Great Dismal Swamp

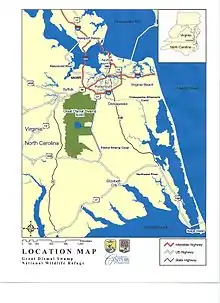

The Great Dismal Swamp is a large swamp in the Coastal Plain Region of southeastern Virginia and northeastern North Carolina, between Norfolk, Virginia, and Elizabeth City, North Carolina. It is located in parts of the southern Virginia independent cities of Chesapeake and Suffolk and northern North Carolina counties of Gates, Pasquotank, and Camden. Some estimates place the size of the original swamp at over one million acres (4,000 km2).

Lake Drummond, a 3,100-acre (13 km2) natural lake, is located in the heart of the swamp. The lake, a remarkably circular body of water, is one of only two natural lakes in Virginia. Along the Great Dismal Swamp's eastern edge runs the Dismal Swamp Canal, completed in 1805.

The Great Dismal Swamp National Wildlife Refuge was created in 1973 when the Union Camp Corporation of Franklin, Virginia, donated 49,100 acres (199 km2) of land after centuries of logging and other human activities devastated the swamp's ecosystems. The refuge was officially established through the Dismal Swamp Act of 1974, and today consists of over 112,000 acres (450 km2) of forested wetlands. Outside the boundaries of the refuge, the state of North Carolina has preserved and protected additional portions of the swamp through the establishment of the Dismal Swamp State Park. The park protects 22 square miles (57 km2) of forested wetland.[1]

A 45,611-acre (184.58 km2) remnant of the original swamp was declared a National Natural Landmark in 1973, in recognition of its unique combination of geological and ecological features.[2]

History

The origin of Lake Drummond is not entirely clear as there is no apparent network of natural streams emptying into the lake.[3]

Archaeological evidence suggests varying cultures of humans have inhabited the swamp for 13,000 years. In 1650, Algonquian-speaking Native Americans of coastal tribes lived in the swamp. In 1665, William Drummond, the first governor of North Carolina, was the first European recorded as discovering the swamp's lake, which was subsequently named for him.[4] In 1728, William Byrd II, while leading a land survey to establish a boundary between the Virginia and North Carolina colonies, made many observations of the swamp, none of them favorable; he is credited with naming it the Dismal Swamp.[4] Settlers did not appreciate the ecological importance of wetlands. In 1763, George Washington visited the area, and he and others founded the Dismal Swamp Company in a venture to drain the swamp and clear it for settlement.[5] The company later turned to the more profitable goal of timber harvesting.[6]

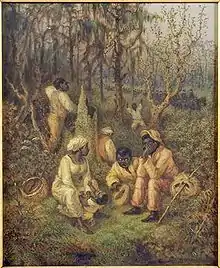

Several African-American maroon societies lived in the Great Dismal Swamp during early American history. These Great Dismal Swamp maroons consisted of escaped black refugee slaves.[7] Excavations reveal island communities existing until the Civil War.[8] Charlie, a maroon who worked illegally in a lumber camp in the swamp, later recalled that there were whole families of maroons living in the Dismal Swamp, some of whom had never seen a white man and would be terrified if they did.[9] The Underground Railroad Education Pavilion, an exhibit set up to educate visitors about the fugitive slaves who lived in the swamp, was opened February 24, 2012.[10]

The Dismal Swamp Canal was authorized by Virginia in 1787 and by North Carolina in 1790. Construction began in 1793 and was completed in 1805. The canal, as well as a railroad constructed through part of the swamp in 1830, enabled the harvest of timber. The canal deteriorated after the Albemarle and Chesapeake Canal was completed in 1858. In 1929, the United States Government bought the Dismal Swamp Canal and began to improve it. The canal is now the oldest operating artificial waterway in the country. Like the Albemarle and Chesapeake canals, it is part of the Atlantic Intracoastal Waterway.[4]

Preservation

In the mid-20th century, conservation groups across the United States began demanding the preservation of the remaining Great Dismal Swamp and restoration of its wetlands, by then understood as critical habitat for a wide variety of birds, animals, plants, and other living things. This area is along the Atlantic Flyway of migrating species. In 1973, the Union Camp Corporation, a paper company based in Franklin, Virginia, with large land holdings in the area, donated just over 49,000 acres (200 km2) of land to The Nature Conservancy, which the following year transferred the property to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.[11] During this time, a 45,611-acre (184.58 km2) portion of the swamp was declared a National Natural Landmark by the National Park Service in 1973 due to its unique combination of geological and ecological features.[2]

The Great Dismal Swamp National Wildlife Refuge was officially established by the U.S. Congress through the Dismal Swamp Act of 1974. The refuge consists of almost 107,000 acres (430 km2) of forested wetlands,[12] including the 3,100-acre (13 km2) Lake Drummond at its center.

