Frans Floris

Frans Floris, Frans Floris the Elder or Frans Floris de Vriendt (17 April 1519 – 1 October 1570)[1] was a Flemish painter, draughtsman, print artist and tapestry designer. He is mainly known for his history paintings, allegorical scenes and portraits.[2] He played an important role in the movement in Northern Renaissance painting referred to as Romanism. The Romanists had typically travelled to Italy to study the works of leading Italian High Renaissance artists such as Michelangelo, Raphael and their followers. Their art assimilated these Italian influences into the Northern painting tradition.[3][4]

_-_Self-portrait.jpg.webp)

Life

Frans Floris was born in Antwerp. He was the scion of a prominent artist family which originally went with the name ‘de Vriendt’. The earliest known ancestors of the Floris de Vriendt family, then still called only ‘de Vriendt’, were residents of Brussels where they practiced the craft of stonemason and stonecutter which was passed on from father to son. One of Frans' ancestors became in 1406 a master of the Brussels stonemasons guild. A family member, Jan Florisz. de Vriendt, left his native Brussels and settled in Antwerp in the mid-15th century. His patronymic name ‘Floris’ became the common family name in subsequent generations. The original form ‘de Vriendt’ can, however, still be found in official documents until the late 16th century.[5]

Frans' brothers were prominent artists. The most famous one is Cornelis who was an architect and sculptor and was one of the designers of the Antwerp City Hall. Jacob Floris was a painter of stained-glass windows and Jan Floris was a potter.[5] Jan traveled to Spain to practice his art there and died young.

Documentary evidence about the life of Frans Floris is scarce. Most of what we know about the youth and training of Frans Floris is based on the early biographer Karel van Mander's biography of the artist. At ten pages long it is one of the most detailed biographies in van Mander's Het Schilder-boeck published in 1604. According to van Mander, Frans Floris was the son of the stonecutter Cornelis I de Vriendt (died 1538). Like his brothers, Frans began as a student of sculpture, but later he gave up sculpture for painting. Floris went to Liège where he studied with the prominent painter Lambert Lombard. The choice for Lombard as a teacher was surprising since Antwerp was a cultural centre with many outstanding painters. He may have chosen Lombard as his brother Cornelis was good friends with Lombard, whom he had met in Rome around 1538. It is also possible that Frans trained as a painter in Antwerp before studying under Lombard. Floris became a master in the Antwerp Guild of Saint Luke in 1539–40.[4]

Lombard encouraged Frans Floris to study in Italy. He traveled to Rome probably as early as 1541 or 1542 and became fascinated with Italian contemporary painting (particularly Michelangelo and Raphael) and the Classical sculpture and art of Rome. He kept a notebook of sketches, which his pupils would later etch. Floris visited other cities in Italy including Mantua and Genoa.[4]

Upon his return to Antwerp around 1545, Frans Floris opened a workshop on the Italian model.[4] He became the leading history painter and was called the ‘Flemish Raphael’. He enjoyed the patronage of prominent personalities such as the wealthy Antwerp banker Niclaes Jonghelinck for whose house he painted a series of ten compositions on the legend of Hercules and seven compositions on the liberal arts. He also painted 14 large panels for the duke of Aarschot's palace of Beaumont. Local nobility including the knights of the Golden Fleece, the Prince of Orange and the Counts of Egmont and Horn (later the leaders of the Dutch Revolt) visited Floris at his home, attracted by his artistic reputation as well as his ability to talk with ‘great insight and judgment on any topic’.[6] He also moved in the circle of the leading humanists such as Abraham Ortelius, Christophe Plantin, Lucas de Heere, Lambert Lombard, Dominicus Lampsonius and Hieronymus Cock. This group of intellectuals and artists was the first to develop theories on art and the role of artists in the Low Countries.[7] In 1549 Floris was commissioned by the Antwerp city authorities to design the decorations for the Joyous entry into Antwerp of Charles V of Spain and the Infante Philip.[4]

