H. P. Lovecraft

Howard Phillips Lovecraft (US: /ˈlʌvkræft/; August 20, 1890 – March 15, 1937) was an American writer of weird and horror fiction, who is known for his creation of what became the Cthulhu Mythos.[n 1]

H. P. Lovecraft | |

|---|---|

Lovecraft in 1934 | |

| Born | Howard Phillips Lovecraft August 20, 1890 Providence, Rhode Island, United States |

| Died | March 15, 1937 (aged 46) Providence, Rhode Island, United States |

| Resting place | Swan Point Cemetery, Providence, Rhode Island, U.S. 41.854021°N 71.381068°W |

| Pen name |

|

| Occupation | Short story writer, editor, novelist, poet |

| Period | 1917–1937 |

| Genre | Weird fiction, horror fiction, science fiction, gothic fiction, fantasy, Lovecraftian horror |

| Literary movement | Cosmicism |

| Notable works | |

| Spouse | |

| Signature | |

Born in Providence, Rhode Island, Lovecraft spent most of his life in New England. He was born into affluence, but his family's wealth dissipated soon after the death of his grandfather. In 1913, he wrote a critical letter to a pulp magazine that ultimately led to his involvement in pulp fiction. During the interwar period, he wrote and published stories that focused on his interpretation of humanity's place in the universe. In his view, humanity was an unimportant part of an uncaring cosmos that could be swept away at any moment. These stories also included fantastic elements that represented the perceived fragility of anthropocentrism.

Lovecraft joined the small "Kalem Club" of writers when he first moved to New York, and would later be the center of a wider body of authors known as the "Lovecraft Circle." This group wrote stories that frequently shared details among them. He was also a prolific letter writer. He maintained a correspondence with several different authors and literary proteges. According to some estimates, he wrote approximately 100,000 letters over the course of his life.[n 2] In these letters, he discussed his worldview and his daily life, and tutored younger authors, such as August Derleth, Donald Wandrei, and Robert Bloch.

Throughout his adult life, Lovecraft was never able to support himself from earnings as an author and editor. He was virtually unknown during his lifetime and was almost exclusively published in pulp magazines before he died in poverty at the age of 46, but is now regarded as one of the most significant 20th-century authors of supernatural horror fiction. Among his most celebrated tales are "The Call of Cthulhu", "The Rats in the Walls", At the Mountains of Madness, The Shadow over Innsmouth, and The Shadow Out of Time. His writings form the basis of the Cthulhu Mythos, which has inspired a large body of pastiches across several mediums drawing on Lovecraft's characters, setting and themes, constituting a wider subgenre known as Lovecraftian horror.

Biography

Early life and family tragedies

Lovecraft was born in his family home on August 20, 1890, in Providence, Rhode Island. He was the only child of Winfield Scott Lovecraft and Sarah Susan [née Phillips] Lovecraft.[3] Susie's family was of substantial means at the time of their marriage, her father, Whipple Van Buren Phillips, being involved in business ventures.[4]

In April 1893, after a psychotic episode in a Chicago hotel, Winfield was committed to Butler Hospital in Providence. Though it is not clear who reported Winfield's prior behavior to the hospital, medical records indicate that he had been "doing and saying strange things at times" for a year before his commitment.[5] Winfield spent five years in Butler before dying in 1898. His death certificate listed the cause of death as general paresis, a term synonymous with late-stage syphilis.[6] Throughout his life, Lovecraft maintained that his father fell into a paralytic state, due to insomnia and being overworked, and remained that way until his death. It is not known whether Lovecraft was simply kept ignorant of his father's illness or whether his later remarks were intentionally misleading.[5]

After his father's hospitalization, Lovecraft resided in the family home with his mother, his maternal aunts Lillian and Annie, and his maternal grandparents Whipple and Robie.[7] According to the accounts of family friends, Susie doted on the young Lovecraft to a fault, pampering him and never letting him out of her sight.[8] Lovecraft later recollected that after his father's illness his mother was "permanently stricken with grief." Whipple became a father figure to Lovecraft in this time, Lovecraft noting that his grandfather became the "centre of my entire universe." Whipple, who traveled often on business, maintained correspondence by letter with the young Lovecraft who, by the age of three, was already proficient at reading and writing.[7]

He encouraged the young Lovecraft to have an appreciation of literature, especially classical literature and English poetry. In his old age he helped raise the young H. P. Lovecraft and educated him not only in the classics, but also in original weird tales of "winged horrors" and "deep, low, moaning sounds" which he created for his grandchild's entertainment. The exact sources of Phillips' weird tales have not been identified. Lovecraft himself guessed that they originated from classic Gothic novelists like Ann Radcliffe, Matthew Lewis, and Charles Maturin. It was in this period that Lovecraft was introduced to some of his earliest literary influences such as The Rime of the Ancient Mariner illustrated by Gustave Doré, One Thousand and One Nights, a gift from his mother, Thomas Bulfinch's Age of Fable and Ovid's Metamorphoses.[9]

While there is no indication that Lovecraft was particularly close to his grandmother Robie, her death in 1896 had a profound effect. By his own account, it sent his family into "a gloom from which it never fully recovered." His mother's and aunts' wearing of black mourning dresses "terrified" him, and it is at this time that Lovecraft, approximately five-and-a-half years old, started having nightmares that would inform his later writing. Specifically, he began to have recurring nightmares of beings he termed "night-gaunts"; their appearance he credited to the influence of Doré's illustrations, which would "whirl me through space at a sickening rate of speed, the while fretting & impelling me with their detestable tridents." Thirty years later, night-gaunts would appear in Lovecraft's writing.[10]

Lovecraft's earliest known literary works began at age seven with poems restyling the Odyssey and other mythological stories.[11] Lovecraft has said that as a child he was enamored of the Roman pantheon of gods, accepting them as genuine expressions of divinity and foregoing his Christian upbringing. He recalled, at five years old, being told Santa Claus did not exist and retorting by asking why "God is not equally a myth."[12] At the age of eight, he took a keen interest in the sciences, particularly astronomy and chemistry. He also examined the anatomy books available to him in the family library, learning the specifics of human reproduction that had yet to be explained to him, and found that it "virtually killed my interest in the subject."[13]

In 1902, according to Lovecraft's own correspondence, astronomy became a guiding influence on his world view. He began producing the periodical Rhode Island Journal of Astronomy, of which 69 issues survive, using the hectograph printing method.[14] Lovecraft went in and out of elementary school repeatedly, oftentimes with home tutors making up for those lost school years, missing time due to health concerns that are not entirely clear. The written recollections of his peers described him as both withdrawn yet openly welcoming to anyone who shared his current fascination with astronomy, inviting anyone to look through the telescope he prized.[15]

By 1900, Whipple's various business concerns were suffering a downturn and slowly reducing his family's wealth. He was forced to let his family's hired servants go, leaving Lovecraft, Whipple, and Susie, being the only unmarried sister, alone in the family home.[16] In the spring of 1904, Whipple's largest business venture suffered a catastrophic failure. Within months, he died due to a stroke at age 70. After Whipple's death, Susie was unable to support the upkeep of the expansive family home on what remained of the Phillips' estate. Later that year, she was forced to move herself and her son to a small duplex.[17]

Lovecraft has called this time one of the darkest of his life, remarking in a 1934 letter that he saw no point in living anymore.[18] In fall of the same year, he started high school. Much like his earlier school years, Lovecraft was at times removed from school for long periods for what he termed "near breakdowns." He did say, though, that while having some conflicts with teachers, he enjoyed high school, becoming close with a small circle of friends and performed well academically, excelling in particular at chemistry and physics.[19] Aside from a pause in 1904, he also resumed publishing the Rhode Island Journal of Astronomy as well as starting the Scientific Gazette, which dealt mostly with chemistry.[20] It was also during this period that Lovecraft produced the first of the types of fiction he would later be known for, namely "The Beast in the Cave" and "The Alchemist".[21]

It was in 1908, prior to his high school graduation, when Lovecraft suffered another health crisis of some sort, though this instance was seemingly more severe than any prior. The exact circumstances and causes remain unknown. The only direct records are Lovecraft's own later correspondence wherein he described it variously as a "nervous collapse" and "a sort of breakdown," in one letter blaming it on the stress of high school despite his enjoying it. In another letter concerning the events of 1908, he notes, "I was and am prey to intense headaches, insomnia, and general nervous weakness which prevents my continuous application to any thing."[22]

