Harmodius and Aristogeiton

Harmodius (Greek: Ἁρμόδιος, Harmódios) and Aristogeiton (Ἀριστογείτων, Aristogeíton; both died 514 BC) were two ancient Athenian lovers that became known as the Tyrannicides (τυραννόκτονοι, tyrannoktonoi), the preeminent symbol of democracy to ancient Athenians, after they committed an act of political assassination at the 514 BC Panathenaic Festival. They assassinated Hipparchus, thought to be the last Peisistratid tyrant, though according to Thucydides Hipparchus was not a tyrant but a minister. They also planned to kill the real tyrant of Athens, Hippias, but were unsuccessful.

Background

The two principal historical sources covering Harmodius and Aristogeiton are the History of the Peloponnesian War (VI, 56–59) by Thucydides, and The Constitution of the Athenians (XVIII) attributed to Aristotle or his school. However, their story is documented by a great many other ancient writers, including important sources such as Herodotus and Plutarch. Herodotus[1] claimed that Harmodius and Aristogeiton presumably were "Gephyraeans" (el) i.e. Boeotians of Syrian or Phoenician origin. Plutarch, in his book On the malice of Herodotus criticized Herodotus for prejudice and misrepresentation and he argued that Harmodius and Aristogeiton were Euboeans or Eretrians.[2]

Peisistratus had become tyrant of Athens after his third attempt in 546/7 BC. In Archaic Greece, the term tyrant did not connote malevolence. A tyrant was simply one who had seized power and ruled outside of a state's constitutional law. When Peisistratus died in 528/7 BC, his son Hippias took the position of Archon and became the new tyrant of Athens, with the help of his brother, Hipparchus, who acted as the minister of culture. The two continued their father's policies, but their popularity declined after Hipparchus began to abuse the power of his position.

Thucydides offers this explanation for Harmodios and Aristogeiton's actions in Book VI: Hipparchus was rejected by Harmodius, for whom he had unrequited feelings. Hipparchus invited Harmodius' young sister to be the kanephoros (to carry the ceremonial offering basket) at the Panathenaea festival, then publicly chased her away on the pretext she was not a virgin, as required. This publicly shamed Harmodius' family. With his lover Aristogeiton, Harmodius resolved to assassinate both Hippias and Hipparchus and thus to overthrow the tyranny.[3] Harmodios and Aristogeiton successfully killed Hipparchus during the 514 BC Panathenaia, but Hippias survived and remained in power. In the four years between Hipparchus' assassination and the deposition of the Pisistratids, Hippias became an increasingly oppressive tyrant.

According to Aristotle, it was Thessalos, the hot-headed son of Peisistratus' Argive concubine, and thus half-brother to Hipparchus, who was the one to court Harmodius and drive off his sister.[4]

The assassination

The plot – to be carried out by means of daggers hidden in the ceremonial myrtle wreaths on the occasion of the Panathenaic Games – involved a number of other co-conspirators. Thucydides claims that this day was chosen because during the Panathenaic festival, it was customary for the citizens taking part in the procession to go armed, while carrying weapons on any other day would have been suspicious.[5] Aristotle disagrees, asserting that the custom of bearing weapons was introduced later, by the democracy.[6]

Seeing one of the co-conspirators greet Hippias in a friendly manner on the assigned day, the two thought themselves betrayed and rushed into action, ruining the carefully laid plans. They managed to kill Hipparchus, stabbing him to death as he was organizing the Panathenaean processions at the foot of the Acropolis. Herodotus expresses surprise at this event, asserting that Hipparchus had received a clear warning concerning his fate in a dream.[1] Harmodius was killed on the spot by spearmen of Hipparchus' guards, while Aristogeiton was arrested shortly thereafter. Upon being told of the event, Hippias, feigning calm, ordered the marching Greeks to lay down their ceremonial weapons and to gather at an indicated spot. All those with concealed weapons or under suspicion were arrested, gaining Hippias a respite from the uprising.

Thucydides' identification of Hippias as the two's purported main target, rather than Hipparchus who was Aristogeiton's rival erastes, has been suggested as a possible indication of bias on his part.[7]

Aristogeiton's torture

Aristotle in the Constitution of Athens preserves a tradition that Aristogeiton died only after being tortured in the hope that he would reveal the names of the other conspirators. During his ordeal, personally overseen by Hippias, he feigned willingness to betray his co-conspirators, claiming only Hippias' handshake as guarantee of safety. Upon receiving the tyrant's hand he is reputed to have berated him for shaking the hand of his own brother's murderer, upon which the tyrant wheeled and struck him down on the spot.[8]

