Franconia

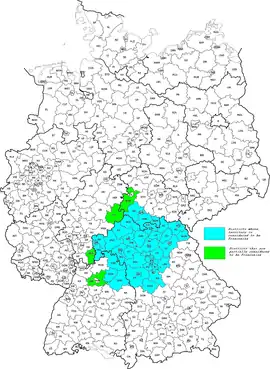

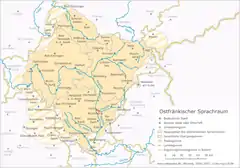

Franconia (German: Franken; in the Franconian dialect: Franggn [frɑŋgŋ̩]) is a region in Germany, characterised by its culture and language, and may be roughly associated with the areas in which the East Franconian dialect group, colloquially referred to as "Franconian" (German: "Fränkisch"), is spoken.[1] There are several other Franconian dialects, but only the East Franconian ones are colloquially referred to as "Franconian".

Franconia

Franken | |

|---|---|

Cultural region of Germany | |

| Anthem: "Frankenlied" | |

| |

| Country | |

| Largest cities | 1. Nuremberg 2. Würzburg 3. Fürth 4. Erlangen 5. Bamberg |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

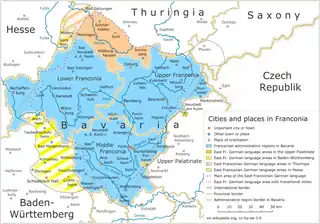

"Core Franconia" is constituted by the three administrative regions of Lower, Middle, and Upper Franconia (largest cities: Nuremberg, Würzburg, and Bamberg, respectively) of the state of Bavaria. Also part of the cultural region of Franconia are the adjacent Franconian-speaking regions of the otherwise Thuringian and Upper Saxon-speaking state of Thuringia (South Thuringia, south of the Rennsteig ridge; largest city: Suhl), the Franconian-speaking parts of Heilbronn-Franconia (largest city: Schwäbisch Hall) in the state of Baden-Württemberg, and small parts of the state of Hesse.

Those parts of the region of Vogtland lying in the state of Saxony (largest city: Plauen) are sometimes regarded as Franconian as well, because the Vogtlandian dialects are mostly East Franconian. The inhabitants of Saxon Vogtland, however, mostly do not consider themselves as "Franconian". On the other hand, the inhabitants of the Hessian-speaking parts of Lower Franconia west of the Spessart mountains (largest city: Aschaffenburg) do consider themselves as "Franconian". Heilbronn-Franconia's largest city of Heilbronn and its surrounding areas being South Franconian-speaking, those are only sometimes regarded as Franconian.

Franconia's largest city and unofficial capital is Nuremberg, which is contiguous with Erlangen and Fürth, with which it forms a large conurbation, with around 1.3 million inhabitants.

The German word Franken—Franconians—also refers to the ethnic group, which is mainly to be found in this region. They are to be distinguished from the Germanic tribe of the Franks, and historically formed their easternmost settlement area. The origins of Franconia lie in the settlement of the Franks from the 6th century in the area probably populated until then mainly by the Elbe Germanic people in the Main river area, known from the 9th century as East Francia (Francia Orientalis).[2] In the Middle Ages the region formed much of the eastern part of the Duchy of Franconia and, from 1500, the Franconian Circle.[3] During the course of restructuring the south German states by Napoleon, after the demise of the Holy Roman Empire, most of Franconia was awarded to Bavaria.[4]

Etymology

The German name for Franconia, Franken, comes from the dative plural form of Franke, a member of the Germanic tribe known as the Franks.[5] The name of the Franks in turn derives from a word meaning "daring, bold", cognate with old Norwegian frakkr, "quick, bold".[6] Franks from the Middle and Lower Rhine gradually gained control of (and so gave their name to) what is now Franconia during the 6th to 8th centuries.[7] English distinguishes between Franks (the early medieval Germanic people) and Franconians in reference to the high medieval stem duchy, following Middle Latin use of Francia for France vs. Franconia for the German duchy. In German the name Franken is equally used for both, while the French are called Franzosen, after Old French françois, from Latin franciscus, from Late Latin Francus, from Frank, the Germanic tribe.

Geography

Overview

The Franconian lands lie principally in Bavaria, north and south of the sinuous River Main which, together with the left (southern) Regnitz tributary, including its Rednitz and Pegnitz headstreams, drains most of Franconia. Other large rivers include the upper Werra in Thuringia and the Tauber, as well as the upper Jagst and Kocher streams in the west, both right tributaries of the Neckar. In southern Middle Franconia, the Altmühl flows towards the Danube; the Rhine–Main–Danube Canal crosses the European Watershed. The man-made Franconian Lake District has become a popular destination for day-trippers and tourists.

The landscape is characterized by numerous Mittelgebirge ranges of the German Central Uplands. The Western natural border of Franconia is formed by the Spessart and Rhön Mountains, separating it from the former Rhenish Franconian lands around Aschaffenburg (officially part of Lower Franconia), whose inhabitants speak Hessian dialects. To the north rise the Rennsteig ridge of the Thuringian Forest, the Thuringian Highland and the Franconian Forest, the border with the Upper Saxon lands of Thuringia. The Franconian lands include the present-day South Thuringian districts of Schmalkalden-Meiningen, Hildburghausen and Sonneberg, the historical Gau of Grabfeld, held by the House of Henneberg from the 11th century and later part of the Wettin duchy of Saxe-Meiningen.

In the east, the Fichtel Mountains lead to Vogtland, Bohemian Egerland (Chebsko) in the Czech Republic, and the Bavarian Upper Palatinate. The hills of the Franconian Jura in the south mark the border with the Upper Bavarian region (Altbayern), historical Swabia, and the Danube basin. The northern parts of the Upper Bavarian Eichstätt District, territory of the historical Bishopric of Eichstätt, are also counted as part of Franconia.

In the west, Franconia proper comprises the Tauber Franconia region along the Tauber river, which As of 2014 is largely part of the Main-Tauber-Kreis in Baden-Württemberg. The state's larger Heilbronn-Franken region also includes the adjacent Hohenlohe and Schwäbisch Hall districts. In the city of Heilbronn, beyond the Haller Ebene plateau, South Franconian dialects are spoken. Furthermore, in those easternmost parts of the Neckar-Odenwald-Kreis which had formerly belonged to the Bishopric of Würzburg, the inhabitants have preserved their Franconian identity. Franconian areas in East Hesse along Spessart and Rhön comprise Gersfeld and Ehrenberg.

The two largest cities of Franconia are Nuremberg and Würzburg. Though located on the southeastern periphery of the area, the Nuremberg metropolitan area is often identified as the economic and cultural centre of Franconia. Further cities in Bavarian Franconia include Fürth, Erlangen, Bayreuth, Bamberg, Aschaffenburg, Schweinfurt, Hof, Coburg, Ansbach and Schwabach. The major (East) Franconian towns in Baden-Württemberg are Schwäbisch Hall on the Kocher — the imperial city declared itself "Swabian" in 1442 — and Crailsheim on the Jagst river. The main towns in Thuringia are Suhl and Meiningen.

Rothenburg is one of the best known towns in Franconia

Rothenburg is one of the best known towns in Franconia Walberla in Franconia

Walberla in Franconia Water wheel at the Regnitz

Water wheel at the Regnitz Nuremberg is the largest city of Franconia

Nuremberg is the largest city of Franconia Aerial view of the Veste Coburg

Aerial view of the Veste Coburg

Extent

Here: the vestry of Meiningen's municipal church in South Thuringia. The Franconian Rake may be seen on the left

Franconia may be distinguished from the regions that surround it by its peculiar historical factors and its cultural and especially linguistic characteristics, but it is not a political entity with a fixed or tightly defined area. As a result, it is debated whether some areas belong to Franconia or not. Pointers to a more precise definition of Franconia's boundaries include: the territories covered by the former Duchy of Franconia and former Franconian Circle,[8] the range of the East Franconian dialect group, the common culture and history of the region and the use of the Franconian Rake on coats of arms, flags and seals. However, a sense of popular consciousness of being Franconian is only detectable from the 19th century onwards, which is why the circumstances of the emergence of a Frankish identity are disputed.[9] Franconia has many cultural peculiarities which have been adopted from other regions and further developed.[9]

The following regions are counted as part of Franconia today: the Bavarian provinces of Lower Franconia, Upper Franconia and Middle Franconia, the municipality of Pyrbaum in the county of Neumarkt in der Oberpfalz, the northwestern part of the Upper Bavarian county of Eichstätt (covering the same area as the old county of Alt-Eichstätt), the East Franconian counties of South Thuringia, parts of Fulda and the Odenwaldkreis in Hesse, the Baden-Württemberg regions of Tauber Franconia and Hohenlohe as well as the region around the Badenian Buchen.

In individual cases the membership of some areas is disputed. These include the Bavarian language area of Alt-Eichstätt[9] and the Hessian-speaking[10] region around Aschaffenburg, which was never part of the Franconian Imperial Circle. The affiliation of the city of Heilbronn, whose inhabitants do not call themselves Franks,[11] is also controversial. Moreover, the sense of belonging to Franconia in the Frankish-speaking areas of Upper Palatinate, South Thuringia[12] and Hesse is sometimes less marked.