Though Lovecraft maintained that he was to attend Brown University after high school, he never graduated and never attended school again. Whether Lovecraft suffered from a physical ailment, a mental one, or some combination thereof has never been determined. An account from a high school classmate described Lovecraft as exhibiting "terrible tics" and that at times "he'd be sitting in his seat and he'd suddenly up and jump." Harry Brobst, a psychology professor, examined the account and claimed that chorea minor was the most likely cause of Lovecraft's childhood symptoms while noting that instances of chorea minor after adolescence are very rare.[22]

Lovecraft himself acknowledged in letters that he suffered from bouts of chorea as a child.[23] Brobst further ventured that Lovecraft's 1908 breakdown was attributed to a "hysteroid seizure," a term that today usually denotes atypical depression.[24] In another letter concerning the events of 1908, Lovecraft stated that he "could hardly bear to see or speak to anyone, & liked to shut out the world by pulling down dark shades & using artificial light."[25]

Earliest recognition

Few of Lovecraft and Susie's activities from late 1908 to 1913 are recorded.[25] Lovecraft mentions a steady continuation of their financial decline highlighted by a failed business venture of his uncle that cost Susie a large portion of their dwindling wealth. A friend of Susie, Clara Hess, recalled a visit during which Susie spoke continuously about Lovecraft being "so hideous that he hid from everyone and did not like to walk upon the streets where people could gaze on him." Despite Hess' protest that this was not the case, Susie maintained this stance.[26] For his part, Lovecraft said he found his mother to be "a positive marvel of consideration".[27] A next-door neighbor later pointed out that what others in the neighborhood often supposed were loud, nocturnal quarrels between mother and son, she recognized as being recitations of Shakespeare, an activity that seemed to delight mother and son.[28]

During this period, Lovecraft revived his earlier scientific periodicals.[25] He endeavored to commit himself to the study of organic chemistry, Susie buying the expensive glass chemistry assemblage he wanted.[29] Lovecraft found his studies were hobbled by the mathematics involved, which he found boring and would cause headaches that would incapacitate him for a day.[30] Lovecraft's first poem that was not self-published appeared in a local newspaper in 1912. Called Providence in 2000 A.D., the poem envisioned a future where American of English descent were displaced by immigrants: Irish, Italians, Portuguese, and Jews.[31] In this period he also wrote racist poetry such as "New-England Fallen" and "On the Creation of Niggers"; there is no indication that either were ever published in his lifetime.[32]

In 1911, Lovecraft's letters to editors began appearing in pulp and weird-fiction magazines, most notably Argosy.[33] A 1913 letter critical of Fred Jackson, a prominent writer for Argosy, started Lovecraft down a path that would greatly affect his life. Lovecraft described Jackson's stories as "trivial, effeminate, and, in places, coarse." Continuing, Lovecraft said that Jackson's characters exhibit the "delicate passions and emotions proper to negroes and anthropoid apes."[34]

This sparked a nearly year-long feud in the letters section of Argosy between Lovecraft, along with his occasional supporters, and the majority of readers critical of his view of Jackson. Lovecraft's biggest critic was John Russell, who often replied in verse, and to whom Lovecraft felt compelled to reply because he respected Russell's writing skills.[34] The most immediate effect of the feud was the recognition garnered from Edward F. Daas, then head editor of the United Amateur Press Association[35] (also known as the UAPA). Daas invited Russell and Lovecraft to the organization and both accepted, Lovecraft in April 1914.[36]

Rejuvenation and tragedy

—Lovecraft in 1921.[37]

Lovecraft immersed himself in the world of amateur journalism for most of the following decade.[37] During this period, he was an advocate for amateurism versus commercialism.[38] Lovecraft's definition of commercialism, though, was specific to writing for, what he considered, low-brow publications for pay. He contrasted this with his view of "professional publication," which he termed as writing for journals and publishers he considered respectable. He thought of amateur journalism as training and practice for a professional career.[39]

Lovecraft was appointed chairman of the Department of Public Criticism of the UAPA in late 1914.[40] He used this position to advocate for his, what many considered peculiar, insistence on the superiority of English language usage that most writers already considered archaic. Emblematic of the Anglophile opinions he maintained throughout his life, he openly criticized other UAPA contributors for their "Americanisms" and "slang." Often these criticisms were couched in xenophobic and racist arguments bemoaning the "bastardization" of the "national language" by immigrants.[41]

In mid-1915, Lovecraft was elected to the position of first vice-president of the UAPA.[42] Two years later, he was elected president and appointed other board members that mostly shared his view on the supremacy of classical English over modern American English.[43] Another significant event of this time was the beginning of World War I. Lovecraft published multiple criticisms of the U.S. government's and the American public's reluctance to join the war to protect England, which he viewed as America's homeland.[44]

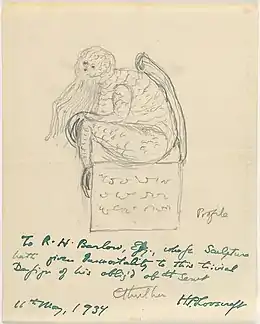

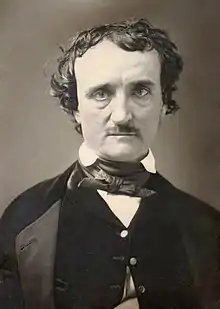

In 1916, Lovecraft published his early short story "The Alchemist" in the main UAPA journal, a departure from his usual verse. Due in no small part to the encouragement of W. Paul Cook, another UAPA member and future lifelong friend, Lovecraft began writing and publishing more fiction.[45] Soon to follow were "The Tomb" and "Dagon".[46] "The Tomb", by Lovecraft's own admission, follows closely the style and construction of the writings of one of his largest influences, Edgar Allan Poe.[47] "Dagon" though, is considered Lovecraft's first work that embraced the concepts and themes that his writing would later be known for.[48]

In 1918, Lovecraft's term as president of the UAPA elapsed, and he took his former post as chairman of the Department of Public Criticism.[49] In 1919, Lovecraft published another short story, "Beyond the Wall of Sleep".[50] In 1917, as Lovecraft related to Kleiner, Lovecraft made an aborted attempt to enlist in the army. Though he passed the physical exam,[51] he told Kleiner that his mother "has threatened to go to any lengths, legal or otherwise, if I do not reveal all the ills which unfit me for the army".[52]

In the winter of 1918–1919, Susie, exhibiting symptoms of a "nervous breakdown" of some sort, went to live with her elder sister Lillian. It is unclear what Susie may have been suffering from. Neighbour and friend Clara Hess, interviewed in 1948, recalled instances of Susie describing "weird and fantastic creatures that rushed out from behind buildings and from corners at dark."[53] In the same account, Hess describes a time when they crossed paths in downtown Providence and Susie "was excited and apparently did not know where she was." Whatever the causes, in March 1919 they resulted in Susie being committed to Butler Hospital, like her husband before her.[54] Lovecraft's immediate reaction to Susie's commitment was visceral, writing to Kleiner that, "existence seems of little value," and that he wished "it might terminate".[55] Lovecraft periodically visited Susie and walked the large grounds with her.[56]

Late 1919 saw Lovecraft become more outgoing. After a period of isolation, he began joining friends in trips to writer gatherings; the first being a talk in Boston presented by Lord Dunsany, whom Lovecraft had recently discovered and idolized.[57] In early 1920, at an amateur writer convention, he met Frank Belknap Long, who would end up being Lovecraft's most influential and closest confidant for the rest of his life.[58] This period also proved to be the most prolific of Lovecraft's short-story career.[59] The influence of Dunsany is readily apparent in his 1919 output, later be to coined Lovecraft's Dream Cycle, with stories like "The White Ship", "The Doom That Came to Sarnath", and "The Statement of Randolph Carter". In early 1920 followed "The Cats of Ulthar" and "Celephaïs".[60]

It was later in 1920 that Lovecraft began publishing the earliest stories that fit into the Cthulhu Mythos. The Cthulhu Mythos, a term likely coined by August Derleth, encompasses Lovecraft's stories that share a commonality in the revelation of cosmic insignificance, initially realistic settings, and recurring entities and texts.[61] The poem "Nyarlathotep" and the short story "The Crawling Chaos", in collaboration with Winifred Virginia Jackson, were written in late 1920.[62] Following in early 1921 came "The Nameless City", the first story that falls definitively within the Cthulhu Mythos. In it is found one of Lovecraft's most enduring bits of writing, a couplet recited by his creation Abdul Alhazred, "That is not dead which can eternal lie; And with strange aeons even death may die."[63]

On May 24, 1921, Susie died in Butler Hospital, due to complications from a gall bladder surgery five days earlier. Lovecraft's initial reaction, expressed in a letter nine days after Susie's death, was that of an "extreme nervous shock" that crippled him physically and emotionally, again remarking that he found no reason he should continue living.[64] Despite Lovecraft's reaction, he continued to attend amateur journalist conventions. It was at one such convention in July that Lovecraft met Sonia Greene.[65]

