expansion of military facilities in Erlangen. On 16 March, 1935, construction began on a second artillery kaserne located on the northeast corner of the drill area to the east and adjacent to the original Artilleriekaserne. On 1 October, 1935, two batteries from the 17th Artillery Regiment occupied the new artillery kaserne. In 1936, the Wehrmacht (English: defense forces) took control of these facilities.

In 1938, a new panzer (English: tank) kaserne complex was constructed on the drill area south of the original garrison hospital along Hartmannstraße. Originally called Panzerkaserne, it was occupied by the 25th Panzer Regiment, along with regimental and department staff, and included a new hospital. It was later renamed Villers-Brettoneux-Kaserne,[1] after the Second Battle of Villers-Bretoneux in the first world war, which saw the first use of German tanks in battle. The two artillery kaserne were also renamed. The original artillery kaserne, which had been home to the 10th Field Artillery Regiment was renamed St. Mihiel-Kaserne, after the town of St. Mihiel, France, where the 10th Field Artillery fought for nearly two years during the first world war. The new artillery kaserne was named Rheinland Kaserne,[2] in honor of the remilitarization of the Rheinland in March of 1936 by the German Army. In total, approximately 48 buildings and structures were erected on the drill square between 1935 and 1938. The outbreak of the second world war brought construction on these sites to a standstill.

The Villers-Bretonneux-Kaserne was home to the Panther tank training center from 1943, due to its proximity to the tank's manufacturer, Maschinenfabrik Augsburg-Nürnberg AG (MAN), in Nuernberg, and to the Grafenwoehr training area.[3] Most Panther officers, drivers, driving instructors and repair technicians of the Wehrmacht and Waffen-SS were trained in Erlangen at the Panzer-Ersatz und Ausbildungs-Abteilung 25 (English: Tank Replacement and Training Unit 25).[4] Buildings on the St. Mihiel-Kaserne were used to quarter soldiers and units undergoing Panther tank training.[5]

At the close of World War II, the defense of Erlangen fell under the military authority of Oberstleutnant (English: Lieutenant-Colonel) Werner Lorleberg,[6] a pastor's son[7] and professional soldier. After many exchanges, the Oberbürgermeister (English: Lord Mayor) of Erlangen, Dr. Herbert Ohly, convinced Lorleberg that Adolf Hitler's order to fight on at all costs was pointless.[8] On 16 April, 1945, Ohly and Lorleberg offered to hand over the city of Erlangen to the 1st Battalion, 7th Infantry Regiment, 3rd Infantry Division, 7th US Army without a fight. Lorleberg explained that there were approximately 120 soldiers in the Thalermühle mill complex who refused to surrender. The US colonel rejected the offer to surrender and gave Lorleberg until 2:00 PM to convince these soldiers to surrender peacefully, or he would fire on the city. Lorleberg, along with police lieutenant Andreas Fischer and their driver, Thomas Pfannenmüller, went by car under a white flag to the Thalermühle mill complex in the Regnitzwiesen. The driver remained with the vehicle while Lorleberg and Fischer went inside the Firma Mobius to order the soldiers to surrender. Lorleberg did not managed to convince the soldiers to surrender, and he was killed, whether by suicide or by a disgruntled soldier, as he walked out of the building. The police officer, who waited in front of the building, heard a single shot as Lorleberg was approaching the exit. A memorial was erected in 1955 near the place where he fell. In his honor, Kaiser Wilhelm Platz in Erlangen was renamed to Lorlebergplatz on November 1, 1945.[9][10] The city of Erlangen was spared further destruction, and US forces soon occupied what then became known as Ferris Barracks; bounded on the west by Hartmannstraße, on the north by Artilleriestraße, on the east by present day Kurt-Schumacherstraße and on the south by present day Staudtstraße.

2LT Geoffrey C. Ferris

Geoffrey Cheney Ferris was born on 8 April, 1918, in New Haven, Connecticut. He was the youngest of four children born to Walter Lewis Ferris and Alice Josephine Cheney. Next to his photograph in his high school yearbook is printed "None but himself can be his parallel".[11] Prior to joining the Army, Ferris joined the Connecticut National Guard as a private on 19 September, 1940. He was commissioned as a second lieutenant on 24 February, 1941, holding that grade until his separation on 4 December, 1941. Ferris enlisted in the Army as a private on 23 January, 1942, at Hartford, Connecticut.[12] After Officer Candidate School Class 23-42 at Fort Sill, Oklahoma, he was commissioned as a second lieutenant and served as an artillery observer assigned to the 6th Battalion, 33rd Field Artillery Regiment, 1st Infantry Division. On the morning of 6 May, 1943, Lieutenant Ferris reported to Company E, 26th Infantry Regiment. Seeing that it was impossible to secure a suitable observation post in the area occupied by Company E, Lieutenant Ferris, carrying a field phone and wire reel, advanced several hundred yards beyond the front lines before being mortally wounded by enemy fire. He died the next day. Initially interred in Tunisia, he was re-interred at the Long Island National Cemetery in New York. Lieutenant Ferris was posthumously awarded the Silver Star[13]and the Distinguished Service Cross[14] for his actions. The citation for his award reads:

The President of the United States of America, authorized by Act of Congress, July 9, 1918, takes pride in presenting the Distinguished Service Cross (Posthumously) to Second Lieutenant (Field Artillery) Geoffrey C. Ferris (ASN: 0-420345), United States Army, for extraordinary heroism in connection with military operations against an armed enemy while serving with the 6th Battalion, 33d Field Artillery Regiment, 1st Infantry Division, in action against enemy forces on 6 May 1943, near Beja, Tunisia.

