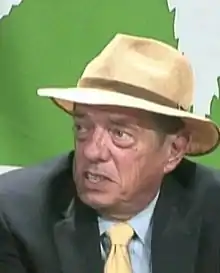

Gatewood Galbraith

Louis Gatewood Galbraith (January 23, 1947 – January 4, 2012) was an American author and attorney from the U.S. Commonwealth of Kentucky. He was a five-time political candidate for governor of Kentucky.

Gatewood Galbraith | |

|---|---|

| |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Louis Gatewood Galbraith January 23, 1947 Carlisle, Kentucky, U.S. |

| Died | January 4, 2012 (aged 64) Lexington, Kentucky, U.S. |

| Political party | Democratic (before 1999; 2007–2011) Reform (1999–2000) Independent (2000–2003, 2011–2012) |

| Education | University of Kentucky |

Early life, education, and law career

Born in Carlisle, Kentucky to Henry Clay and Dollie Galbraith, on January 23, 1947, Gatewood was the fourth of seven children. He graduated from the University of Kentucky in 1974 and from the University of Kentucky College of Law in 1977.[1] Galbraith's law practice focused on criminal law and personal injury civil actions.[2] According to his Linkedin resume,[3] he specialized in the difficult cases, and his interest included the preservation of the Constitution and justice for all.[4] Beginning around June 1997, he spent nearly six years driving back and forth from Lexington, Kentucky where he resided to Bowling Green, Kentucky, practicing as a pro bono attorney in the first felony medical marijuana defense case of advocate, minister and patient Mary L. Thomas, a/k/a Rev. Mary Thomas-Spears (Indictment #97-CR-517). Charged originally with six felonies for trafficking in a controlled substance, marijuana. This case made U.S. legal history in a marijuana trafficking cases before the Kentucky Courts and the Honorable Judge John D. Minton, Jr. (then known as "hang 'em high Minton") in 2001/2002, when Judge Minton granted a stay in the case after the appeal in the case had been denied by the Kentucky Court of Appeals in 2001.[5] Shortly after this, a review of tax law changes enacted the Marijuana Tax Stamp by the 2003 General Assembly. John D. Minton, Jr. was later elected to the Commonwealth Court of Appeals and then moved up to the Supreme Court and on March 3, 2011 Governor Steve Beshear's Communications Office released a press statement headed "Beshear signs landmark corrections reform bill into law" which decriminalizes personal use of up eight ounces of marijuana, reducing it to a ticketable offense.[6]

During this time, Gatewood Galbraith also represented Richard J. Rawlings, former president for many years and an official board member of the U.S. Marijuana Party, pro bono in 2011 in Barren County, Kentucky at the Barren County Courthouse. Rawlings faced felony marijuana cultivation, possession, and paraphernalia charges stemming from a raid on his girlfriend's (Sheree Krider) property in Cave City. Crider was a former vice president of the U.S. Marijuana Party and a board member herself. The case, on Nov. 21st, 2011, ended with a [7] plea bargain where felony charges were dropped and Richard Rawlings agreed to time served, court costs and four weekends to serve (one weekend for each plant that didn't have a tax stamp).

Galbraith died from natural causes, including complications from emphysema,[8] on January 4, 2012 at his home in Lexington, Kentucky.[9][10]

Political activism

Gatewood was active in many issues and groups. In 1995, Gatewood was charged with interfering with a procession after protesting the presence of a UN-themed float at an Independence Day parade. In 2004, he became a columnist for the Louisville-based alternative weekly Snitch Newsweekly, writing on cases he had handled, and debating with other contributors on civil liberties.

In his writings and speeches Galbraith went into detail on what he termed "Synthetic Subversion". His theory sought to explain when, how and why America, specifically Kentucky, moved from an agricultural agrarian society into an industrial synthetic society. Galbraith claimed that the beginning of this shift can be traced back to the New Deal era spearheaded by Franklin D. Roosevelt's administration. Galbraith argued that until the early 1930s, America and Kentucky relied solely on agriculture to fuel the economy, but that out of necessity, Roosevelt shifted America toward a more industrial (synthetic) society fueled by alliances with "Greedy Corporations."

He worked closely with his longtime friend and supporter Norm Davis, gun rights advocate, activist and founder of the grassroots organization "Take Back Kentucky" in support of "smaller government and preservation of our constitutional freedoms and rights with-in the commonwealth."[11]

Galbraith supported the legalization of recreational marijuana use, arguing that the framers of the US Constitution "did not say we have a Constitutional right to possess alcohol. They said we have a Constitutional right to privacy in our homes, under which fits the possession of an extremely poisonous alcohol. Now this is the law in Kentucky today. In fact, it is these rulings that keep the Kentucky State Police from kicking down the doors of people possessing alcohol in Kentucky's 77 'dry' counties right now and hauling their butts off to jail. Now Marijuana is a demonstrably less harmful substance than alcohol and presents far less of threat to public welfare. So it also fits in a person's right to privacy in their home. It's beyond the police power of the state as long as I don't sell it and it's for my own personal use."[12]

During a debate with former Kentucky Attorney General Greg Stumbo he said, "He obviously thought he could hang me over the marijuana issue, and here I was explaining Constitutional Law to him which, I still don't think he comprehends."