Administrative divisions

The region of Franconia is divided among the states of Hesse, Thuringia, Bavaria and Baden-Württemberg. The largest part of Franconia, both by population and area, belongs to the Free State of Bavaria and is divided into the three provinces (Regierungsbezirke) of Middle Franconia (capital: Ansbach), Upper Franconia (capital: Bayreuth) and Lower Franconia (capital: Würzburg). The name of these provinces, as in the case of Upper and Lower Bavaria, refers to their situation with respect to the River Main. Thus Upper Franconia lies on the upper reaches of the river, Lower Franconia on its lower reaches and Middle Franconia lies in between, although the Main itself does not flow through Middle Franconia. Where the boundaries of these three provinces meet (the 'tripoint') is the Dreifrankenstein ("Three Franconias Rock").[13] Small parts of Franconia also belong to the Bavarian provinces of Upper Palatinate and Upper Bavaria.

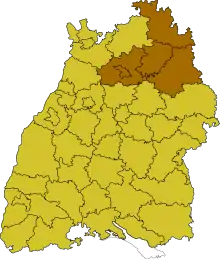

The Franconian territories of Baden-Württemberg are the regions of Tauber Franconia and Hohenlohe (which belong to the Heilbronn-Franconia Region with its office in Heilbronn and form part of the Stuttgart Region) and the area around the Badenian Buchen in the Rhein-Neckar Region.

The Franconian parts of Thuringia (Henneberg Franconia) lie within the Southwest Thuringia Planning Region.

The Franconian regions in Hesse form the smaller parts of the counties of Fulda (Kassel province) and the Odenwaldkreis (Darmstadt province), or lie on the borders with Bavaria or Thuringia.

Rivers and lakes

The two most important rivers of the region are the Main and its primary tributary, the Regnitz. The tributaries of these two rivers in Franconia are the Tauber, Pegnitz, Rednitz and Franconian Saale. Other major rivers in the region are the Jagst and Kocher in Hohenlohe-Franconia, which empty into the Neckar north of Heilbronn in Baden-Württemberg, the Altmühl and the Wörnitz in Middle Franconia, both tributaries of the Danube, and the upper and middle reaches of the Werra, the right-hand headstream of the Weser. In the northeast of Upper Franconia rise two left-hand tributaries of the Elbe: the Saxon Saale and the Eger.

The Main-Danube Canal connects the Main and Danube across Franconia, running from Bamberg via Nuremberg to Kelheim. It thus complements the Rhine, Main and Danube, helping to ensure a continuous navigable waterway between the North Sea and the Black Sea. In Franconia, there are only a few, often very small, natural lakes. This is due to fact that most natural lakes in Germany are glacial or volcanic in origin, and Franconia escaped both influences in recent earth history. Among the largest waterbodies are reservoirs, which are mostly used as water reserves for the relatively dry landscapes of Franconia. These includes the waters of the Franconian Lake District, which was established in the 1970s and is also a tourist attraction. The heart of these lakes is the Großer Brombachsee, which has an area of 8.7 km² and is thus the largest waterbody in Franconia by surface area.

Hills, mountains and plains

Several Central Upland ranges dominate the Franconian countryside. In the southeast, Franconia is shielded from the rest of Bavaria by the Franconian Jura. In the east, the Fichtel Mountains form the border; in the north are Franconian Forest, the Thuringian Forest, the Rhön Mountains and the Spessart form a kind of natural barrier. To the west are the Franconian Heights and the Swabian-Franconian Forest. In the Franconian part of South Hesse is the Odenwald. Parts of the southern Thuringian Forest border on Franconia. The most important hill ranges in the interior of the region are the Steigerwald and the Franconian Jura with their sub-ranges of Hahnenkamm and Franconian Switzerland. The highest mountain in Franconia is the Schneeberg in the Fichtel Mountains which is 1,051 m above sea level (NHN).[14] Other well-known mountains include the Ochsenkopf (1,024m[14]), the Kreuzberg (927.8m[14]) and the Hesselberg (689.4m[14]). The outliers of the region include the Hesselberg and the Gleichberge. The lowest point in Franconia is the water level of the River Main in Kahl which lies at a height of 100 metres above sea level.

In addition to the hill and mountain ranges, there are also several very level areas, including the Middle Franconian Basin and the Hohenlohe Plain. In the south of Franconia are smaller parts of the flat Nördlinger Ries, one of the best preserved impact craters on earth.

Forests, reserves, flora and fauna

Franconia's flora is dominated by deciduous and coniferous forests. Natural forests in Franconia occur mainly in the ranges of the Spessart, Franconian Forest, Odenwald and Steigerwald. The Nuremberg Reichswald is another great forest, located within the metropolitan region of Nuremberg. Other large areas of forest in the region are the Mönchswald, the Reichsforst in the Fichtel Mountains and the Selb Forest. In the river valleys along the Main and Tauber, the countryside was developed for viticulture. In Spessart there are great oak forests. Also widespread are calcareous grasslands, extensively used pastures on very oligotrophic, poor sites. In particular, the southern Franconian Jura, with the Altmühl Valley, is characterized by poor grassland of this type. Many of these places have been designated as a protected areas.

Franconia has several regions with sandy habitats that are unique for south Germany and are protected as the so-called Sand Belt of Franconia or Sandachse Franken.[15] When the Altmühlsee reservoir was built, a bird island was created and designated as a nature reserve where a variety of birds nest. Another important reserve is the Black Moor in the Rhön, which is one of the most important bog areas in Central Europe.[16] A well known reserve is the Luisenburg Rock Labyrinth at Wunsiedel, a felsenmeer of granite blocks up to several metres across. The establishment of the first Franconian national park in the Steigerwald caused controversy and its designation was rejected in July 2011 by the Bavarian government.[17] The reason was the negative attitude of local population. Conservationists are now demanding protection for parts of the Steigerwald by nominating it for a World Heritage Site.[17] There are several nature parks in Franconia, including the Altmühl Valley Nature Park, which, since 1969, has been one of the largest in Germany.[18]

Other nature parks are the Swabian-Franconian Forest Nature Park in Baden-Württemberg, and the nature parks of Bavarian Rhön, Fichtel Mountains, Franconian Heights, Franconian Forest, Franconian Switzerland-Veldenstein Forest, Haßberge, Spessart and Steigerwald in Bavaria, as well as the Bergstraße-Odenwald Nature Park which straddles Bavaria, Baden-Württemberg and Hesse. Nature parks cover almost half the area of Franconia.[19]

In 1991 UNESCO recognised the Rhön as a biosphere reserve.[20] Among the most picturesque geotopes in Bavaria, are the Franconian sites of Fossa Carolina, the Twelve Apostle Rocks (Zwölf-Apostel-Felsen), the Ehrenbürg, the cave ruins of Riesenburg and the lake of Frickenhäuser See.[21] The European Bird Reserves in Franconia are found mainly in uplands like the Steigerwald, in large forests like Nuremberg's Imperial Forest or along rivers like the Altmühl.[22] There are also numerous Special Areas of Conservation and protected landscapes. In Franconia there are very many tufas, raised stream beds near river sources within the karst landscape that are known as 'stone runnels' (Steinerne Rinnen). There are protected examples at Heidenheim and Wolfsbronn.

Like large parts of Germany, Franconia only has a few large species of wild animal. Forest dwellers include various species of marten, fallow deer, red deer, roe deer, wild boar and fox. In natural areas such as the Fichtel mountains there are populations of lynx and capercaillie,[23] and beaver and otter have grown in numbers. There are occasional sightings of animals that had long been extinct in Central Europe, for example, the wolf.[24]

Geology

General

Only in the extreme northeast of Franconia and in the Spessart are there Variscan outcrops of the crystalline basement, which were uplifted from below the surface when the Alps exerted a northwards-oriented pressure. These are rocks of pre-Permian vintage, which were folded during various stages of Variscan orogeny in the Late Palaeozoic - before about 380 to 300 million years ago - and, in places, were metamorphosed under high pressure and temperature or were crystallized by ascending magma in the Earth's crust.[25] Rocks which were unchanged or only lightly metamorphosed, because they had been deformed at shallow crustal depths, include the Lower Carboniferous shale and greywacke of Franconian Forest. The Fichtel mountains, the Münchberg Plateau and the Spessart, by contrast, have more metamorphic rocks (phyllite, schist, amphibolite, gneiss). The Fichtel mountains are also characterized by large granite bodies, called post-kinematic plutons which, in the late phase of Variscan orogeny, intruded into the metamorphic rocks. In most cases these are S-type granites whose melting was caused by heated-up sedimentary rocks sunk deep into the Earth's crust.[26] While the Fichtel and Franconian Forest can be assigned to the Saxo-Thuringian Zone of Central European Variscan orogeny, the Spessart belongs to the Central German Crystalline Zone.[25] The Münchberg mass is variously attributed to the Saxo-Thuringian or Moldanubian Zones.[27]

A substantially larger part of the shallow subsurface in Franconia comprises Mesozoic, unmetamorphosed, unfolded rocks of the South German Scarplands.[28] The regional geological element of the South German Scarplands is the Franconian Platform (Süddeutsche Großscholle).[29] At the so-called Franconian Line, a significant fault line, the Saxo-Thuringian-Moldanubian basement was uplifted in places up to 2000 m above the Franconian Platform.[30] The western two-thirds of Franconia is dominated by the Triassic with its sandstones, siltstones and claystones (so-called siliciclastics) of the bunter sandstone; the limestones and marls of the Muschelkalk and the mixed, but predominantly siliciclastic, sedimentary rocks of the Keuper. In the Rhön, the Triassic rocks are overlain and intruded by volcanic rock (basalts, basanites, phonolites and trachytes) of the Tertiary. The eastern third of Franconia is dominated by the Jurassic rocks of the Franconian Jura, with the dark shales of the Black Jura, the shales and ferruginous sandstones of the Brown Jura and, the weathering-resistant limestones and dolomitic rocks of the White Jura, which stand out from the landscape and form the actual ridge of the Franconian Jura itself.[28] In the Jura, mostly siliciclastic sedimentary rocks formed in the Cretaceous have survived.