Marriage and New York

Lovecraft's aunts disapproved of this relationship with Sonia. Lovecraft and Greene married on March 3, 1924, and relocated to her Brooklyn apartment at 793 Flatbush Avenue; she thought he needed to leave Providence to flourish and was willing to support him financially.[66] Greene, who had been married before, later said Lovecraft had performed satisfactorily as a lover, though she had to take the initiative in all aspects of the relationship. She attributed Lovecraft's passive nature to a stultifying upbringing by his mother.[67] Lovecraft's weight increased to 200 lb (91 kg) on his wife's home cooking.[68]

He was enthralled by New York, and, in what was informally dubbed the Kalem Club, he acquired a group of encouraging intellectual and literary friends who urged him to submit stories to Weird Tales; editor Edwin Baird accepted many otherworldly 'Dream Cycle' Lovecraft stories for the ailing publication, though they were heavily criticized by a section of the readership.[69] Established informally some years before Lovecraft arrived in New York, the core Kalem Club members were boys' adventure novelist Henry Everett McNeil, the lawyer and anarchist writer James Ferdinand Morton Jr., and the poet Reinhardt Kleiner.[70]

On New Year's Day of 1925, Sonia moved to Cleveland for a job opportunity, and Lovecraft left Flatbush for a small first-floor apartment on 169 Clinton Street "at the edge of Red Hook"—a location which came to discomfort him greatly.[71] Later that year, the Kalem Club's four regular attendees were joined by Lovecraft along with his protégé Frank Belknap Long, bookseller George Willard Kirk, and Samuel Loveman. Loveman was Jewish, but he and Lovecraft became close friends in spite of the latter's nativist attitudes.[72] By the 1930s, writer and publisher Herman Charles Koenig would be one of the last to be become involved with the Kalem Club.[73]

Not long after the marriage, Greene lost her business and her assets disappeared in a bank failure; she also became ill. Lovecraft made efforts to support his wife through regular jobs, but his lack of previous work experience meant he lacked proven marketable skills. After a few unsuccessful spells as a low-level clerk, his job-seeking became desultory. The publisher of Weird Tales attempted to put the loss-making magazine on a business footing and offered the job of editor to Lovecraft, who declined, citing his reluctance to relocate to Chicago; "think of the tragedy of such a move for an aged antiquarian," the 34-year-old writer declared. Baird was replaced with Farnsworth Wright, whose writing Lovecraft had criticized. Lovecraft's submissions were often rejected by Wright. (This may have been partially due to censorship guidelines imposed in the aftermath of a Weird Tales story that hinted at necrophilia, although after Lovecraft's death, Wright accepted many of the stories he had originally rejected.)[69]

Greene, moving to where the work was, relocated to Cincinnati, and then to Cleveland; her employment required constant travel. Added to the daunting reality of failure in a city with a large immigrant population, Lovecraft's single-room apartment at 169 Clinton Street in Brooklyn Heights, not far from the working-class waterfront neighborhood Red Hook, was burgled, leaving him with only the clothes he was wearing. In August 1925, he wrote "The Horror at Red Hook" and "He", in the latter of which the narrator says "My coming to New York had been a mistake; for whereas I had looked for poignant wonder and inspiration [...] I had found instead only a sense of horror and oppression which threatened to master, paralyze, and annihilate me." It was at around this time he wrote the outline for "The Call of Cthulhu", with its theme of the insignificance of all humanity. With a weekly allowance Greene sent, Lovecraft moved to a working-class area of Brooklyn Heights, where he subsisted in a tiny apartment. He had lost approximately 40 pounds (18 kg) of body weight by 1926, when he left for Providence.[74]

Return to Providence

Back in Providence, Lovecraft lived in a "spacious brown Victorian wooden house" at 10 Barnes Street until 1933.[75] The same address is given as the home of Dr. Willett in Lovecraft's The Case of Charles Dexter Ward. The period beginning after his return to Providence—the last decade of his life—was Lovecraft's most prolific; in that time he produced short stories, as well as his longest works of fiction: The Dream-Quest of Unknown Kadath, The Case of Charles Dexter Ward, and At the Mountains of Madness. He frequently revised work for other authors and did a large amount of ghostwriting, including The Mound, Winged Death, and The Diary of Alonzo Typer. Client Harry Houdini was laudatory, and attempted to help Lovecraft by introducing him to the head of a newspaper syndicate. Plans for a further project were ended by Houdini's death.[76]

Although he was able to combine his distinctive style (allusive and amorphous description by horrified though passive narrators) with the kind of stock content and action that the editor of Weird Tales wanted—Wright paid handsomely to snap up "The Dunwich Horror" which proved very popular with readers—Lovecraft increasingly produced work that brought him no remuneration. Affecting a calm indifference to the reception of his works, Lovecraft was in reality extremely sensitive to criticism and easily precipitated into withdrawal. He was known to give up trying to sell a story after it had been once rejected.[77]

Sometimes, as with The Shadow over Innsmouth (which included a rousing chase that supplied action) he wrote a story that might have been commercially viable but did not try to sell it. Lovecraft even ignored interested publishers. He failed to reply when one inquired about any novel Lovecraft might have ready: although he had completed such a work, The Case of Charles Dexter Ward, it was never typed up.[77] A few years after Lovecraft had moved to Providence, he and his wife Sonia Greene, having lived separately for so long, agreed to an amicable divorce. Greene moved to California in 1933 and remarried in 1936, unaware that Lovecraft, despite his assurances to the contrary, had never officially signed the final decree.[78]

Last years and death

Lovecraft was never able to provide for even basic expenses by selling stories and doing paid literary work for others. He lived frugally, subsisting on an inheritance that was nearly depleted by the time he died. He sometimes went without food to be able to pay the cost of mailing letters.[79] After leaving New York, he moved to an apartment at 10 Barnes Street near Brown University with his surviving aunt; a few years later, they moved to a slightly less expensive place at 65 Prospect Street. As a result of the Great Depression, he shifted towards socialism, decrying both his prior beliefs and the rising tide of fascism.[80] He supported Franklin D. Roosevelt, but he thought that the New Deal was not sufficiently leftist.[81]

In late 1936, he witnessed the publication of The Shadow over Innsmouth as a paperback book.[n 3] However, Lovecraft was displeased, as his book was riddled with errors. It sold slowly and only approximately 200 copies were bound. The remaining copies were destroyed after the publisher went out of business. By this point, Lovecraft's literary career had reached its end. Shortly after having written his last original short story, "The Haunter of the Dark", he stated that the hostile reception of At the Mountains of Madness had done "more than anything to end my effective fictional career."[82]

On June 11, Robert E. Howard committed suicide after being told that his mother would not awaken from her coma. His mother died shortly thereafter. This deeply affected Lovecraft, who consoled Howard's father. Almost immediately, Lovecraft wrote a brief memoir titled "In Memoriam: Robert Ervin Howard".[83] Meanwhile, Lovecraft's physical health was deteriorating. He was suffering from an affliction that he referred to as "grippe".[n 4][82]

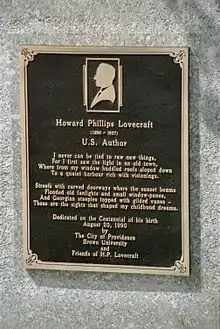

Due to his fear of doctors, Lovecraft was not examined until a mere month before his death. After seeing a doctor, he was diagnosed with terminal cancer of the small intestine. He remained hospitalized until he died. He lived in constant pain until his death on March 15, 1937, in Providence. In accordance with his lifelong scientific curiosity, he kept a diary of his illness until he was physically incapable of holding a pen.[85] Lovecraft was listed along with his parents on the Phillips family monument (41°51′14″N 71°22′52″W). In 1977, fans erected a headstone in Swan Point Cemetery on which they inscribed his name, the dates of his birth and death, and the phrase "I AM PROVIDENCE"—a line from one of his personal letters.[86]

Personal views

Politics

Lovecraft began his life as a Tory. This is likely the result of his conservative upbringing. His family supported the Republican Party for the entirety of his life. While it is unclear how consistently he voted, he voted for Herbert Hoover in the 1928 presidential election. Rhode Island as a whole remained politically conservative and Republican into the 1930s.[87] Lovecraft himself was an anglophile who supported the British monarchy. He opposed democracy and thought that America should be governed by an aristocracy.[88] His personal justification for his viewpoints was primarily based on tradition and aesthetics.[89]