Galbraith appeared onstage, on TV and in films with many notable public figures, including well known environmental activist Julia Butterfly Hill, author/filmmaker Christopher Largen, author/activist Jack Herer, country music artist/singer/film star Willie Nelson, and artist/author/film star/producer Woody Harrelson.

Galbraith appeared in the 2003 movie Hempsters: Plant the Seed, along with Woody Harrelson, Ralph Nader and Julia "Butterfly" Hill.[13]

He was featured in the documentary film A NORML Life.[14]

Political campaigns

Galbraith ran for various offices in Kentucky, including Agriculture Commissioner, Attorney General, and for a seat in the United States House of Representatives. Galbraith also ran for Governor five times – as a Democrat in 1991, 1995, and 2007, as a Reform Party candidate in 1999,[15] and lastly as an independent in 2011.[2]

Galbraith was a vocal advocate for ending the prohibition of cannabis[16] and was known for his quips.[17]

Included in Galbraith's platform[18] were campaign promises of implementing a freeze on college tuition, a $5,000 grant or voucher provided to motivated high school graduates to any college or vocational school, incorporating more technology into the education process, restoring hemp as an agricultural crop, ending cannabis prohibition in Kentucky, restoring of voting and gun rights of non-violent felons, agricultural market development, stricter environmental protections, recreational and tourism development, water standard enforcement, expansion of fish and wildlife programs, abolition of state worker furloughs, expansion of energy development, Internet access to all counties, abolition of the income tax for those who earn fifty thousand dollars or less, small business tax exemptions, job development, a return investment policy, the establishment of regional economic development offices, marketing Kentucky's signature industries, the prohibition of fracking and mountaintop removal mining. He raised $100,000 of his $500,000 budget and was endorsed by the United Mine Workers of America, the first time the union had backed an independent.[19]

1983 run for Agriculture Commissioner

Galbraith ran for Kentucky Agriculture Commissioner after incumbent Democrat Alben Barkley II decided to run instead for lieutenant governor. Galbraith ran as a Democrat and ranked last among four candidates in the Democratic primary with 12 percent of the vote. David Boswell won with a plurality of 35 percent.[20]

1991 gubernatorial election

In 1991 Galbraith ran for Governor of Kentucky. He ranked last in a four candidate Democratic primary with five percent of the vote. Lieutenant Governor Brereton Jones won the primary with a plurality of 38 percent.[21]

1995 gubernatorial election

Galbraith ran for governor again at the end of Brereton Jones's term. In the Democratic primary, he ranked fourth in a five candidate field with nine percent of the vote. Lieutenant Governor Paul Patton won with a plurality of 45 percent of the vote.[22] In the general election, Galbraith decided to run as a write-in candidate and got just 0.4 percent of the vote.[23]

1999 gubernatorial election

Galbraith ran again for governor in 1999. This time he ran on the Reform Party ticket and got 15 percent of the vote, the best statewide general election performance of his career. The Republican candidates were Peppy Martin for governor and Wanda Cornelius for lieutenant governor. Incumbent Democratic Governor Paul Patton won re-election with 61 percent of the vote.[24]

2000 congressional election

Galbraith ran for Congress in Kentucky's 6th congressional district in 2000 as an independent. Incumbent Republican U.S. Congressman Ernie Fletcher won re-election with 53 percent of the vote. Democratic nominee and former U.S. Congressman Scotty Baesler got 35 percent of the vote. Galbraith ranked third with 12 percent.[25]

2002 congressional election

In 2002, Galbraith decided to run in the 6th District again. Incumbent Republican U.S. Congressman Ernie Fletcher won re-election with 72 percent of the vote. No Democrat filed to run against him. Galbraith, as an independent, ranked second with 26 percent of the vote, his highest percentage in an election.[26]

2003 run for Kentucky Attorney General

Galbraith decided to run for Kentucky Attorney General as an independent. Democratic State Representative Greg Stumbo won the election with 48 percent of the vote. Republican nominee Jack Wood ranked second with 42 percent of the vote. Galbraith ranked third with 11 percent.[27]

