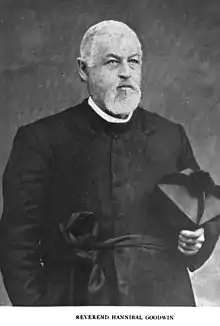

Hannibal Goodwin

Hannibal Williston Goodwin (April 21, 1822 – December 31, 1900), patented a method for making transparent, flexible roll film out of nitrocellulose film base, which was used in Thomas Edison's Kinetoscope, an early machine for viewing motion pictures.[3]

Hannibal Goodwin | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | April 21, 1822 |

| Died | December 31, 1900 (aged 78) |

| Occupation | Episcopal Clergyman,[1] Inventor |

| Known for | inventing celluloid photofilm |

| Spouse(s) | Rebecca[2] |

Biography

Goodwin was born on April 21, 1822 in Ulysses, New York and was raised on a farm.[1] He began taking college classes at Yale Law School in 1844, then Wesleyan University, and finally earned his degree in 1848 at Union College. Goodwin began studying at Union Theological Seminary in New York City to become a Episcopal preacher.[2] After taking positions in Pennsylvania and California, Goodwin settled down as the fifth rector of the House of Prayer Church in Newark, Essex County, New Jersey.[2]

Goodwin was motivated to search for a non-breakable, and clear substance on which he could place the images he utilized in his Biblical teachings.[2][4] He set up a chemistry lab in the attic of the Plum house rectory and sawed a five foot hole in the roof for better sunlight.[2]:335 On May 2, 1887, the year Goodwin retired from the church he had served for twenty years, he filed a patent for "a photographic pellicle and process of producing same ... especially in connection with roller cameras", but the patent was not granted until 13 September 1898.[5] In the meantime, George Eastman had already started production of roll-film using his own process.[6][7]

In 1900, Goodwin set up the Goodwin Film and Camera Company, but before film production had started he was involved in a street accident near a construction site and died from a broken leg and Pneumonia on December 31, 1900.[2]

Legacy

Goodwin's patent was sold to Ansco who successfully sued Eastman Kodak for infringement of the patent and was awarded $5 million (over $120 million in 2020) on March 10, 1914.[2][8]

References

- "It was Today". The Record. Hackensack, New Jersey. 30 April 1945. p. 20. Retrieved 24 January 2021 – via Newspapers.com

.

. - Ramirez, Ainissa (April 7, 2020). The Alchemy of Us (1 ed.). Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press. pp. 93–101. ISBN 9780262542265. LCCN 2019029157. OCLC 1155701808. Retrieved 24 January 2021.

- Greg Hatala (17 December 2013). "Made in Jersey: Flexible film - before digital, we waited to see what developed". The Star-Ledger. Retrieved 2 February 2014.

- "Forgotten Inventor". The Beaver County News. 3 July 1947. p. 8. Retrieved 24 January 2021 – via Newspapers.com

.

. - U.S. Patent 610,861

- Alfred, Randy (2 May 2011). "May 2, 1887: Celluloid-Film Patent Ignites Long Legal Battle". Wired. Retrieved 29 August 2017.

- Orrock, Ray (20 July 1973). "Of Cinema and Celluloid". The Argus. Fremont, California. p. 15. Retrieved 24 January 2021 – via Newspapers.com

.

. - "Kodak Concern to Make Big Payment to Goodwin Company". New York Times. March 27, 1914. Retrieved 2010-09-18.

A settlement has been reached between the Goodwin Film and Camera Company and the Eastman Kodak Company concerning the suit brought in the Federal District Court by the former for an accounting of the profits derived from the sale of photographic films prepared according to the patent taken out by the late Rev. Hannibal Goodwin of Newark in 1898. The details of it have not been announced, but it is understood to provide for tile payment of a large sum of money by ...

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hannibal Goodwin. |