Guatemala City General Cemetery

The Guatemala City General Cemetery was built in 1880, during general Justo Rufino Barrios presidency. Ruined by 1917-18 earthquakes, it never recovered its old splendor; originally it was exclusive for the elites and presidents, but gradually the eight Mayan hills that form it were invaded without any urban plan, like what happened with Guatemala City itself after the 1917-18 and 1976 earthquakes.

Cementerio General de la Ciudad de Guatemala | |

Agripina de Sánchez tomb as seen in 2014; built in 1892 is one of the most representative and best preserved of the Cemetery. | |

| Details | |

|---|---|

| Established | 1880-1883 (built) |

| Disestablished | 1917-1918 (destroyed) |

| Location | |

| Style | Renacimiento |

History

The General Cemetery was built in a place that was known as "Potrero de Garcia", which was purchased by the government of Justo Rufino Barrios in 1878. It was opened to the public in 1881 even though it was not completed yet. Within the cemetery there are eight Mayan hills that were part of Kaminal Juyú, separated from the rest of that Mayan city by a ravine. The hills surrounded and old field that might have been used to play ceremonial ball, although its space seems too long and narrow based on other ball fields found in different Maya cities.

When it was almost ready to open in 1881 most of the bodies from the San Juan de Dios Cemetery were transferred to the new one; once most of the remains had moved, the new cemetery was officially opened to the public.[4] Originally, the cemetery was built with perfect symmetry and it had an area of 20.000 m2 not counting its annex, "La Isla".[5] It had perfectly aligned streets bordered by lines of fine wood trees and luxurious tombs were built by the most important sculptors of the time. The cemetery was one of the first public buildings to have electric lights and the niches were in a solid front wall that had seven hundred and fifty meters in length.[5]

In 1882, a report presented by the secretary of the San Juan de Dios Hospital, which was in charge of the cemetery said that the hills were going to be used as a labyrinth surrounded by an outer street where the most exclusive tombs would be built.

Hill #1 was chosen by friends and family of president Justo Rufino Barrios to build his majestic tomb, which was unveiled on 2 April 1892, the seventh anniversary of his death. The inside of the Mayan hill was emptied to form the tomb. On 30 June 1894, the remains of general Miguel García Granados -former president of Guatemala- were transferred to this cemetery from his humble tomb in the old one; his new resting place was inside a majestic monument in his honor. House representative and public speaker Rafael Spinola pronounced the official speech prior to the solemn ceremony.[8]

In 1896 La Ilustración Guatemalteca published an article about the General Cemetery on November 1, Día de los Muertos; they described several tombs of famous characters of the time. Among the ones mentioned in that article that have survived earthquakes and other natural disasters are:[2] Venancio Barrios tomb, which has a sculpture of the general, recently killed by enemy fire while an angel looks into the distance;[2] general Miguel García Granados tomb and monument; and the tomb of Agripina de Sánchez, mother of former Secretary of Public Education of Justo Rufino Barrios, Delfino Sánchez.[9] At the end of their article, they describe the tomb of general Justo Rufino Barrios, which was built by his widow and children in 1892.[9]

La Ilustración also talks about a curious tomb guard by an Augustine monk who read avidly a Holy book; they only mentioned that it belong to a Belgian immigrant that made a large fortune after arriving to Guatemala.[2]

1917-1918 earthquakes

The earthquakes started on 17 November 1917 and continued on December 25 and 29 and then on 3 and 24 January 1918. In 1920, Prince Wilhelm, Duke of Södermanland arrived to Guatemala as part of a trip he was making through Central America;[10] he visited Antigua Guatemala and Guatemala City where he witnessed that both cities were in total disarray after their destruction by earthquakes in 1773 and 1917–18, respectively.[11] While Antigua Guatemala ruins were mostly abandoned since the 18th century, and were then partially inhabited by poor Indian families, Guatemala City was still filled with debris and dust from the recent earthquakes; the dust was so fine that it was impossible to avoid it from going into ones clothes, mouth, nose and even skin pores.[11] Visitors like himself developed respiratory diseases until their bodies got used to this dust. Streets did not have any pavement left and only one in three house were inhabited as the rest had been partially ruined.[11]