The Mesozoic sediments have been deposited in largescale basin areas. During the Triassic, the Franconian part of these depressions was often part of the mainland, in the Jurassic it was covered for most of the time by a marginal sea of the western Tethys Ocean. At the time when the limestones and dolomites of the White Jura were being deposited, this sea was divided into sponge reefs and intervening lagoons. The reef bodies and the fine-grained lagoon limestones and marls are the material from which the majority of the Franconian Jura is composed today.[31] Following a drop in the sea level towards the end of the Upper Jurassic, larger areas also became part of the mainland at the beginning of the subsequent Cretaceous period. During the Upper Cretaceous, the sea advanced again up to the area of the Franconian Jura. At the end of the Cretaceous, the sea then retreated again from the region.[31] In addition, large parts of South and Central Germany experienced a general uplift -or in areas where the basement had broken through a substantial uplift - the course of formation of the Alps during the Tertiary. Since then, Franconia has been mainly influenced by erosion and weathering (especially in the Jura in the form of karst), which has ultimately led to formation of today's landscapes.

Fossils

The oldest macrofossils in Franconia, which are also the oldest in Bavaria, are archaeocyatha, sponge-like, goblet-shaped marine organisms, which were discovered in 2013 in a limestone block of Late Lower Cambrian age, about 520 million years old. The block comes from the vicinity Schwarzenbach am Wald from the so-called Heinersreuth Block Conglomerate (Heinersreuther Blockkonglomerat), a Lower Carboniferous wildflysch. However, the aforementioned archaeocyathids are not three-dimensional fossils, but two-dimensional thin sections. These thin sections had already been prepared and investigated in the 1970s but the archaeocyathids among them were apparently overlooked at that time.[32]

Better known and more highly respected fossil finds in Franconia come from the unfolded sedimentary rocks of the Triassic and Jurassic. The bunter sandstone, however, only has a relatively small number of preserved whole fossils. Much more commonly, it contains trace fossils, especially the tetrapod footprints of Chirotherium. The type locality for these animal tracks is Hildburghausen in the Thuringian part of Franconia, where it occurs in the so-called Thuringian Chirotherium Sandstone (Thüringer Chirotheriensandstein, main Middle Bunter Sandstone).[33] Chirotherium is also found in the Bavarian and Württemberg parts of Franconia. Sites include Aura near Bad Kissingen, Karbach, Gambach and Külsheim.[34] There the deposits are somewhat younger (Upper Bunter Sandstone), and the corresponding stratigraphic interval is called the Franconian Chirotherium Beds (Fränkische Chirotherienschichten).[34] Among the less significant body fossil records of vertebrates are the procolophonid Anomoiodon liliensterni from Reurieth in the Thuringian part of Franconia[35] and Koiloskiosaurus coburgiensis from Mittelberg near Coburg,[36] both from the Thuringian Chirotherium Sandstone, and the Temnospondyle Mastodonsaurus ingens (possibly identical with the mastodonsaurus, Heptasaurus cappelensis) from the Upper Bunter at Gambach.[37][38]

As early as the first decade of the 19th century George, Count of Münster began systematic fossil gathering and digs and in the Upper Muschelkalk at Bayreuth. For example, the Oschenberg hill near Laineck became the type locality of two relatively well-known marine reptiles of the Triassic period, later found in other parts of Central Europe: the "flat tooth lizard", Placodus[39] and the "false lizard", Nothosaurus.[40]

In Franconia's middle Keuper (the Feuerletten) is one of the best known and most common species of dinosaurs of Central Europe: Plateosaurus engelhardti, an early representative of the sauropodomorpha. Its type locality is located at Heroldsberg south of Nuremberg. When the remains of Plateosaurus were first discovered there in 1834, it was the first discovery of a dinosaur on German soil, and this occurred even before the name "dinosauria" was coined. Another important Plateosaurus find in Franconia was made at Ellingen.[41]

Far more famous than Plateosaurus, Placodus and Nothosaurus is the Archaeopteryx, probably the first bird geologically. It was discovered in the southern Franconian Jura, inter alia at the famous fossil site of Solnhofen in the Solnhofen Platform Limestone (Solnhofener Plattenkalk, (Solnhofen-Formation, early Tithonian, Upper Jurassic). In addition to Archaeopteryx, in the very fine-grained, laminated lagoon limestones are the pterosaur Pterodactylus and various bony fishes as well as numerous extremely detailed examples of invertebrates e.g. feather stars and dragonflies. Eichstätt is the other "big" and similarly famous fossil locality in the Solnhofen Formation, situated on the southern edge of the Jura in Upper Bavaria. Here, as well as Archaeopteryx, the theropod dinosaurs, Compsognathus and Juravenator, were found.

An inglorious episode in the history of paleontology took place in Franconia: fake fossils, known as Beringer's Lying Stones, were acquired in the 1720s by Würzburg doctor and naturalist, Johann Beringer, for a lot of money and then described in a monograph, along with genuine fossils from the Würzburg area. However, it is not entirely clear whether the Beringer forgeries were actually planted or whether he himself was responsible for the fraud.[42]

Climate

Franconia has a humid cool temperate transitional climate, which is neither very continental nor very maritime. The average monthly temperatures vary depending on the area between about -1 to -2 °C in January and 17 to 19 °C in August, but may reach a peak of about 35 °C for a few days in the summer, especially in the large cities. The climate of Franconia is sunny and relatively warm. For part of the summer, for example, Lower Franconia is one the sunniest areas in Germany. Daily temperatures in the Bavarian part of Franconia are an average of 0.1 °C higher than the average for Bavaria as a whole.[43] Relatively less rain falls in Franconia, and likewise in the rest of North Bavaria rain than is usual for its geographic location; even summer storms are often less powerful than in other areas of South Germany.[44] In southern Bavaria about 2,000 mm of precipitation falls annually and almost three times as much as in parts of Franconia (about 500–900 mm) in the rain shadow of the Spessart, Rhön and Odenwald.[45]

Quality of life

Franconia, as part of Germany, has a high quality of life. In the Worldwide Quality of Living Survey by Mercer in 2010, the city of Nuremberg was one of the top 25 cities in the world in terms of quality of life and came sixth in Germany.[46] In environmental ranking Nuremberg came thirteenth in the world and was the best German city[46] In a survey by the German magazine, Focus, on quality of life in 2014, the districts of Eichstätt and Fürth were among the top positions in the table.[47] In the Glücksatlas by Deutsche Post Franconia achieved some of the highest scores,[48] but the region slipped in 2013 to 13th place out of 19.[49]

History

Name

Franconia is named after the Franks, a Germanic tribe who conquered most of Western Europe by the middle of the 8th century. Despite its name, Franconia is not the homeland of the Franks, but rather owes its name to being partially settled by Franks from the Rhineland during the 7th century following the defeat of the Alamanni and Thuringians who had dominated the region earlier.[50]

At the beginning of the 10th century a Duchy of Franconia (German: Herzogtum Franken) was established within East Francia, which comprised modern Hesse, Palatinate, parts of Baden-Württemberg and most of today's Franconia. After the dissolution of the so-called Stem duchy of Franconia, the Holy Roman Emperors created the Franconian Circle (German Fränkischer Reichskreis) in 1500 to embrace the principalities that grew out of the eastern half of the former duchy. The territory of the Franconian Circle roughly corresponds with modern Franconia. The title of a Duke of Franconia was claimed by the Würzburg bishops until 1803 and by the kings of Bavaria until 1918.[51] Examples of Franconian cities founded by Frankish noblemen are Würzburg, first mentioned in the 7th century, Ansbach, first mentioned in 748, and Weissenburg, founded in the 7th century.[52]

Early history and Antiquity

Fossil finds show that the region was already settled by primitive man, Homo erectus, in the middle Ice Age about 600,000 years ago. Probably the oldest human remains in the Bavarian part of Franconia were found in the cave ruins of Hunas at Pommelsbrunn in the county of Nuremberg Land.[53] In the late Bronze Age, the region was probably only sparsely inhabited, as few noble metals occur here and the soils are only moderately fertile.[54] In the subsequent Iron Age (from about 800 B.C.) the Celts become the first nation to be discernible in the region. In northern Franconia they built a chain of hill forts as a line of defence against the Germanii advancing from the north. On the Staffelberg they built a powerful settlement, to which Ptolemy the name oppidum Menosgada,[55] and on the Gleichberge is the largest surviving oppidum in Central Germany, the Steinsburg. With the increased expansion of Rome in the first century B.C. and the simultaneous advance of the Elbe Germanic tribes from the north, the Celtic culture began to fall into decline. The southern parts of present-day Franconia soon fell under Roman control; however, most of the region remained in Free Germania. Initially Rome tried extend its direct influence far to the northeast; in the longer term, however, the Germanic-Roman frontier formed further southwest.[56]

