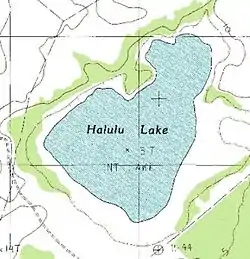

Halulu Lake

Halulu Lake is a lake in the south central region of the island of Niʻihau (the smallest inhabited island in the chain).[1] It is the largest (non-intermittent) natural lake in the Hawaiian Islands and ranks third in size after Hālaliʻi Lake (also on Niʻihau) and Keālia Pond (on Maui) which are intermittent bodies of water.[2][3]

| Halulu Lake | |

|---|---|

| |

Halulu Lake | |

| Location | Niʻihau |

| Coordinates | 21.868°N 160.207°W |

| Catchment area | 182 acres (74 ha) |

| Basin countries | United States |

The lake measures around 182 acres (74 ha) during the rainy seasons. During dry periods on the arid island, the shallow lake shrinks due to effect of evaporation.[4][5] Other sources give it the measurement of 371 acres (150 ha).[3]

According to Hawaiian linguists Mary Kawena Pukui, Samuel H. Elbert, and Esther T. Mookini, the lake shares its name with the land division of Halulu on the island and probably originated from the man-eating halulu bird of Hawaiian mythology.[6] Hālaliʻi and Halulu were also the names of important Hawaiian high chiefs (aliʻi) of the island of Niʻihau.[7]

Prior to the attack on Pearl Harbor during World War II, Niʻihau owner and rancher Aylmer Francis Robinson plowed trenches using mules and tractors into the lakes and surrounding lands on Niʻihau to prevent Japanese planes from landing and using the island as a military airfield. These efforts led to the crash landing of Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service pilot Shigenori Nishikaichi during the Niihau incident. Many of the furrows are still visible today on the island.[8][9]

The lake provides natural wetland habitats for Hawaiian bird species including the ʻalae keʻokeʻo (Hawaiian coot), aeʻo (Hawaiian stilt) and koloa maoli (Hawaiian duck).[8][10] The lake is also home to mullets which naturally enter the lake from the sea through lava tubes when they are young.[11] In ancient Hawaii, a kapu forbade Hawaiians from catching the fish in the lake except during harvest time. Modern day Niihauans use the lakes and ponds on the island for mullet farming, bringing the baby pua mullets from the sea in barrels.[11] The grown fish are later sold at market on Kauaʻi and Oʻahu.[11]

See also

References

- Doak 2003, pp. 20–21.

- Morgan 1996, p. 205.

- Doak 2003, p. 21.

- Tava & Keale 1990, p. 95.

- Juvik, Juvik & Paradise 1998, p. 6.

- Pukui, Elbert & Mookini 1974, p. 39.

- Tava & Keale 1990, p. 13.

- Young 2012.

- Gobetz 2010.

- Fisher 1951, pp. 31–42.

- Tava & Keale 1990, pp. 66–67.

Bibliography

- Doak, Robin Santos (2003). Hawaii: The Aloha State. Milwaukee: World Almanac Library. ISBN 978-0-8368-5149-6. OCLC 302362168.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Fisher, Harvey I. (January 1951). "The Avifauna of Niihau Island, Hawaiian Archipelago" (PDF). The Condor. Santa Clara, CA: Cooper Ornithological Club. 53 (1): 31–42. doi:10.2307/1364585. OCLC 4907610428.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gobetz, Wally (May 26, 2010). "Oʻahu – Honolulu – Ford Island: Pacific Aviation Museum – Cletrac Tractor". Flickr. Retrieved May 16, 2017.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Juvik, James O; Juvik, Sonia P; Paradise, Thomas R. (1998). Atlas of Hawaiʻi. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-2125-8. OCLC 246132868.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Morgan, Joseph (1996). Hawaiʻi, a Unique Geography. Honolulu: Bess Press. ISBN 978-1-57306-021-9. OCLC 249274291.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Pukui, Mary Kawena; Elbert, Samuel H.; Mookini, Esther T. (1974). Place Names of Hawaii. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-0524-1. OCLC 1042464.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Tava, Rerioterai; Keale, Moses K. (1990). Niihau: The Traditions of a Hawaiian Island. Honolulu: Mutual Publishing Company. OCLC 21275453.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Young, Peter T. (August 22, 2012). "Ni'ihau Lakes". Image of Old Hawaiʻi. Hoʻokuleana LLC. Retrieved May 16, 2017.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)