As a result of the Great Depression, Lovecraft reexamined his political views. Initially, he thought that affluent people would take on the characteristics of his ideal aristocracy and solve America's problems. When this did not occur, he became a socialist. This shift was not brought on by a change in his living standards. Instead, it was caused by the increase in socialism's political capital during the 1930s. It was also caused by his observation that the Depression was harming American society. One of the main points of Lovecraft's socialism was its opposition to communism. He thought that a communist revolution would bring out the destruction of American civilization. Lovecraft thought that an intellectual aristocracy needed to be formed to preserve America.[90]

His ideal political system is outlined in his essay, "Some Repetitions on the Times." Lovecraft used this essay to echo the political proposals that had been made over the course of the last few decades. In this essay, he advocates governmental control of resource distribution, fewer working hours and a higher wage, and unemployment insurance and old age pensions. He also outlines the need for a oligarchy of intellectuals. In his view, power must be restricted to those who are sufficiently intelligent and educated.[91] He frequently used the term "fascism" to describe this form of government, but it bears little resemblance to that ideology.[92]

Lovecraft had varied views on the political figures of his day. He was an ardent supporter of Franklin D. Roosevelt. He saw that Roosevelt was trying to steer a middle course between the conservatives and the revolutionaries, which he approved of. While he thought that Roosevelt enact more progressive policies, he came to the conclusion that the New Deal was the only realistic option for reform. He thought that voting for his opponents on the political left would be a waste.[93] Internationally, like many Americans, he initially expressed support for Adolf Hitler. More specifically, he thought that Hitler would preserve German culture. However, he thought that Hitler's racial policies should be based on culture rather than descent. There is evidence that, at the end of his life, Lovecraft began to oppose Hitler. According to Harry K. Brobst, Lovecraft's downstairs neighbor went to Germany and witnessed Jews being beaten. Lovecraft and his aunt were angered by this. His discussions of Hitler drop off after this point.[94]

Atheism

Lovecraft was an atheist. His viewpoints on religion are outlined in his 1922 essay "A Confession of Unfaith." In this essay, he describes his shift away from the Protestantism of his parents to the atheism of his adulthood. Lovecraft was raised by a conservative Protestant family. He was introduced to the Bible and the mythos of Saint Nicholas when he was two. He passively accepted both of them. Over the course of the next few years, he was introduced to Grimms' Fairy Tales and One Thousand and One Nights, favoring the latter. In response, Lovecraft took on the identity of "Abdul Alhazred," a name he would later use for the author of the Necronomicon.[95] According to his account, his first moment of scepticism occurred before his fifth birthday, when he heard that Santa Claus is not real. He questioned if God is also a myth. In 1896, he was introduced to Greco-Roman myths and became "a genuine pagan."[96]

This came to an end in 1902, when Lovecraft was introduced to space. He later described this event ast the most poignant in his life. In response to this discovery, Lovecraft took to studying astronomy and described his observations in the local newspaper. Before his thirteenth birthday, he had become convinced of humanity's impermanence. By the time he was seventeen, he had read detailed writings that agreed with his worldview. Lovecraft ceased writing positively about progress, instead developing his later cosmic philosophy. Despite his interests in science, he had an aversion to realistic literature, so he became interested in fantastical fiction. This did not lessen his viewpoints. Lovecraft became pessimistic when he entered amateur journalism in 1914. The Great War seemed to confirm his viewpoints. He began to despise philosophical idealism. Lovecraft took to discussing and debating his pessimism with his peers, which allowed him to solidify his philosophy. His readings of Friedrich Nietzsche and H. L. Mencken, among other pessimistic writers, furthered this development. At the end of his essay, Lovecraft states that all he desired was oblivion. He was willing to cast aside any illusion that he may still have held.[97]

Race

Race is the most controversial aspect of Lovecraft's legacy, expressed in many disparaging remarks against the various non-Anglo-Saxon races and cultures in his work. As he grew older, his original racial worldview became a classism or elitism which regarded the superior race to include all those self-ennobled through high culture. From the start, Lovecraft did not hold all white people in uniform high regard, but rather esteemed English people and those of English descent.[98] In his 1912 poem "On the Creation of Niggers", Lovecraft describes black people not as human but as "beast[s] ... in semi-human figure, filled with vice." In his early published essays, private letters and personal utterances, he argued for a strong color line to preserve race and culture.[99] His arguments were justified using disparagement of various races in his journalism and letters,[82] and perhaps allegorically in his fiction concerning non-human races.[100]

Initially, Lovecraft showed sympathy to minorities who adopted Western culture, even to the extent of marrying a Jewish woman he viewed as "well assimilated."[101] By the 1930s, Lovecraft's views on ethnicity and race had moderated. He supported ethnicities' preserving their native cultures; for example, he thought that "a real friend of civilisation wishes merely to make the Germans more German, the French more French, the Spaniards more Spanish, & so on." This represented a shift from his previous support for cultural assimilation.[102] Lovecraft's racial attitudes were common in the society of his day, especially in the New England in which he grew up.[103]

Influences

His interest started from his childhood days when his grandfather, who preferred Gothic stories, would tell him stories of his own design. Lovecraft's childhood home on Angell Street had a large library. This library contained classical literature, scientific works, and early weird fiction. At the age of five, Lovecraft enjoyed reading One Thousand and One Nights, and was reading Hawthorne a year later. He was also influenced by the travel literature of John Mandeville and Marco Polo. This led to his discovery of gaps, which prevented Lovecraft from committing suicide during his adolescence. These travelogues may have also had an influence on how Lovecraft's later works describe their characters and locations. For example, there is a resemblance between the powers of the Tibetan enchanters in Polo's Travels and the powers unleashed on Sentinel Hill in "The Dunwich Horror".[104]

One of Lovecraft's most significant literary influences was Edgar Allan Poe, whom he described as his "God of Fiction."[105] Like Lovecraft, Poe was out of step with the prevailing literary trends of his era. Both authors created distinctive, singular worlds of fantasy and employed archaisms in their writings. This influence can be found in such works as his novella The Shadow over Innsmouth[106] where Lovecraft references Poe's story "The Imp of the Perverse" by name in Chapter 3, and in his poem "Nemesis", where the "... ghoul-guarded gateways of slumber"[107] suggest the "... ghoul-haunted woodland of Weir"[108] found in Poe's "Ulalume". A direct quote from the poem and a reference to Poe's only novel The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket is alluded to in Lovecraft's magnum opus At the Mountains of Madness.[109] Both authors shared many biographical similarities as well, such as the loss of their fathers at young ages and an early interest in poetry.[110]

He was influenced by Arthur Machen's[111] carefully constructed tales concerning the survival of ancient evil into modern times in an otherwise realistic world and his beliefs in hidden mysteries which lay behind reality. Lovecraft was also influenced by authors such as Oswald Spengler and Robert W. Chambers. Chambers was the writer of The King in Yellow, of whom Lovecraft wrote in a letter to Clark Ashton Smith: "Chambers is like Rupert Hughes and a few other fallen Titans – equipped with the right brains and education but wholly out of the habit of using them." Lovecraft's discovery of the stories of Lord Dunsany,[112] with their pantheon of mighty gods existing in dreamlike outer realms, moved his writing in a new direction, resulting in a series of imitative fantasies in a Dreamlands setting.[113]

Lovecraft also cited Algernon Blackwood as an influence, quoting The Centaur in the head paragraph of "The Call of Cthulhu". He declared Blackwood's story The Willows to be the single best piece of weird fiction ever written.[114] Another inspiration came from a completely different source: scientific progress in biology, astronomy,[115] geology, and physics.[116] His study of science contributed to Lovecraft's view of the human race as insignificant, powerless, and doomed in a materialistic and mechanistic universe.[117] Lovecraft was a keen amateur astronomer from his youth, often visiting the Ladd Observatory in Providence, and penning numerous astronomical articles for his personal journal and local newspapers.[118]

Lovecraft's materialist views led him to espouse his philosophical views through his fiction; these philosophical views came to be called cosmicism. Cosmicism took on a more pessimistic tone with his creation of what is now known as the Cthulhu Mythos; a fictional universe that contains alien deities and horrors. The term "Cthulhu Mythos" was likely coined by Lovecraft's correspondent and protégé, August Derleth, after Lovecraft's death.[1] In his letters, Lovecraft jokingly called his fictional mythology "Yog-Sothothery."[119]

