Gabrielle de Coignard

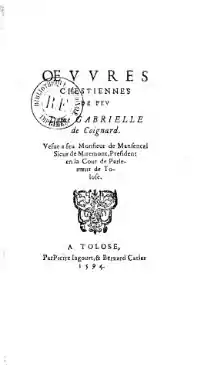

Gabrielle de Coignard (1550?–1586) was a Toulousaine devotional poet in 16th-century France. She is most well known for her posthumously published book of religious poetry, Oeuvres chrétiennes ("Christian Works"), and her marriage into the prominent political family of Toulousain president Jean de Mansencal in 1570.

Life

Though her exact date of birth is unknown, her death at the age of 36 in November 1586 provides 1550 as the likely year of her birth.[1] Her father, Jean de Coignard, was a prominent member of the elite literary society of Toulouse during the mid-16th century, acting as maître for the prestigious Académie des Jeux Floraux. [2] Records of his life indicate that Coignard received a good education fitting of her status—a luxury not afforded to women of lower classes[3]—and she was well-versed in the Catholic faith.[4] Although her father's position as maître ès Jeux Floraux and counselor at the Parlement of Toulouse[5] offered the Coignard family a comfortable lifestyle, Gabrielle de Coignard's marriage to Pierre de Mansencal in 1570 considerably elevated her social status.[6] Mansencal's father was a prominent political figure in 16th-century France, acting as the first president of the Parlement of Toulouse from 1535-1555,[7] a position which Pierre de Mansencal would assume in 1572.[8][9] Coignard and Mansencal had two daughters, Jeanne and Catherine,[10] and Coignard was left a widow and single mother after just three years of marriage when her husband died of unknown causes in 1573.[11]

There is very little information regarding the nature of Coignard's relationship with her husband, but her poems indicate that her marriage was loving and rewarding. This was a rare coincidence in a time when aristocratic marriages were generally motivated by economics and politics, but Coignard was said to have been deeply affected by Mansencal's sudden death, and current scholarship indicates that she turned to writing to cope with her grief.[12] Unlike most women in the early modern period, Coignard never remarried after the loss of her husband;[13] instead, she became more deeply immersed in her Catholic faith and vowed that God would be her only spouse.[14] Although both widowhood and religion were two major avenues through which women gained power in this time period, there is little evidence to indicate that Coignard led anything other than a rather solitary lifestyle, and after her husband's death she essentially fell into obscurity.[15] We do know, however, that she passed on her religious devotion to her two daughters, and she leveraged her elite status to provide them with the educational resources that were often withheld from women in that era.[16] It appears that the gender expectations of early modern France greatly dictated Coignard's life, and her strict adherence to the feminine virtues of silence, piety, and humility encouraged her to refuse to publish her works during her lifetime, going so far as to hide her poetry from her daughters to ensure that this wish was fulfilled.[17] In 1594, eight years after Coignard's death, Jeanne and Catherine de Mansencal published their mother's entire catalog of religious poetry under the title Oeuvres chrétiennes, which would gain substantial recognition in the early 17th century as a poetical devotional text.

Oeuvres Chrétiennes

Les oeuvres chrétiennes is a compilation of 129 individual sonnets (Les sonnets spirituels, or "Spiritual Sonnets") and 21 other poems (Les vers chrétiens, or "Christian Verses") that employ a variety of Christian themes and biblical imageries.[18] Although Oeuvres focuses on some secular themes, it is first and foremost a religious text, and its preface makes that abundantly clear. This introduction, written by Coignard's daughters, dedicates her work to two “devout” and “venerable” ladies that their mother greatly admired.[19] These two women are generally assumed to be Marguerite de Valois and Clémence Isaure, two renowned devotional poets in their own right, who greatly influenced Coignard's faith and literary career.[20] The preface also asks that the readers ignore the “fairly remarkable errors in this book that you will be likely to criticize and condemn,” instead encouraging them to recognize its “honest and virtuous” author, indicating that the Mansencals were invested in protecting their mother's legacy.[21] And indeed, Coignard's work has received some literary criticism for its lack of skill,[22] but her work has gained praise for its emotional veracity and piety.[23]

Religious themes are a constant throughout this work, with the Cross, grace, prayer, and death all figuring heavily into Coignard's poetry.[24] However, she has also received praise for her inclusion of the more worldly themes of widowhood, the body, and illness, for offering a unique perspective on womanhood in early modern France.[25] Coignard has also gained recognition for the transgressive nature of some of her works, notably her 1548-line long epic Imitation de la victoire de Judich ("Imitation of the Victory of Judith") from Les vers chrétiens. In this piece, she purposefully downplayed the more subversive acts of the biblical heroine Judith, instead highlighting her acceptable womanly values of chastity, piety, and virtue in order to cast a more favorable light on this heroine, who was often maligned by Coignard's contemporaries.[26][27] Modern scholarship on Coignard suggests that, although she was forced to work within the patriarchal confines of her society—and thus frame her poetry in a manner which upheld the dominant prescriptions for femininity of that time—Coignard nonetheless found ways to subvert sexist biblical narratives by reframing the stories of biblical heroines to focus on their virtues and accomplishments, rather than those of the male heroes within their tales.[28]

