HIV/AIDS in Lesotho

HIV/AIDS in Lesotho constitutes a very serious threat to the Basotho people and Lesotho's economic development. Since its initial detection in 1986, HIV/AIDS has spread at alarming rates in Lesotho.[1] In 2000, King Letsie III declared HIV/AIDS a natural disaster.[2] According to the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) in 2016, Lesotho's adult prevalence rate of 25% is the second highest in the world, following Eswatini.[3]

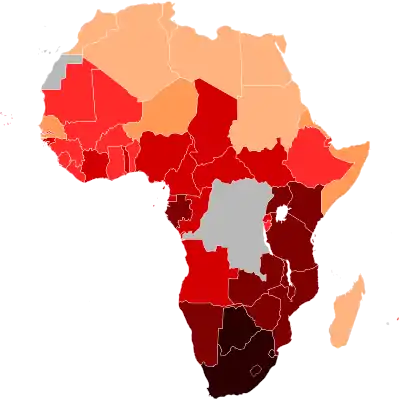

over 15% 5-15% 2-5% 1-2% 0.5-1% 0.1-0.5% not available |

HIV has affected the majority of the general population, while disproportionately affecting the rural, working-age population.[3] The spread of HIV in Lesotho is compounded by cultural practices, serodiscordancy, and gender-based violence.[4][5] Lack of developed sexual education programs in schools places the young demographic at increased risk of HIV infection.[6][7]

Over the past three decades, the Government of Lesotho, in collaboration with global organizations such as The Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria (Global Fund), World Health Organization (WHO), and President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR), has dramatically improved HIV testing and treatment coverage through comprehensive program implementation.[8][9][10] However, high levels of poverty, inequality, and stigma towards HIV remain major barriers to HIV prevention in Lesotho.[1][11][12] As such, Lesotho seeks financial aid and guidance in program reform from its neighbor South Africa, which, despite having the highest number of people living with HIV in the world,[13] has dramatically reduced costs of HIV prevention efforts in the past decade.[14]

Prevalence

Lesotho's adult prevalence rate of 25% has remained relatively constant since 2005. In 2016, there was an estimated 330,000 people living with HIV as compared to 240,000 people in 2005, and 270,000 people in 2010. Overall, HIV incidence is declining, from 30,000 new infections in 2005 to an estimated 21,000 new infections of HIV in 2016.[3]

By gender

According to the 2014 Lesotho Demographic and Health Survey (LDHS), prevalence among women has increased from 26% in 2004 to 30% in 2014, whereas male HIV prevalence has stagnated around 19% over the same time period.[15] In 2014, Lesotho's Ministry of Health and Social Welfare (MOHSW) determined the prevalence rate among young women was 10.2%, whereas among young men it was 5.9%.[8]

In 2015, pregnant women had a prevalence rate of 25.9%.[8] Men who have sex with men (MSM) had a 32.9% prevalence rate in 2016.[3]

By age

According to the 2003 HIV Sentinel Survey Report, the 25–29 age group was most affected by HIV, with prevalence of 39.1%. For the 15–19 and 20–24 age groups, median prevalence was 14.4% and 30.1%, respectively.[16] In 2014, LDHS found that 13% of young women and 6% of young men ages 15–24 were infected with HIV.[8]

In 2003, the Ministry of Health estimated that there were around 100,000 children under the age of 15 in Lesotho's 10 districts who had lost one or both parents to AIDS.[16]

By occupation

Sex workers and factory workers are disproportionately affected by HIV, with prevalence rates of 79.1% and 42.7% in 2015, respectively.[8]

Prison inmates constitute another key affected population, with a prevalence rate of 32.9% in 2015.[8]

National response

The government of Lesotho has taken concrete actions to address the epidemic since King Letsie III's declaration of HIV/AIDS as a national emergency. Establishment of the National AIDS Prevention and Control Program and the Lesotho AIDS Programme Coordinating Authority (LAPCA) under the Prime Minister’s Office accelerated national and international response to the epidemic.[5]