On the morning of 6 May 1943, the 33d Artillery Regiment was given the mission of taking Hill 139 in the vicinity of Beja, Tunisia. Because of the heavy machine gun and mortar fire covering all approaches, it was necessary to attack before daylight. Second Lieutenant Ferris, as artillery forward observer with the assault elements, crawled forward across open terrain swept by withering enemy machine gun fire to a point well beyond our lines.

Realizing the danger of his mission, he had ordered his men to remain behind while he advanced with a wire reel and telephone until he was killed. The unselfish heroism and the courage and zeal with which Second Lieutenant Ferris performed this deed exemplify the highest traditions of the military forces of the United States and reflect great credit upon himself, the 1st Infantry Division, and the United States Army.

General Orders: Headquarters, U.S. Army-North African Theater of Operations, General Orders No. 47 (July 6, 1943).

DSC Award

DSC Award Silver Star Award

Silver Star Award

Ferris Barracks was named in his honor and he was further honored in the Congressional Record on 17 June, 2003,[15] during a ceremony dedicating the Headquarters Building, 1st Battalion, 33rd Field Artillery Regiment in Bamberg, Germany in his name. Soldiers who undergo Basic Training at Fort Sill, Oklahoma, are eligible for the Geoffrey C. Ferris Award upon graduation. It is given for “unwavering dedication to the mission and perseverance in the face of adversity, emulating the highest ideals of bravery and heroism.”

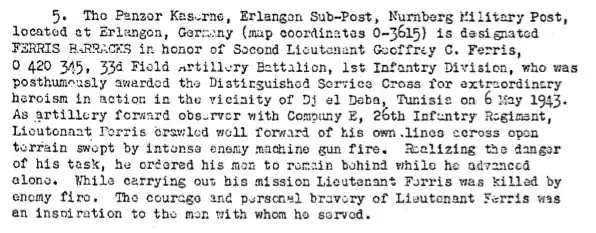

Naming

The facility was officially designated Ferris Barracks in honor of Second Lieutenant (2LT) Geoffery C. Ferris on 11 May, 1949, by General Lucius D. Clay, then head of the European Command. The facility may have been known informally as Ferris Barracks before that date; purportedly named by General George S. Patton upon his arrival in Erlangen on 22 April, 1945.[16]

Closure

Ferris Barracks was selected for closure as part of the general drawdown of forces in Germany at the end of the Cold War. A ceremony was held on 16 September, 1993, marking the departure of the 2nd Brigade, 3rd Infantry Division from Ferris Barracks. At the beginning of the drawdown there were approximately 3,500 soldiers stationed there. On 28 June, 1994, Ferris Barracks was closed and officially handed over to the German Government. The city of Erlangen acquired the former installation. Older structures from the original Artillerie-Kaserne as well as monuments were protected under the Denkmalschutz (English: monument protection), with most modern buildings being demolished. Historic buildings have been refurbished and converted for alternative use such as businesses, restaurants, shopping and university buildings.

See also

References

- Weihsmann, Helmut (1998). Bauen unterm Hakenkreuz: Architektur des Untergangs. Austria: Promedia. p. 391. ISBN 3853711138.

- Weihsmann, Helmut (1998). Bauen unterm Hakenkreuz: Architektur des Untergangs. Austria: Promedia. p. 391. ISBN 3853711138.

- Forczyk, Robert (2016). Tank Warfare on the Eastern Front 1943-1945: Red Steamroller. Barnsley: Pen & Sword Aviation. p. 16. ISBN 978 1 78346 278 0.

- Kurowski, Franz (2010). Panzer Aces III: German Tank Commanders in Combat in World War II. Mechanicsburg: Stackpole Books. p. 48. ISBN 978-0-8117-0654-4.

- Gregory, Don; Gehlen, William (2009). Two Soldiers, Two Lost Fronts: German War Diaries of the Stalingrad and North Africa Campaigns. Drexel Hill: Casemate. p. 87. ISBN 978-1-935149-05-7.

- Fouse, Gary C. (2005). Erlangen: An American's History of a German Town. Lanham: University Press of America. p. 222. ISBN 0-7618-3024-3.

- Schubert, Albin (1985). Das Ende des Zweiten Weltkrieges im Coburger Land: Mit einem Rückblick auf die Vorgeschichte des Krieges (German ed.). Riemann. p. 280. ISBN 978-3980000192.

- Hansen, Randall (2014). Disobeying Hitler: German Resistance After Valkyrie. Oxford: University Press. p. 430. ISBN 978-0-19-992792-0.

- Taegert, Jürgen-Joachim; Schmidt, Hugo Karl (2016). In Ängsten – und siehe, wirleben. Norderstedt: Books-On-Demand. p. 226. ISBN 97837 3923896 8.

- Wilkes, Johannes (2014). Stadtgespräche aus Erlangen. Gmeiner-Verlag. ISBN 9783839216323.

- The Roxbury School (Cheshire, CT) (1936). The Rolling Stone. Cheshire: Students of The Roxbury School. p. 28.

- "World War II Army Enlistment Records". archives.gov. 1942-01-23. Retrieved 2017-10-31.

- "Army Awards of the Silver Star for Conspicuous Gallantry in Action During World War II". Retrieved 2017-10-31.

- Anon (2014). To Bizerte With The II Corps - 23 April - 13 May 1943. Lucknow Books. p. Annex No. 2. ASIN B06XGHBJPQ.

- Congressional Record, V. 149, Pt. 11, June 20, 2003 to June 19, 2003. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office. 2003.

- Sprouse, Joseph (2010). Documentary: Gen. George Patton, Jr. , 2nd Lt. Peter Bonano, and A Vanishing Cache of Nazi Gold. Indianapolis: Dog Ear Publishing. p. 66. ISBN 9781608447466.