Under the emperors, Domitian (81-96), Trajan (98-117) and Hadrian (117-138), the Rhaetian Limes was built as a border facing the Germanic tribes to the north. This defensive line ran through the south of Franconia and described an arc across the region whose northernmost point lay at present-day Gunzenhausen. To protect it, the Romans built several forts like Biriciana at Weißenburg, but by the mid-third century, the border could no longer be maintained and by 250 A.D. the Alemanni occupied the areas up to the Danube. Fortified settlements such as the Gelbe Bürg at Dittenheim controlled the new areas.[57] More such Gau forts have been detected north of the former Limes as well. To which tribe their occupants belonged is unknown in most cases. However, it is likely that it was mainly Alemanni and Juthungi in especially in the south.[58] By contrast, it was the Burgundians who settled on the Lower and Middle Main.[58] Many of these hill forts appear to have been destroyed, however, no later than 500 A.D. The reasons are not entirely clear, but it could have been as a result of invasions by the Huns which thus triggered the Great Migration. In many cases, however, it was probably conquest by the Franks that spelt the end of these hilltop settlements.[57]

Middle Ages

With their victories over the heartlands of the Alamanni and Thuringians in the 6th century, the present region of Franconia also fell to the Franks.[2] After the division of the Frankish Empire, East Francia (Francia orientialis) was formed from the territories of the dioceses of Mainz, Worms, Würzburg and Speyer. Later, the diocese of Bamberg was added.[2] In the 7th century, the Slavs started to populate the northeastern parts of the region from the east, because the area of today's Upper Franconia was very sparsely populated (Bavaria Slavica).[59] However, in the 10th and 11th centuries, they largely gave up their own language and cultural tradition. The majority of the population of Franconia was pagan well into the Early Middle Ages, The first people to spread the Christian faith strongly were wandering Irish Anglo-Saxon monks in the early 7th century. Saint Kilian, who together with his companions, Saint Colman and Saint Totnan are considered to be the apostles to the Franks, suffering martyrdom in Würzburg in the late 7th century, probably did not encounter any pagans in the ducal court. It was probably Saint Boniface who carried the Christian mission deep into the heart of the ordinary population of Franconia.[60]

In the mid-9th century the tribal Duchy of Franconia emerged, one of the five tribal or stem duchies of East Francia.[61] The territory of the stem duchy was far bigger than modern Franconia and covered the whole of present-day Hesse, northern Baden-Württemberg, southern Thuringia, large parts of Rhineland-Palatinate and parts of the Franconian provinces in Bavaria. It extended as far west as Speyer, Mainz, and Worms (west of the Rhine) and even included Frankfurt ("ford of the Franks"). In the early 10th century, the Babenbergs and Conradines fought for power in Franconia. Ultimately this discord led to the Babenberg Feud which was fuelled and controlled by the crown. The outcome of this feud meant the loss of power for the Babenbergs, but indirectly resulted in the Conradines winning the crown of East Francia. Sometime around 906, Conrad succeeded in establishing his ducal hegemony over Franconia, but when the direct Carolingian male line failed in 911, Conrad was acclaimed King of the Germans, largely because of his weak position in his own duchy. Franconia, like Alamannia was fairly fragmented and the duke's position was often disputed between the chief families. Conrad had granted Franconia to his brother Eberhard on his succession, but when Eberhard rebelled against Otto I in 938, he was deposed from his duchy, which disintegrated in 939 on Eberhard's death into West or Rhenish Franconia (Francia Rhenensis), and East Franconia (Francia Orientalis)[note 1] and was directly subordinated to the Reich. Only after that was the former Francia Orientalis considered to be under the sphere of the bishops of Würzburg as the true Franconia, its territory gradually shrinking to its present area.[2]

Meanwhile, the inhabitants of parts of present-day Upper and Middle Franconia, who were not under the control of Würzburg, probably also considered themselves to be Franks at that time, and certainly their dialect distinguished them from the inhabitants of Bavaria and Swabia.[62]

Unlike the other stem duchies, Franconia became the homeland and power base of East Frankish and German kings after the Ottonians died out in 1024.[61] As a result, in the High Middle Ages, the region did not become a strong regional force such as those which formed in Saxony, Bavaria and Swabia. In 1007, the later canonized Henry II founded the Bishopric of Bamberg and endowed it with rich estates.[63] Bamberg became a favoured Pfalz and an important centre of the Empire.[63] Because parts of the Bishopric of Würzburg also fell to Bamberg, Würzburg was enfeoffed several royal estates by King Henry II by way of compensation.[64]

From the 12th century Nuremberg Castle was the seat of the Burgraviate of Nuremberg. The burgraviate was ruled from about 1190 by the Zollerns, the Franconian line of the later House of Hohenzollern, which provided the German emperors of the 19th and 20th century.[65] Under the Hohenstaufen kings, Conrad III and Frederick Barbarossa, Franconia became the centre of power in the Empire. During the time when there was no emperor, the Interregnum (1254–1273), some territorial princes became ever more powerful. After the Interregnum, however, the rulers succeeded in re-establishing a stronger royal lordship in Franconia.[66] Franconia soon played an important role again for the monarchy at the time of Rudolf of Habsburg; the itineraries of his successors showing their preference for the Rhine-Main region. In 1376 the Swabian League of Cities was founded and was joined later by several Franconian imperial cities.[67] During the 13th century the Teutonic Order was formed, taking over its first possession in Franconia in 1209, the Bailiwick of Franconia. The foundation of many schools and hospitals and the construction of numerous churches and castles in this area goes back to the work of this Roman Catholic military order. The residence place of the bailiwick was at Ellingen until 1789 when it was transferred to today's Bad Mergentheim.[68] Other orders such as the Knights Templar could not gain a foothold in Franconia; the Order of St. John worked in the Bishopric of Würzburg and had short term commands.[69]

Successor states of East Francia

As of the 13th century, the following states, among others, had formed in the territory of the former Duchy:

|

|

Early Modern Period

On 2 July 1500 during the reign of Emperor Maximilian I, as part of the Imperial Reform Movement, the Empire was divided into Imperial Circles. This led in 1512 to the formation of the Franconian Circle.[3] Seen from a modern perspective, the Franconian Circle may be viewed as an important basis for the sense of a common Franconian identity that exists today.[8] The Franconian Circle also shaped the geographical limits of the present-day Franconia.[62] In the late Middle Ages and Early Modern Period, the Imperial Circle was severely affected by Kleinstaaterei, the patchwork of tiny states in this region of Germany. As during the late Middle Ages, the bishops of Würzburg used the nominal title of Duke of Franconia during the time of the Imperial Circle.[70] In 1559, the Franconian Circle was given jurisdiction over coinage (Münzaufsicht) and, in 1572, was the only Circle to issue its own police ordinance.[71][72]

Members of the Franconian Circle included the imperial cities, the prince-bishoprics, the Bailiwick of Franconia of the Teutonic Order and several counties. The Imperial Knights with their tiny territories, of which there was a particularly large number in Franconia, were outside the Circle assembly and, until 1806, formed the Franconian Knights Circle (Fränkischer Ritterkreis) consisting of six Knights' Cantons. Because the extent of Franconia, already referred to above, is disputed, there were many areas that might be counted as part of Franconia today, that lay outside the Franconian Circle. For example, the area of Aschaffenburg belonged to Electoral Mainz and was a part of the Electoral Rhenish Circle, the area of Coburg belonged to the Upper Saxon Circle and the Heilbronn area to the Swabian Circle. In the 16th century, the College of Franconian Counts was founded to represent the interests of the counts in Franconia.[73]

Franconia played an important role in the spread of the Reformation initiated by Martin Luther,[74] Nuremberg being one of the places where the Luther Bible was printed.[75] The majority of other Franconian imperial cities and imperial knights embraced the new confession.[76] In the course of the counter-reformation several regions of Franconia returned to Catholicism, however, and there was also an increase in witch trials.[77] In addition to Lutheranism, the radical reformatory baptist movement spread early on across the Franconian area. Important Baptist centres were Königsberg and Nuremberg.[78][79]

In 1525, the burden of heavy taxation and socage combined with new, liberal ideas that chimed with the Reformation movement, unleashed the German Peasants' War. The Würzburg area was particularly hard hit with numerous castles and monasteries being burned down.[80] In the end, however, the uprisings were suppressed and for centuries the lowest strata of society were excluded from all political activity.

From 1552, Margrave Albert Alcibiades attempted to break the supremacy of the mighty imperial city of Nuremberg and to secularise the ecclesial estates in the Second Margrave War,[81] to create a duchy over which he would rule.[82] Large areas of Franconia were eventually devastated in the fighting until King Ferdinand I together with several dukes and princes decided to overthrow Albert.

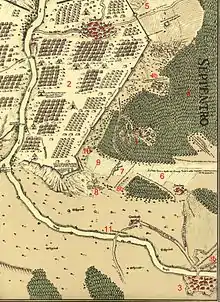

In 1608, the reformed princes merged into a so-called Union within the Empire. In Franconia, the margraves of Ansbach and Bayreuth as well as the imperial cities were part of this alliance. The Catholic side responded in 1609 with a counter-alliance, the League. The conflicts between the two camps ultimately resulted in the Thirty Years' War, which was the greatest strain on the cohesion of the Franconian Circle[83] Initially, Franconia was not a theatre of war, although marauding armies repeatedly crossed its territory. However, in 1631, Swedish troops under Gustavus Adolphus advanced into Franconia and established a large encampment in summer 1632 around Nuremberg.[84] However, the Swedes lost the Battle of the Alte Veste against Wallenstein's troops and eventually withdrew. Franconia was one of the poorest regions in the Empire and lost its imperial political significance.[85] During the course of the war, about half the local population lost their lives. To compensate for these losses about 150,000 displaced Protestants settled in Protestant areas, including Austrian exiles.[86]

Franconia never developed into a unified territorial state, because the patchwork quilt of small states (Kleinstaaterei) survived the Middle Ages and lasted until the 18th century.[87] As a result, the Franconian Circle had the important task of preserving peace, preventing abuses and to repairing war damage and had a regulatory role in the region until the end of the Holy Roman Empire. Until the War of the Spanish Succession, the Circle had become an almost independent organization and joined the Grand Alliance against Louis XIV as an almost sovereign state. The Circle also developed early forms of a welfare state.[87] It also played a major role in the control of disease during the 16th and 17th centuries.[88] After Charles Alexander abdicated in 1792, the former margraviates of Ansbach and Bayreuth were annexed by Prussia.[89][90] Karl August Freiherr von Hardenberg was appointed as governor of these areas by Prussia.[90]

Later Modern Period

Most of modern-day Franconia became part of Bavaria in 1803 thanks to Bavaria's alliance with Napoleon. Culturally it is in many ways different from Bavaria proper ("Altbayern", Old Bavaria), however. The ancient name was resurrected in 1837 by Ludwig I of Bavaria. During the Nazi period, Bavaria was broken up into several different Gaue, including Franconia and Main-Franconia.