1980-2000

Lesotho's National AIDS Prevention and Control Program was formed in 1987.[5] However, funding and infrastructural limitations prompted the United Nations to intervene in 1992 and assist with release of sentinel surveys to monitor the spread of HIV. As such, data collection remained inconsistent until 2000.[5] It was not until 2004 that LDHS included HIV testing data to assess magnitude and patterns of HIV infection.[5]

2000-2010

LAPCA was established in 2001 to coordinate the multisectoral response to HIV/AIDS, but several factors hindered it in fulfilling its strategic role.[17] In October 2003, the government used Turning a Crisis into an Opportunity, a document constructed by a Lesotho-based United Nations interagency group, as an official working model to address the epidemic.[18] In 2005, the government passed a bill establishing the semi-autonomous National AIDS Commission (NAC) and National AIDS Secretariat (NAS) to coordinate and support strategies for the period 2005 to 2008.[2]

Lesotho committed itself to the World Health Organization (WHO) goal of having 28,000 people on antiretroviral therapy (ART) by the end of 2005.[19] In May 2004, the first comprehensive HIV/AIDS center to provide ART opened.[16] The Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria (Global Fund), international private organizations, local and international nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), and community-based organizations (CBOs) provided the mainstay of the response to HIV/AIDS, especially in the area of community mobilization.[16] Most of these operations were small and localized to specific geographical areas in urban centers. The biggest challenge was the establishment of national networks and civil society organizations on HIV/AIDS, most importantly among people living with HIV/AIDS and within the NGO network.[16] In 2005, the apparel and textile industry, Lesotho's biggest private employer, established an innovative sector-wide and comprehensive HIV workplace program through a public private partnership with the government of Lesotho, buyers, employers, and other donors.[20] In May 2009, the Apparel Lesotho Alliance to fight AIDS (ALAFA) provided close to 90% of the 42,000 employees with prevention services, and up to 80% with treatment services.[21]

Lesotho has increasingly used community mobilization and education, as well as offering HIV testing and counseling (HTC) upon individual request.[22] The burden of determining how and when people access treatment and counseling services is placed on local communities. Communities are responsible to ensure confidentiality and provide access to post-test services.[22] In 2004, only 2.7% of Basotho adults participated in HTC. However, HTC participation increased to 35% by 2011.[8]

2010-present

In 2014, the Ministry of Health initiated a new program involving provider-initiated testing and counseling, where providers traveled to homes providing HTC services instead of through individual request. However, lack of staffing and HIV test kit shortages severely impacted the program's effectiveness.[8] A research study conducted by Labhardt et al. (2014) examined the relative merits of home-based versus mobile clinic HTC services, finding that mobile clinics were more effective at detecting new HIV infections, whereas home clinics were more effective for testing those who were getting tested for the first time.[23] In 2014, 63% of Basotho men and 84% of Basotho women had been tested for HIV at least once in their life, according to LDHS.[8]

Other HIV prevention efforts spearheaded by Lesotho's Ministry of Health include preventing mother-to-child transmission (PMTCT) programs, voluntary medical male circumcision (VMMC), and condom distribution.[24]

.jpg.webp)

In 2011, the Ministry of Health successfully launched the VMMC program. By 2012, 10,400 men had undergone VMMC; by 2014, around 36,200 men had undergone treatment.[8] VMMC is most prevalent and effective among the 15-19 age group.[3] VMMC program expansion is most hindered in rural areas, where traditional initiation rituals promote circumcision of young boys.[17]

PMTCT efforts include ART for infected women throughout pregnancy, and HIV medication for babies 4–6 weeks after birth. In some cases, mothers will undergo cesarean deliveries to further prevent MTCT.[25] In 2010, WHO recommended providing ART to all pregnant women regardless of CD4 count or viral load, causing the Ministry of Health to revise its PMTCT program accordingly.[17] As a direct result, the number of infected pregnant women receiving ART increased significantly from 58% in 2009 to 89% in 2012. However, staffing and funding challenges have compromised this program's effectiveness.[8] In 2016, UNAIDS reported only 66% coverage among pregnant women.[3]

