Guadalupe junco

The Guadalupe junco (Junco insularis) is a small bird in the New World sparrow family that is endemic to Guadalupe Island off Pacific Mexico. Many taxonomic authorities classified it in 2008 as a subspecies of the dark-eyed junco.[1][2] In 2016, it was classified as a full species.[3]

| Guadalupe junco | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Passeriformes |

| Family: | Passerellidae |

| Genus: | Junco |

| Species: | J. insularis |

| Binomial name | |

| Junco insularis Ridgway, 1876 | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Junco hyemalis insularis Ridgway, 1876 | |

Description and ecology

This New World sparrow has a dull grayish head with a gray bill and brownish upperparts. Its wings and tail are blackish, though the tail has white edges. Its underparts are white with a rufous fringe at the bottom of the wings. It makes a high, sharp sik and a long series of chipping notes.

This bird is today found mainly in the Cupressus guadalupensis cypress grove on the island of Guadalupe, with a few birds in the remaining Guadelupe pine stands. Around 1900, it was known to utilize almost any habitat for breeding. It ranged over the whole island for feeding then, and indeed still does theoretically, but actually only a handful of flocks exist. A testimony to the adaptability of this junco is the fact that today a few birds breed at the seashore in non-native Nicotiana glauca tobacco shrub, since this is dense enough to provide some protection from cats.[4]

The breeding season is from February to June. Three to four eggs are laid in a bulky cup nest of dried grass stems, which is either in a depression in the ground or in the lower branches of a tree. The eggs are greenish-white with reddish-brown spots. If food is plentiful, the birds apparently breed twice a year.[4][5]

Decline to near-extinction

This bird used to be abundant, but now only 50–100 adult birds are thought to survive. Goats introduced to provide food for fishermen and to start a meat canning plant in the early to mid-19th century became feral and overran the island by the late 19th century, with more than four goats per hectare (nearly two per acre) being present around the 1870s.[6] Feral cats also multiplied, and as the habitat was destroyed by the goats, the cats wreaked havoc on the endemic fauna.[7] In 1897, Kaeding found the Guadalupe junco "abundant", but already decreasing due to cat predation.[5] Anthony summed up 10 years of occasional visits in 1901 by noting that "...the juncos are slowly but surely becoming scarce."[7] He blamed the interaction of goats destroying the habitat and cats destroying the birds themselves.

W. W. Brown Jr., H. W. Marsden and Ignacio Oroso surveyed Guadalupe throughout May and June 1906, and collected numerous bird specimens for the Thayer Museum – among these a "large series" of the Guadalupe junco.[8] They found the Guadalupe junco "fairly abundant" but, despite the depredations of the cats, still "a very tame, confiding little bird" – in other words, unwary of predators.

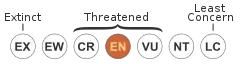

Feral goats were all but exterminated by 2006 by Grupo de Ecologia y Conservacion de Islas and Island Conservation,[9] permitting spectacular regeneration of the native flora. The island was recently protected as a biosphere reserve again by the above groups. As habitat regenerates and especially if the planned removal or containment of cats will be undertaken, the remaining Guadalupe juncos will find more protected breeding and feeding sites. Indeed, the future of the Guadalupe junco looks better than it did during the 20th century, although it is still precariously close to extinction and could be wiped out by any chance event, such as a violent storm or an introduced disease. By IUCN, it is endangered.[10]

Footnotes

- BirdLife International (2008) Guadalupe junco species factsheet. Retrieved 2008-MAY-26.

- BirdLife International (2008) 2008 IUCN Redlist status changes Archived August 28, 2007, at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 2008-MAY-23.

- Birdlife International (2016) Dark-eyed Junco (Junco hyemalis) is being split: list J. hyemalis as Least Concern and J. insularis as Endangered or Vulnerable? October 5, 2016 by James Westrip (BirdLife)

- Thayer, John E.; Bangs, Outram (1908). "The Present State of the Ornis of Guadaloupe Island" (PDF). Condor. 10 (#3): 101–106. doi:10.2307/1360977. hdl:2027/hvd.32044072250186. JSTOR 1360977.

- Kaeding, Henry B. (1905). "Birds from the West Coast of Lower California and Adjacent Islands (Part II)" (PDF). Condor. 7 (#4): 134–138. doi:10.2307/1361667. JSTOR 1361667.

- León de la Luz; José Luis; Rebman, Jon P. & Oberbauer, Thomas (2003). "On the urgency of conservation on Guadalupe Island, Mexico: is it a lost paradise?". Biodiversity and Conservation. 12 (#5): 1073–1082. doi:10.1023/A:1022854211166.

- Anthony, A.W. (1901). "The Guadalupe Wren" (PDF). Condor. 3 (#3): 73. doi:10.2307/1361475. JSTOR 1361475.

- Though this probably was barely sustainable; it certainly was far more harmful that they shot "a series of flickers" and collected six clutches of eggs of this endemic subspecies. The Guadalupe red-shafted flicker (Colaptes auratus rufipileus) became extinct about five years later.

- "- Preventing Extinctions by removing invasive species from Islands".

- BirdLife International (2016). "Junco insularis". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016: e.T22721102A104279152. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-3.RLTS.T22721102A104279152.en. Retrieved 12 January 2020.

Further reading

- Howell, Steven N. G. & Webb, Sophie (1995): A Guide to the Birds of Mexico and Northern Central America. Oxford University Press, Oxford & New York. ISBN 0-19-854012-4