19th century

In 1803, what was to become the Kingdom of Bavaria was given large parts of Franconia through the enactment of the Reichsdeputationshauptschluss under pressure from Napoleon for secularization and mediatisation.[91] In 1806, the Act of Confederation led to stronger ties between Bavaria, Württemberg, Baden and other areas with France, whereupon the Holy Roman Empire including the Franconian Circle fell apart.[92][93] As a reward Bavaria was promised other estates, including the city of Nuremberg.[92] In the so-called Rittersturm of 1803, Bavaria, Württemberg and Baden seized the territories of the Imperial Knights and Franconian nobility, whose estates were often no bigger than a few parishes, even though the Reichsdeputationshauptschluss had not authorised this.[70] In 1806 and 1810, Prussia had to release the territories of Ansbach and Bayreuth, which it had annexed in 1792, to Bavaria, whereby Prussia lost its supremacy in the region.[90]

In 1814, as a result of the Congress of Vienna, the territories of the Principality of Aschaffenburg and Grand Duchy of Würzburg went to the Kingdom of Bavaria. In order to merge the patchwork quilt of small states in Franconia and Swabia into a greater Bavaria, Maximilian Joseph Montgelas reformed the political structure.[94][95]I Out of this in January 1838 emerged the Franconian provinces with their present names of Middle, Upper and Lower Franconia.[96] Considerable resentment arose in parts of the Franconian territories over their new membership of Bavaria.[97] There were liberal demands for republican structures which erupted in the revolts of 1848 and 1849 and the Gaibach Festival in 1832.[98][99] On the one hand the reconciliation policy of the Wittelsbachs[97] and Montgelas' aforementioned policy of unification, and, on the other hand, the inclusion of Bavaria in the German Empire in 1871, which weakened her power Bavaria slightly, the conflict between Franconia and Bavaria eased considerably.

From 1836 to 1846, the Kingdom of Bavaria built the Ludwig Canal from Bamberg to Kelheim, which was only abandoned in 1950.[100] However, the canal lost much of its importance shortly after the arrival of the railways. Between 1843 and 1854, the Ludwig South-North Railway was established within Franconia, which ran from Lindau on Lake Constance via Nuremberg, Bamberg and Kulmbach to Hof. The first locomotive to run on German soil steamed 1835 from Nuremberg to Fürth on 7 December 1835.

20th century

After the First World War the monarchy in Bavaria was abolished, but the state could not agree on a compromise between a Soviet system and parliamentarianism. This caused fighting between the opposing camps and the then prime minister was shot. As a result, the government fled to Bamberg in 1919, where the Bamberg Constitution was adopted while, in Munich, the Bavarian Soviet Republic reigned briefly.[101] In 1919 the Free State of Coburg voted in a referendum against joining Thuringia and was instead united with Bavaria on 1 July 1920.[101]

During the Nazi era Nuremberg played a prominent role in the self-expression of the National Socialists as the permanent seat of the Nazi Party.[102] Gunzenhausen made its mark as one of the first towns in the Reich itself to exercise discrimination against the Jewish population. The first Hitler Monument in Germany was established there in April 1933. On 25 March 1934 the first anti-Jewish pogrom in Bavaria took place in Gunzenhausen. The attack brought the town negative press coverage worldwide.[103] On 15 September, a Reichstag was specially convened in Nuremberg for the purpose of passing the Nuremberg Laws, under which the antisemitic ideology of the Nazis became a legal basis for such actions.[104]

Like all parts of the German Reich, Franconia was badly affected by Allied air raids. Nuremberg, as a major industrial centre and transportation hub, was hit particularly hard. Between 1940 and 1945 the city was the target of dozens of air raids. Many other places were also affected by air raids. For example, the air raid on 4 December 1944 on Heilbronn[105] and the bombing of Würzburg on 16 March 1945, in which both old towns were almost completely destroyed, was a disaster for both cities. By contrast, the old town of Bamberg was almost completely spared.[106] In order to protect cultural artefacts, the historic art bunker was built below Nuremberg Castle.[107] In the closing stages of the Second World War, at the end of March and April 1945, Franconian towns and cities were captured by formations of the US Army who advanced from the west after the failure of the Battle of the Bulge and Operation Nordwind. The Battle of Nuremberg lasted five days and resulted in at least 901 deaths. The Battle of Crailsheim lasted 16 days, the Battle of Würzburg seven and the Battle of Merkendorf three days.

Following the unconditional surrender on 8 May 1945, Bavarian Franconia became part of the American zone of occupation; whilst South Thuringia, with the exception of smaller enclaves like Ostheim, became part of the Soviet zone and the Franconian parts of today's Baden-Württemberg also went to the American zone[108] The most important part of the Allied prosecution programme against leaders of the Nazi regime were the Nuremberg Trials against leaders of the German Empire during the Nazi era, held from 20 November 1945 to 14 April 1949.[109] The Nuremberg Trials are considered a breakthrough for the principle that, for a core set of crimes, there is no immunity from prosecution. For the first time, the representatives of a sovereign state were held accountable for their actions. In autumn 1946, the Free State of Bavaria was reconstituted with the enactment of the Bavarian Constitution.[110]

The state of Württemberg-Baden was founded on 19 September 1945.[111] On 25 April 1952 this state merged with Baden and Württemberg-Hohenzollern (both from the former French occupation zone) to create the present state of Baden-Württemberg.[112] On 1 December 1945 the state of Hesse was founded. Beginning in 1945, refugees and displaced persons from Eastern Europe were settled particularly in rural areas.[113] After 1945, Bavaria and Baden-Württemberg managed the transition from economies that were predominantly agriculture to become leading industrial states in the so-called Wirtschaftswunder. In Lower and Upper Franconia, there was still the problem, however, of the zone along the Inner German Border which was a long way from the markets for its agricultural produce, and was affected by migration and relatively high unemployment,[114] which is why these areas received special support from federal and state governments.

By contrast, the state of Thuringia was restored by the Soviets in 1945. On 7 October 1949 the German Democratic Republic, commonly known as East Germany, was founded. In 1952 in the course of the 1952 administrative reform in East Germany, the state of Thuringia was relieved of its function.[115] The Soviet occupying forces exacted a high level of reparations (especially the dismantling of industrial facilities) which made the initial economic conditions in East Germany very difficult.[116] Along with the failed economic policies of the GDR, this led to a general frustration that fuelled the uprising of 17 June. There were protests in the Franconian territories too, for example in Schmalkalden.[117] The village of Mödlareuth became famous because, for 41 years, it was divided by the Inner German Border and was nicknamed 'Little Berlin. After Die Wende, the fall of the Berlin Wall on 9 November 1989 and reunification on 3 October 1990, made possible mainly by mass demonstrations in East Germany and local exodus of East Germans, the state of Thuringia was reformed with effect from 14 October 1990.[115]

In the years from 1971 to 1980 an administrative reform was carried out in Bavaria with the aim of creating more efficient municipalities (Gemeinden) and counties (Landkreise). Against sometimes great protests by the population, the number of municipalities was reduced by a third and the number of counties by about a half. Among the changes was the transfer of the Middle Franconian county of Eichstätt to Upper Bavaria. On 18 May 2006, the Bavarian Landtag approved the introduction of Franconia Day (Tag der Franken) in the Franconian territories of the free state.[118]

Since Die Wende, new markets have opened up for the Franconian region of Bavaria in the new (formerly East German) federal states and the Czech Republic, enabling the economy to recover.[119] Today, Franconia is in the centre of the EU (at Oberwestern near Westerngrund; geographical centre of the EU 50.117286°N 9.247768°E)[120]

Contemporary Franconia

While Old Bavaria is overwhelmingly Roman Catholic, Franconia is a mixed area. Lower Franconia and the western half of Upper Franconia (Bamberg, Lichtenfels, Kronach) is predominantly Catholic, while most of Middle and the eastern half of Upper Franconia (Bayreuth, Hof, Kulmbach) are predominantly Protestant (Evangelical Church in Germany). The city of Fürth in Middle Franconia historically (before the Nazi era) had a large Jewish population; Henry Kissinger was born there.

Population

A large part of the population of Franconia, which has a population of five million,[121] consider themselves Franconians (Franken, in German homonymous with the name of the historical Franks), a sub-ethnic group of the German people alongside Alemanni, Swabians, Bavarians, Thuringians and Saxons. Such an ethnic identity is generally not shared by other parts of the Franconian-speaking area (members of which may identify as Rhine Franconians (Rheinfranken) or Moselle Franconians (Moselfranken).