The Ministry of Health proposed a HIV prevention strategy aimed to eliminate MTCT and reduce sexual transmission of HIV by 50% by 2015. MTCT is considered eliminated when transmission rate drops below 5%, according to UNAIDS.[8] Data from Lesotho's 2015 UNAIDS Report indicates neither target was reached.[8] In 2012, MTCT rates in Lesotho stagnated around 3.5%, but subsequently increased to 5.9% in 2014.[8]

In 2015, the National Aids Commission (NAC) of Lesotho reported a distribution of 31 condoms per adult man, exceeding the United Nations Population Fund’s average of 30.[24] Male condom use with sex workers has increased from 64% in 2009 to 90% in 2014.[24] Additionally, in 2016, UNAIDS reported that 76% of adults aged 15-49 with more than one sexual partner in the past year used condoms.[3]

In June 2016, the Ministry of Health launched the “Test and Treat” initiative, where every person tested HIV positive is offered ART, regardless of CD4 count. Lesotho is the first country in sub-Saharan Africa to implement this program.[19]

Risk factors

There are various factors that place Basotho at increased risk for HIV contraction.

Cultural practices

Bulled (2015) argues that the primary risk factor for heterosexual partnerships is multiple concurrent partnerships (MCP).[5] LDHS data from 2009 indicates that bonyatsi practices, the culturally sanctioned practice of maintaining many sexual partners, continues after marriage, as 9% of women and 24.4% of men ages 30–39 had two or more sexual partners in the past year.[5] Gender differences in self-reporting of MCP is strongly influenced by social norms: men gain social standing by having multiple partners, whereas women are driven by economic need.[5] However, recent research (Tanser et al., 2011; Thorton, 2008) found that the spread of HIV was not compounded by MCP.[5]

Violence against women

Lesotho's highly patriarchal society strongly influences females’ experiences with gender-based violence, particularly in schools. Basotho communities exhibit dominant perceptions of heteronormal relations, but the social construction of male superiority places females at risk of adverse experiences through these heterosexual relations.[4] Many women and girls are placed at risk for HIV infection through gender-based violence, which commonly comes in the form of marital rape, rape, or domestic abuse. Particularly in rural areas, females are subject to this violence because they often lack social and economic power in sexual decision making.[26] These unequal power dynamics prohibit Basotho women from adopting HIV-preventative behaviors, thereby increasing their vulnerability to HIV.[26]

The prevalence of customary law in Lesotho, despite constitutional amendments in 1993 granting civil rights to all individuals, acts as a barrier to women's inheritance, ownership, and equity in marriage and other sexual relationships.[5] Customary law treats women as legal minors who are dependent on men—fathers, brothers, or husbands. As a result of the customary law, Lesotho experiences high rates of violence, inter-generational sex, and payment for sex, all of which increases an individual's risk of HIV infection.[5] Through marriage, a Basotho man becomes sexually entitled to his wife's body through payment of the bride price, making the women property of her husband.[26] In 2006, the government of Lesotho passed a civil law to counteract the gender discrimination engendered by customary law, but it was ineffective.[5] However, women rarely report these acts of violence out of fear, choosing to forget, or economic dependency on men.[26] Basotho women fear bringing shame to their families for accusing their husbands of rape. Often, women are emotionally coerced into sex through a sense of marital obligation.[26]

According to LDHS (2014), 33% of Basotho women and 40% of Basotho men affirmed the belief that under certain circumstances, a man is justified in beating his wife.[15] Furthermore, according to survey results from GenderLinks, 62% of Basotho women experienced intimate partner violence, and 37% of Basotho men perpetuated it in 2013.[27]

Serodiscordant couples

Serodiscordant relationships are a significant source of new HIV infection in Lesotho, according to Makwe and Osato (2013). The unaffected partner of serodiscordant couples is at disproportionately high risk of contracting HIV from their partner, especially when engaging in risky sexual behaviors such as pregnancy attempts.[28] HIV transmission between heterosexual serodiscordant couples, irrespective of the infected partner's gender, was found to be around 20-25% per year in 2007.[28] In 2013, serodiscordance rates in Lesotho were estimated to be around 13%.[28]

