Galeas per montes

Galeas per montes is the name by which an enterprise of military engineering made between December 1438 and April 1439 by the Republic of Venice and consisting of the transport of ships, Galleys and frigates from the Adriatic Sea to Lake Garda, climbing the river Adige to Rovereto and transporting ships by land to Torbole, on the northern shores of the lake. A journey of about 20 km through the mountains and the Loppio Lake, now almost disappeared following the construction of the Galleria Adige-Garda, which emptied the lake above.

Context

The Republic of Venice was at the time a power in the Mediterranean and in the fifteenth century began a phase of expansion into the Veneto and Lombardy mainland through military conquests (e.g. Padua) or spontaneous "dedication" as Vicenza. Brescia, to escape the Duchy of Milan, became loyal to Republic of Venice on November 20, 1426 [1]

In the 1438, the Duke of Milan Filippo Maria Visconti, went to war against the Republic of Venice and with a series of lucky shots took control of Lombard lands up to the southern shores of lake of Garda. Brescia was under siege by "captain of fortune" Niccolò Piccinino, in the pay of the Duke of Milan, but resisted, calling on the Venetian Senate for assistance.

The Piccinino captain took control of the entire southern sector of the lake so the Venetian warlord Gattamelata (Erasmo da Narni) could only access from the north of lake of Garda that is from Torbole or from Riva, now Riva del Garda. The milanese army was also barricaded in the castles of Peschiera del Garda and Desenzano, making a head-on collision too expensive. The Serenessima then decided to prepare a military plan that would allow its troops to surprise the Visconti army by moving north of the lake.

On 1 December 1438, after a very long session, the Minor Consiglio approved the proposal formulated by Blasio de Arboribus, at the service of the Serenissima, and by a Greek sailor, Nicolò Sorbolo.

Project and realization

The two planned to drag along the Adige valley a fleet of ships, to take them dry before Rovereto and then drag them on wooden rollers along the route of Loppio valley to then drop them in Lake Garda near Torbole. From there, the Venetian fleet would have attacked by surprise the Milanese, anchored to Desenzano, cutting the road to the Visconti militia of guarding Peschiera del Garda and forcing the blockade in order to have successively free for Brescia and then also for Milan.

Realization

The fleet, consisting of 25 large boats, 2 galleys and 6 frigates (or 6 galleys and 2 frigates according to other sources), sailed in January 1439 from Venice entering the mouths of the Adige near Sottomarina di Chioggia, went up the river passing through Legnago and Verona. There, being the Adige in lean, they had to apply to the boats a sort of "floating" of wood to reduce the draft and continue through the sluiced of Ceraino up to over Lavini di Marco near Lagarina Valley south of Rovereto, and to Mori. Hundreds of workers were hired: diggers and carpenters who created a new road made of wooden planks, leveling the ground and removing from the track plants, boulders and even two houses. In the town of Mori, just south of Rovereto, the fleet was rolled up and loaded onto new invented machines. Then, with the help of 2000 oxen commandeered in the vicinity and hundreds of sailors and rowers of ships with local men, the boats were rolled on rollers over the wooden planks road passing through the villages of Mori, and the Lake of Loppio, which allowed to put the boats in water for 2 km. Then the fleet was pulled again and dragged along the steep slope to the Pass of San Giovanni. During the steep descent from the Pass towards Nago the ships were held with large ropes secured to winches and slid slowly towards the shore of the lake, to Torbole. The writer of the time that the weight of the ships was such that several old olive trees, which had been set the winches, were literally torn from the ground and that, to stop the descent, resorted to the advent of waiting for the strong wind that blowing from the south in the afternoon and explaining the sails to lighten the weight of the ships. The complex operation, which lasted three months, cost to the Republic of Venice the fabulous figure of 15,000 Ducats, but it was one of the most important military engineering works ever built as such, it became famous throughout Europe.

Gallery

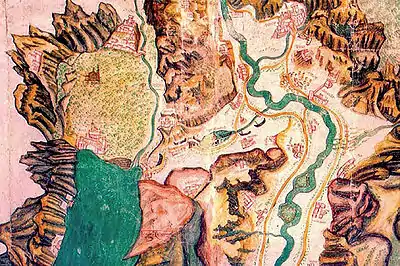

Along the route from the Adige river to the Loppio lake

Along the route from the Adige river to the Loppio lake The ascent of ships

The ascent of ships The passage through the Adige to Ceraino

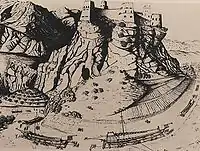

The passage through the Adige to Ceraino The dangerous descent from the San Giovanni Pass to Torbole

The dangerous descent from the San Giovanni Pass to Torbole

Consequences

The transport of the fleet, however, was not able to remain hidden to the Milanese and so the surprise factor on which Piero Zen, captain of the Venetian fleet, was depending, was lost. The clash occurred near Desenzano and the victory was of the Milanese, who were stronger in number and who captured part of the fleet. Only two Venetian galleys were able to repair in the port of Torbole. Brescia was not freed from the siege, but thanks to the naval control of the northern part of Lake Garda, the Venetians managed to bring aid and food, allowing the city to resist another year's siege.

