Ganoderma sessile

Ganoderma sessile is a species of polypore fungus in the Ganodermataceae family. This wood decay fungus is found commonly in Eastern North America, and is associated with declining or dead hardwoods. There is taxonomic uncertainty with this fungus since its circumscription in 1902.[1]

| Ganoderma sessile | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Division: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | |

| Species: | G. sessile |

| Binomial name | |

| Ganoderma sessile Murrill (1902) | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Fomes sessilis (Murrill) Sacc. & D. Sacc. Polyporus sessilis (Murrill) Lloyd Ganoderma subperforatum Atkinson | |

Taxonomy and history

Murrill described 17 new Ganoderma species in his treatises of North American polypores, including for example, G. oregonense, G. sessile, G. tsugae, G. tuberculosum and G. zonatum. Most notably and controversial was the typification of Ganoderma sessile, which was described from various hardwoods only in the United States.[2][1] The specific epithet "sessile" comes from the sessile, or without typical stem, nature of this species when found growing in a natural setting. Ganoderma sessile was distinguished based on a sessile fruiting habit, common on hardwood substrates and occasionally having a reduced, eccentric or “wanting” stipe.[2][1] In 1908, Atkinson considered G. tsugae and G. sessile as synonyms of G. lucidum, but erected the species G. subperforatum from a single collection in Ohio on the basis of having “smooth” spores.[3] Although he did not recognize the genus Ganoderma, but rather kept taxa in the genus Polyporus, Overholts agreed with Atkinson, and considered G. sessile as a synonym of the European G. lucidum .[4]

In a 1920 report on Polyporaceae of North America, Murrill conceded that G. sessile was closely related to the European G. lucidum .[5] It is difficult to determine if this concession was the result of political scrutiny or from a scientific foundation, due to the retention of the name by Murrill in a later publication [6] and a single herbarium collection in 1926 (www.mycoportal.org).

Approximately a decade later, Haddow considered G. sessile a unique taxon, but suggested Atkinson’s G. subperforatum was a synonym of G. sessile, on the basis of the “smooth” spores, which was the original basis of G. subperforatum when earlier erected by Atkinson in 1931.[7] Until this point, all identifications of Ganoderma taxa were based on fruiting body morphology, geography, host, and spore characters.

In 1948 and then amended in 1965, Nobles characterized the cultural characteristics of numerous wood-inhabiting hymenomycetes including Ganoderma taxa.[8][9] Her work laid the foundation for culture-based identifications in this group of fungi.[9] Nobles recognized that there were differences in cultural characteristics between G. oregonense, G. sessile, and G. tsugae .[9][8] Although Nobles recognized G. lucidum in her 1948 publication as a correct name for the taxon from North American isolates that produce numerous broadly ovoid to elongate chlamydospores (12.0-21.0 x 7.5-10.5 μm), she corrected this misnomer in 1968 by amending the name to G. sessile .[9] Clarifying further, Bazallo & Wright and Steyaert agree with Haddow’s distinction between G. lucidum and G. sessile on the basis of “smooth” spores, but they synonymize G. sessile with G. resinaceum, a previously described European taxon.[10][11] Later Adaskaveg and Gilbertson demonstrated the similarity in culture morphology and that vegetative compatibility was successful between the North American taxon recognized as ‘G. lucidum’ and the European G. resinaceum [12].

In the monograph of North American Polypores written in 1986, which is still the only comprehensive treatise on this group of fungi unique for North America, the authors Gilbertson and Ryvarden do not recognize G. sessile, but rather recognize the five following laccate species being present in the U.S.: G. colossum (Fr.) C.F. Baker (current name: Tomophagus colossus (Fr.) Murrill), G. curtisii, G. lucidum, G. oregonense, and G. tsugae [13]. They considered G. sessile along with other laccate species synonyms with G. lucidum, and in the comments under G. lucidum they discuss the taxonomic chaos of this particular species complex, and leave it somewhat unresolved.

Molecular taxonomy

In a multilocus phylogeny, the authors revealed that the global diversity of the laccate Ganoderma species included three highly supported major lineages that separated G. oregonense/G. tsugae from G. zonatum and from G. curtisii/G. sessile, and these lineages were not correlated to geographical separation.[14] These results agree with several of the earlier works focusing mostly on morphology, geography and host preference showing genetic affinity of G. resinaceum and G. sessile, but with statistical support separating the European and North American taxa.[14] Also, Ganoderma curtisii and G. sessile were separated with high levels of statistical support, although there was not enough information to say they were from distinct lineages. Lastly, G. sessile was not sister to G. lucidum. The phylogeny supported G. tsugae and G. oregonense as sister taxa to the European taxon G. lucdium sensu stricto.[14]