Separated, divorced, and widowed individuals are also at high risk for HIV contraction. Research conducted by De Walque and Kline (2012) has shown that unusually high HIV rates are found in remarried individuals, because many couples become serodiscordant. In Lesotho, around 32.6% of men and 45.6% of women who remarried were HIV infected between 2003-2006.[29] HIV prevalence rates among remarried women in Lesotho were especially high compared to other African countries.[29]

Interventions including consistent condom use, voluntary medical male circumcision (VMMC), and use of ART drugs can keep couples serodiscordant indefinitely. VMMC is widely recommended as a prevention strategy, with research in sub-Saharan Africa finding that female-to-male HIV transmission decreased by 38-66% over two years (Gray et al., 2007; Bailey et al., 2007).[28]

Sexual education

In Lesotho and other sub-Saharan countries, schools are often viewed as the vehicle for HIV education and prevention for the young generation. However, several internal problems greatly affect schools’ ability to change attitudes and sexual behaviors. These include lack of appropriate materials, overcrowded curriculum, lack of effective teacher training, and teachers’ embarrassment to engage students in discussions regarding HIV.[26]

According to multiple research studies conducted by Mturi and collaborators (2003; 2005), the most frequently reported reason for contraception non-use is simply lack of knowledge regarding contraception. Young people tend to use friends or the media for information on sexual health and contraception, which can be misleading sources of information.[6] Mturi (2005) found that 90% of young people in Lesotho lacked understanding of the fertile period in females’ monthly cycles.[6] Additionally, in many African societies, including Lesotho, it is considered taboo to discuss issues of sex with children. For this reason, research found that only about 20% of females and 10% of males discuss sex-related issues with their parents.[30] As parents are often embarrassed to discuss such issues with their children, they rely on schools.[6]

In Lesotho, around 90% of schools are managed by churches, and thus do not have an established sex education program. Without proper sex education, young people are at risk for HIV contraction.[6] As a result, Lesotho's Ministry of Education proposed the Population and Family Life Education (POP/FLE) initiative to introduce sex education curriculum into schools.[6]

Difficulties in treatment

There are several obstacles to effective HIV/AIDS treatment in Lesotho.

Stigma and discrimination

There exists a strong cultural stigma against HIV diagnoses in many countries of Sub-Saharan Africa, including Lesotho, which leads to discrimination against those infected. Discrimination can take the form of gossip, verbal and physical abuse, or social exclusion.[12] Access to treatment, prevention, and support services is greatly hindered by discrimination.[12] In 2014, 4% of HIV-infected Basotho reported denied access to healthcare services in the past year, while 5.5% reported denied access to family planning services in the same time period.[12] Discrimination can negatively impact employment opportunities as well as workers' livelihoods. In 2016, 13.9% of Basotho reported that they would not buy vegetables from a vendor living with HIV, according to UNAIDS.[3]

Political factionalism

Turkon (2008) suggested that efforts to combat the HIV/AIDS epidemic in Lesotho are undermined by strong partisan divisions in rural communities. UNAIDS has expressed hope that the HIV/AIDS crisis will be the catalyst for Basotho communities to transcend partisan lines and work together as a unit.[11]

Political factions in Lesotho arise from vested interest in governmental control.[11] The people of Lesotho place little trust in the Basotho's political elite to uphold communal values or demonstrate hierarchical reciprocity. This is in part due to political instability present in the country. While the government of Lesotho is a constitutional monarchy, with the Prime Minister of Lesotho heading the government, a system of chieftaincy informally governs the rural areas.[31] The chieftaincy operates as an administrative hierarchy, responsible for governing the colonial structure of wards and districts in rural communities. The chieftaincy system as a whole receives support from villagers, while individual chiefs are often heavily criticized for corrupt practices, including dereliction, favoritism, and bribery.[31] Nevertheless, partisan divisions do not only exist between chief and commoner. They often manifest as antagonistic relationships between neighbors in the same village.[11] As a result, community-based approaches to HIV/AIDS treatment are often unsuccessful.[11]

