Gnaeus Calpurnius Piso (consul 23 BC)

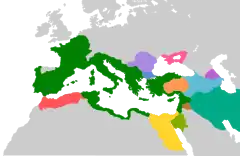

Gnaeus Calpurnius Piso[note 1] (fl. 1st century BC) was a high ranking Roman aristocrat and senator. He was firmly traditionalist and opposed the populist First Triumvirate, and later Julius Caesar. He fought against Caesar in the Great Roman Civil War and against his adopted son, Octavian, in the War of the Second Triumvirate; both times on the losing side.

Gnaeus Calpurnius Piso | |

|---|---|

.svg.png.webp) | |

| Consul of the Roman Republic | |

| In office January – December 23 BC | |

| Preceded by | Caesar Augustus with Gaius Norbanus Flaccus |

| Succeeded by | Marcus Claudius Marcellus Aeserninus with Lucius Arruntius |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Battles/wars | Great Roman Civil War • Battle of Ilerda • Battle of Ruspina • Battle of Thapsus War of the Second Triumvirate • Battle of Philippi |

He was twice pardoned, and subsequently retired from politics. He was unexpectedly appointed consul in 23 BC by the Emperor Augustus, whom he served alongside. In mid-term Augustus fell ill and was expected to die, which would, in theory, have left Piso as the highest authority in the state. In the event, Augustus recovered.

Background

Calpurnius Piso bore the same name as his father, Gnaeus Calpurnius Piso. He belonged to the gens Calpurnia, one of the most distinguished Roman gentes, which was of consular rank since 180 BC. The Calpurnii Pisones formed the main branch of the gens, and already counted 8 consuls by 23 BC. Piso married a daughter of a Marcus Popillius and they had at least two sons: Gnaeus Calpurnius Piso, who later became consul in 7 BC; and Lucius Calpurnius Piso, consul in 1 BC.[3]

Early career

Piso's father was one of the participants in the Catiline Conspiracy, a plot by a group of aristocrats and disaffected veterans led by the distinguished ex-general and military governor Lucius Sergius Catilina and aimed at overthrowing the Roman Republic with the help of foreign armed forces.[4][5] Despite this his son was a strong supporter of the self described optimates, or boni ("good men"). The boni were the traditionalist senatorial majority of the Republic, politicians who believed that the role of the Senate was being usurped by the legislative people's assemblies for the benefit of a few demagogic social reformers (known as the populares). The optimates were against anyone who attempted to use these legislative assemblies to reform the state.[6] As such, Piso was an opponent of the First Triumvirate, an informal political alliance of Julius Caesar, Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus (Pompey the Great), and Marcus Licinius Crassus.[7]

Piso first came to notice in late 66 BC when he prosecuted Gaius Manilius (also known as Gaius Manilius Crispus), a plebeian tribune who was a supporter of Pompey. The prosecution was political; Manilius had passed laws which the optimates disapproved of. Specifically the lex Manilia which gave Pompey command of the Roman armies in the east during the war against Mithridates. Manilius was initially defended by Cicero, but he dropped the case after the trial was violently disrupted by a paid mob. Piso pressed ahead with the trial, and Manilius fled the city ahead of a guilty verdict.[8] "Carried away by his youthful enthusiasm",[9] Piso leveled serious allegations at Manilius' powerful sponsor, Pompey, whom he disliked. Amused, Pompey asked Piso why he did not go further and prosecute him as well. Piso bitingly replied:

Give me a guarantee that you will not wage a civil war against the Republic if you are prosecuted, and I shall at once send the jurymen to convict you and send you into exile rather than Manilius.[9]

Feeling threatened by populist politician and general Julius Caesar, the optimates enlisted Pompey into their ranks in 53. In 50 the Senate, led by Pompey, ordered Caesar to disband his army and return to Rome because his term as a governor had ended.[10] Caesar thought he would be prosecuted if he entered Rome without the immunity enjoyed by a magistrate. On 10 January 49 he crossed the Rubicon river, the boundary of Italy, and ignited the Great Roman Civil War. He marched rapidly on Rome and captured it. Pompey, the optimates, and most of the Senate fled to Greece. Piso was sent to Hispania Ulterior (in modern Spain). There he served as a proquaestor, a type of military auditor, under Pompey's legates (legionary commanders) Lucius Afranius and Marcus Petreius.[4][1] Taking advantage of Pompey's absence from the Italian mainland, Caesar made an astonishingly fast 27-day, west-bound forced march to Hispania and destroyed the Pompeian army in the Battle of Ilerda.[1][4]

After the defeat of the Pompeian forces in Hispania, Piso escaped to North Africa. There the optimates raised an army which included 40,000 men (about eight legions), a powerful cavalry force led by Caesar's former right-hand man, the talented Titus Labienus, forces from local allied kings, and sixty war elephants. This force was commanded by Metellus Scipio, who placed Piso in command of the Numidian cavalry.[2]

Caesar made an ill-planned and disorganised landing in Africa on 28 December 47. He had insufficient food and fodder, which forced him to break up his forces to forage. Piso's light cavalry effectively disrupted these efforts, notably at the Battle of Ruspina when he harassed Caesar's defeated army as it retreated to its camp.[11] The two armies continued to engage in small-scale skirmishes while Caesar waited for reinforcements. Then two of the optimates' legions switched to Caesar's side. Emboldened, Caesar marched on Thapsus and besieged the city at the beginning of February 46. The optimates could not risk the loss of this position and were forced to accept battle. Scipio commanded "without skill or success",[12] and Caesar won a crushing victory which ended the war.[12]

