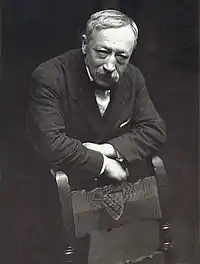

Gustave Kahn

Gustave Kahn (21 December 1859, in Metz – 5 September 1936, in Paris) was a French Symbolist poet and art critic. He was also active, via publishing and essay-writing, in defining Symbolism and distinguishing it from the Decadent Movement.

Personal life

| French literature |

|---|

| by category |

| French literary history |

| French writers |

|

| Portals |

|

Kahn was a Jew from Lorraine. He chose sides with Émile Zola in the Dreyfus affair. His wife Elizabeth converted to Judaism as a protest against anti-semitism, changing her name to Rachel.

Poetry

Kahn claimed to have invented the term vers libre, or free verse.[1] He was in any case one of the form's first European exponents. His principal publications include Les Palais nomades (1887), Domaine de fée (1895), and Le Livre d'images (1897). He also made a valuable contribution to the movement's history with his book Symbolistes et décadents (1902).

Other work

In addition to his poems, Kahn was a public intellectual who wrote novels, plays, and literary criticism. He was also extremely influential as a publisher of symbolist writing. Together with Félix Fénéon and Leo d'Orfer, both critics, Kahn founded and then directed La Vogue in 1886.[2][3] Through that magazine, Kahn and his partners were able to influence the careers of developing decadent writers such as Jules Laforgue,[2] as well as to inject new life into the careers of established figures such as Arthur Rimbaud, whose Les Illuminations manuscript was published in its pages.[4] Together with Jean Moréas, he also founded and directed Le Symboliste, a short-lived journal intended as a counter-point to Anatole Bajule's Le Décadent, which they viewed as a false and exploitative publication that represented a vain, shallow mockery of symbolist thought.[5] He played a key role in a number of other periodicals, including La Revue Indépendante, La Revue Blanche and Le Mercure de France.

He was also an art critic and collector who stayed current with developments in painting and sculpture until his death. He wrote a widely-read obituary for neo-impressionist painter Georges Seurat,[6] in which he suggested a symbolist approach to interpreting the artist's work.[7]

He also played a role in a number of debates on public issues, including anarchism, feminism, socialism, and Zionism. In the 1920s he was (head)editor of Menorah, a Jewish bimonthly magazine which folded in 1933.

In 1903, American composer Charles Loeffler set four of Kahn's poems to music for piano and voice. The poems were from Les Palais Nomades: Timbres Oublies, Adieu Pour Jamais, Les Soirs d'Automne, and Les Paons.[8]

After his death, his manuscripts were placed in the collection of the library of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

Quotation

- Les Paons

- Se penchant vers les dahlias,

- Des paons cabraient des rosaces lunaires,

- L'assouplissement des branches vénère

- Son pâle visage aux mourants dahlias.

- Elle écoute au loin les brèves musiques

- Nuit claire aux ramures d'accords,

- Et la lassitude a bercé son corps

- Au rythme odorant des pures musiques.

- Les paons ont dressé la rampe ocellée

- Pour la descente de ses yeux vers le tapis

- De choses et de sens

- Qui va vers l'horizon, parure vermiculée

- De son corps alangui.

- En l'âme se tapit

- le flou désir molli de récits et d'encens.

Principal works

- Palais nomades (1887)

- Les Chansons d'amant (1891)

- Domaine de fée (1895)

- Le Roi fou (1896)

- La Pluie et le beau temps (1896)

- Limbes de lumières (1897)

- Le Livre d'images (1897)

- Premiers poèmes (1897)

- Le Conte de l'or et du silence (1898) translated by Brian Stableford as The Tale of Gold and Silence (2011) ISBN 978-1-61227-063-0

- Les Petites Ames pressées (1898)

- Le Cirque solaire (1898)

- Les Fleurs de la passion (1900)

- L'Adultère sentimental (1902)

- Symbolistes et décadents (1902)

- Odes de la "Raison" (1902 réédité aux Editions du Fourneau 1995)

- Contes hollandais (1903)

- La Femme dans la caricature française (1907)

- Contes hollandais (deuxième série) (1908)

- La Pépinière du Luxembourg (1923)

- L'Aube enamourée (1925)

- Mourle (1925)

- Silhouettes littéraires (1925)

- La Childebert (1926)

- Contes juifs (1926 réédité chez "Les Introuvables" 1977)

- Images bibliques (1929)

- Terre d'Israël (1933)

References

- Lucie-Smith, Edward. (1972) Symbolist Art. London: Thames & Hudson, p. 58. ISBN 0500201250

- Everdell, William R. (1998). The First Moderns: Profiles in the Origins of Twentieth-Century Thought. University of Chicago. pp. 80. ISBN 9780226224817.

- Dorra, Henri (1994). Symbolist Art Theories: A Critical Anthropology. University of California. p. 127. ISBN 0520077687.

- Kearns, James (1989). Symbolist Landscapes: The Place of Painting in the Poetry and Criticism of Mallarmé and His Circle. MHRA. p. 129. ISBN 094762323X – via Google Books.

- Somigili, Luca (2003). Legitimizing the Artist: Manifesto Writing and European Modernism, 1885-1915. University of Toronto. ISBN 1442657731.

- Kahn, Gustave (1891). "Seurat". L'Art Moderne. 11: 107–110.

- Young, Marnin (2012). "The Death of Georges Seurat: Neo-Impressionism and the Fate of the Avant-Garde in 1891". RIHA: Journal of the International Association of Research Institutes in the History of Art. 0043.

- Loeffler, Charles Martin (1903). Quatre mélodies pour chant et piano. Poésies de Gustave Kahn. G. Schirmer – via Hathi Trust.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Gustave Kahn. |

| Wikisource has the text of a 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article about Gustave Kahn. |