Lack of resources

Lack of proper resources and lack of access to resources compromises efficacy of HIV treatments. Healthcare centers often lack basic equipment and drug supplies, or are chronically understaffed.[32] Furthermore, travel distance to healthcare centers can be financially and physically burdensome for many, particularly rural patients. Round-trip transportation to the healthcare clinic and cost of treatment, totaling about $10, prevents a problem for many Basotho.[32] Moreover, follow-up visits following initial treatment is cost-prohibitive. In 2014, LDHS found that 38% of rural patients walked for more than two hours to reach their healthcare facility, whereas only 3% of urban patients walked.[15] Those too ill to travel alone require accompaniment, at the risk of worsening existing health conditions.[32]

Health conditions

Preexisting or concurrent health conditions, both communicable and chronic, can increase an individual's risk of HIV contraction as well as exacerbate the progression of the disease.

Malnutrition

Malnutrition may be the greatest obstacle to effective HIV treatment. Starvation allows rapid progression of HIV by undermining the body's natural defense mechanisms[32] and promoting viral replication.[33] This can lead to increased toxicity of HIV/AIDS treatment drugs.[32] General maternal malnutrition and vitamin deficiencies can increase risk of MTCT.[33] In 2015, the World Bank estimated that 11% of Lesotho's population was undernourished.[34]

Parasitic infections

Parasitic infections, commonly in the form of malaria infections, intestinal parasites, or schistosomiasis, compromise the immune system and exacerbate malnutrition. Malaria is estimated to increase HIV viral load by seven to ten times.[33] Consequently, people with malaria are at increased risk of transmitting HIV to partners. There is very little data on malaria prevalence in Lesotho.[15][35] In contrast, prevalence rates of schistosomiasis in Lesotho were estimated to be 8.3% in 2015.[36] Worms that cause schistosomiasis live in streams and lakes, which women often frequent through activities such as bathing, washing clothes, or collecting water.[33] Schistosomiasis promotes HIV transmission through genital lesions and inflammation. It is estimated to triple women's risk of HIV infection.[33]

Tuberculosis co-infection

Recent increases in the number of tuberculosis (TB) co-infections, particularly multi drug resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB), in HIV-infected Basotho hinders effective HIV treatment. The risk of contracting TB is much greater for those already infected with HIV.[37]

In 2014, 74% of Basotho infected with TB tested positive for HIV.[8] In 2015, it was estimated that there was about 12,000 incident tuberculosis cases among those living with HIV.[3] Lesotho, among several other sub-Saharan countries, struggles to control the TB epidemic. Reasons include competing national health system priorities (such as the HIV/AIDS epidemic), and the toll of TB/HIV co-infection on healthcare workers. Delayed diagnosis, inadequate initial treatment, and prolonged infectiousness of TB further exacerbate the severity of the epidemic.[37]

Adherence to treatment

Adherence to treatment, most commonly ART, remains a large barrier to effective provision of HIV treatment. In 2016, about 53% of adults living with HIV in Lesotho were receiving ART.[3] Lesotho has seen a decline in access to ART medication between 2010 and 2016, as 66% of pregnant Basotho women living with HIV had access to ART medicines in 2016, as compared to 72% in 2010.[3]

Once a patient seeks out initial treatment for HIV, follow-up visits are critical to improve and maintain a patient's clinical, immunological, and virological outcome. Adherence to ART drugs delays onset of drug resistance, treatment failure, and subsequent necessity to use a different drug treatment.[9] Maintaining proper adherence to treatment involves meticulous processes, such as taking the correct amount of medication in the specific, regimented manner mandated by health professionals. Drug treatments must also be stored properly.[9]