Leæna

Likewise, there is a later[9] tradition that Aristogeiton (or Harmodius)[10] was in love with a courtesan (see hetaera) by the name of Leæna (Λέαινα – meaning lioness) who also was kept by Hippias under torture – in a vain attempt to force her to divulge the names of the other conspirators – until she died. One version of her story holds that previous to being tortured she had bitten off her tongue, afraid that her resolve would break from the pain of the torture. Another is that the Athenians, unwilling to honour a courtesan, placed a statue of a lioness without a tongue in the vestibule of the Acropolis simply to honor her fortitude in maintaining silence.[11][12][13] The statue was made by the sculptor Amphicrates.[14] It was also in her honor that Athenian statues of Aphrodite were from then on accompanied by stone lionesses [after Pausanias].[15] Leæna's story is only told in later antiquity sources and is likely spurious.[16]

Aftermath

His brother's murder led Hippias to establish an even stricter dictatorship, which proved very unpopular and was overthrown, with the help of an army from Sparta, in 508. This was followed by the reforms of Cleisthenes, who established a democracy in Athens.

Apotheosis

Subsequent history came to identify the figures of Harmodius and Aristogeiton as martyrs to the cause of Athenian freedom, possibly for political and class reasons, and they became known as "the Liberators" (eleutherioi) and "the Tyrannicides" (tyrannophonoi).[17] According to later writers, descendants of Harmodius and Aristogeiton's families were given hereditary privileges, such as sitesis (the right to take meals at public expense in the town hall), ateleia (exemption from certain religious duties), and proedria (front-row seats in the theater).[18]

A number of years after the event, it had become a received tradition among the Athenians to believe that Hipparchus was the elder of the brothers, and to fashion him as the tyrant.[19]

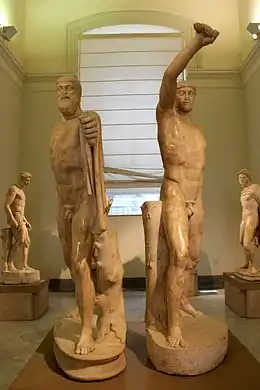

Statues and artistic depictions

After the establishment of democracy, Cleisthenes commissioned the sculptor Antenor to produce a bronze[20] statue group of Harmodius and Aristogeiton. It was the first commission of its kind, and the very first statue to be paid for out of public funds, as the two were the first Greeks considered by their countrymen worthy of having statues raised to them.[21] According to Pliny the Elder, it was erected in the Kerameikos in 509,[22] as part of a cenotaph of the heroes. However, a far more probable location is in the Agora at Athens, and many later authors such as Pausanius and Timaeus attest to this. Annual offerings (enagismata) were presented there by the polemarch, the Athenian minister of war.[23] There it stood alone as special laws prohibited the erection of any other statues in their vicinity. Upon its base was inscribed a verse by the poet Simonides:

A marvelous great light shone upon Athens when Aristogeiton and Harmodios slew Hipparchus.[24]

The statue was taken as war booty in 480 BC by Xerxes I during the early Greco-Persian Wars and installed by him at Susa. As soon as the Greeks vanquished the Persians at Salamis, a new statue was commissioned. It was sculpted this time by Kritios and Nesiotes, and set up in 477/476 BC.[25][26] It is the one which served as template for the group we possess today, which was found in the ruins of Hadrian's villa and is now in Naples. According to Arrian,[27] when Alexander the Great conquered the Persian empire, in 330, he discovered the statue at Susa and had it shipped back to Athens.[28] When the statue, on its journey back, arrived at Rhodes it was given divine honors.[29]

Several comments of the ancients regarding the statue have come down to us. When asked, in the presence of Dionysius, the tyrant of Syracuse, which type of bronze was the best, Antiphon the Sophist replied,

That of which the Athenians made the statues of Harmodius and Aristogeiton."[30]

Lycurgus, in his oration against Leocrates, asserts that,

In the rest of Greece you will find statues erected in the public places to the conquerors in the games, but amongst you they are dedicated only to good generals, and to those who have destroyed tyrants.[31]

Other sculptors made statues of the heroes, such as Praxiteles, who made two, also of bronze.[32]

The statue group has been seen, in modern times, as an invitation to identify erotically and politically with the figures, and to become oneself a tyrannicide. According to Andrew Stewart, the statue

not only placed the homoerotic bond at the core of Athenian political freedom, but asserted that it and the manly virtues (aretai) of courage, boldness and self-sacrifice that it generated were the only guarantors of that freedom’s continued existence.[33]

The configuration of the group is duplicated on a painted vase, a Panathenaic amphora from 400,[34] and on a bas-relief on the Elgin throne, dated to ca. 300.[35]