Style

Although the act of writing itself was rather subversive for women in 16th-century France, religion was perhaps the most socially accepted creative outlet available to women during this time, allowing Coignard to take advantage of this culturally sanctioned means of self-expression.[29] It was not uncommon for literate women to write or translate devotional texts in this period, though their works were rigidly structured by the dominant cultural expectations for women to be pious, chaste, silent, and humble.[30] Due to her upbringing in an educated, literary household, Coignard was well acquainted with the popular literary authors and modes of the early modern period, and her work shows the influence of writers such as Luis de Granada, Guillaume du Bartas, and Pierre de Ronsard.[31] There is some modern debate as to the extent of the popular Petrarchist influence on Coignard's work, for she was well entrenched in the literary mores of the time[32] and often employed the romantic descriptors characteristic of that style, but her poetry resoundingly rejected the sinful Petrarchan focus on bodily pleasure, instead focusing on the eternal divine pleasures of the soul.[33]

Gabrielle de Coignard, along with other women authors like Anne de Marquets and Marguerite de Navarre, was at the forefront of a religious literary movement that scholar Gary Ferguson has termed “the feminization of devotion,” which had profound impacts on creative spiritual texts throughout the early 17th century.[34] This writing style, which would later be celebrated and popularized by male authors like St. Francis de Sales, was characterized by sweetness, softness, and emotional phrasing, all of which are quite present throughout Coignard's works.[35] Her style is also unique for her constant reassertion of the female subject: her use of “je” (“I”) throughout her sonnets and vers positions herself (and women in general) as the actor within her works, offering the wife, the widow, the mother as the central character and agent in her poetry.[36] This female-subjecthood is especially notable in light of the overwhelming male-domination of the early modern French literary culture in which Coignard lived and wrote, and modern scholars have argued that it represents a subversion of idealized womanhood,[37] as well as a social shift toward this feminization of devotion.[38]

Modern Interest

Although Coignard essentially fell into obscurity after the mid-17th century, interest in her work and scholarship on her life has greatly increased since the publishing of Colette Winn's detailed annotated version of Oeuvres chrétiennes in 1995. Feminist analysis, in particular, has become a consistent feature of most research on Coignard, and this renewed interest in her life has been attributed, at least in part, to modern attempts to include women authors in literary canon.[39] Her role as a pioneer of the more feminized devotional movement in early modern French literature has been well document by Ferguson and other scholars, and the gender discourse present in her works has recently piqued the interest of feminist researchers and historical poets.[40][41][42] Her work is now being recognized as an important text in French women's history and it is gaining recognition as a rare semi-autobiographical look into the daily life of a French wife, widow, and mother in the early modern period.

Notes

- Coignard and Gregg, 4.

- Larsen and Winn, 171.

- Bankier and Lashgari, 163.

- Coignard and Gregg, 4.

- Coignard and Gregg, 4.

- Larsen and Winn, 171.

- Coignard and Gregg, 4.

- Coignard and Gregg, 4.

- Shapiro, 231.

- Larsen and Winn, 171.

- Coignard and Gregg, 5.

- Larsen and Winn, 171.

- Coignard and Gregg, 8.

- Ferguson, 198.

- Coignard and Gregg, 5

- Coignard and Gregg, 5.

- Sommers, 273.

- Coignard and Gregg, 5.

- Coignard and Gregg, 35.

- Coignard and Gregg, 6.

- Coignard and Gregg, 37.

- Coignard and Gregg, 13.

- Coignard and Gregg, 13.

- Coignard and Gregg, 7-8.

- Coignard and Gregg, 3, 8, 11.

- Larsen and Winn, 172.

- Sommers, 211 and 215.

- Sommers, 217.

- Llewellyn, 77.

- Llewellyn, 77.

- Larsen and Winn, 171 and 172.

- Larsen and Winn, 172.

- Llewellyn, 81.

- Ferguson, 187.

- Ferguson, 189.

- Ferguson, 195.

- Llewellyn, 82.

- Ferguson, 195.

- Bankier and Lashgari, 6.

- Larsen and Winn, xxi and 174.

- Ferguson, 187.

- Llewellyn, 82.

References

- Bankier, Joanna, Deirdre Lashgari, and Doris Earnshaw. Women Poets of the World. New York: Macmillan, 1983.

- Coignard, Gabrielle de, and Melanie E. Gregg. Spiritual Sonnets: A Bilingual Edition. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2004.

- Ferguson, Gary. "The Feminisation Of Devotion: Gabrielle De Coignard, Anne De Marquets, And François De Sales." Women's Writing in the French Renaissance. 187-206. Cambridge, England: Cambridge French Colloquia, 1999.

- Larsen, Anne R., and Colette H. Winn. Writings by Pre-revolutionary French Women: From Marie De France to Elisabeth Vigée-Lebrun. New York: Garland Publishing, 2000.

- Llewellyn, Kathleen M. "Passion, Prayer, And Plume: Poetic Inspiration In The Oeuvres Chrétiennes Of Gabrielle De Coignard." Dalhousie French Studies 88. (2009): 77-86.

- Shapiro, Norman R. French Women Poets of Nine Centuries: The Distaff and the Pen. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2008.

- Sommers, Paula. "Gendered Readings Of The Book Of Judith: Guillaume Du Bartas And Gabrielle De Coignard." Romance Quarterly 48.4 (2001): 211.

External links

- Spiritual Sonnets on Google Books