Costs of medication and continual treatment are prohibitive for many Basotho. Other barriers to adherence include lack of transportation to healthcare facilities, lack of access to medication refills, or inconsistency of caregiver.[9] Cultural attitudes of stigma toward HIV diagnosis in Lesotho often leaves those infected without social support, which can negatively impact adherence.[12]

Economic impact

HIV/AIDS has had a devastating economic impact in Lesotho at both the macroeconomic level and the microeconomic level. Increased morbidity and mortality rates has reduced living standards and has exacerbated poverty, inequality, and unemployment levels throughout the country.[17]

Macroeconomic

From 1993 to 1998, HIV/AIDS response cost Lesotho's government an estimated 151.2 million Maloti.[38] In 2016 alone, UNAIDS estimated HIV/AIDS costs to be $124 million[3] (around M1.7 billion[39]). Domestic expenditure was nearly equal to international expenditure.[3] Lesotho's government relies heavily on international sources of funding for HIV response, from organizations such as The Global Fund, PEPFAR, and UN agencies.[10]

HIV has decreased growth in many of Lesotho's economic sectors, including the agricultural sector,[1] which holds an estimated 86% of the labor force.[40] Death from AIDS reduces the number of productive workers in the workforce, diminishing worker productivity as younger, less experienced workers replace experienced laborers.[41] Many Basotho migrate to South Africa to work; as they fall ill and return home, money inflows to the country decrease.[41]

HIV negatively impacts educational outcomes, mostly in Lesotho's rural populations where prevalence is highest. Children, particularly girls, are less likely to attend school or complete primary school because they are expected to care for sick family members or younger siblings orphaned by AIDS.[7] Falling school retention rates and decreased worker productivity may have a long-term, widespread effect on human capital investment and future economic growth of Lesotho.[42]

Microeconomic

HIV incurs several costs on caregivers and households. Caregivers, while mostly women, can be children and the elderly as well. Costs of treatment and management of HIV, including the purchase of scarce items such as water, disinfectants, and soaps, consumes about one-third of household incomes.[43] Akintola (2008) found that volunteer caregivers in Lesotho reported giving their own personal items or food to patients due to insufficient income.[43] As such, households where women combine the roles of caregiver, head of household, and breadwinner are common in Lesotho and other sub-Saharan countries.[43]

Caregiving can be physically and emotionally distressing to caregivers, as ill patients require continuous, demanding care. Many caregivers, particularly working-age caregivers, lose the opportunity to earn a primary income or engage in other activities due to this demanding role.[43]

See also

References

- Central Bank of Lesotho, comp. Economic Impact of HIV/AIDS in Lesotho. Report. March 2004. https://www.centralbank.org.ls/images/Publications/Research/Reports/MonthlyEconomicReviews/2004/Economic_Review_Mar_04.pdf.

- National AIDS Commission, Lesotho. COORDINATION FRAMEWORK FOR THE NATIONAL RESPONSE TO HIV AND AIDS. Publication. 2007. Accessed November 25, 2017. http://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---ed_protect/---protrav/---ilo_aids/documents/legaldocument/wcms_126753.pdf.

- UNAIDS. UNAIDS Data 2017, 2017, pp. 32. Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS.

- Morojele, Pholoho. “Gender Violence: Narratives and Experiences of Girls in Three Rural Primary Schools in Lesotho.” Agenda: Empowering Women for Gender Equity, no. 80, 2009, pp. 80–87. JSTOR, JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/27868967.

- Bulled, Nicola. Prescribing HIV Prevention: Bringing Culture into Global Health Communication. Vol. 1. N.p.: Left Coast Press, 2015. Print.

- Mturi, Akim J., and Monique M. Hennink. “Perceptions of Sex Education for Young People in Lesotho.” Culture, Health & Sexuality, vol. 7, no. 2, 2005, pp. 129–143. JSTOR, JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/4005445.

- Nyabanyaba, Thabiso. “Improving the Quality of Education among Rural Learners through the Use of Open and Flexible Approaches in Lesotho’s Secondary Schools.” Journal of Higher Education in Africa / Revue De L'enseignement Supérieur En Afrique, vol. 13, no. 1-2, 2015, pp. 111–131. JSTOR, JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/jhigheducafri.13.1-2.111.

