Great Regression

The Great Regression refers to worsening economic conditions affecting lower earning sections of the population in the United States, Western Europe and other advanced economies starting around 1981. These deteriorating conditions include rising inequality; and falling or stagnating wages, pensions, unemployment insurance, and welfare benefits. The decline in these conditions has been by no means uniform. Specific trends vary depending on the metric being tracked, the country, and which specific demographic is being examined. For most advanced economies, the worsening economic conditions affecting the less well off accelerated sharply after the Late-2000s recession.[1][2][3]

The Great Regression contrasts with the "Great Prosperity" or Golden Age of Capitalism, where from the late 1940s to mid 1970s, economic growth delivered benefits which were broadly shared across the earnings spectrums, with inequality falling as the poorest sections of society increased their incomes at a faster rate than the richest.[1][2][3]

Examples

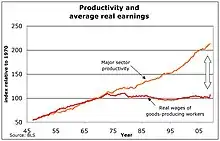

Some of the trends making up the great regression pre-date 1981. Such as stagnating wages for production and non-supervisory workers in the U.S. private sector; real wages for these workers peaked in 1973. Or the divergence in increases of productivity and pay for such workers: these two factors tended to increase in "lock-step" until about 1973, but then diverged sharply, with productivity increasing massively over the following decades, while pay stagnated. The break down of Bowley's law, the apparently near fixed proportion of economic output going to workers, is another enduring change which began around the mid 1970s.[4]

Looking at general household income, declines only became widespread in the 21st century. A McKinsey study released in 2016 and looking at 25 of the advanced economies found that only 2% of households failed to enjoy an income rise in the period from 1993 to 2005 . Yet for the period from 2005 to 2014, a much higher percentage of households saw their incomes either fall or remain stagnant: for Italy this percentage was 97%, for the U.S. 80%, 70% for G.B. & the Netherlands, and 63% for France.[5]

Looking at income growth for the bottom 90%, Australia has been something of an exception to the falling or stagnating 21st century wages affecting most advanced economies.[1]

Another exception to the acceleration in the worsening of these conditions in the 21st century appears when one looks at real hourly wage growth for U.S. workers with at most high school level education. In this case, according to a Harvard report, the decline in wages was sharper from 1979-2000 than it was from 2000-2012.[6]

Effects

Some demographic groups experiencing low incomes have suffered decreased life expectancies during the great regression. For example, a study suggested that between 1990 and 2008, white American women without high school diploma lost five years from their life expectancy, while for white American men who dropped out of high school, the loss was three years. Social scientists have not yet arrived at consensus whether these declines are caused by harsher economic conditions or to other factors such as increases in smoking or obesity.[7]

Low pay and precarious employment has been linked to increased risk of anxiety and other mental health problems. After an individual has experienced precarious employment, anxiety can persist even if they return to a permanent job.[8][9][10]

Political rage

The great regression has contributed to the so-called "politics of rage", a phenomenon associated with declining trust for centrist political parties. Political rage has seen increased support for anti-establishment and populist causes and parties, of both the right and left. While this trend has been underway for several years, it became especially high profile in 2016. Examples include support for Brexit, Donald Trump, Podemos, the Five Star Movement and AfD. While inequality and increased economic hardship has been widely accepted as a cause of political rage, including by the G20, analysts from Barclays have expressed skepticism, saying this is only "weakly supported by the available data."[11][12][13]

Causes

The great regression has been blamed on globalisation, with staff in the advanced economies facing increased competition from much less well paid workers from the developing world.[1] Professor Robert Reich however considers the main cause to be political, with the rich better able to influence politics.[2] The great regression has largely coincided with decreasing bargaining power for workers, which itself partly results from the falling influence of unions. Especially since 2013, the adverse economic trends have been increasingly blamed on technological unemployment, and with recently increased uptake of robots and automation in the emergencing economies, there are concerns that workers there too may soon suffer from the great regression.[1][4] Since 1980, under Reaganomics, there has been a decline of the progressive income tax leading to a rise in inequality.[14]

Possible end of the great regression

Data released in October 2016 found that in 2015, the trends for low earners to suffer further declines in income had reversed in the U.S., G.B. and much of continental Europe. The recent income gains for lower paid workers have been credited partly on increases in the minimum wage.[15]

See also

References

- Ed Balls , Lawrence Summers (co-chairs) (January 2015). "Report of the Commission on Inclusive Prosperity" (PDF). Center for American Progress. Retrieved July 14, 2015.

- Robert Bernard Reich (September 3, 2011). "The Limping Middle Class". New York Times. Retrieved September 6, 2011.

During periods when the very rich took home a larger proportion—as between 1918 and 1933, and in the Great Regression from 1981 to the present day—growth slowed, median wages stagnated and we suffered giant downturns. ...

- Paul Taylor (reporter) (February 7, 2011). "After the Great Recession, the Great Regression". Reuters in the New York Times. Retrieved September 6, 2011.

Wages, pensions, unemployment insurance, welfare benefits and collective bargaining are under attack in many countries as governments struggle to reduce debts swollen partly by the cost of rescuing banks during the global financial crisis.

- Ford, Martin (2015). The Rise of the Robots. One World. pp. passim, see esp. 34–41. ISBN 9781780747491.

- Larry Elliott (November 25, 2016). "Up to 70% of people in developed countries 'have seen incomes stagnate'". The Guardian. Retrieved November 27, 2016.

- Michael Porter , Jan W. Rivkin, Mihir A. Desai, Manjari Raman (November 25, 2016). "Problems Unsolved And A Nation Divided" (PDF). Harvard Business School. Retrieved November 25, 2016.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Colin Schultz (September 21, 2016). "Doctors Warned Life Expectancy Could Go Down, And It Did". Smithsonian. Retrieved November 27, 2016.

- Marlea Clarke; Wayne Lewchuk; Alice de Wolff; Andy King (2007). "This just isn't sustainable: Precarious employment,stress and workers' health". International Journal of Law and Psychiatry. 30: 311–326.

- F. Moscone; E. Tosetti; G. Vittadini (March 9, 2016). "The impact of precarious employment on mental health: The case of Italy" (PDF). Brunel University London. Retrieved November 27, 2016.

- Bill Gardner (May 4, 2016). "How to Improve Mental Health in America: Raise the Minimum Wage". The New Republic. Retrieved November 27, 2016.

- Will Martin (October 24, 2016). "These charts explain the 'Politics of Rage' — the cause of Brexit and the rise of Donald Trump". Business Insider. Retrieved November 27, 2016.

- Brendan Mulhern, NY Mellon (November 3, 2016). "Breaking down Brexit: more than just a referendum". Citywire. Retrieved November 27, 2016.

- Marvin Barth (November 7, 2016). "What investors misunderstand about the politics of rage" ((registration required)). Financial Times. Retrieved November 27, 2016.

- Sam Pizzigati and Chuck Collins (February 6, 2013). "The Great Regression. The decline of the progressive income tax and the rise of inequality". The Nation.

- Martin Sandbu (October 31, 2016). "Those elites must be doing something right" ((registration required)). Financial Times. Retrieved November 27, 2016.