Dreams had a major role in Lovecraft's literary career.[120] In 1991, as a result of his rising place in American literature, it was popularly thought that Lovecraft extensively transcribed his dreams when writing fiction. However, the majority of his stories are not transcribed dreams. Instead, many of them are directly influenced by dreams and dreamlike phenomena. In his letters, Lovecraft frequently compared his characters to dreamers. They are described as being as helpless as a real dreamer who is experiencing a nightmare. His stories also have dreamlike qualities. The Randolph Carter stories deconstruct the division between dreams and reality. The dreamlands in The Dream-Quest of Unknown Kadath are a shared dreamworld that can be accessed by a sensitive dreamer. Meanwhile, in "The Silver Key", Lovecraft mentions the concept of "inward dreams," which implies the existence of outward dreams. Burleson compares this deconstruction to Carl Jung's argument that dreams are the source of archetypal myths. Lovecraft's way of writing fiction required both a level of realism and dreamlike elements. Citing Jung, Burleson argues that a writer may create realism by being inspired by dreams.[121]

Lovecraft's use of British English owes much to his father's influence. He described his father as having been so anglophilic that he was commonly presumed to be an Englishman. According to Lovecraft, his father had been constantly warned to avoid using Americanized words and phrases. This influence stretched beyond Lovecraft's use of language. His father's Anglophilia had also caused Lovecraft to have a deep affection for British culture and the British Empire.[122]

Themes

Several themes recur in Lovecraft's stories:

— H. P. Lovecraft, in note to the editor of Weird Tales, on resubmission of "The Call of Cthulhu"[123]

Forbidden knowledge

Forbidden, dark, esoterically veiled knowledge is a central theme in many of Lovecraft's works. The awe and dread described by the characters in Lovecraft's weird fiction baffle them; they are stunned as their minds struggle to comprehend the alien things before them. They can only describe their own sensations in the presence of great horrors, such as the way the beings smell or what horrible sounds they make. The scientists of Lovecraft's stories usual stumble while trying to describe the terrible shape of the beings - essentially failing at describing what they actually are.[124]

Many of his characters are driven by curiosity or scientific endeavor, and in many of his stories the knowledge they uncover proves Promethean in nature, either filling the seeker with regret for what they have learned, destroying them psychologically, or completely destroying the person who holds the knowledge. [125] Some critics argue that this theme is a reflection of Lovecraft's contempt of the world around him, causing him to search inwardly for knowledge and inspiration.[126]

Non-human influences on humanity

The beings of Lovecraft's mythos often have human servants; Cthulhu, for instance, is worshipped under various names by cults among both the Greenlandic Inuit and voodoo circles of Louisiana, and in many other parts of the world.

These worshippers served a useful narrative purpose for Lovecraft. Many beings of the Mythos were too powerful to be defeated by human opponents, and so horrific that direct knowledge of them meant insanity for the victim. When dealing with such beings, Lovecraft needed a way to provide exposition and build tension without bringing the story to a premature end. Human followers gave him a way to reveal information about their "gods" in a diluted form, and also made it possible for his protagonists to win paltry victories. Lovecraft, like his contemporaries, envisioned "savages" as closer to supernatural knowledge unknown to civilized man.

Fate

Often in Lovecraft's works, the protagonist is not in control of his own actions or finds it impossible to change course. Many of his characters would be free from danger if they simply managed to run away; however, this possibility either never arises or is somehow curtailed by some outside force, such as in "The Colour Out of Space" and "The Dreams in the Witch House". Often his characters are subject to a compulsive influence from powerful malevolent or indifferent beings. As with the inevitability of one's ancestry, eventually even running away, or death itself, provides no safety (The Thing on the Doorstep, "The Outsider", The Case of Charles Dexter Ward). In some cases, this doom is manifest in the entirety of humanity, and no escape is possible (The Shadow Out of Time).

Another recurring theme in Lovecraft's stories is the idea that descendants in a bloodline can never escape the stain of crimes committed by their forebears, at least if the crimes are atrocious enough. Descendants may be very far removed, both in place and in time (and, indeed, in culpability), from the act itself, and yet, they may be haunted by the revenant past, e.g. "The Rats in the Walls", "The Lurking Fear", "Facts Concerning the Late Arthur Jermyn and His Family", "The Alchemist", The Shadow over Innsmouth, "The Doom That Came to Sarnath" and The Case of Charles Dexter Ward.

Civilization under threat

Lovecraft was familiar with the work of the German conservative-revolutionary theorist Oswald Spengler, whose pessimistic thesis of the decadence of the modern West formed a crucial element in Lovecraft's overall anti-modern worldview. Spenglerian imagery of cyclical decay is present in particular in At the Mountains of Madness. S. T. Joshi, in H. P. Lovecraft: The Decline of the West, places Spengler at the center of his discussion of Lovecraft's political and philosophical ideas.[127]

Lovecraft wrote to Clark Ashton Smith in 1927: "It is my belief, and was so long before Spengler put his seal of scholarly proof on it, that our mechanical and industrial age is one of frank decadence."[128] Lovecraft was also acquainted with the writings of another German philosopher of decadence: Friedrich Nietzsche.[129]

Lovecraft frequently dealt with the idea of civilization struggling against dark, primitive barbarism. In some stories this struggle is at an individual level; many of his protagonists are cultured, highly educated men who are gradually corrupted by some obscure and feared influence. In such stories, the curse is often a hereditary one, either because of interbreeding with non-humans (e.g., Facts Concerning the Late Arthur Jermyn and His Family (1920), The Shadow over Innsmouth (1931)) or through direct magical influence (The Case of Charles Dexter Ward).

In other tales, an entire society is threatened by barbarism. Sometimes the barbarism comes as an external threat, with a civilized race destroyed in war (e.g. "Polaris"). Sometimes, an isolated pocket of humanity falls into decadence and atavism of its own accord (e.g. "The Lurking Fear"). But most often, such stories involve a civilized culture being gradually undermined by a malevolent underclass influenced by inhuman forces.

Risks of a scientific era

At the turn of the 20th century, humanity's increased reliance upon science was both opening new worlds and solidifying understanding of ours. Lovecraft portrays this potential for a growing gap of man's understanding of the universe as a potential for horror, most notably in "The Colour Out of Space", where the inability of science to comprehend a contaminated meteorite leads to horror.[130]

In a letter to James F. Morton in 1923, Lovecraft specifically pointed to Albert Einstein's theory on relativity as throwing the world into chaos and making the cosmos a jest; in a letter to Woodburn Harris in 1929, he speculated that technological comforts risk the collapse of science. Indeed, at a time when men viewed science as limitless and powerful, Lovecraft imagined alternative potential and fearful outcomes. In "The Call of Cthulhu", Lovecraft's characters encounter architecture which is "abnormal, non-Euclidean, and loathsomely redolent of spheres and dimensions apart from ours."[131] Non-Euclidean geometry is the mathematical language and background of Einstein's general theory of relativity, and Lovecraft references it repeatedly in exploring alien archaeology.[132]

Religion and superstition

Lovecraft's works are ruled by several distinct pantheons of deities (actually aliens worshiped as gods by humans) who are either indifferent or actively hostile to humanity. Lovecraft's personal philosophy has been termed "cosmic indifference" and this is expressed in his fiction.[133] Several of Lovecraft's stories of the Old Ones (alien beings of the Cthulhu Mythos) propose alternate mythic human origins in contrast to those found in the creation stories of existing religions, expanding on a natural world view. For instance, in Lovecraft's At the Mountains of Madness, it is proposed that humankind was actually created as a slave race by the Old Ones, and that life on Earth as we know it evolved from scientific experiments abandoned by the Elder Things.[134]

Protagonist characters in Lovecraft are usually educated men, citing scientific and rational evidence to support their non-faith. "Herbert West–Reanimator" reflects on the atheism common in academic circles. In "The Silver Key", the character Randolph Carter loses the ability to dream and seeks solace in religion, specifically Congregationalism, but does not find it and ultimately loses faith.