The refuge's resource management programs aim to restore and maintain the natural biological diversity that once existed in the swamp, including its water resources, native vegetation communities, and wildlife species. Water control structures in the ditches help conserve and manage water, while forest management activities that simulate the ecological effects of wildfires are used to restore and maintain plant diversity.[11] Wildlife is managed by ensuring the presence of required habitats, with hunting used to balance some wildlife populations with available food supplies.

Today

.jpg.webp)

The Great Dismal Swamp lies wholly within the Middle Atlantic coastal forests ecoregion.[13] The swamp harbors a wide range of plant and animal species. Bald cypress, tupelo, maple, Atlantic white cypress, and pine, among other tree species found on the refuge, support the fauna within. (In a survey undertaken from 1973 to 1976, some 334 plants from 100 plant families were found.)[14] The swamp is home to many mammals, including black bears, bobcats, otters, and weasels, as well as over 70 species of reptile and amphibian. More than 200 bird species can be seen within the swamp throughout the year, including 96 nesting species.[11]

Lake Drummond is the center of activity in the swamp today, attracting fishermen, sightseers, and boaters. Camping is not allowed on the refuge.

References

- "Dismal Swamp State Park". N.C. Division of Parks & Recreation. Retrieved July 17, 2012.

- "Great Dismal Swamp". National Natural Landmarks. National Park Service. Retrieved November 19, 2016.

- Grymes, Charles A. "Lake Drummond and Great Dismal Swamp". Retrieved September 27, 2015.

- Harper, Raymond L. (2008). A History of Chesapeake, Virginia, pp. 124–28. The History Press.

- Grizzard, Frank E., Jr. (2002). George Washington: A Biographical Companion, pp. 86–87. ABC-CLIO.

- Traylor (2010), pp. 165–66.

- Kate Taylor, "The Thorny Path to a National Black Museum", The New York Times, January 22, 2011, Accessed January 31, 2011.

- Grant, Allison Shelley,Richard. "Deep in the Swamps, Archaeologists Are Finding How Fugitive Slaves Kept Their Freedom". Smithsonian. Retrieved 2019-06-25.

- Redpath, James (1859). The Roving Editor: Or, Talks with Slaves in the Southern States. New York, NY: A. A. Burdick. p. 293.

- Agnew, Tracy (24 February 2012). "Officials cut ribbon in swamp". Suffolk News Herald.

- Yarsinske, Amy Waters (2007). The Elizabeth River, pp. 328-29. The History Press.

- "Great Dismal Swamp National Wildlife Refuge". Great Outdoor Recreation Pages. Archived from the original on May 31, 2012. Retrieved July 17, 2012.

- Olson, D. M, E. Dinerstein; et al. (2001). "Terrestrial Ecoregions of the World: A New Map of Life on Earth". BioScience. 51 (11): 933–938. doi:10.1641/0006-3568(2001)051[0933:TEOTWA]2.0.CO;2. Archived from the original on 2011-10-14.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Musselman, L. J., Nickrent, D. L. & Levy, G. F. (1977) A contribution towards a vascular flora of the Great Dismal Swamp. Rhodora 79:240-268.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Great Dismal Swamp. |

| Wikisource has the text of an 1879 American Cyclopædia article about Great Dismal Swamp. |

- Great Dismal Swamp National Wildlife Refuge Official Site

- GORP's guide to The Great Dismal Swamp

- Dismal Swamp Canal Welcome Center

- Defenders of Wildlife Organization - Great Dismal Swamp page

- Bonny Blue Dismal Swamp Canal Trip

- Elizabeth City Area Convention & Visitors Bureau

- Historical and Photo Documentary of the Great Dismal Swamp

- 99% Invisible podcast on the Great Dismal Swamp

_(4578425529).jpg.webp)