Skolia

Another tribute to the two heroes was a hymn (skolion) praising them for restoring isonomia (equal distribution of justice) to the Athenians. The skolion may be referred to 500 BC or thereabouts,[36]

and is ascribed to Callistratus, an Athenian poet known only for this work. It is preserved by Athenaeus.[37] Its popularity was such that

at every banquet, nay, in the streets and in the meanest assembly of the common people, that convivial ode was daily sung,[38]

When sung, the singer would hold a branch of myrtle in his hand.[39] This ode has been translated by many modern poets such as Edgar Allan Poe, who composed his Hymn to Aristogeiton and Harmodius in 1827.[40] The following translation was judged to be the best and most faithful of a number of versions attempted in Victorian England.[41]

In myrtles veil'd will I the falchion wear,

For thus the patriot sword

Harmodius and Aristogiton bare,

When they the tyrant's bosom gored,

And bade the men of Athens be

Regenerate in equality.

Oh! beloved Harmodius! never

Shall death be thine, who liv'st for ever.

Thy shade, as men have told, inherits

The islands of the blessed spirits,

Where deathless live the glorious dead,

Achilles fleet of foot, and Diomed.

In myrtles veil'd will I the falchion wear,

For thus the patriot sword

Harmodius and Aristogiton bare,

When they the tyrant's bosom gored;

When in Minerva's festal rite

They closed Hipparchus' eyes in night.

Harmodius' praise, Aristogiton's name,

Shall bloom on earth with undecaying fame;

Who with the myrtle-wreathed sword

The tyrant's bosom gored,

And bade the men of Athens be

Regenerate in equality.[42]

Importance to the erastes-eromenos tradition

The story of Harmodius and Aristogeiton, and its treatment by later Greek writers, is illustrative of attitudes to pederasty in ancient Greece. Both Thucydides and Herodotus describe the two as lovers, their love affair was styled as moderate (sophron) and legitimate (dikaios).[43] Further confirming the status of the two as paragons of pederastic ethics, a domain forbidden to slaves, a law was passed prohibiting slaves from being named after the two heroes.[44]

The story continued to be cited as an admirable example of heroism and devotion for many years. In 346 BC, for example, the politician Timarchus was prosecuted (for political reasons) on the grounds that he had prostituted himself as a youth. The orator who defended him, Demosthenes, cited Harmodius and Aristogeiton, as well as Achilles and Patroclus, as examples of the beneficial effects of same-sex relationships.[45] Aeschines offers them as an example of dikaios erōs, "just love", and as proof of the boons such love brings the lovers – who were both improved by love beyond all praise – as well as to the city.[46]

Notes

- Herodotus 1920, Book V. 55

- Plutarch 1878, The Malice of Herodotus.

- Lavelle 1986, p. 318.

- Aristotle, XVIII, 2.

- Thucydides, VI, 56, 2.

- Aristotle, XVIII, 4.

- Lavelle 1993, p. .

- Aristotle 1952, 18.1.

- Konstantinos Kapparis (2018). Prostitution in the Ancient Greek World. De Gruyter. p. 99. ISBN 978-3110556759.

- Alciato, Emblemata; EMBLEMA XIII

Cecropia effictam quam cernis in arce Leaenam,

Harmodii (an nescis hospes?) amica fuit.

Sic animum placuit monstrare viraginis acrem

More ferae, nomen vel quia tale tulit.

Quòd fidibus contorta, suo non prodidit ullum

Indicio, elinguem reddidit Iphicrates. - Polyaenus, VIII.xlv.

- Pliny the Elder, XXXIV 19.72.

- Plutarch 1878g, On Talkativeness 505E.

- Smith 1870, p. 149.

- Athenaeus, XIII, 70.

- Kapparis (2018), pp. 100–101. "This story is a revision of the traditional tale in order to explain the bronze lioness with the missing tongue, and probably also to gloss over the uncomfortable feeling of later antiquity audiences over the homosexual relationship of those two most glorious heroes from the Athenian past."

- Law 2009, p. 18.

- Demosthenes. Against Leptines. p. 503f.

- Demosthenes & Kennedy 1856, p. 264.

- Lucian refers to this "χαλκοῦς" (of copper) statue in Περὶ Παρασίτου, 48.

- Lecky 1898, pp. 274–295.

- Pliny the Elder, XXXIV,17.

- Spivey 1996, pp. 114–115.

- Edmonds 1931, p. 377.

- Marm. Par. Ep. 54.70; Pausanias, 1.8.5

- Pliny the Elder, XXXIV 70.

- Arrian De Exp. Alex. III.xiv

- Worthington 2003, p. 45.

- Valerius Maximus, II.x

- Plutarch, De Adulat et Amici Discrimine

- Lycurgus, §51.