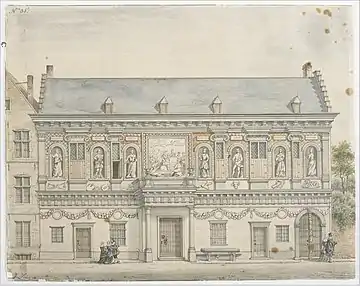

His brother Cornelis designed a palace for him in Antwerp with a façade of blue limestone and with luxurious decorations such as gilded leather wall-coverings in the bedroom.[8] The façade itself was designed by Frans. His design program for the façade was intended to illustrate the high status of artists in society. He painted the façade with seven personifications symbolizing the qualities and skills of an artist: Accuracy (Diligentia), Practice (Usus), Labor (Labor), Diligence (Industria), Experience (Experientia), Praise (Lauda) and Architecture (Architectura). Above the doorway of the house a relief depicted the sciences (the seven liberal arts together with painting and architectures) as the principal components of human society. The unknown monogrammist TG portrayed the façade in 1576 in a print.[9] Jozef Linnig made a drawing of the palace in the 19th century but by that time most of the decoration of the façade had disappeared. Floris expressed similar ideas in his composition The awakening of the Arts (Museo de Arte de Ponce).[10]

In 1547 Floris married Clara Boudewijns and the couple had one daughter and two sons. The sons Frans and Baptist were later trained as artists by their father. Baptist died young while Frans moved to Italy where he had a successful career.[6]

Frans Floris was known to be hardworking as is testified by his motto: Als ick werck, dan leef ick: als ick spelen gae, dan sterf ick. This means "When I work, I live: when I play, I die." Van Mander recounts that Floris nearly always had a large commission in his workshop on which he would work late at night, and that when he dozed off his pupils would take off his shoes and stockings and put him to bed before they left. Van Mander cites Frans Menton who asserted Floris was loved by his pupils for allowing them more freedom than other Antwerp masters. When a small group of his pupils met up for a reunion after his death they were able to compile a list of 120 of his pupils.[11]

Van Mander recounts that at the end of his life Floris became heavily indebted and started drinking.[8] The debts were likely related to his high costs of living as well as the impact of the Beeldenstorm or Iconoclastic Fury that commenced from the 1560s and reached its peak in 1566. During the period of iconoclasm, Catholic art and many forms of church fittings and decoration were destroyed by nominally Calvinist Protestant crowds as part of the Protestant Reformation. It is said Floris never recovered from the shock of seeing his artworks destroyed. Instead, he found himself in a downward spiral in both his personal and professional affairs. His disaffection was so great that he even refused to restore his own works damaged during the Beeldenstorm. He virtually stopped painting after 1566 and his place as the leading history painter in the Habsburg Netherlands was taken by a younger generation of artists among whom Marten de Vos became the most prominent.[12]

Van Mander recounts that while working on a large commission for the grand prior of Spain, Floris became ill and died on 1 October 1570 in Antwerp. His paintings for the grand prior were finished by his studio assistants Frans Pourbus the Elder and Chrispijn van den Broeck. Poems were written about him by Dominicus Lampsonius and the poet-painter Lucas de Heere, who according to van Mander, was his pupil.[8]

Pupils

The Netherlands Institute for Art History identifies the following pupils of Frans Floris: Joos de Beer (later the teacher of Abraham Bloemaert), George Boba, Hendrick van den Broeck, Marten van Cleve, Ambrosius Francken, Frans Francken I, Frans Menton (known for schutterstukken in Alkmaar), and Isaac Claesz van Swanenburg.[2] Van Mander lists 26 pupils of Floris, but he may have had as many as 120 assistants. Van Mander's list includes Chrispijn van den Broeck, Joris van Ghent (who served Philip II of Spain), Marten (and his brother Hendrick) van Cleve, Lucas de Heere, Anthonie Blocklandt van Montfoort, Thomas van Zirickzee, Simon van Amsterdam, Isaac Claesz van Swanenburg (spelled Isaack Claessen Cloeck), Frans Menton, George Boba, the three Francken brothers Jeroen, Frans and Ambrosius, Joos de Beer, Hans de Maier van Herentals, Apert Francen van Delft, Lois van Brussel, Thomas van Coelen, Hans Daelmans van Antwerpen, Evert van Amersfoort, Herman van der Mast, Damiaen van der Goude, Jeroen van Vissenaken, Steven Croonenborgh uyt den Hage, and Dirck Verlaen van Haerlem.[8]

