Gwisho Hot-Springs

Gwisho hot-springs is a rare site for its large quantity of preserved animal and plants remains, located in Lochinvar National Park, Zambia. The site was first excavated by J. Desmond Clark in 1957, who found faunal remains and quartz tools in the western end of the site.

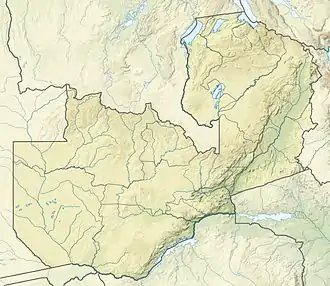

Shown within Gwisho Hot-Springs | |

| Location | Lochinvar National Park, Zambia |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 15°59′12.0″S 27°14′30.9″E |

Creighton Gabel excavated the same area in 1960-1961 and more of Gwisho hot-springs was excavated in 1963-1964. It provided an abundance of economic and technological evidence that is without equal anywhere in South Africa. Gwisho hot-springs has a become of a significance importance to African prehistory.[1][2]

Location

The Gwisho hot-springs is located on Lochinvar Lodge in Lochinvar National Park, Zambia; it extends over 1.5 km (0.93 mi) on the south edge of the Kafue Flats, 61.1 km (38.0 mi) southwest of Monze, and about 1 km (0.62 mi) west of the Lochnivar Ranch.

Environment

Gwisho hot-springs is in a shallow fault-determined valley with large amounts of alluvia and sand deposits, they’re located 977 m (3,205 ft) above sea-level. Within the valley there are several cold and hot water spring; most of the hot springs are sulphurous and many of them contains dissolved chloride.

The Kafue Flats is a seasonal floodplain created by the Kafue River, located 22.5 km (14.0 mi) south of Gwisho. It is flat and mostly featureless with low grass cover. 11.3 km (7.0 mi) south of the river, the ground rises slightly and the topography is less monotonous. The landscape is covered with anthills, bushes, and Acacia trees. Denser woodland is found where the soils are deeper.

4.8 km (3.0 mi) from the southern boundary of Lochnivar: older rocks created from the alluvial deposits and a higher plateau surface with low hills.

The hot-springs are located between the plain and higher ground. Several types of trees grow along the spring line, including Comebretum imberbe, Sclerocarya caffra, Lonchocarpus capassa, Acacia sierberiana, and Acacia nigrescens.

The vegetation south of the hot-springs includes Albizia harveyi, Acacia campylacantha, Combretum inberbe, Piliostigma thonningii, and Acacia giraffe.

Stratigraphy

The trenches excavated in the site are made of sterile white sand and gravel bedrock overlain by a band of sterile brown clay and a layer of black, greasy soil of varying thickness. It contains no implements. The sterile zones of Gwisho are sealed by a horizon of dark grey, heavy soil with lenses of grey-brown deposit. Organic remains can be found in these horizons. The black, greasy, sterile soil varies in thickness from 15.2 to 22.9 cm.[3]

In Upslopes, the upper levels consist of yellow-brown and brown soils and contains 61 cm of yellow-brown sandy clay contains stone implements.

Soil samples collected from the site consists mostly of quartz sand grains with angular profiles, most likely of alluvial origin. Calcium carbonate was also found and a sample was rich in organic material.

Dating

Radiocarbon samples from the site determines the age of artifacts and human activity. J.C. Vogel of the Natuurkundig Laboratorium dated three samples, a piece of wood and grass layer from a hut or wind-break dates back to 1710 BCE, a charcoal sample dates back to 1730 BCE, and twigs dates back around 2835 BCE. Radiocarbon dates place human activity in the area between 2750 and 2340 BCE. Matopo Hill sites have yield samples that revealed how long hunter-gatherers lived in the area. The lower Wilton at Amadzimba cave gave a reading of 2250 BCE, however the Pomongwe Late Stone Age dates show earlier activity. Dates from Dombozanga cave, 730 CE, Magabengberg, 941 CE, and Lusu, 186 BCE, confirms that Late Stone Age people continued to flourish as late as the earlier centuries of the Iron Age.

Finds

Remains were found that seems to have been a hut or windbreak as well as sticks and twigs and a mass of grass lay in a flattened heap. All the grass and wood had been stripped of their roots. Tiny fragments of fired clay excavated from the site may have been used for windbreaks to smear huts and other structures. Blades and bladelets were excavated with primary flakes. Microlith and macrolith industries were discovered in the area as well as wooden tools.

Large numbers of fragmentary bones had been excavated from the Gwisho sites. The bones were well preserved, with fresh edges and spongy structures. The remains belong to buffalo, lechwe, wildebeest, impala, buchduck, kudu, eland, oribi roan, hartebeest, grysbuck, duiker, zebra, warthog, bushpig, elephant, rhinoceros, hippopotamus, monkey, baboon, birds, tortoise. None of these animal findings are surprises since all the species are, or were common in the area of Gwisho. Ivory and fresh-water shells were found along with shell beads.

Wooden artifacts and fibers were preserved under favorable conditions. Types of wood include Baikiaea, Dalbergia, Brachystegia, and Celtis. The hunters of Gwisho had at least three vegetation zones near their camps.

Culture

The hunting methods of the Gwisho’s hunters were probably similar to those used by modern San. Many arrowheads and link shafts were excavated from the site, indicating the use of the bow and arrow.[4] They also used spears as a hunting tool. Another method employed by the Gwisho inhabitants was the use of snares and traps. Animals could have been driven into swampy or scalding hot-parts of the hot-springs and then killed off. It is possible that the springs were fitted with devices for trapping and the scalding hot water could have been used to kill animals.

Barbel was the easiest fish to catch and most of the fish bones found were those of barbels. They could have been speared in the shallows or trapped in shallow pools. Since no fishing artifacts were found at the Gwisho sites, the latter method of trapping the fish in shallow pools was most likely used since it is a technique that does not require great amount of skill.[5]

Despite the findings of four fragments of stone that appeared to be of foreign origin, there were no findings of traded objects. The inhabitants were self-sufficient with the raw materials already present in Gwisho and there was little or no need for trading.

Human remains

At the Gwisho site of Kafue Flats, more than thirty burials were found and skeletons showed Khoisan features. In terms of morphology, the Gwisho people may have been physically divergent from modern San.[6]

References

- Fagan and Van Noten (1971). The Hunter-Gatherers of Gwisho. p. 3.

- Gabel, Creighton (1965). Stone Age hunters of the Kafue: the Gwisho A site. No. 6. Africana Pub.

- Fagan and Van Noten (1971). The Hunter-Gatherers of Gwisho. p. 17.

- Connah (2004). Forgotten Africa. pp. 22–24.

- Fagan and Van Noten (1971). The Hunter-Gatherers of Gwisho. p. 59.

- Mitchell and Lane (2013). The Oxford Handbook of African Archaeology. p. 474.

- Connah, Graham (2004), Forgotten Africa: An Introduction to its archeology, Routledge, ISBN 978-0-415-30591-4

- Fagan, Brian F. and Van Noten, Francis (1971), The Hunter-Gatherers of Gwisho, Musee Royal De L'Afrique Centrale

- Mitchell Peter and Lane, Paul (2013), The Oxford Handbook of African Archaeology, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-956988-5