Public buildings, schools, churches, the theater, museums were all in the hopeless state of desolation in which they were left by the earthquake. Bits of roof hanged down the outsides of the walls and the footway was littered with heaps of stucco ornaments and shattered cornices. A payment of some hundred dollars would secure that a house that had been marked as unsecure with a black cross was then dimmed as done with its necessary repairs, allowing the owners to leave the houses empty and in ruins.[12] But it was at the cemetery that the utter devastation was most evident: all was demolished on the night of the earthquake and it was said that something like eight thousand dead were literally shaken from their graves, threatening pestilence to the city and forcing the authorities to burn all of them in a gigantic bonfire.[12] The dark cavities of the empty tombs were still opened in 1920 and no attempt had been made to restore the cemetery to its original condition.[12] The tomb guarded by the Augustine monk mentioned by Salazar in 1896 was completely destroyed and by its unique characteristics was pictured in 1918 to illustrate the effects the earthquake had on the cemetery.

Modifications to the Mayan hills

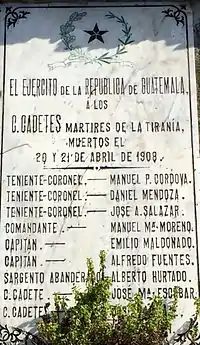

Hill #2 was cleverly used in the beginning, but it was gradually destroyed later when stairs were added to improve access to it and the monument of the cadets shot in 1908 following the assassination attempt on then president Manuel Estrada Cabrera was placed on top of it.

In 1960 a wing for the famous intellectuals that died overseas was built on Hill #5. Unfortunately, given the 1963 coup d'état against president Miguel Ydígoras Fuentes, the wing was slowly abandoned; only Antonio José de Irisarri -who died in New York in 1868 whose remains were brought back to Guatemala in 1968- and poet Domingo Estrada -who died in Paris in 1901- are interred there. Other famous writers, like Enrique Gómez Carrillo, were inscribed in a memorial on the wall given the impossibility of bringing his remains back to Guatemala. By the end of the 20th century, all the letters from the memorial had been stolen, the tombstones were marked with graffiti and the whole section was in total disarray.

2015 mudslides

On 27 May 2015 a large mudslide on the edge of the Cemetery destroyed 18 tombs, who went down a ravine which is constantly eroded by a raw sewage that flows underneath.[15] Numerous people promptly started the procedures to move their loved ones to a different location, before they lose them in another mudslide.[15] Among the monuments in peril of fall into the abyss is former president's Miguel García Granados.[15]

Famous tenants

| Name | Occupation | Brief description | Location |

|---|---|---|---|

| Árbenz Guzmán, Jacobo (1913-1971) | Army colonel and politician | Secretary of Defense during Juan José Arévalo presidency and then President of Guatemala from 1951 to 1954. [16] | Main entrance |

| Azmitia González, José | Conservative activist and Unionist leader | Had an active and decisive role in the civic unrest that lead to bring president Manuel Estrada Cabrera down on April 1920. He then continued his quest against the de facto regime of general José María Orellana and was one of the 311 citizens that requested president Jorge Ubico to resign on May 1944. | Private tomb |

| Barrios, Justo Rufino | Army general and liberal leader | President of Guatemala that tried to establish a Central American Union by force y died in the attempt.[17] When in power, stimulated Guatemalan economy by promoting coffee plantations; he accomplished this by expropriating native land and creating regulations that forced most natives to work almost for free in those plantations.[18] | Hill N.°1 |

| Castañeda de León, Oliverio (1955-1978) | Student body president | Member of the youth of communist Partido Guatemalteco del Trabajo (PGT) who strongly fought of Human Rights in Guatemala as University of San Carlos of Guatemala student body president. He was murdered by the government on 20 October 1978 in Guatemala City main square. | |

| Cerna y Cerna, Vicente (1815-1885) | Army marshall | President of Guatemala from 24 May 1865 to 29 June 1871.[19] | Main avenue |

| Colom Argueta, Manuel | Lawyer and politician | Guatemala City mayor from 1970 to 1974. He fought hardly and strongly for social justice in Guatemala but was assassinated in 1979. He was uncle of Alvaro Colom, president of Guatemala from 2008 to 2012. | |

| García Granados y Saborío, María | Socialite | Daughter of general Miguel García Granados. When she died at 18 years old, Cuban poet and hero José Martí wrote his famous poem La Niña de Guatemala in her honor.[20] | Private tomb |

| García Granados y Zavala, Miguel (1809-1878) | Army officer and liberal politician | De facto president of Guatemala between 1871 and 1873. On 27 May 2015 a mudslide at one section of the cemetery put his tomb in jeopardy.[15] | |