The long list of pupils and assistants shows that Frans Floris had upon his return to Antwerp adopted the studio practices that he had witnessed in Italy. He relied on a large number of assistants who came from all over the southern and northern Netherlands and even Germany. Floris invented and developed the use of study heads, which were life-size representations of people's heads, which he painted in oil on panel. These were then given to his assistants, either for literal transcription or for freer adaptations. His assistants' role is not always clear and may have ranged from painting after his study heads to adding landscape backgrounds. They also copied his compositions, either in paint or on paper, for reproduction by engravers.[4]

Work

General

Comparatively few of his works have survived, possibly because many were destroyed during the iconoclastic destructions in Antwerp in the second half of the sixteenth century. The earliest extant canvas by Floris is the Mars and Venus ensnared by Vulcan in the Gemäldegalerie, Berlin (1547).

Frans Floris is mainly known for his altarpieces, compositions with mythological and allegorical themes and to a lesser extent, for his portraits. He played an important role in introducing the genre of mythological and allegorical subject-matter into Flanders. He was one of the first Netherlandish artists to travel to Italy and study the latest developments in art as well as the Classical relics of Rome. The principal contemporary influences were Michelangelo from whom he borrowed the heroic treatment of the nude and Raphael whom he emulated by developing a ‘relief-like’ idiom. Floris did, however, not abandon the traditional Netherlandish technique of oil paint, which allowed him to fuse its detailed, descriptive properties with his radically new visual language, in which embellishments were reduced to a minimum and the nude played a prominent role.[13]

Floris’ early work of around 1545 shows most clearly the influence of his Italian sojourn. It shows similarities with the work of other Romanists such as Lambert Lombard and Pieter Coecke van Aelst. Later his style became increasingly monumental. His compositional skills improved in that he showed more skill in the arrangement of the figures. After 1560 his work became more Mannerist and the sculptural handling of the figures gave way to a more painterly approach. His palette evolved towards the monochrome. Later he may have been influenced by the school of Fontainebleau as his figures became more elegant and the works more refined.[5]

Just like his brother Cornelis was able to exert influence on contemporary architecture across the borders of Flanders through the medium of the Antwerp publishers, Floris’ work found wide circulation through engravings made by the leading Antwerp engravers.[5][14] Hieronymus Cock, Philip Galle and Cornelis Cort were the principal engravers involved in this effort but others such as Johannes Wierix, Balthazar van den Bos, Pieter van der Heyden, Frans Huys, Dirck Volckertsz. Coornhert and Jan Sadeler I also made engravings after the works of Frans Floris. Floris also made original designs for series of prints engraved in Antwerp.[5]

Portraits

He was a very skilled portraitist but, possibly because of the lower ranking of portraiture in the hierarchy of pictorial genres, he painted only a few (possibly about 12) portraits. He is still regarded as an innovator of the genre as he introduced a new level of expressiveness and accentuated psychological presence. Floris pioneered two types of images in the late 1540s: expressive portraits of individual sitters and head studies on panels. By 1562, Floris’ distinctive head studies had become a form of authorial performance, which bore witness to his creative genius and the workshop practices that he had imported from Italy. While the head studies were made for his own use as well as for the pupils and assistants in his workshop, some were clearly also produced as artworks in their own right. The rapid, expressive brushwork of these panels suggests that he painted some heads as creative studies and thus anticipate in a certain way the tronies of 17th-century artists. These studies became collector's items for local art lovers. The head studies testify to the self-conscious artistic culture of Antwerp, where they were valued for their authorship rather than their preparatory value.[15]