The Free State of Bavaria counts Franconians as one of the "four tribes of Bavaria" (vier Stämme Bayerns), alongside Bavarians, Swabians and Sudeten Germans.[122]

Towns and cities

With the exception of Heilbronn, all cities in Franconia and all towns with a population of over 50,000 are within the Free State of Bavaria. The five cities of Franconia are Nuremberg, Würzburg, Fürth, Heilbronn and Erlangen. In Middle Franconia, in the metropolitan region of Nuremberg there is a densely populated urban area consisting of Nuremberg, Fürth, Erlangen and Schwabach. Nuremberg is the fourteenth largest city in Germany and the second largest in Bavaria.

The largest settlements in Baden-Württemberg's Franconian region are Heilbronn (pop: 117,531), Schwäbisch Hall (37,096) and Crailsheim (32,417).[123] The largest places in the Thuringian part are Suhl (35,665), Sonneberg (23,796) and Meiningen (20,966).[124] The largest place in the Hessian part of Franconia is Gersfeld with just 5,512 inhabitants.[125] The largest cities within Bavaria are Nuremberg (495,121), Würzburg (124,577), Fürth (118,358) and Erlangen (105,412).[126]

In the Middle Ages Franconia, with its numerous towns, was separate and not part of other territories such as the Duchy of Bavaria.[127] In the late medieval period it was dominated by mainly smaller towns with a few hundred to a thousand inhabitants, whose size barely distinguished them from the villages. Many towns grew up along large rivers or were founded by the prince-bishops and nobility. Even the Hohenstaufens operated in many towns, most of which later became Imperial Cities with a strong orientation towards Nuremberg.[127] The smallest town in Franconia is Thuringia's Ummerstadt with 487 inhabitants.[124]

Language

German is the official language and also the lingua franca. Numerous other languages are spoken that come from other language regions or the native countries of immigrants.

East Franconian German, the dialect spoken in Franconia, is very different from the Austro-Bavarian dialect. Most Franconians do not call themselves Bavarians. Even though there is no Franconian state, red and white are regarded as the state colours (Landesfarben) of Franconia.

Christianity

The proportion of Roman Catholics and Protestants among the population of Franconia is roughly the same, but varies from region to region.[128] Large areas of Middle and Upper Franconia are mainly Protestant.[128] The denominational orientation today still reflects the territorial structure of Franconia at the time of the Franconian Circle. For example, regions, that used to be under the care of the bishoprics of Bamberg, Würzburg and Eichstätt, are mainly Catholic today. On the other hand, all former territories of the imperial cities and the margraviates of Ansbach and Bayreuth have remained mainly Lutheran. The region around the city of Erlangen, which belonged to the Margraviate of Bayreuth, was a refuge for the Huguenots who fled there after the St. Bartholomew's Day massacre in France.[129] Following the success of the Reformation in Nuremberg under Andreas Osiander, it had been an exclusively Protestant imperial city and belonged to the Protestant league of imperial states, the Corpus Evangelicorum, within the Reichstag.[130] Subsequent historical events such as the stream of refugees after the Second World War and the increasing mobility of the population has since blurred denominational geographical boundaries, however.

The influx of immigrants from Eastern Europe has also seen the establishment of an Orthodox community in Franconia. The Romanian Orthodox Metropolis of Germany, Central and Northern Europe has its headquarters in Nuremberg.

Judaism

Before the Nazi era Franconia was as a region with significant Jewish communities, most of whom were Ashkenazi Jews.[131] The first Jewish communities appeared in Franconia in the 12th and 13th centuries and thus later than, for example, in Regensburg. In the Middle Ages, Franconia was a stronghold of Torah studies. But Franconia also began to exclude the Jewish populations particularly early on. For example, there were two Jewish massacres - the Rintfleisch massacres of 1298 and the Armleder Uprising of 1336-1338 - and in the 15th and 16th centuries many cities exiled their Jewish populations, which is why many Jews settled in rural communities. Franconia also rose to early prominence in the discrimination of Jews during the Nazi era.[132] One of the first casualties of the organized Nazi persecution of Jews took place on 21 March in Künzelsau and on 25/26 March 1933 in Creglingen, where police and SA troops under the leadership of Standartenführer Fritz Klein led a so-called "weapons search operations".[133][134] Whilst, in 1818, about 65 per cent of Bavarian Jews lived in the Bavarian part of Franconia,[135] today there are only Jewish communities in Bamberg, Bayreuth, Erlangen, Fürth, Hof, Nuremberg and Würzburg[136] and in Heilbronn in Baden-Württemberg.

Islam

Adherents of Islam continue to grow, especially in the larger cities, due to the influx of gastarbeiters and other immigrants from Muslim countries. As a result, many 'backyard mosques' (Hinterhofmoscheen) have sprung up, which are gradually being replaced by purpose-built mosques.

Culture

Franconia has almost 300 small breweries.[137] The northwestern parts, the areas around river Main called Franconian wine region also produce a lot of wine. Food typical for the region includes Bratwurst (especially the famous small Nuremberger Bratwurst), Schäuferla (roast pork shoulder), Sauerbraten, dumplings, potato salad (typically made with broth), fried carp, Grupfder (seasoned cheese spread), Presssack (a type of Head cheese: pressed or jellied pork trimmings, like tongue, cheeks, etc.). Lebkuchen are a traditional type of biscuit, and Küchla is a sort of sweet fried dough.

Three Nuremberger Bratwürste in a roll (Drei im Weckla)

Three Nuremberger Bratwürste in a roll (Drei im Weckla) Schlenkerla Rauchbier straight from the cask

Schlenkerla Rauchbier straight from the cask Franconian wine is traditionally filled up in Bocksbeutels

Franconian wine is traditionally filled up in Bocksbeutels Fried Carp with beer and salad

Fried Carp with beer and salad

Tourism

The tourism industry stresses the romantic character of Franconia.[138][139] Arguments for this include the picturesque countryside and the many historic buildings that present the long history and culture of the region.,[139] In addition, the relatively few industrial towns outside of the main industrial cities is underlined. Franconian wine, the rich tradition of beer brewing and local culinary specialities, such as Lebküchnerei or gingerbread baking, are also seen as a draw that is worth marketing,[139][140] and which make Franconia a popular tourist destination in Germany. The Romantic Road, the best known German theme route, links several of the tourist high points in western Franconia.[141] The Castle Road runs through the whole Franconian region with its numerous castles and other medieval structures.

The Franconian countryside is suitable for many sporting activities. For example, the Franconian Way, Celtic Way and the hiking trail network of the Altmühl Valley and the Central Uplands offer a lot of hiking options.

Cycling along the large rivers is very popular, for example along the Main Cycleway, which was the first German long distance cycleway to be awarded five starts by the Allgemeiner Deutscher Fahrrad-Club (ADFC). The Tauber Valley Cycleway, a 101 kilometre-long cycle trail in Tauber Franconia, was the second German long distance cycleway to receive five stars.[142]

In the Fichtel Mountains and the Franconian Forest, many tourists come for making hiking tours. In winter people can do skiing f. e. on the Ochsenkopf. Very popular are raftings on the Wild Rodach in Wallenfels in the Franconian Forest.

Notes

- East Franconia should not be confused with the eastern division of the Frankish Empire, East Francia, which was also known as Francia Orientalis in Latin. This refers to the much larger area which later became the German Kingdom and of which the whole of the Duchy of Franconia was a part.

References

Footnotes

- Alfred Klepsch: Fränkische Dialekte. In: Historisches Lexikon Bayerns

- Karten zur Geschichte Bayerns: Jutta Schumann / Dieter J. Weiß, in: Edel und Frei. Franken im Mittelalter, ed. by Wolfgang Jahn / Jutta Schumann / Evamaria Brockhoff, Augsburg, 2004 (Veröffentlichungen zur Bayerischen Geschichte und Kultur 47/04), pp. 174–176, Cat. No. 51. Siehe Haus der Bayerischen Geschichte

- Rudolf Endres: "Der Fränkische Reichskreis". In: Hefte zur Bayerischen Geschichte und Kultur 29, published by the Haus der Bayerischen Geschichte, Regensburg, 2003, p. 6, see online version (PDF).

- Manfred Treml: "Das Königreich Bayern (1806–1918)". In: Politische Geschichte Bayerns, published by the Haus der Bayerischen Geschichte as Issue 9 of the Hefte zur Bayerischen Geschichte und Kultur, 1989, pp. 22–25, here: p. 22.

- Entry Franken in the Deutsches Wörterbuch. Boris Paraschkewow: Wörter und Namen gleicher Herkunft und Struktur. Lexikon etymologischer Dubletten im Deutschen. Berlin, 2004, p. 107

- Ulrich Nonn: Die Franken. Stuttgart, 2010, pp. 11–14 ff.

- Friedrich Helmer: Bayern im Frankenreich (5.–10. Jahrhundert). In: Politische Geschichte Bayerns, herausgegeben vom Haus der Bayerischen Geschichte als Heft 9 der Hefte zur Bayerischen Geschichte und Kultur, pp. 4–6, here: p. 4

- Rudolf Endres: Der Fränkische Reichskreis. In: Hefte zur Bayerischen Geschichte und Kultur 29, published by the House of Bavarian History, Regensburg, 2003, p. 37, see online version Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine (pdf)

- Was ist fränkisch? Wie eine Region definiert wird, Bayerischer Rundfunk, Bayern 2

- Sprachatlas der BLO Archived 2012-07-02 at WebCite, retrieved 1 July 2014.

- Ulrich Maier (Justinus-Kerner-Gymnasium Weinsberg): Schwäbisch oder fränkisch? Mundart im Raum Heilbronn Bausteine zu einer Unterrichtseinheit. see online pdf Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine

- "Ominöses Frankenbewusstsein", Süddeutsche Zeitung dated 10 February 2013, retrieved 5 May 2016.

