Hattie Bartholomay

Harriet "Hattie" Eliza Ross (married names: Mansfield, Bartholomay, Bruckman) (February 4, 1875 – December 9, 1954) was an American painter and doll designer and maker known especially for her award-winning unbreakable kid doll.

Dolls

Bartholomay was nine years old when she made her first doll. Her mother, a dressmaker, provided her with the needed materials. When she had completed twelve cloth dolls she opened a pin store, putting the dolls on sale — all twelve sold on that first day. She was so successful that soon she was not only selling her dolls but dressing and repairing the dolls of other girls.[1] [2]

Bartholomay continued making dolls and as a young woman entered and won a doll contest sponsored by the Portland department store, Meier and Frank Co.[1] Her dolls were so popular among exhibition visitors that following her first showing Meier and Frank Co. commissioned her to make dolls to sell through the store.[1][3][4]

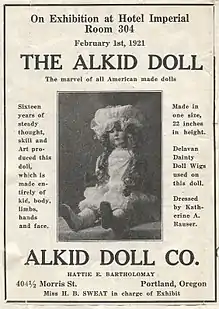

In the early part of the 20th century, nice dolls for children were often made of porcelain, and therefore breakable. Bartholomay had long dreamed of making an unbreakable doll for children that would be as beautiful as the porcelain dolls. After much experimentation she collaborated with an Italian sculptor and designed and made a doll out of kid glove which was "considered more beautiful in every way than any of the foreign toys," at the annual Toy Fair in New York City. The dolls had glass eyes, movable heads and limbs and could sit and stand on their own. They were beautiful, and nearly unbreakable. Meier and Frank Co. was delighted and the dolls were soon on their shelves and on the shelves of other department stores.[1][4][5]

_and_two_of_her_wax_dolls.jpg.webp)

During the 1920s and 1930s Bartholomay's work was exhibited at numerous doll shows where she received widespread recognition. But it was her unbreakable kid doll that garnered the most attention. In 1921 she was honored at the annual American International Toy Fair in New York.[6] The following is excerpted from an article titled, “New American Doll Outclasses Foreign Made Toys,” which ran in The New York Herald on Sunday, March 6, 1921, and describes the doll and its inception:

When [World War I] temporarily halted the pilgrimage of German and French dolls to this country, American manufacturers of toys were urged to produce dolls that would rival their foreign cousins. Mrs. Hattie E. Bartholomay of Portland, Ore., accepted the challenge and designed an adorable little creature, light enough for a child to hold, yet of a size that appeals to ninety-nine out of every hundred little girls, whose maternal joy is in proportion to the cubic inches of their pet. [The doll] is made entirely of fine kid. Its arms, legs and torso look human, which is more than can be said of some dolls. The coloring is exquisite and the apparel is such as would delight a small girl and interest the girl’s mother. For every garment is made of fine muslin or silk and is hand made. Children adore the soft, pink, chubby cheeks and the supple body. And there is no danger of breaking off an arm or a leg, for the kid body is practically everlasting. [The doll] the equal of which . . . was produced by no other person or firm in this country preceding, during or since the war, nor has it a peer across the Atlantic.[6]

Following her success at the New York Toy Fair Bartholomay’s kid dolls were sold all over the United States.[1]

While Bartholomay’s kid doll was designed to last a lifetime of play, she also made dolls for display. These dolls were made of wax and were frequently made in themed groups, as she did in a series of cowboys and cowgirls illustrative of the Pendleton, Oregon Round-Up.[2] In December 1939, she was interviewed by The Oregonian and described her doll-making process. “Models, she said, first are made of soap. Then plaster casts are made and these covered with cloth to which wax is applied. The finished wax figures then are clothed in appropriate costumes, all of which, including even the shoes, Mrs. Bartholomay herself makes.”[2]

Painting

Bartholomay began painting at age eight with a watercolor set given to her by her brother — painting became a lifelong passion and vocation.[1] As an adult she painted in oil and watercolor, displaying in Oregon galleries and winning numerous local awards. Her subjects were most often the people and places of Oregon. However, during the early 1900s, she supported herself and her two children by selling paintings done in the style of the 17th century Dutch masters to clients who wanted a “Rembrandt” in their home. In reality, her work in this genre is most reminiscent of the domestic scenes of Pieter de Hooch, the portraits of Frans Hals and the florals of Rachel Ruys.

In 1926, Sir Alexander Frederick Whyte was in Portland for a visit on his way back to England after serving five years as the president of the Indian parliament in Delhi. He bought six of Hattie's watercolors of Native Americans, two of which were given to King Edward and hung in Buckingham Palace.[7]

Personal life

She was born Harriet Eliza Ross on February 4, 1875 in Farnham, Quebec. At age six she, her siblings and parents, Seth Warner Ross and Cynthia Eliza Truax, became Oregon pioneers when they traveled across the continent and settled in Albany, Oregon.

Bartholomay married Claude Howard Mansfield in 1892. They had three children, Cynthia Estella, Alfred Lorenzo and Naomi Claudine. Bartholomay divorced Claude in 1905 and in 1912 married Joseph Henry Bartholomay. When he died in 1941 she married childhood friend Frederick A. Bruckman, inventor of the ice cream cone-making machine.[8]

Breitenbush Hot Springs

In 1904, Claude Howard Mansfield homesteaded Breitenbush Hot Springs in the Cascade mountains of central Oregon and began development of a spa.[9][10][11] Claude and Hattie’s original homestead cabin, long called Mansfield’s Cabin, stood until 2015 behind the Breitenbush Lodge until a heavy snow damaged it beyond repair.[12]

In the early 1920s, Frederick Bruckman purchased Breitenbush Hot Springs. In 1928, he sold his Portland, Oregon-based ice cream cone-making business to Nabisco. It was proceeds from Bruckman’s Real Cake Ice Cream Cone machine that allowed his son Merle to fulfill a dream of building a lodge there. The lodge was completed in the late 1920s and is still in use today. Through the years, Breitenbush was a place where Bartholomay enjoyed painting, and once, made a doll out of local clay and found materials for a blind girl who was visiting the springs with her parents. The doll was made especially with touch and texture in mind. Bartholomay said that this doll gave her more joy in making than any other.[1]

References

- Johl, Janet (Pagter), Your dolls and mine; a collectors' handbook, New York, H.L. Lindquist Publications, retrieved 8 April 2018

- “Doll Maker Wins Praise.” The Oregonian, Monday, December 18, 1939.

- “Dolls Ready To Entertain Tots At Show.” The Portland Telegram, Wednesday, October 28, 1925.

- Drama Of the Dolls.” Tacoma News Tribune, Sunday, May 7, 1972

- “Kid Doll Invention of Former Albany Woman Is Shown.” Albany Evening Herald, Wednesday, December 22, 1920.

- “New American Doll Outclasses Foreign Made Toys.” The New York Herald, Sunday, March 6, 1921.

- “Homeward Bound From India.” The Oregon Journal, