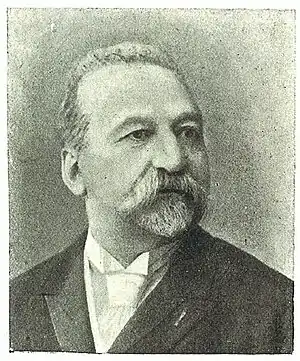

Gustave Trouvé

Gustave Pierre Trouvé (2 January 1839 – 27 July 1902) was a French electrical engineer and inventor in the 19th century.

Gustave Trouvé | |

|---|---|

Gustave Trouvé

| |

| Born | 2 January 1839 |

| Died | 27 July 1902 (aged 63) |

| Nationality | French |

| Alma mater | Ecole des Arts et Métiers, Angers |

| Known for | The above fields |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Electrical engineering, Multiple Applications - Transport, Medical, Entertainment, Inventor |

Trouvé was born on 2 January 1839 in La Haye-Descartes (Indre-et-Loire, France) and died on 27 July 1902 in Paris. A polymath, he was highly respected for his innovative skill in miniaturization.

Youth

Gustave Trouvé was born into a modest family, his father, Jacques Trouvé, was a cattle dealer.[1] In 1850, he studied to be a locksmith in Chinon College, then in 1854-55 at the École des Arts et Métiers in Angers.[2] His studies incomplete through poor health, he left his local region for Paris where he obtained a job with a clockmaker.[3]

Paris

From 1865 Trouvé set up a workshop in central Paris where he innovated and patented many widely differing applications of electricity, regularly reported on by popular science magazines of the time such as La Nature.[4] He invented a carbon-zinc pocket-sized battery to power his miniature electric automata which soon became very popular. [5] [6] A similar battery was invented and widely commercialized by Georges Leclanché.

The 1870s

Gustave Trouvé took part in the improvement in communication systems with several noteworthy innovations. In 1872 he developed a portable military telegraph whose cabling enabled rapid communication up to a distance of one kilometer, enabling the swift transmission of both orders and reports back from the Front.[7] In 1874, he developed a device for locating and extracting metal objects such as bullets from human patients, the prototype of today’s metal detector.[8] In 1878, he improved the sound intensity of Alexander Graham Bell’s telephone system by incorporating a double membrane. The same year he invented a highly sensitive portable microphone. Trouvé soon came to be known and respected by his talent for miniaturization. The same year, using a battery developed by Gaston Planté, and a small incandescent airtight bulb, he innovated a "polyscope", the prototype of today’s endoscope.[9]

The 1880s

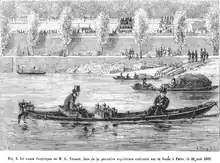

In 1880 Trouvé improved the efficiency of a small electric motor developed by Siemens and using the recently developed rechargeable battery, fitted it to an English James Starley tricycle, so inventing the world’s first electric vehicle.[10] Although this was successfully tested on 19 April 1881 along the Rue Valois in central Paris, he was unable to patent it.[11] Trouvé swiftly adapted his battery-powered motor to marine propulsion; to make it easy to carry his marine conversion to and from his workshop to the nearby River Seine, Trouvé made it portable and removable from the boat, thus inventing the outboard engine.[12] On 26 May 1881 the 5m Trouvé prototype, called Le Téléphone reached a speed of 1 m/s (3.6 km/h) going upstream at 2.5 m/s (9 km/h) downstream.[13]

Trouvé exhibited his boat (but not his tricycle) and his electro-medical instruments at the International Electrical Exhibition in Paris and soon after was awarded the Légion d'Honneur.[14] He also miniaturized his electric motor to power a model airship, a dental drill, a sewing machine and a razor.[15][16]

Gustave Trouvé next invented his "Photophore", or battery-powered frontal headlamp, which he developed for a client, Dr Paul Hélot, an ear-nose-and throat specialist of Rouen. This wearable, direct shaft, lighting system could be oriented by head movements, so freeing the hands of its wearer. A file of correspondence between these two men enables one to place this invention during 1883. Trouvé soon modified their frontal headlamp both for use by miners, rescue workers, and later by speleologists, in dark surroundings, but also by tinting the light with various colors as theater jewelry for artiste troupes in Paris and Europe. The latter became known as "luminous electric jewels" and was the forerunner of today's wearable technology.[17]

In 1884, Trouvé fitted an electric boat with both electric horn and a bow-mounted frontal headlamp, the first time such electrical accessories had ever been fitted on any mode of transport.[18] He developed a portable electric safety lamp.[19] In 1887, Trouvé, whose brand name was Eureka (Greek: εὕρηκα =“I have found”, translated into French “J’ai trouvé), developed his auxanoscope, an electric slide projector for itinerant teachers (1887). Around the same period, Trouvé, a confirmed bachelor uninterested in commercialization, turned his fertile mind skywards. Convinced that the future lay with heavier-the-air machines, he flew a tethered model electric helicopter, the ancestor of the Sikorsky Firefly.

He next built an ornithopter, the wings of which flapped using a rapid succession gun cartridges, enabling it to make a noisy but at the time unheard-of flight of 80 meters.[20]

In 1889, he also fitted the battery-electric rifle he had developed in 1866, with a frontal light enabling nocturnal hunting. He also developed a battery-electric alarm system for nocturnal fishing.

The 1890s

In 1891 Trouvé developed electric multi-colored fountains for domestic and outdoor use. Seeing the limitations of electrical supply without the reliable support of a national grid, in 1895 he took the recent discovery of acetylene light and had soon harnessed it for domestic lighting.[21] Among his 75 innovations,(see below) he also developed an electric massaging machine, an electric keyboard instrument based on Savart's wheel, a battery-powered wearable lifejacket, a water-jet propelled boat and a streamlined bicycle, as well as several children's toys.

In 1902, Trouvé was working on his latest innovation, a small portable device which used ultra-violet light to treat skin diseases, the prototype of PUVA therapy when he accidentally cut his thumb and index finger. Neglecting the wound, sepsis set in and after amputations at the Saint-Louis Hospital, Paris, the 63-year-old inventor died on 27 July 1902.

Disappearance and rehabilitation

When the obligatory concession for his tomb in the cemetery of his native town of Descartes was not renewed, Trouvé’s remains were thrown into the common grave. His archives were destroyed in February 1980 during an accidental fire in the Town Hall. In 2012, following a French biography by English transport historian Kevin Desmond, a commemorative plaque was officially unveiled on the site of his birthplace. Four years later, following an extended English-language biography, on 15 October 2016, a second plaque was officially unveiled by Desmond and Jacques Boutault, Mayor of Paris 2nd District, on the wall outside his former workshop, 14 rue Vivienne. The search for rare surviving examples of his instruments has become worldwide. On 24 September a Trouvé/Cadet-Picard gold skull stick pin automaton sold at Bonhams of London for $8,000.[22] An exhibition celebrating the 180th anniversary of his birth, entitled "Gustave Trouvé, the da Vinci of the 19th Century", took place at his birthplace in Descartes, France during the month of May 2019. Sixteen of his original instruments were brought together, while a line-up of modern electric cars, boats, drones and bicycles were assembled in his honour. In 2020, A Canadian website Plugboats.com launched a competition to vote online for the best electric boats of the year calling it the Gustave Trouvé Award. The medals portraying Trouvé were called the Gussies (Gustave). Over 4,000 people voted between May and July 2020.

Inventions and innovations in chronological order

1864 Electro-spherical Geissler tube motor

1865 The Lilliputian sealed battery

1865 Electro-medical apparatus

1865 Electro-mobile jewelry

1865 Electric gyroscope

1866 Electric rifle

1867 Electro-medical kit

1869 Liquid-fuelled pantoscope

1870 Device imitating the flight of birds

1872 Portable Military Telegraph

1873 Improved dichromate battery

1874 Explorer-extractor of bullets

1875 Electric almanac or calendar

1875 Portable Dynamo-electric machine

1875 Oxygen spacesuit for balloonists

1877 Simulation of muscle contraction

1877 Electric paperweight

1878 Exploratory polyscopes for cavities of the human body

1878 Telephones and improvement of the microphone

1880 Improved Siemens motor

1881 Manufacture of magnets

1881 Luminous electric jewels

1881 Electric boat

1881 Miniaturized dental drill

1881 Marine outboard motor

1881 Electric tricycle

1883 Underwater lighting.

1883 Trouvé-Hélot frontal headlamp

1883 Electric vehicle headlamp

1884 Electric safety lamp

1885 Electrical apparatus for lighting physiology and chemistry laboratories

1885 Underwater lighting used during the Suez Canal

1886 New system for constructing propellers

1886 Electric siren as an alarm signal

1887 Working model electric helicopter (tethered)

1887 Electric auxanoscope (image projector)

1889 Electric counter

1889 Dynamo electric demonstrator

1889 Improvements to the electric rifle

1889 System for transporting plate glass sheets

1890 Universal dynamometer

1890 Electric lighting for horse-drawn carriages

1890 Electric orygmatoscope for the inspection of geological layers.

1890 Mobile electric-pneumatic streetlamp lighter

1891 Second mechanical bird

1891 Improvements in luminous electric fountains

1892 Electric trigger mechanism for time-lapse photography

1892 Hand-held medical dynamometer

1892 Battery-electric massage instrument for hernia

1893 Electric industrial ventilation system

1894 System for automatic fishing by night.

1894 Electric stunning lance for hunting

1894 Luminous electric jewelry belt

1894 Electric keyboard instrument based on Savart’s wheel

1894 Luminous electric jumping rope

1895 Acetylene domestic lighting

1895 Universal AC/DC electric motor

1895 Improved pedal bicycle

1895 Manual/electric hybrid massaging machine

1897 Device for automatic bottling of acetylene

1897 Device for hermetically sealing containers of acetylene

1897 Windmill toy for hats and canes

1898 Multi-task manual-electric industrial gyratory pump

1899 Carburetor for internal combustion engines

1900 Battery electric inflatable wearable lifejacket

1901 Binoculars for the Navy

1901 Phototherapy instruments

1902 Spring-loaded harpoon gun toy

1902 Propulsion of model boat or submarine by acetylene

References

- George Barral, "L’histoire d’un inventeur: Exposé des découvertes et des travaux de M. Gustave Trouve dans le domaine de l’électricité" (Paris: Georges Carré, 1891)

- Reference ETP 812, Departmental Archives of Maine-et-Loire

- Archives de la Ville de Paris

- La télégraphie militaire (military telegraphy), La Nature, 1876

- Trouvé's bijoux électriques lumineux. http://cnum.cnam.fr/CGI/fpage.cgi?4KY28.13/233/100/436/0/0

- Abbé Moigno, Les Mondes, Volume xxxx, n° 14, 1st August 1878

- "CNUM - Erreur".

- Le XIXe Siècle 12 August 1874

- Ségal,Alain, « Place de l’Ingénieur Gustave Trouve dans l’histoire de l’endoscopie », TOME XXIX, Histoire des Sciences Médicales, Organe Officiel de la Société Française d’Histoire de la Médecine, n° 2, http://www.biusante.parisdescartes.fr/sfhm/hsm/HSMx1995x029x002/HSMx1995x029x002x0123.pdf 1995

- Ernest Henry Wakefield, History of the Electric Automobile, 540 pp, Society of Automobile Engineers, USA , 1993.

- La Nature, 16 April 1881

- Desmond, "A Century of Outboard Racing", Van de Velde Maritime. 2000.

- Communication made by Trouvé to the Académie des Sciences de Paris, 1881

- Pantheon of the Legion d’Honneur, January 1882

- Exposition Internationale de l’Electricité 1881, Administration-jury-rapports, Tome Premier, 1883, Paris

- Publicity, « Overview of the prices of Trouvé luminous electric jewels, the sole inventor patented in France and abroad », in l’Electricité au theatre, bijoux électromobiles, 1885.

- Overview of the prices of Trouvé luminous electric jewels, the sole inventor patented in France and abroad, in l’Electricité au theatre, bijoux électromobiles, 1885.

- Letter from G Trouvé to Paul Hélot, 25 July 1883

- Trouvé, Lampes électriques portatives, communication to the Académie des Sciences, November 10, 1884

- Mémoire presented by G. Trouvé, on 24 August 1891. Conserved at the Académie des Sciences, Paris, reference arch-2007/26.

- Journal mensuel de l’Académie nationale de l’Industrie agricole manufacturière et commerciale, December 1895.

- "Fine Jewellery" Bonhams London Thursday 24 September 2015

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Gustave Trouvé. |

- Biography "Gustave Trouvé French Electrical Genius (1839–1902)" - McFarland Books - Author: Kevin Desmond

- Biography "A la recherche de Trouvé" - Pleine Page éditeur - Author: Kevin Desmond

- Trouvé dedicated website: http://www.gustave-trouve-eureka.com