During the year 1439 was set up in Torbole a second and more powerful Venetian fleet with the material transported from Venice through the already tested route Adige-Loppio-Torbole. In the clash of April 1440 the new fleet, commanded by Stefano Contarini clashed with the Milanese off the Ponale and this time won the battle, acquiring complete control of the lake.

In the ceiling of the Maggior Consiglio room in Palazzo Ducale of Venice a painting by Tintoretto represents the very hard battle with the Milanese.

Notes

- Alemano Barchi, "Annotazioni alla Cronologia Bresciana civile" 1832 - "... For the noble pacts that the Brescia dedication, she preserved his Senate with the name of the General Council until 1797 ...".

Citation: ”Unica viache ancor rimanesse ad approvvigionare Brescia era quella del lago di Garda, poiché essendo la costa orientale di esso formata dal Veronese, imbarcati colà i viveri, facilmente si potevano condurre a Brescia, e se il Piccinino fosse accorso a vietarlo avrebbe facilmente lasciata libera o poco munita la strada da Brescia a Verona. Ma nel lago non avevano i Veneziani alcun naviglio, mentre il nemico teneva un'armetta a Peschiera, e altri posti fortificati all'intorno.

In tanta difficoltà la Repubblica aveva accolto fino dal dicembre 1438 il temerario progetto di un Blasio de Arboribus (o Nicolò Carcavilla o Caravilla) e Nicolò Sorbolo di far passare pei monti una flottiglia dall'Adige nel lago. Componevasi di venticinque barche e sei galere, le quali dalla foce dell' Adige furono fatte salire fino quasi a Roveredo, ma di là erano ancora da dodici a quindici miglia per giungere a Torbole per terreno erto ed alpestre. In mezzo a quei monti e alle falde della catena del monte Baldo trovasi il lago di s. Andrea, nel quale appunto volevasi far entrare la flottiglia.

A quest'uopo furono radunati fino a duemila buoi, abbisognandone ben cento venti paia per ogni galera; gran numero di guastatori, operai, ingegneri sgombravano i borri, costruivano ponti, spianavano la strada, e così, dopo indicibili sforzi e fatiche, poté giungere l'armetta nel lago di s. Andrea. Restava a superare il monte Baldo, e l'umana industria e il ferreo volere anco a questo pervennero e con istrano spettacolo i navigli trovaronsi alfine sulla vetta del monte.

Di colà bisognava gettarli nel lago, operazione non meno difficile pei pericoli della discesa; in quel ripido pendìo legavansi le barche agli alberi e ai macigni, col mezzo di argani allentavansi a poco a poco le funi, e i navigli si calavano da quegli orridi precipizii. Così dopo quindici giorni di viaggio per terra, l'armetta giunse senz'alcun sinistro a Torbole, donde fu lanciata in acqua e munita.

Fu impresa maravigliosa che costò alla Repubblica ben quindici mila ducati, ma sciaguratamente presso che inutile per lo scopo di vettovagliare Brescia, poiché accorso il Piccinino col. suo navilio, poco sollievo poterono avere i Bresciani e il comandante veneziano Pietro Zeno dovette ritirarsi a Torbole e mettersi in salvo dietro a forte steccato.”

Eugenio Musatti, Storia di Venezia, 1880.

Bibliography

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Battles on Lake Garda. |

- Paolo Renier Testimonianze sul trasporto delle navi da Venezia al Garda eseguito dai veneziani nel 1439, Venezia 1967

- Paolo D. Malvinni La magnifica intrapresa. Galeas per montes conducendo, Curcu & Genovese, Trento 2010 ISBN 978-889673717-0

- Samuel Romanin Storia documentata di Venezia - Tomo 4, 1853-1861.

- David Sanderson Chambers The Imperial Age of Venice 1380-1580 - (History of European Civilization Library), Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1970

- Clemente Cavalcabo Idea della storia e delle cossuetudini antiche della valle Lagarina ed...del Roveretano, 1776

- Eugenio Musatti, Storia di Venezia, 1880, tomo I, p. 270 e seg.