2007 gubernatorial election

Galbraith decided to run for governor a fourth time. This time, he decided to run as a Democrat, the first time since 1995. In the Democratic primary, Galbraith ranked fifth in a six-candidate field with six percent of the vote. However, he carried Nicholas County with a 32 percent plurality. Lieutenant Governor Steve Beshear won with a plurality of 41 percent of the vote. Bruce Lunsford ranked second with 21 percent. Former Lieutenant Governor Steve Henry ranked third with 17 percent. Speaker of the Kentucky House Jody Richards ranked fourth with 13 percent.[28]

2011 gubernatorial election

In 2011, Galbraith decided to run for governor a fifth time. This time, he decided to run as an independent.[29] Incumbent Democratic Governor Steve Beshear won re-election with 56 percent of the vote. Republican State Senator David Williams of Burkesville, the President of the State Senate, ranked second with 35 percent. Galbraith trailed with nine percent.[30]

Published work

- Galbraith, Gatewood (2004). The Last Free Man In America Meets The Synthetic Subversion. Outskirts Press. ISBN 1-932672-35-4.

References

- "Kentucky Political Figure Gatewood Galbraith Dead at 64". www.wuky.org. Retrieved 2020-04-21.

- Gatewood Galbraith Dies At 64, WLEX-TV, 2012-01-04, archived from the original on 2012-01-08, retrieved 2012-01-04

- Gatewood Galbraith Linkedin profile

- Commonwealth vs Mary L. Thomas Indictment # 97-CR-517 Warren Circuit Court Division No 2

- Kentucky Revenue Cabinet Annual Report 2002–2003 Archived 2013-06-06 at the Wayback Machine

- Governor Steve Beshear's Communications Office Gov. released "Beshear signs landmark corrections reform bill into law" Archived 2011-12-02 at the Wayback Machine Press Release Date: Thursday, March 3, 2011 "I'm pleased we're making progress in tackling the problems facing our penal code," Chief Justice of Kentucky John D. Minton Jr. said. "With all three branches involved in this deliberative process, I'm confident that the outcome will be positive for Kentucky."

- Video

- WKYT. "New information on Gatewood Galbraith's final days". www.wkyt.com. Retrieved 2020-06-02.

- Coroner: Galbraith Died Of Natural Causes, WLEX-TV, 2012-01-04, archived from the original on 2012-01-09, retrieved 2012-01-04

- Political figure Gatewood Galbraith dies, WKYT-TV, 2012-01-04, archived from the original on 2012-01-09, retrieved 2012-01-04

- Take Back Kentucky

- THE LAST FREE MAN IN AMERICA

- The Hempsters Plant the Seed

- A NORML Life

- Loftus, Tom (January 23, 2007). "Galbraith announces for governor". The Courier-Journal. Retrieved 2007-01-31.(registration required)

- Bullard, Gabe (2012-01-05), Colorful Kentucky Politician Gatewood Galbraith Dies, NPR, retrieved 2012-01-05

- "Read some of Gatewood's best quips, quotes and barbs through the years", Lexington Herald-Leader, 2012-01-04, retrieved 2012-01-04

- Gatewood Galbraith speaks at Fancy Farm 2011, courier-journal.com

- Southern Political Report, December 15, 2010, "Governor's Race to be Hotly Contested" Archived 2012-09-17 at Archive.today

- "KY Agriculture Commissioner – D Primary Race – May 23, 1983". Our Campaigns. Retrieved 2012-08-11.

- "KY Governor – D Primary Race – May 28, 1991". Our Campaigns. Retrieved 2012-08-11.

- "KY Governor – D Primary Race – May 23, 1995". Our Campaigns. Retrieved 2012-08-11.

- "KY Governor Race – Nov 07, 1995". Our Campaigns. Retrieved 2012-08-11.

- "KY Governor Race – Nov 02, 1999". Our Campaigns. Retrieved 2012-08-11.

- "KY District 6 Race – Nov 07, 2000". Our Campaigns. Retrieved 2012-08-11.

- "KY District 6 Race – Nov 05, 2002". Our Campaigns. Retrieved 2012-08-11.

- "KY Attorney General Race – Nov 04, 2003". Our Campaigns. Retrieved 2012-08-11.

- "KY Governor – D Primary Race – May 22, 2007". Our Campaigns. Retrieved 2012-08-11.

- Cook, Rhodes (2013-11-05). America Votes 30: 2011-2012, Election Returns by State. CQ Press. ISBN 978-1-4522-9017-1.

- "KY Governor Race – Nov 08, 2011". Our Campaigns. Retrieved 2012-08-11.

External links

- Official website

- Appearances on C-SPAN

- Louis Gatewood Galbraith at Find a Grave

- Guide to the Gatewood Galbraith papers, 1935–2013, undated housed at the University of Kentucky Libraries Special Collections Research Center