- Lesotho Ministry of Health and Social Welfare (MOHSW) “Global AIDS Response Country Progress Report: January -December 2014.” 2015, pp. 1-36, UNAIDS.

- Ramatlapeng, Mphu. “Working Draft—Lesotho National ART Guidelines.” Consolidated Guidelines on the Use of Antiretroviral Drugs for Treating and Preventing Infection, 2004, pp. 1-156. Lesotho Ministry of Health and Social Welfare (MOHSW), World Health Organization, https://www.who.int/hiv/pub/guidelines/lesotho_art.pdf.

- Lesotho Country Operational Plan (COP) 2016: Strategic Direction Summary, 2016, pp. 1-69. Lesotho Ministry of Health and Social Welfare (MOHSW), President’s Emergency Plan for Aids Relief (PEPFAR), https://www.pepfar.gov/documents/organization/257640.pdf

- Turkon, David. “Commoners, Kings, and Subaltern: Political Factionalism and Structured Inequality in Lesotho.” Political and Legal Anthropology Review, vol. 31, no. 2, 2008, pp. 203–223. JSTOR, JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/24497353.

- “Lesotho 2014.” The People Living with HIV Stigma Index, 2014, pp. 1-42. Lesotho Network of People Living with HIV and AIDS (LENEPWHA).

- The Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS). 2017. Ending AIDS: Progress Towards 90-90-90. Report. Geneva: UNAIDS.

- Barton-Knott, Sophie. June 2013. Around 10 million people living with HIV now have access to antiretroviral treatment. Press Report. Geneva: The Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS).

- Ministry of Health [Lesotho] and ICF International. Lesotho Demographic and Health Survey 2014, 2006, pp. 1-538. Maseru, Lesotho: Ministry of Health and ICF International.

- Bowsky, Sara. US Government Rapid Appraisal for HIV/AIDS Program Expansion: Lesotho. Report. 2004. Accessed November 25, 2017. http://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/Pdacf093.pdf.

- Lesotho Ministry of Health and Social Welfare (MOHSW) “Global AIDS Response Country Progress Report: January 2010-December 2011.” 2012, pp. 1-106, UNAIDS, http://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/country/documents//file,68395,fr..pdf

- Sprague, Courtenay (2005). "New Strategies in the Battle against HIV/AIDS". African Studies Review. 48 (3): 143. doi:10.1353/arw.2006.0042. JSTOR 20065147.

- "Guideline on when to start antiretroviral therapy and on pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV". World Health Organization. September 2015.

- Overseas Development Institute. Aid for Trade in Lesotho: ComMark’s Lesotho Textile and Apparel Sector Programme. Publication. 2009. Accessed November 25, 2017. https://www.odi.org/sites/odi.org.uk/files/odi-assets/publications-opinion-files/5948.pdf.

- "Apparel Lesotho Alliance to Fight Aids (ALAFA) Project." DAI: International Development. Accessed November 25, 2017. https://www.dai.com/our-work/projects/lesotho-apparel-lesotho-alliance-fight-aids-alafa-project.

- “HIV Testing, Treatment and Education Campaigns: Lesotho, Botswana and Swaziland.” Reproductive Health Matters, vol. 14, no. 27, 2006, pp. 229–229. JSTOR, JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/3775938.

- Labhardt, N.D. et al. (2014). Home-Based Versus Mobile Clinic HIV Testing and Counseling in Rural Lesotho: A Cluster-Randomized Trial. PLOS Medicine.

- Prevention Gap Report 2016. Report. UNAIDS, 2017. Accessed November 25, 2017. http://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/2016-prevention-gap-report_en.pdf.

- "Understanding HIV/AIDS". US Department of Health and Human Services. 2017.

- Motalingoane-Khau, Mathabo. “'But He Is My Husband! How Can That Be Rape?': Exploring Silences around Date and Marital Rape in Lesotho.” Agenda: Empowering Women for Gender Equity, no. 74, 2007, pp. 58–66. JSTOR, JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/27739343.