Lovecraft himself adopted the stance of atheism early in life. In 1932, he wrote in a letter to Robert E. Howard:

All I say is that I think it is damned unlikely that anything like a central cosmic will, a spirit world, or an eternal survival of personality exist. They are the most preposterous and unjustified of all the guesses which can be made about the universe, and I am not enough of a hairsplitter to pretend that I don't regard them as arrant and negligible moonshine. In theory, I am an agnostic, but pending the appearance of radical evidence I must be classed, practically and provisionally, as an atheist."[135]

In 1926, famed magician and escapist Harry Houdini asked Lovecraft to ghostwrite a treatise exploring the topic of superstition. Houdini's unexpected death later that year halted the project, but The Cancer of Superstition was partially completed by Lovecraft along with collaborator C. M. Eddy Jr. A previously unknown manuscript of the work was discovered in 2016 in a collection owned by a magic shop. The book states "all superstitious beliefs are relics of a common 'prehistoric ignorance' in humans," and goes on to explore various superstitious beliefs in different cultures and times."[136]

Lovecraft Country

Lovecraft drew extensively from his native New England for settings in his fiction. Numerous historical cities and towns are mentioned, and several fictionalised versions of them make frequent appearances in his stories.[n 5] These municipalities are located in the western half of a fictionalized Massachusetts. The exact locations of these municipalities were subject to change with Lovecraft's shifting literary needs. Starting with areas that he thought were evocative, Lovecraft redefined and exaggerated them under fictional names. For example, Lovecraft renamed the town of Oakham to Arkham and expanded it to include a nearby landmark.[137]

Critical reception

Within the genre

By 1957, Floyd C. Gale of Galaxy Science Fiction said that "like R. E. Howard, Lovecraft seemingly goes on forever; the two decades since their death are as nothing. In any event, they appear more prolific than ever. What with de Camp, Nyberg and Derleth avidly rooting out every scrap of their writings and expanding them into novels, there may never be an end to their posthumous careers."[138] According to Joyce Carol Oates, Lovecraft (and Edgar Allan Poe in the 19th century) has exerted "an incalculable influence on succeeding generations of writers of horror fiction."[139] Horror, fantasy, and science fiction author Stephen King called Lovecraft "the twentieth century's greatest practitioner of the classic horror tale."[140] King has made it clear in his semi-autobiographical non-fiction book Danse Macabre that Lovecraft was responsible for his own fascination with horror and the macabre and was the largest influence on his writing.[141]

Literary

Early efforts to revise an established literary view of Lovecraft as an author of 'pulp' were resisted by some eminent critics; in 1945, Edmund Wilson sneered: "the only real horror in most of these fictions is the horror of bad taste and bad art." However, Wilson praised Lovecraft's ability to write about his chosen field; he described him as having written about it "with much intelligence."[142] According to L. Sprague de Camp, Wilson later improved his opinion of Lovecraft, citing a report of David Chavchavadze that Wilson had included a Lovecraftian reference in Little Blue Light: A Play in Three Acts. After Chavchavadze met with him to discuss this, Wilson revealed that he had been reading a copy of Lovecraft's correspondence.[n 6][143] Mystery and Adventure columnist Will Cuppy of the New York Herald Tribune recommended to readers a volume of Lovecraft's stories, asserting that "the literature of horror and macabre fantasy belongs with mystery in its broader sense."[144]

Galaxy Science Fiction reviewer Floyd C. Gale said that "Lovecraft at his best could build a mood of horror unsurpassed; at his worst, he was laughable."[138] In 1962, Colin Wilson, in his survey of anti-realist trends in fiction The Strength to Dream, cited Lovecraft as one of the pioneers of the "assault on rationality" and included him with M. R. James, H. G. Wells, Aldous Huxley, J. R. R. Tolkien and others as one of the builders of mythicised realities contending against the failing project of literary realism.[145] Subsequently, Lovecraft began to acquire the status of a cult writer in the counterculture of the 1960s, and reprints of his work proliferated.[146]

Michael Dirda, a reviewer for The Times Literary Supplement, has described Lovecraft as being a "visionary" who is "rightly regarded as second only to Edgar Allan Poe in the annals of American supernatural literature." According to him, Lovecraft's works prove that mankind cannot bear the weight of reality, as the true nature of reality cannot be understood by either science or history. In addition, Dirda praises Lovecraft's ability to create an uncanny atmosphere. This atmosphere is created through the feeling of wrongness that pervades the objects, places, and people in Lovecraft's works. He also comments favorably on Lovecraft's correspondence, and compares him to Horace Walpole. Particular attention is given to his correspondence with August Derleth and Robert E. Howard. The Derleth letters are called "delightful," while the Howard letters are described as being an ideological debate. Overall, Dirda believes that Lovecraft's letters are equal to, or better than, his fictional output.[147]

Los Angeles Review of Books reviewer Nick Mamatas stated that Lovecraft was a particularly difficult author, rather than a bad one. He described Lovecraft as being "perfectly capable" in the fields of story logic, pacing, innovation, and generating quotable phrases. However, Lovecraft's difficulty made him ill-suited to the pulps; he was unable to compete with the popular recurring protagonists and damsel-in-distress stories. Furthermore, he compared a paragraph from The Shadow Out of Time to a paragraph from the introduction to The Economic Consequences of the Peace. In Mamatas' view, Lovecraft's quality is obscured by his difficulty, and his skill is what has allowed his following to outlive the followings of other prominent authors, such as Seabury Quinn and Kenneth Patchen.[148]

In 2005, the Library of America published a volume of Lovecraft's works. This volume was reviewed by many publications, including The New York Times Book Review and The Wall Street Journal, and sold 25,000 copies within a month of release. The overall critical reception of the volume was mixed.[149] Several scholars, including S. T. Joshi and Alison Sperling, have said that this confirms H. P. Lovecraft's place in the western canon.[150]

The editors of The Age of Lovecraft, Carl H. Sederholm and Jeffrey Andrew Weinstock, attributed the rise of mainstream popular and academic interest in Lovecraft to this volume, along with the Penguin Classics volumes and the Modern Library edition of At the Mountains of Madness. These volumes led to a proliferation of other volumes containing Lovecraft's works. According to the two authors, these volumes are part of a trend in Lovecraft's popular and academic reception: increased attention by one audience causes the other to also become more interested. Lovecraft's success is, in part, the result of his success.[151]

Lovecraft's style has often been subject to criticism,[111] but scholars such as S. T. Joshi have shown that Lovecraft consciously utilized a variety of literary devices to form a unique style of his own – these include prose-poetic rhythm, stream of consciousness, alliteration, and conscious archaism (largely in his pre-1921 works).[152]

Philosophical

Philosopher Graham Harman, seeing Lovecraft as expressing a unique—though implicit—antireductionist ontology, writes: "No other writer is so perplexed by the gap between objects and the power of language to describe them, or between objects and the qualities they possess."[153] Speculative realists, Mark Fisher and other contemporary philosophers, took Lovecraft seriously, mainly because Lovecraft's weird fictional world, had nothing to do with the Gothic's insistence on the supernatural, but presented another undeniable but incomprehensible reality. According to scholar S. T. Joshi: "There is never an entity in Lovecraft that is not in some fashion material."[154] Philosopher Eugene Thacker echoes this in his "Horror of Philosophy" series of books, finding in Lovecraft's ideas a "cold rationalism" or "cosmic pessimism" that highlights the limitations of anthropocentric thinking.[155] Thacker at one point characterizes this as a tension between "I can't believe what I see" and "I can't see what I believe."[156]

2010s and 2020s reception

Several media outlets published articles discussing Lovecraft's legacy as a horror fiction writer, with many outlets in the 2010s discussing and criticizing Lovecraft's racism and homophobia.[157] Public Books connected Lovecraft's upbringing in Providence to the "racism, homophobia, misogyny, and general parochialism" found in his personal beliefs and work, calling it "unquestionably rooted in places, aesthetics, and an idiosyncratic sense of local culture."[158] The African-American fantasy writer N. K. Jemisin considers Lovecraft's racial attitudes essential to his literary world: "his biases were the basis of his horror. ... He does some incredible imagery, it's powerful work, but it's frightening ... because it's a way to look into the mind of a true bigot, and realize just how alien their thinking is, just how disturbing their ability to dehumanize their fellow human beings is".[159]

The first World Fantasy Awards were held in Providence in 1975. The theme was "The Lovecraft Circle." Until 2015, winners were presented with an elongated bust of Lovecraft that was designed by cartoonist Gahan Wilson, nicknamed the "Howard."[157] In November 2015 it was announced that the World Fantasy Award trophy would no longer be modeled on H. P. Lovecraft.[160] After the World Fantasy Award dropped their connection to Lovecraft, The Atlantic commented that "In the end, Lovecraft still wins—people who've never read a page of his work will still know who Cthulhu is for years to come, and his legacy lives on in the work of Stephen King, Guillermo del Toro, and Neil Gaiman."[157]

In 2020, Lovecraft was awarded the 1945 Retro-Hugo Award for Best Series for the Cthulhu Mythos.[161]

Legacy

Lovecraft was relatively unknown during his lifetime.[162] While his stories appeared in prominent pulp magazines such as Weird Tales (eliciting letters of outrage as often as praise from regular readers), not many people knew his name. He did, however, correspond regularly with other contemporary writers such as Clark Ashton Smith and August Derleth,[163] who became his good friends, even though he never met them in person. This group became known as the "Lovecraft Circle," since their writing freely borrowed Lovecraft's motifs, with his encouragement: the mysterious books with disturbing names such as the Necronomicon, the pantheon of ancient alien entities such as Cthulhu and Azathoth, and eldritch places such as the ill-omened New England town of Arkham and its Miskatonic University.

