G.I. movement

The term G.I. movement refers to resistance to military involvement in the Vietnam War from active duty soldiers in the United States military.[1][2][3] Within the military popular forms of resistance included combat refusals, fragging, and desertion. By the end of the war at least 600 officers were killed in fraggings, over 300 refused to combat[4] and approximately 50,000 American servicemen deserted.[5] Along with resistance inside the U.S. military, civilians opened up various GI Coffeehouses near military bases where civilians could meet with soldiers and could discuss and cooperate in the anti-war movement.[3]

| G.I. movement | |

|---|---|

| Part of the Opposition to U.S. involvement in Vietnam | |

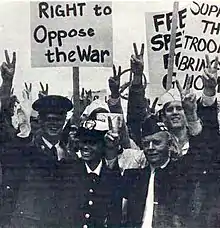

Propaganda from the GI movement, taken from the book A Matter of Conscience. | |

| Date | 1964–1973 |

| Caused by | United States Involvement in the Vietnam War |

| Goals | Avoid military duties in the Vietnam War |

| Methods |

|

| Resulted in |

|

History

Early movement (1964-1967)

The early period of soldier resistance to the Vietnam War involved mainly individual acts of resistance. Some well publicized incidents occurred in this period. The first incident was in November 1965 when Lt. Henry H. Howe, Jr was court marshaled for shouting anti-war slogans during a protest in El Paso. Another in 1966 was a case where three soldiers in Fort Hood refused deployment to Vietnam and were reprimanded, gaining the attention of anti-war activists. Later Capt. Howard Levy a dermatologist who would be punished for refusing to train green beret medics being sent to Vietnam.[6]

Growing protests (1968)

In 1968 more collective acts of resistance would take place inside the U.S. military. Many servicemen fled the military and took sanctuary in various churches and universities. Many veterans and servicemen began involving themselves in anti-war marches, and rebellions in military stockades.[6]

At the Presidio of San Francisco a protest was staged by servicemen after another soldier was shot for walking away from a work detail.[7] During the protest a group of AWOL soldiers returned to base to join the demonstration. They were arrested and put into the stockade where they convinced other imprisoned troops to stage another protest.[8]

Later dissent (1969-1972)

Demonstrations inside and outside the army were being conducted by servicemen. More dissident soldiers began to oppose racism felt in the United States, its military, and draft policy.[6] By June, 1971, Colonel Robert Heinl declared that the army in Vietnam was "dispirited where not near mutinous." in an article in Armed Forces Journal.[4]

Activist organizations

Civilian assistance organizations

Deserters' and Veterans' organizations

Gallery

The Fort Hood Three refuse orders to go to Vietnam in 1966.

The Fort Hood Three refuse orders to go to Vietnam in 1966. Protester with a Purple Heart.

Protester with a Purple Heart. Fort Lewis Six who refused orders to go to Vietnam in 1970.

Fort Lewis Six who refused orders to go to Vietnam in 1970. Veterans protesting the Vietnam War.

Veterans protesting the Vietnam War. GIs and Veterans in peace march.

GIs and Veterans in peace march. Flyer for GIs and Veterans protest.

Flyer for GIs and Veterans protest. The Presidio 27 sit-down protest in 1968.

The Presidio 27 sit-down protest in 1968.

See also

- A Matter of Conscience

- Brian Willson

- Concerned Officers Movement

- Court-martial of Howard Levy

- Donald W. Duncan, Master Sergeant U.S. Army Special Forces early register to the Vietnam War

- Fort Hood Three

- FTA Show

- GI's Against Fascism

- GI Coffeehouses

- Movement for a Democratic Military

- Presidio mutiny

- Resistance Inside the Army

- Opposition to United States involvement in the Vietnam War

- Sir! No Sir!, a documentary about the anti-war movement within the ranks of the United States Armed Forces

- Veterans For Peace

- Vietnam Veterans Against the War

- Waging Peace in Vietnam

- Winter Soldier Investigation

- Dissent by military officers and enlisted personnel

References

- Kindig, Jessie. "GI Movement, 1968-1973: Special Section". washington.edu.

- Seidman, Derek. "Vietnam and the Soldiers' Revolt The Politics of a Forgotten History". monthlyreview.ord.

- Parsons, David (2018-01-09). "How Coffeehouses Fueled the Vietnam Peace Movement". New York Times.

- ""Fragging" and "Combat Refusals" in Vietnam". home.mweb.co.za/re/redcap/vietnam.

- Vietnam War Resisters in Canada Open Arms to U.S. Military Deserters Archived 2009-08-15 at the Wayback Machine. Pacific News Service. June 28, 2005.

- DeBenedetti, Charles (1990). GI Resistance: Soldiers and Veterans Against the War. Vietnam Generation.

- "Mutiny in the Presidio". Time. February 21, 1969. Retrieved 2008-11-25.

- Rowland, Randy. "The Presidio Mutiny". National Lawyers Guild Military Law Task Force. Archived from the original on 2008-11-19. Retrieved 2008-11-25.