Description

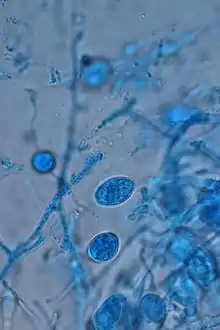

Fruiting bodies annual and sessile (without a stipe) or pseudostipitate (very small stipe). Fruiting bodies found growing on trunks or root flares of living or dead hardwood trees. Very common taxon, being found in practically every state East of the Rocky Mountains within the United States. Mature fruiting bodies are laccate and reddish-brown, often with a wrinkled margin if dry. Fruiting bodies are shelf-like if on stumps or overlapping clusters of fan-shaped (flabelliform) fruiting bodies if growing from underground roots, and range in size of 3-20 cm in diameter. Hymenium white, bruising brown, and poroid with irregular pores that can range in shape from circular to angular. The context tissue is cream colored and can be thin to thick and on average the same length as the tubes. Black resinous deposits are never found embedded in the context tissue, but concentric zones are often found. Spores appear “smooth”, or nearly so, due to the fine (thin) echinulations from the endosporium, which can differentiate them from other common Eastern North American species such as Ganoderma curtisii (Berk.) Murrill. Elliptical to obovate to obpyriform chlamydospores formed in vegetative mycelium, and are abundant in cultures.[1][9][14]

Uses

For centuries, laccate (varnished or polished) Ganoderma species have been used as traditional medicine in many parts of Asia. These species are often mislabeled as G. lucidum', although genetic testing has shown this to be multiple species such as G. lingzhi, G. multipileum, and G. sichuanense [15][16] Research has been conducted on Asian species, but limited information is available for the medicinal properties of the North American laccate Ganoderma species; although it is often used to make tea, similar to the cultivated Asian species. Ganoderma sessile is the most prevalent species in Eastern North America and is likely the species that many used medicinally in the United States.

References

- Murrill, W. A. 1902. The Polyporaceae of North America, genus I Ganoderma. Bull. Torrey Bot. Club 29:599-608.

- Murrill, W. A. 1908. Agaricales (Polyporaceae). North Amer. Flora 9:73-131.

- Atkinson, G. F. 1908. Observations on Polyporus lucidus Leys and some of its Allies from Europe and North America. Botanical Gazette 46:321-338.

- Overholts, L. O. 1915. Comparative Studies in the Polyporaceae. Annals of the Missouri Botanical Garden 2:667-730.

- Murrill, W. A. (1920). "Corrections and additions to the Polypores of temperate North America". Mycologia. 12 (1): 6–24. doi:10.2307/3753482. JSTOR 3753482.

- Murrill, W. A. (1922). "Index to Illustrations of Fungi, XXIII-XXXIII". Mycologia. 14 (6): 332–334. doi:10.2307/3753081. JSTOR 3753081.

- Haddow, W. R. (1931). "Studies in Ganoderma". Journal of the Arnold Arboretum. 12: 25–46.

- Nobles, M. K. 1948. Studies in Forest Pathology. IV. Identification of Cultures of Wood-Rotting Fungi. Can. J. Res. 26:281-431.

- Nobles, M. K. 1965. Identification of cultures of wood-inhabiting Hymenomycetes. Canadian journal of Botany 43:1097-1139.

- Bazzalo, M. E., and Wright, J. E. 1982. Survey of the Argentine Species of the Ganoderma lucidum Complex. Mycotaxon 16:293-325.

- Steyaert, R. L. 1980. Study of Some Ganoderma Species. Bull. du Jardin Bot. Nat. de Belgique/ Bull. van de Nat. Plantentuin van Blegie 50:135-186.

- Adaskaveg, J. E., and Gilbertson, R. L. 1986. Cultural studies and genetics of sexuality of Ganoderma lucidum and G. tsugae in relation to the taxonomy of the G. lucidum complex. Mycologia:694-705.

- Gilbertson, R., and Ryvarden, L. 1986. North American Polypores, vol. 1. Abortiporus to Lindteria, Fungiflora, Oslo. 443 pp., 1987. North American Polypores 2.

- Zhou, L. W.; Cao, Y.; Wu, S. H.; Vlasak, J.; Li, D. W.; Li, M. J.; Dai, Y. C. (2015). "Global diversity of the Ganoderma lucidum complex (Ganodermataceae, Polyporales) inferred from morphology and multilocus phylogeny". Phytochemistry. 114: 7–15. doi:10.1016/j.phytochem.2014.09.023. PMID 25453909.

- Hennicke, F., Z. Cheikh-Ali, T. Liebisch, J.G. Maciá-Vicente, H.B. Bode, and M. Piepenbring. 2016. Distinguishing commercially grown Ganoderma lucidum from Ganoderma lingzhi from Europe and East Asia on the basis of morphology, molecular phylogeny, and triterpenic acid profiles. Phytochemistry 127:29–37.

- Hapuarachchi, K., T. Wen, C. Deng, J. Kang, and K. Hyde. 2015. “Mycosphere Essays 1: Taxonomic Confusion in the Ganoderma lucidum Species Complex.” Mycosphere 6:542–559.

External links

- "Ganoderma sessile Murrill 1902". MycoBank. International Mycological Association. Retrieved 2015-04-05.

- Ganoderma sessile images at Mushroom Observer

- Ganoderma sessile in Index Fungorum