After Lovecraft's death, the Lovecraft Circle carried on. August Derleth in particular added to and expanded on Lovecraft's vision, not without controversy. While Lovecraft considered his pantheon of alien gods a mere plot device, Derleth created an entire cosmology, complete with a war between the good Elder Gods and the evil Outer Gods, such as Cthulhu and his ilk. The forces of good were supposed to have won, locking Cthulhu and others beneath the earth, the ocean, and elsewhere. Derleth's Cthulhu Mythos stories went on to associate different gods with the traditional four elements of fire, air, earth and water — an artificial constraint which required rationalizations on Derleth's part as Lovecraft himself never envisioned such a scheme.[1]

Lovecraft's writing, particularly the so-called Cthulhu Mythos, has influenced fiction authors including modern horror and fantasy writers. Stephen King,[140] Ramsey Campbell,[164] Alan Moore,[165] Junji Ito,[166] Thomas Ligotti,[167] Caitlín R. Kiernan,[168] William S. Burroughs,[169] and Neil Gaiman,[170] have cited Lovecraft as one of their primary influences. Beyond direct adaptation, Lovecraft and his stories have had a profound impact on popular culture. Some influence was direct, as he was a friend, inspiration, and correspondent to many of his contemporaries, such as August Derleth, Robert E. Howard, Robert Bloch and Fritz Leiber.[171]

Many later figures were influenced by Lovecraft's works, including author and artist Clive Barker,[172] prolific horror writer Stephen King,[164] comics writers Alan Moore, Neil Gaiman[173] and Mike Mignola,[174] English author Colin Wilson, film directors John Carpenter,[162] Stuart Gordon, Guillermo del Toro,[173] and artist H. R. Giger.[175]

Japan has also been significantly inspired and terrified by Lovecraft's creations and thus even entered the manga and anime media. Chiaki J. Konaka is an acknowledged disciple and has participated in Cthulhu Mythos, expanding several Japanese versions, and is credited for spreading the influence of Lovecraft among the anime base.[176]

Argentine writer Jorge Luis Borges wrote his short story "There Are More Things" in memory of Lovecraft. Contemporary French writer Michel Houellebecq wrote a literary biography, H. P. Lovecraft: Against the World, Against Life. Prolific American writer Joyce Carol Oates wrote an introduction for a collection of Lovecraft stories. The Library of America published a volume of Lovecraft's work in 2005, a reversal of the traditional judgment that there "has been nothing so far from the accepted canon as Lovecraft."[177] French philosophers Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari refer to Lovecraft in A Thousand Plateaus, calling the short story "Through the Gates of the Silver Key" one of his masterpieces.[178]

Groups of enthusiasts annually observe the anniversaries of Lovecraft's death at Ladd Observatory and of his birth at his grave site. In July 2013, the Providence City Council designated "H. P. Lovecraft Memorial Square" and installed a commemorative sign at the intersection of Angell and Prospect streets, near the author's former residences.[179] In 2016, Lovecraft was inducted into the Museum of Pop Culture's Science Fiction and Fantasy Hall of Fame.[180]

Music

Lovecraft's fictional Mythos has influenced a number of musicians, especially in rock music. The psychedelic rock band H. P. Lovecraft (who shortened their name to Lovecraft and then Love Craft in the 1970s) released the albums H. P. Lovecraft and H. P. Lovecraft II in 1967 and 1968 respectively; their songs included "The White Ship" and "At the Mountains of Madness", both titled after Lovecraft stories. Bill Traut and George Badonsky, who set up Dunwich Records, were fans of the author and gained August Derleth's permission to use Lovecraft's name for the band.[181]

Metallica recorded a song inspired by "The Call of Cthulhu", an instrumental titled The Call of Ktulu, a song based on The Shadow over Innsmouth titled The Thing That Should Not Be and another based on Frank Belknap Long's Hounds of Tindalos titled All Nightmare Long. Later, they released the song Dream No More, which mentions the awakening of Cthulhu.[182] Technical death metal outfit Revocation frequently write songs based on Lovecraft's stories and often use him as inspiration in their original works.[183] The Darkest of the Hillside Thickets have referenced Lovecraft's works in songs such as "Shoggoths Away" and albums such as Cthulhu Strikes Back. According to Gary Hill's The Strange Sounds of Cthulhu, their band's raison d'être is to reference Lovecraft's tales. Their name is derived from a line in "The Tomb".[184]

Games

Lovecraft has also influenced gaming, despite having hated games during his lifetime.[185] Chaosium's tabletop role-playing game Call of Cthulhu, released in 1981 and currently in its seventh major edition, was one of the first games to draw heavily from Lovecraft. Novel to the game was the Lovecraft-inspired insanity mechanic, which allowed for player characters to go insane from contact with cosmic horrors. This mechanic would go on to make appearance in subsequent table top and video games.[186]

1987 saw the release of one of the first Lovecraftian board games, Arkham Horror, which sold extremely well, and since 2004 is still in print from Fantasy Flight Games. Though few subsequent Lovecraftian board games were released annually from 1987 to 2014, the years after 2014 saw a surge in the number of Lovecraftian board games, possibly because of the entry of Lovecraft's work into the public domain combined with a revival of interest in board games.[187]

Few video games are direct adaptations of Lovecraft's works, but many video games have been inspired or heavily influenced by Lovecraft.[186] The massively-multiplayer online game World of Warcraft by Blizzard Entertainment has continually revealed more of the origin story of the game's playable world to the players, most of which very closely mirrors Lovecraft's work or Derleth's expansion onto the author's original content.[188] Horror games especially can incorporate Cthulthean terrors, despite the conflict between "act-and-prevail" nature of video games and the cosmic hopelessness of Lovecraftian horror. Besides employing Cthulthean antagonists, games that invoke Lovecraftian horror have used mechanics such as insanity effects, or even fourth wall breaking effects that suggest to players that something has gone wrong with their game consoles.[189]

Religion and occultism

Several contemporary religions have drawn influence from the works of Lovecraft. The Satanic Rituals, written either by Anton LaVey or Michael A. Aquino, includes an essay which claims that the works of Lovecraft carry a partial truth, used in the same symbolic manner as Satan. Kenneth Grant of the Typhonian Order incorporated Lovecraft's Mythos into his ritual and occult system, but in a more direct and literal sense than the Church of Satan. However, the Typhonian Order does not consider the entities to be directly existent, but rather a symbol through which people may interact with something inhuman.[190]

There have been several books that have claimed to be an authentic edition of Lovecraft's Necronomicon.[191] The Simon Necronomicon is one such example. It was written by an unknown figure who identified themselves as "Simon." Peter Levenda, an occult author who has written about the Necronomicon, claims that he and "Simon" came across a hidden Greek translation of the grimoire while looking through a collection of antiquities at a New York bookstore during the 1960s or 1970s.[192] This book was claimed to have born the seal of the Necronomicon. Levenda went on to claim that Lovecraft had access to this purported scroll.[193] A textual analysis has determined that the contents of this book were derived from multiple documents that discuss Mesopotamian myth and magic. The finding of a magical text by monks is also a common theme in the history of grimoires.[194] It has been suggested that Lavenda is the true author of the Simon Necronomicon.[195]

Editions and collections of works

For most of the 20th century, the definitive editions (specifically At the Mountains of Madness and Other Novels, Dagon and Other Macabre Tales, The Dunwich Horror and Others, and The Horror in the Museum and Other Revisions) of his prose fiction were published by Arkham House, a publisher originally started with the intent of publishing the work of Lovecraft, but which has since published a considerable amount of other literature as well.

Penguin Classics has at present issued three volumes of Lovecraft's works: The Call of Cthulhu and Other Weird Stories, The Thing on the Doorstep and Other Weird Stories, and most recently The Dreams in the Witch House and Other Weird Stories. They collect the standard texts as edited by S. T. Joshi, most of which were available in the Arkham House editions, with the exception of the restored text of The Shadow Out of Time from The Dreams in the Witch House, which had been previously released by small-press publisher Hippocampus Press. In 2005 the prestigious Library of America canonized Lovecraft with a volume of his stories edited by Peter Straub, and Random House's Modern Library line have issued the "definitive edition" of Lovecraft's At the Mountains of Madness (also including Supernatural Horror in Literature).