- Chipatiso, Linda Musariri, Mercilene Machisa, Violet Nyambo, and Kevin Chiramba.Gender-Based Violence Indicators Study: Lesotho. Gender Links. Gender Links: For Equality and Justice. 2014. Accessed November 25, 2017. http://genderlinks.org.za/wp-content/uploads/imported/articles/attachments/20068_final_gbv_ind_lesotho.pdf.

- Makwe, Christian C., and Osato F. Giwa-Osagie. “Sexual and Reproductive Health in HIV Serodiscordant Couples.” African Journal of Reproductive Health / La Revue Africaine De La Santé Reproductive, vol. 17, no. 4, 2013, pp. 99–106. JSTOR, JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/24362091.

- De Walque, Damien, and Rachel Kline. “The Association Between Remarriage and HIV Infection in 13 Sub-Saharan African Countries.” Studies in Family Planning, vol. 43, no. 1, 2012, pp. 1–10. JSTOR, JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/23409375.

- Mturi, Akim J. “Parents' Attitudes to Adolescent Sexual Behaviour in Lesotho.” African Journal of Reproductive Health / La Revue Africaine De La Santé Reproductive, vol. 7, no. 2, 2003, pp. 25–33. JSTOR, JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/3583210.

- Coplan, David B., and Tim Quinlan. "A Chief by the People: Nation versus State in Lesotho." Africa: Journal of the International African Institute 67, no. 1 (1997): 27-60. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1161269.

- McMurchy, Dale (2005). "OHAfrica: Initial Learnings as the OHAfrica Team Commences Its Work at an HIV Clinic in Lesotho". Healthcare Quarterly. 8 (2): 14–15. doi:10.12927/hcq..17050.

- Stillwaggon, Eileen (2008). "Race, Sex, and the Neglected Risks for Women and Girls in Sub-Saharan Africa". Feminist Economics. 14 (4): 67–86. doi:10.1080/13545700802262923.

- World Bank Group. "Prevalence of Undernourishment (% of Population)." World Bank. Accessed November 19, 2017. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SN.ITK.DEFC.ZS.

- WHO, and United Nations. "Lesotho: WHO Statistical Profile." World Health Organization. Accessed November 19, 2017. https://www.who.int/gho/countries/lso.pdf.

- Lai, YS; et al. (2015). "Spatial distribution of Schistosomiasis and Treatment Needs in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Systematic Review and Geostatistical Analysis". The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 15 (8): 927–40. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(15)00066-3. PMID 26004859.

- Wells, Charles D., et al. “HIV Infection and Multidrug-Resistant Tuberculosis: The Perfect Storm.” The Journal of Infectious Diseases, vol. 196, 2007, pp. s86–s107. JSTOR, JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/30086663.

- McMurchy, Dale (1997). "The economic impact of HIV / AIDS in Lesotho". AIDS Analysis Africa. 7 (4): 11–12. PMID 12157888.

- "XE Currency Converter: USD to LSL." XE Currency Converter. Accessed November 25, 2017. http://www.xe.com/currencyconverter/convert/?Amount=124%2C000%2C000&From=USD&To=LSL.

- United States of America. Central Intelligence Agency. Lesotho. Accessed November 25, 2017. CIA World Factbook.

- Sackey, James, and Tejaswi Raparla. "Lesotho: The Development, Impact of HIV/AIDS-Selected Issues and Options." World Bank Report 21103-LSO (2000).

- Fortson, Jane G. “MORTALITY RISK AND HUMAN CAPITAL INVESTMENT: THE IMPACT OF HIV/AIDS IN SUB-SAHARAN AFRICA.” The Review of Economics and Statistics, vol. 93, no. 1, 2011, pp. 1–15. JSTOR, JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/23015916.

- Akintola, Olagoke (2008). "Unpaid HIV/AIDS Care in Southern Africa: Forms, Context, and Implications". Feminist Economics. 14 (4): 117–147. doi:10.1080/13545700802263004.