- Dreifrankenstein Archived 2016-03-22 at the Wayback Machine, retrieved 12 July 2014.

- Source: the BfN map

- Sandwege Archived 2016-06-29 at the Wayback Machine, Sandachse Franken, retrieved 23 May 2014

- Naturpark Bayerische Rhön Archived 2016-07-29 at the Wayback Machine, retrieved 2 Jun 2014.

- "www.br-online.de: Bund Naturschutz zu Steigerwald – "Imagegewinn durch Nationalpark"". Archived from the original on July 21, 2012. Retrieved 2017-03-29.CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) Press report on the rejected Steigerwald National Park at BR-online, Studio-Franken

- Wir über uns Archived 2016-07-03 at the Wayback Machine, www.naturpark.de, retrieved 28 May 2014.

- Naturparks in Franken Archived 2016-07-30 at the Wayback Machine, retrieved 2 June 2014.

- Biosphärenreservat Rhön Archived 2016-04-19 at the Wayback Machine, Bayerisches Staatsministerium für Umwelt und Verbraucherschutz, retrieved 28 May 2014.

- Bayerns schönste Geotope, Bayerisches Staatsministerium für Umwelt und Verbraucherschutz, retrieved 28 May 2014.

- Karte der Vogelschutzgebiete Archived 2016-06-17 at the Wayback Machine: Mittelfranken, stellvertretend für alle Europäischen Vogelschutzgebieten in Franken

- Fichtelgebirge Nature Park Archived 2016-06-11 at the Wayback Machine, retrieved 2 Jun 2014.

- Wildlife in Bavaria: The wolf - a Native Bavarian Archived 2016-04-22 at the Wayback Machine, Bayerischer Rundfunk, retrieved 16 August 2014.

- Stefan Glaser, Gerhard Doppler and Klaus fword (eds.): GeoBavaria. 600 Millionen Jahre Bayern. Internationale Edition. Bayerisches Geologisches Landesamt, Munich, 2004 (online Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine), p. 4

- Stefan Glaser, Gerhard Doppler and Klaus fword. (eds.): GeoBavaria. 600 Millionen Jahre Bayern. Internationale Edition. Bayerisches Geologisches Landesamt, Munich, 2004 (online Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine), p. 24

- Alfons Baier, Thomas Hochsieder: Zur Stratigraphie und Tektonik des SE-Randes der Münchberger Gneismasse (Oberfranken) Archived 2016-09-07 at the Wayback Machine. Website of the University of Erlangen-Nuremberg with a summary of the essay of the same name in the Geologischen Blättern für Nordost-Bayern, Vol. 39, No. 3/4, Erlangen, 1989

- Stefan Glaser, Gerhard Doppler and Klaus Schwerd (eds.): GeoBavaria. 600 million years Bavaria. International Edition. GeoBavaria. 600 Millionen Jahre Bayern. Internationale Edition. Bayerisches Geologisches Landesamt, Munich, 2004 (online Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine), p. 26

- Dickinson, Robert E (1964). Germany: A regional and economic geography (2nd ed.). London: Methuen, p 568. .

- Walter Freudenberger: Tektonik: Deckgebirge nördlich der Donau. In: Walter Freudenberger, Klaus Schwerd (Red.): Erläuterungen zur Geologischen Karte von Bayern 1:500 000. Bayerisches Geologisches Landesamt, Munich, 1996 (online Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine), p. 259-265

- Stefan Glaser, Gerhard Doppler and Klaus Schwerde. (eds.): Stefan Glaser, Gerhard Doppler und Klaus Schwerd (Red.): GeoBavaria. 600 Millionen Jahre Bayern. Internationale Edition. Bayerisches Geologisches Landesamt, Munich, 2004 (online Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine), p. 40 ff.

- Hans-Georg Herbig, Thomas Wotte, Stefanie Becker: First proof of archaeocyathid-bearing Lower Cambrian in the Franconian Forest (Saxothuringian Zone, Northeast Bavaria). In: Jiři Žák, Gernold Zulauf, Heinz-Gerd Röhling (Hrsg.): Crustal evolution and geodynamic processes in Central Europe. Proceedings of the Joint conference of the Czech and German geological societies held in Plzeň (Pilsen), September 16–19, 2013. Schriftenreihe der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Geowissenschaften. No. 82, 2013, p. 50 (full text: Researchgate)

- Hartmut Haubold: Die Saurierfährten Chirotherium barthii Kaup, 1835 - das Typusmaterial aus dem Buntsandstein bei Hildburghausen/Thüringen und das "Chirotherium-Monument". Publication by the Natural History Museum, Schleusingen, vol. 21, 2006, pp. 3–31

- Frank-Otto Haderer, Georges Demathieu, Ronald Böttcher: Wirbeltier-Fährten aus dem Rötquarzit (Oberer Buntsandstein, Mittlere Trias) von Hardheim bei Wertheim/Main (Süddeutschland). Stuttgarter Beiträge zur Naturkunde, Serie B. No. 230, 1995, online Archived 2017-09-29 at the Wayback Machine

- Laura K. Säilä: The Osteology and Affinities of Anomoiodon liliensterni, a Procolophonid Reptile from the Lower Triassic Buntsandstein of Germany. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. Vol. 28, No. 4, 2008, pp. 1199–1205, doi:10.1671/0272-4634-28.4.1199

- Friedrich von Huene: Ueber die Procolophoniden, mit einer neuen Form aus dem Buntsandstein. Centralblatt für Mineralogie, Geologie und Paläontologie. 1911 issue, 1911, pp. 78–83

- Rainer R. Schoch: Comparative osteology of Mastodonsaurus giganteus (Jaeger, 1828) from the Middle Triassic (Lettenkeuper: Longobardian) of Germany (Baden-Württemberg, Bayern, Thüringen). Stuttgarter Beiträge zur Naturkunde, Series B. No. 278, 1999, pp. 21 and 27 (PDF 3,6 MB)

- Emily J. Rayfield, Paul M. Barrett, Andrew R. Milner: Utility and Validity of Middle and Late Triassic 'Land Vertebrate Faunachrons'. In: Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. Vol. 29, 2009, No. 1, pp. 80–87, doi:10.1671/039.029.0132.

- Olivier Rieppel: The genus Placodus: Systematics, Morphology, Paleobiogeography, and Paleobiology. Fieldiana Geology, New Series, No. 31, 1995, doi:10.5962/bhl.title.3301.

- Olivier Rieppel, Rupert Wild. A Revision of the Genus Nothosaurus (Reptilia: Sauropterygia) from the Germanic Triassic, with Comments on the Status of Conchiosaurus clavatus. Fieldiana Geology, New Series, No. 34, 1996. doi:10.5962/bhl.title.2691

- Markus Moser: Plateosaurus engelhardti MEYER, 1837 (Dinosauria: Sauropodomorpha) aus dem Feuerletten (Mittelkeuper; Obertrias) von Bayern. Zitteliana, Series B: Treatises of the Bavarian State Collection for Palaeontology and Geology. Vol. 24, 2003, pp. 3-186, urn:nbn:de:bvb:19-epub-12711-3

- Birgit Niebuhr: Wer hat hier gelogen? Die Würzburger Lügenstein-Affaire. Fossilien. No. 1/2006, 2006, S. 15–19 ("PDF" (PDF). Archived from the original on September 13, 2014. Retrieved 2016-01-11.CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) 886 kB)

- Mittelwerte und Kenntage der Lufttemperatur, Bayerisches Landesamt für Umwelt, retrieved 23 May 2014.

- Neue Daten für alle Regionen: Deutschlands wahres Klima, Spiegel Online, retrieved 23 May 2014

- Mittelwerte des Gebietsniederschlags, www.lfu.bayern.de, Bayerisches Landesamt für Umwelt, retrieved 23 May 2014.

- "mercer.de". Archived from the original on 2012-01-18. Retrieved 2016-07-23.

- Landkreis Eichstätt ist die lebenswerteste Region Deutschlands, Focus Online, retrieved 10 September 2014

- Deutsche Post Glücksatlas Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine, retrieved 10 September 2014.

- Glücksatlas 2013: Franken sind so unglücklich wie nie zuvor Archived 2016-09-17 at the Wayback Machine. Nordbayern.de, published 5 November 2013, retrieved 10 September 2014.

- Geschiedenis van het Nederlands by M van der Wal, 1992

- Gerhard Köbler, Historisches Lexikon der deutschen Länder, Darmstadt 1999, pp. 173–174

- Gerhard Köbler, Historisches Lexikon der deutschen Länder, Darmstadt 1999

- Die Höhlenruine von Hunas Archived 2016-03-06 at the Wayback Machine, Archäologisches Lexikon, retrieved 17 June 2014.

- Hans-Peter Uenze, Claus-Michael Hüssen: Vor- und Frühgeschichte. In: Handbuch der Bayerischen Geschichte, begr. von Max Spindler, 3rd vol., 1st sub-vol.: Geschichte Frankens bis zum Ausgang des 18. Jahrhunderts, re-published by Andreas Kraus, 3rd, revised edition, Munich, 1997, pp. 3–46, here: pp. 17ff.

- Josef Motschmann: Altenkunstadt - Heimat zwischen Kordigast und Main. Gemeinde Altenkunstadt, Altenkunstadt, 2006, p. 10

- Peter Kolb, Ernst-Günter Krenig: Unterfränkische Geschichte. Von der germanischen Landnahme bis zum hohen Mittelalter., Vol. 1. Würzburg, 1989; second edition: 1990, pp. 27–37.