In 2014, Liveright Publishing Corp./W. W. Norton published The New Annotated H. P. Lovecraft, edited by Leslie S. Klinger, containing 22 of Lovecraft's tales, with an introduction by Alan Moore; in September 2019, the second volume of Klinger's annotations, The New Annotated H. P. Lovecraft: Beyond Arkham, containing another 25 of Lovecraft's tales, was published, with an introduction by Victor LaValle.

Lovecraft's poetry is collected in The Ancient Track: The Complete Poetical Works of H. P. Lovecraft (Night Shade Books, 2001), while much of his juvenilia, various essays on philosophical, political and literary topics, antiquarian travelogues, and other things, can be found in Miscellaneous Writings (Arkham House, 1989). Lovecraft's essay Supernatural Horror in Literature, first published in 1927, is a historical survey of horror literature available with endnotes as The Annotated Supernatural Horror in Literature.

Correspondence

Although Lovecraft is known mostly for his works of weird fiction, the bulk of his writing consists of voluminous letters about a variety of topics, from weird fiction and art criticism to politics and history. Lovecraft's biographer L. Sprague de Camp estimates that Lovecraft wrote 100,000 letters in his lifetime, a fifth of which are believed to survive.[196]

Lovecraft was not an active letter-writer in youth. In 1931 he admitted: "In youth I scarcely did any letter-writing — thanking anybody for a present was so much of an ordeal that I would rather have written a two hundred fifty-line pastoral or a twenty-page treatise on the rings of Saturn." (SL 3.369–70). The initial interest in letters stemmed from his correspondence with his cousin Phillips Gamwell and his involvement in the amateur journalism movement. Lovecraft's later correspondence was primarily to fellow weird fiction writers, rather than to the amateur journalist friends of his earlier years. He sometimes dated his letters 200 years before the current date, which would have put the writing back in US colonial times, before the American Revolution (a war that offended his Anglophilia). He explained that he thought that the 18th and 20th centuries were the "best," the former being a period of noble grace, and the latter a century of science.

Lovecraft clearly states that his contact to numerous different people through letter-writing was one of the main factors in broadening his view of the world: "I found myself opened up to dozens of points of view which would otherwise never have occurred to me. My understanding and sympathies were enlarged, and many of my social, political, and economic views were modified as a consequence of increased knowledge."[197]

There are five publishing houses that have released letters from Lovecraft, most prominently Arkham House with its five-volume edition Selected Letters (these volumes severely abridge the letters they contain). Other publishers are Hippocampus Press (Letters to Alfred Galpin et al.), Night Shade Books (Mysteries of Time and Spirit: The Letters of H. P. Lovecraft and Donald Wandrei et al..), Necronomicon Press (Letters to Samuel Loveman and Vincent Starrett et al.), and University of Tampa Press (O Fortunate Floridian: H. P. Lovecraft's Letters to R. H. Barlow). S. T. Joshi is supervising an ongoing series of volumes collecting Lovecraft's unabridged letters to particular correspondents.

Copyright and other legal issues

Despite several claims to the contrary, there is currently no evidence that any company or individual owns the copyright to any of Lovecraft's work, and it is generally accepted that it has passed into the public domain.[198] The European Union Copyright Duration Directive of 1993 extended the copyrights to 70 years after the author's death. All of Lovecraft's works published during his lifetime became public domain in all 27 European Union countries on January 1, 2008. In those Berne Convention countries that have implemented only the minimum copyright period, copyright expires 50 years after the author's death. Regarding the United States, all works published before 1926 are public domain. Works Lovecraft published during his lifetime between 1926 and 1937 will indisputably be out of copyright as they enter the public domain annually between 2022 and 2033 (pre-1978 works do not use the life+70 rule in the USA).[199]

Lovecraft had specified that the young R. H. Barlow would serve as executor of his literary estate,[200] but these instructions were not incorporated into the will. Nevertheless, his surviving aunt carried out his expressed wishes, and Barlow was given charge of the massive and complex literary estate upon Lovecraft's death. Barlow deposited the bulk of the papers, including the voluminous correspondence, with the John Hay Library, and attempted to organize and maintain Lovecraft's other writing. August Derleth, an older and more established writer than Barlow, vied for control of the literary estate. Barlow committed suicide in 1951.[201]

Lovecraft protégés and part owners of Arkham House, August Derleth and Donald Wandrei, often claimed copyrights over Lovecraft's works. On October 9, 1947, Derleth purchased all rights to Weird Tales. However, since April 1926 at the latest, Lovecraft had reserved to himself all second printing rights to stories published in Weird Tales. Weird Tales may only have owned the rights to at most six of Lovecraft's tales. Again, even if Derleth did obtain the copyrights to Lovecraft's tales, there is no evidence that the copyrights were renewed. Following Derleth's death in 1971, his attorney proclaimed that all of Lovecraft's literary material was part of the Derleth estate and that it would be "protected to the fullest extent possible."[198]

S. T. Joshi concludes in his biography of Lovecraft that Derleth's claims are "almost certainly fictitious" and that most of Lovecraft's works published in the amateur press are most likely now in the public domain. The copyright for Lovecraft's works would have been inherited by the only surviving heir named in his 1912 will, his aunt Annie Gamwell.[200] When Gamwell died in 1941, the copyrights passed to her remaining descendants, Ethel Phillips Morrish and Edna Lewis, who then signed a document, sometimes referred to as the Morrish-Lewis gift, permitting Arkham House to republish Lovecraft's works while retaining the copyrights for themselves. Searches of the Library of Congress have failed to find any evidence that these copyrights were renewed after the 28-year period, making it likely that these works are now in the public domain.[198] Regardless of the legal disagreements surrounding Lovecraft's works, Lovecraft himself was extremely generous with his own works and encouraged others to borrow ideas from his stories and build on them, particularly with regard to his Cthulhu Mythos. He encouraged other writers to reference his creations, such as the Necronomicon, Cthulhu and Yog-Sothoth.[202]

Bibliography

See also

- Category:H. P. Lovecraft scholars

Notes

- Lovecraft did not coin the term "Cthulhu Mythos." Instead, this term was probably coined by August Derleth.[1]

- This is according to L. Sprague de Camp and S. T. Joshi's estimates.[2]

- This is the only one of Lovecraft's stories that was published as a book during his lifetime.[82]

- "Grippe" is an archaic term for influenza.[84]

- These fictional locations include Arkham, Dunwich, Innsmouth, and Kingsport.[137]

- L. Sprague de Camp also stated that the two men began calling each other "Monstro." This is a direct reference to the nicknames that Lovecraft gave to some of his correspondents.[143]

References

- Tierney 2012, p. 52.

- Joshi 1996, p. 236.

- Joshi 2010a, p. 16.

- Joshi 2010a, p. 8.

- Joshi 2010a, p. 26.

- Joshi 2010a, p. 22.

- Joshi 2010a, p. 28.

- de Camp 1975, p. 2.

- Joshi 2010a, pp. 33, 36.

- Joshi 2010a, p. 34.

- Joshi 2010a, p. 38.

- Joshi 2010a, p. 42.

- Joshi 2010a, p. 60.

- Joshi 2010a, p. 84.

- Joshi 2010a, p. 90.

- Joshi 2010a, p. 97.

- Joshi 2010a, p. 96.

- Joshi 2010a, p. 98.

- Joshi 2010a, p. 99.

- Joshi 2010a, p. 102.

- Joshi 2010a, p. 116.

- Joshi 2010a, p. 126.

- de Camp 1975, p. 27.

- Joshi 2010a, p. 127.

- Joshi 2010a, p. 128.

- de Camp 1975, p. 66.

- de Camp 1975, p. 64.

- Bonner 2015, pp. 52–53.

- Joshi & Schultz 2001, p. 154.

- Joshi 2010a, p. 129.

- Joshi 2010a, p. 137.

- Joshi 2010a, p. 138.

- Joshi 2010a, p. 140.

- Joshi 2010a, p. 145.

- de Camp 1975, p. 84.

- Joshi 2010a, p. 155.

- Joshi 2010a, p. 159.

- Joshi 2010a, p. 164.

- Joshi 2010a, p. 165.

- Joshi 2010a, p. 168.

- Joshi 2010a, p. 169.

- Joshi 2010a, p. 180.

- Joshi 2010a, p. 182.

- Joshi 2010a, p. 210.

- Joshi 2010a, p. 273.

- Joshi 2010a, p. 239.

- Joshi 2010a, p. 240.

- Joshi 2010a, p. 251.

- Joshi 2010a, p. 284.

- Joshi 2010a, p. 260.

- Joshi 2010a, p. 303.

- Joshi 2010a, p. 300.

- Hess 1971, p. 249.

- Hess 1971, p. 249; Joshi 2010a, p. 301.