| Irrisarri, Antonio José de (1786-1868) | Army officer and diplomat | Died in New York City while serving as Central American Ambassador to the United States. His remains were brought back to Guatemala in 1968. | Hill#5 |

| Milla y Vidaurre, José (Salomé Jil) (1822–1882) | Historian, writer and diplomat | One the most well known and beloved writer of Guatemala.[21] | Main street |

| Ubico Castañeda, Jorge | Army officer and liberal politician | President of Guatemala from 1931 to 1944. | Private tomb |

| Zavala, José Víctor | Army Marshall and politician | Known in Guatemala as "Mariscal Zavala" and the "Guatemalan D'Artagnan", was one of the best army officers under the orders of president general Rafael Carrera. | Hill #5 |

| Zollinger, Edgar August James (1876-1898) | Farmer | British citizen of Swiss descent who killed president José María Reina Barrios on 8 February 1898.[22] | La Isla |

Notes and references

References

- Salazar & 1 November 1896, p. 96

- Asturias 1902, p. 102

- Asturias 1902, p. 185

- Spínola 1897, p. 88.

- Salazar & 1 November 1896, p. 98

- Prins Wilhelm 1922, p. 167-179.

- Prins Wilhelm 1922, p. 167.

- Prins Wilhelm 1922, p. 169.

- Sánchez, Hernández & 27 May 2015

- Sabino 2007, p. 54-68.

- Hernández de León 1930.

- Martínez Peláez 1990, p. 842.

- Gaitán 1992.

- Martínez & s.f.

- Hernández de León & 30 abril 1959.

- Fernández Ordóñez 2009.

Bibliography

- Asturias, Francisco (1902). Historia de la medicina en Guatemala (in Spanish). Guatemala: Tipografía Nacional.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- ElPeriódico (10 June 2015). "El Cementerio General, otra víctima de los derrumbes". ElPeriódico (in Spanish). Guatemala. Archived from the original on 10 June 2015. Retrieved 10 June 2015.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Fernández Ordóñez, R. (2009). Disparos en la obscuridad. El Asesinato del presidente José María Reina Barrios (in Spanish). Guatemala: Universidad Francisco Marroquín. Facultad de Educación.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gaitán, Héctor (1992). Los Presidentes de Guatemala. Guatemala: Artemis & Edinter. ISBN 84-89452-25-3.

- Hernández de León, Federico (1930). "El Libro de las efemérides" (in Spanish). Tomo III. Guatemala: Tipografía Sánchez y de Guise. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help)CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) - Martínez, M.B. (n.d.). "Viejos datos reverdecen la leyenda: Martí y la Niña" (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 20 August 2014.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Martínez Peláez, Severo (1990). "La Patria del Criollo, Ensayo de interpretación de la realidad colonial guatemalteca" (in Spanish). México: Ediciones en Marcha. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help)CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) - Navarrete Cáceres, Carlos (2001). "Evidencias arqueológicas en el Cementerio General de la ciudad de Guatemala". Anales de la Academia de Geografía e Historia de Guatemala (in Spanish). Guatemala. LXXVI.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Palmieri, Jorge (2007). "Autobiografía fotográfica". Blog de Jorge Palmieri (in Spanish). Guatemala. Retrieved 21 August 2014.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Prins Wilhelm (1922). Between two continents, notes from a journey in Central America, 1920. Londres, Inglaterra: E. Nash and Grayson, Ltd. pp. 148–209.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ramírez Rodríguez, Oscar Enrique (2009). "Profesora María Chinchilla Recinos: centenario de su nacimiento (2 September 1909-2 September 2009)" (in Spanish). Guatemala: USAID: 56. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help)CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) - Sabino, Carlos (2007). "Guatemala, la historia silenciada. 1944-1989. Parte I: Revolución y Liberación" (in Spanish). Guatemala: Fondo de Cultura Económica. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help)CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) - Salazar, Ramón A. (1 November 1896). "Una excursión al país de los muertos". La Ilustración Guatemalteca (in Spanish). Guatemala: Síguere, Guirola y Cía. I (7).CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sánchez, G.; Hernández, M. (27 May 2015). "Derrumbe en Cementerio General destruye 18 mausoleos". Prensa Libre (in Spanish). Guatemala. Retrieved 27 May 2015.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Spínola, Rafael (1897). Artículos y discursos (in Spanish). Guatemala: Tipografía Nacional. hdl:2027/inu.30000132543574.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

Media related to Guatemala City Cemetery at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Guatemala City Cemetery at Wikimedia Commons