- Wilfried Menghin: Grundlegung: Das frühe Mittelalter. In: Handbuch der Bayerischen Geschichte, begr. von Max Spindler, 3rd vol., 1st sub-vol.: Geschichte Frankens bis zum Ausgang des 18. Jahrhunderts, re-published by Andreas Kraus, 3rd, revised edition, Munich, 1997, pp. 47–69, here: p. 60

- Wilfried Menghin: Grundlegung: Das frühe Mittelalter. In: Handbuch der Bayerischen Geschichte, begr. von Max Spindler, 3. Bd., 1. Teilbd: Geschichte Frankens bis zum Ausgang des 18. Jahrhunderts, re-published by Andreas Kraus, 3rd, revised edition, Munich, 1997, pp. 47–69, here: S. 55.

- Franz-Joseph Schmale, Wilhelm Störmer: Die politische Entwicklung bis zur Eingliederung ins Merowingische Frankenreich. In: Handbuch der Bayerischen Geschichte, begr. von Max Spindler, 3rd vol., 1st sub-vol.: Geschichte Frankens bis zum Ausgang des 18. Jahrhunderts, re-published by Andreas Kraus, 3rd, revised edition, Munich, 1997, pp. 89–114, here: p. 80.

- Friedrich Helmer: Bayern im Frankenreich (5. - 10. Jahrhundert), In: Politische Geschichte Bayerns, published by the Haus der Bayerischen Geschichte as Issue 9 of the Hefte zur Bayerischen Geschichte und Kultur, pp. 4–6, here: p. 6

- Josef Kirmeier: Bayern und das Deutsche Reich (10.-12. Jahrhundert), In: Politische Geschichte Bayerns, published by the Haus der Bayerischen Geschichte as Issue 9 of the Hefte zur Bayerischen Geschichte und Kultur, pp. 7–9, here: p. 7

- Karten zur Geschichte Bayerns: Jutta Schumann / Dieter J. Weiß, in: Edel und Frei. Franken im Mittelalter, ed. by Wolfgang Jahn / Jutta Schumann / Evamaria Brockhoff, Augsburg, 2004 (Veröffentlichungen zur Bayerischen Geschichte und Kultur 47/04), pp. 174–176, Cat. No. 51. See Haus der Bayerischen Geschichte Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine

- Dieter Weiß: Bamberg, Hochstift: Territorium und Struktur. In: Historisches Lexikon Bayerns

- Meininger Urkundenbuch Nos. 3-5. Reg. Thur. I Nos. 614, 616, 618-. Stadtarchiv Meiningen.

- Otto Spälter: Nürnberg, Burggrafschaft. In: Historisches Lexikon Bayerns

- Alois Gerlich, Franz Machilek: Die innere Entwicklung vom Interregnum bis 1800: Staat, Gesellschaft, Kirche Wirtschaft. - Staat und Gesellschaft. Erster Teil: bis 1500 In: Handbuch der Bayerischen Geschichte, begr. von Max Spindler, 3rd vol., 1st sub-vol.: Geschichte Frankens bis zum Ausgang des 18. Jahrhunderts, re-published by Andreas Kraus, 3rd, revised edition, Munich, 1997, pp. 537–701, here: p. 602.

- Alexander Schubert: Swabian League of Cities. In: Historisches Lexikon Bayerns

- Rudolf Endres: Staat und Gesellschaft. Zweiter Teil: 1500-1800. In: Handbuch der Bayerischen Geschichte, begr. von Max Spindler, 3rd vol., 1st sub-vol.: Geschichte Frankens bis zum Ausgang des 18. Jahrhunderts, re-published by Andreas Kraus, 3rd, revised edition, Munich, 1997, pp. 702–781, here: pp. 752ff

- Wilhelm Störmer: Die innere Entwicklung: Staat, Gesellschaft, Kirche, Wirtschaft. In: Handbuch der Bayerischen Geschichte, begr. von Max Spindler, 3rd vol., 1st sub-vol.: Geschichte Frankens bis zum Ausgang des 18. Jahrhunderts, re-published by Andreas Kraus, 3rd revised edition, Munich, 1997, pp. 210–315, here: p. 314.

- Johannes Merz: Herzogswürde, fränkische. In: Historisches Lexikon Bayerns

- Rudolf Endres: Der Fränkische Reichskreis, In: Hefte zur Bayerischen Geschichte und Kultur 29, published by the Haus der Bayerischen Geschichte, Regensburg, 2003, p. 21, see online version (pdf)

- Michael Henker: Bayern im Zeitalter von Reformation und Gegenreformation (16./17. Jahrhundert), In: Politische Geschichte Bayerns, published by the Haus der Bayerischen Geschichte as Issue 9 of the Hefte zur Bayerischen Geschichte und Kultur, pp. 14–17, here: p. 14

- Pütter, John Stephen. An Historical Development of the Present Political Constitution of the Germanic Empire, Vol. 3, London: Payne, 1790, p. 156.

- Rudolf Endres: Von der Bildung des Fränkischen Reichskreises und dem Beginn der Reformation bis zum Augsburger Religionsfrieden von 1555. In: Handbuch der Bayerischen Geschichte, edited by Max Spindler, 3rd vol., 1st sub-vol.: Geschichte Frankens bis zum Ausgang des 18. Jahrhunderts, re-published by Andreas Kraus, 3rd revised edition, Munich, 1997, pp. 451–472, here: pp. 455ff.

- Endter-Bibeln Archived 2016-06-11 at the Wayback Machine, Württembergische Landesbibliothek, retrieved 5 July 2014.

- Rudolf Endres: Von der Bildung des Fränkischen Reichskreises und dem Beginn der Reformation bis zum Augsburger Religionsfrieden von 1555. In: Handbuch der Bayerischen Geschichte, edited by Max Spindler, 3rd vol., 1st sub-vol.: Geschichte Frankens bis zum Ausgang des 18. Jahrhunderts, re-published by Andreas Kraus, 3rd revised edition, Munich, 1997, pp. 451–472, here: p. 467.

- Birke Grießhammer: Verfolgt – gefoltert – verbrannt. Die Opfer des Hexenwahns in Franken., pp. 15 ff

- Christian Hege: Königsberg in Bayern (Freistaat Bayern, Germany). In: Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online

- Christian Neff: Nürnberg (Freistaat Bayern, Germany). In: Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online

- Stadthistorische Streiflichter (24), www.wuerzburg.de, accessed 7 June 2014.

- Rudolf Endres: Von der Bildung des Fränkischen Reichskreises und dem Beginn der Reformation bis zum Augsburger Religionsfrieden von 1555. In: Handbuch der Bayerischen Geschichte, ed. Max Spindler, 3 vols., 1 sub-vol: History of Franconia to the end of the 18th century, revised by Andreas Kraus, 3rd revised edition, Munich, 1997, pp. 451-472, here: p. 469

- Michael Henker: Bayern im Zeitalter von Reformation und Gegenreformation (16./17. Jahrhundert), In: Politische Geschichte Bayerns, published by the House of Bavarian History as Issue 9 of the Hefte zur Bayerischen Geschichte und Kultur, pp. 14–17, here: p. 15

- Rudolf Endres. Der Fränkische Reichskreis, In: Hefte zur Bayerischen Geschichte und Kultur 29, published by the House of Bavarian History, Regensburg, 2003, p. 19, see online version (pdf)

- Rudolf Endres: Vom Augsburger Religionsfrieden bis zum Dreißigjährigen Krieg. In: Handbuch der Bayerischen Geschichte, ed. Max Spindler, 3rd vol., 1st sub-vol: Geschichte Frankens bis zum Ausgang des 18. Jahrhunderts, revised by Andreas Kraus, 3rd revised edn., Munich, 1997, pp. 473–495, here: p. 490.

- Michael Henker: Bayern im Zeitalter von Reformation und Gegenreformation (16./17. Jahrhundert), In: Politische Geschichte Bayerns, published by the House of Bavarian History as Issue 9 of the Hefte zur Bayerischen Geschichte und Kultur, pp. 14–17, here: p. 17

- Aus Österreich vertrieben: Glaubensflüchtlinge in Franken, br.de, Bayerischer Rundfunk, retrieved 7 June 2014.

- Karlheinz Scherr: Bayern im Zeitalter des Fürstlichen Absolutismus (17./18. Jahrhundert), In: Politische Geschichte Bayerns, published by the House of Bavarian History as Issue 9 of the Hefte zur Bayerischen Geschichte und Kultur, pp. 18–21, here: p. 20

- Rudolf Endres: Der Fränkische Reichskreis, In: Hefte zur Bayerischen Geschichte und Kultur 29, published by the House of Bavarian History, Regensburg, 2003, p. 35, see online version Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine (pdf)

- Rudolf Endres: Der Fränkische Reichskreis, In: Hefte zur Bayerischen Geschichte und Kultur 29, published by the house of Bavarian History, Regensburg, 2003, p. 38, see online version Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine (pdf)

- Preußen in Franken 1792 - 1806 Archived 2016-11-16 at the Wayback Machine, material from the State Exhibition in 1999 by the House of Bavarian History

- Der Friede von Lunéville (1801) und der Reichsdeputationshauptschluss (1803), House of Bavarian History, accessed 7 June 2014.

- Rheinbundakte, deutsche Fassung (1806), House of Bavarian History , retrieved 7 June 2014.

- Dietmar Willoweit: Reich und Staat: Eine kleine deutsche Verfassungsgeschichte, p. 70