- Pliny the Elder, XXXIV ix.

- Stewart 1997, p. 73.

- British Museum: London B 605. Beazley, Attic Black-figure Vases, 411.4.

- "Ceremonial Chair (The Elgin Throne". J. Paul Getty Museum. 74.AA.12. Archived from the original on 2006-09-18.

- Smyth 1900, p. 478.

- Athenaeus, XV, 695.

- Lowth 1839.

- Larcher 1844, p. 453.

- glbtq: Harmodius and Aristogeiton Archived 2014-10-06 at the Wayback Machine

- Demosthenes & Kennedy 1856, p. 266.

- Elton 1833, pp. 885.

- Nick Fisher, Aeschines (2001). Against Timarchos. p. 27; Oxford University Press; ISBN 0198149026

- Aul. Gel. 9.2.10; Lib. Decl. 1.1.71

- Cf. Aeschines, trans. Charles Darwin Adams, (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd., 1919), [132] & [133]

- Victoria Wohl, Love among the Ruins: The Erotics of Democracy in Classical Athens p. 5

References

- Ancient histories

- Aristotle. The Constitution of the Athenians. XVIII.

- Athenaeus. The Deipnosophists. XIII, VI. 70.

- Aristotle (1952). Athenian Constitution. 18. Translated by Rackham, H. Cambridge, MA & London: Harvard University Press & William Heinemann Ltd. 1.

- Demosthenes. Against Leptines.

- Herodotus (1920). Histories. Translated by Godley, A. D. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Lycurgus. Against Leocrates.

- Pliny the Elder. Natural History. XXXIV.

- Plutarch (1878). "The Malice of Herodotus". Moralia (Complete). Translated by Goodwin, William W.

- Polyaenus. Strategies. VIII. xlv.

- Thucydides. History of the Peloponnesian War. VI. 56–59.

- Other

- Demosthenes; Kennedy, Charles Rann (1856). The Orations of Demosthenes. H.S. Bohn. p. 264.

- Edmonds, John Maxwell (1931). Lyra Graeca; Being the Remains of All the Greek Lyric Poets from Eumelus to Timotheus excepting Pindar, (3 vols). 2. London & New York: William Heinemann & G. P. Putnam's Sons. p. 377.

- Elton (1833). "The Greek Anthology". Blackwood's Magazine. William Blackwood. 33 (209): 885.

- Fabbro, Helena (1995). Carmina Convivalia Attica. Critical Edition with Translation and Commentary. Roma (publisher Istituti Editoriali e Poligrafici Internazionali) pp. 30–34, 76–77, 137–152 ISBN 88-8147-082-9

- Larcher, Pierre-Henri (1844). Larcher's Notes on Herodotus, historical and critical comments on the History of Herodotus, with a chronological table; (Translated from the French). Translated by William Desborough Cooley. p. 453. para 129.

- Lavelle, Brian M. (Autumn 1986). "The Nature of Hipparchos' Insult to Harmodios". The American Journal of Philology. 107 (3): 318–331. doi:10.2307/294689. JSTOR 294689.

- Lavelle, Brian M. (1993). The Sorrow and the Pity: A Prolegomenon to a History of Athens under the Peisistratids, c. 560–510 B.C. Historia Einzelschriften 80. Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag. ISBN 3-515-06318-8.

- Law, Randall David (2009). Terrorism: a history (illustrated ed.). Polity. p. 18. ISBN 978-0-7456-4038-9.

- Lecky, W.E.H., ed. (1898). History of European Morals. II. pp. 274–295.

- Lowth, Robert (1839) [1756]. "Lecture I. The Introduction. Of the Uses and Design of Poetry". Lectures on the Sacred Poetry of the Hebrews. Translated by Gregory G. (fourth ed.). Oxford University.

- Nagy, Gregory (1999) [1979]. "Chapter 10: Poetic Visions of Immortality for the Hero". The Best of the Achaeans Concepts of the Hero in Archaic Greek Poetry (Revised ed.). The Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Smith, William, ed. (1870). "Amphicrates". Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology. 1. p. 149.

- Smyth, Herbert Weir (1900). Greek Melic Poets. Macmillan & Co. p. 478.

- Spivey, Nigel (1996). Understanding Greek Sculpture. Thames & Hudson. pp. 114–115. ISBN 978-0500237106.

- Stewart, Andrew (1997). Art, Desire, and the Body in Ancient Greece. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 73. ISBN 978-0521456807.

- Worthington, Ian (2003). Alexander the Great: A Reader. Routledge. p. 45. ISBN 0-415-29187-9.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

External links

- Livius, Harmodius and Aristogeiton by Jona Lendering