Piso was forgiven in a general amnesty and seemed to come to terms with Caesar's victory. But when the dictator's assassination in 44 sparked the War of the Second Triumvirate he aligned himself with the assassins of Caesar, the Liberatores, joining the armies of Gaius Cassius Longinus (Cassius) and Marcus Junius Brutus the Younger (Brutus).[13] They were defeated at the hard-fought Battle of Philippi in 42, which involved 200,000 soldiers. Piso commanded troops during the campaign, but his precise role is not known. He was again pardoned and returned to Rome, where he refused to participate in the political arena which was under the control of Caesar's heir, Caesar Octavianus (the future Augustus).[4][13]

Succession crisis of 23 BC

In 23 the domination of Augustus began to cause the emperor some political difficulties, which were compounded by his apparent desire to groom his nephew Marcellus as his political heir. Problems in the political alliance between Augustus, Livia, Maecenas and Agrippa over his succession plans saw Augustus search around for potential support within the Senate.[14] With the death of the consul-elect Aulus Terentius Varro Murena prior to his assuming office, Augustus offered the consulship to the noted republican and imperial opponent Piso.[15] Becoming a consul was the highest honour of the Roman state, and as such candidates were chosen carefully by Augustus.[16]

Although Augustus clearly hoped to win Piso over, and in the process not only deflect attention away from Marcellus but also to reinforce the fiction that the republic still functioned, it is unclear why Piso accepted the role after so many years of rejecting the legitimacy of the principate. Explanations ranging from a sense of public duty, to a resurgence of his political ambitions, to resurrecting his family's dignitas after a long period of obscurity, with the hope of consulships for his two sons, have all been offered.[4]

As the year progressed, Augustus fell seriously ill. He gave up the consulship, and as his condition worsened, he began to make plans for the stability of the state should he die. Augustus handed over to his co-consul Piso all of his official documents, an account of the public finances, and authority over all troops in the provinces, declaring his intent that Piso, as consul, should take over the functioning of the state for the duration of his consulship. However, Augustus gave his signet ring to his lifelong friend the general Agrippa, a sign that Agrippa would succeed him if he were to die, not Piso.[17][18] After Augustus’ recovery, Calpurnius Piso completed the remainder of his term without incident. There is no record of his filling any other post after his consulship.[19][20]

Notes

Citations

- Broughton 1952, p. 261.

- Syme 1986, p. 330.

- Syme 1986, pp. 330, 368.

- Syme 1986, p. 368.

- Holland 2004, pp. 202–10.

- Lintott 1994, p. 52.

- Appian, The Civil Wars, 2.8–9

- Ward 1970, pp. 245–46.

- Maximus 2004, p. 204.

- Suetonius, Julius 28 Archived 2012-05-30 at Archive.today

- Goldsworthy 2006, pp. 257–59.

- Syme 1986, p. 245.

- Smith 2005, p. 375.

- Holland2004, p. 294.

- Swan 1967, p. 240.

- Mennen 2011, p. 129.

- Alston 2015, p. 248.

- Southern 2013, p. 120.

- Syme 1986, p. 384.

- Holland 2004, pp. 294–295.

Bibliography

Ancient sources

- Appianus Alexandrinus (Appian), Bellum Civile (The Civil War).

- Gaius Suetonius Tranquillus, De Vita Caesarum (Lives of the Caesars, or The Twelve Caesars).

Modern sources

- Alston, Richard (2015). Rome's Revolution: Death of the Republic and Birth of the Empire. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0190231606.

- Broughton, T. Robert S. (1952). The Magistrates of the Roman Republic, Volume II. New York: American Philological Association. OCLC 496689514.

- Goldsworthy, Adrian (2006). Caesar: Life of a Colossus. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-12048-6.

- Holland, Richard, Augustus, Godfather of Europe, (2005) Stroud: Sutton Publishing ISBN 978-0750929110

- Holland, Tom (2004). Rubicon: The Triumph and Tragedy of the Roman Republic. London: Abacus. ISBN 978-0349115634.

- Lintott, Andrew (1994). "The Roman Constitution in the Second Century B.C.". The Cambridge Ancient History, Volume 9. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 40–52. ISBN 978-0521256032.

- Maximus, Valarius (2004). Memorable Deeds and Sayings: One Thousand Tales from Ancient Rome. Translated by Henry John Walker. Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing. ISBN 9781603840712.

- Mennen, Inge (2011). Power and Status in the Roman Empire, AD 193–284. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 978-9004203594.

- Smith, William (2005). A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology. Ann Arbor, Michigan: University of Michigan Library. OCLC 612127868.

- Southern, Patricia (2013). Augustus. Abingdon, Oxon; New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-1134589562.

- Swan, Michael (1967). "The Consular Fasti of 23 B.C. and the Conspiracy of Varro Murena". Harvard Studies in Classical Philology. 71: 235–247. doi:10.2307/310766. JSTOR 310766.

- Syme, Ronald (1986). The Augustan Aristocracy. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0198148593. OCLC 440243976.

- Ward, Allen (1970). "Politics in the Trials of Manilius and Cornelius". Transactions and Proceedings of the American Philological Association. The Johns Hopkins University Press. 101: 545–556. doi:10.2307/2936071. JSTOR 2936071.

| Political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Caesar Augustus X, and Gaius Norbanus Flaccus |

Consul of the Roman Empire 23 BC with Caesar Augustus XI followed by Lucius Sestius Quirinalis Albinianus (suffect) |

Succeeded by Marcus Claudius Marcellus Aeserninus, and Lucius Arruntius |