Frans Floris made a self-portrait, the original of which has been lost and which is known through a copy in the Kunsthistorisches Museum. He included self-portraits in some of his religious works such as the composition Rijckart Aertsz as Saint Luke in which he included himself as the pigment grinder and in the composition Allegory of the Trinity (Louvre) where beneath Christ's outstretched right arm he painted his self-portrait, which appears out of scale with the other heads around him. The inclusion of his portrait in the latter composition suggests that the painting held a highly personal meaning for the artist. It has been observed that after the iconoclasm of the Beeldenstorm Flemish artists started including their portraits in religious compositions in order to show their personal commitment to the particular message that the compositions were trying to convey.[16]

Floris painted some family portraits. An example is the Family portrait in the Museum Wuyts-Van Campen en Baron Caroly, Lier, which is dated 1561. It was traditionally believed to depict the Berchem family, a prominent family. However, this is no longer accepted unanimously. The painting has two inscriptions, one in the painting itself, the other on its original frame. The first inscription appears on a portrait hanging on the wall behind the figures. It states that the man depicted in the portrait died on 10 January 1559, aged 58 years. The second is the Latin text written at the top and bottom of the frame of the painting. It translates as follows: "As in life there can be nothing happier than a marriage in unison and a bed without discord, there is nothing more pleasant than to see one's offspring in unison enjoy peace with an immaculate mind, 1561”. The painting thus simultaneously served as a memento of the deceased father and an expression of the feelings of togetherness of his descendants. Floris depicts all the members of the family performing and attending a concert of music, which emphasized this notion of 'concordia', i.e. the harmony within the family.[17]

References

- "Frans Floris the Elder (1519–1570)". Royal Academy.

- Frans Floris at the Netherlands Institute for Art History

- Ilja M. Veldman. "Romanism." Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. Oxford University Press. Web. 26 March 2015

- Carl Van de Velde. "Frans Floris I." Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. Oxford University Press. Web. 26 March 2015

- Carl Van de Velde. "Floris." Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. Oxford University Press. Web. 26 March 2015

- Frans Jozef van den Branden, Geschiedenis der Antwerpsche Schilderschool, Antwerp: J.-E. Buschmann, 1883

- Jeroen Vandommele, p. 255

- Frans Floris in Karel van Mander, Het Schilderboeck, 1604 (in Dutch)

- Jeroen Vandommele, p. 263-265

- Jozef Linnig, The house of Frans Floris at Musea en Erfgoed Antwerpen (in Dutch)

- Isaack Claessen Cloeck, in Frans Floris biography in Karel van Mander's Schilderboeck, 1604 (in Dutch)

- Edward H. Wouk, pp. 61–62

- Edward H. Wouk, p. 43

- Carl Van de Velde. "Cornelis Floris II."] Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. Oxford University Press. Web. 26 March 2015

- Edward H. Wouk, p. 45-46

- Edward H. Wouk, p. 41-44

- Van de Velde Carl, 'Frans Floris, De familie van Berchem' at Openbaar Kunstbezit Vlaanderen

Sources

- Jeroen Vandommele, 'Als in een spiegel, Vrede, kennis en gemeenschap op het Antwerpse Landjuweel van 1561', Hilversum (in Dutch)

- Edward H. Wouk, Frans Floris’s Allegory of the Trinity (1562) and the Limits of Tolerance, Art History 10/2014; 38(1), p. 39-76

Further reading

- Liedtke , Walter A. (1984). Flemish paintings in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 0870993569. (see index: Floris, Frans I).

- Ger Luijten "Frans Floris, Volume 21 of The new Hollstein Dutch & Flemish etchings, engravings and woodcuts, 1450-1700", Sound & Vision, 2011

External links

Media related to Paintings by Frans Floris the Elder at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Paintings by Frans Floris the Elder at Wikimedia Commons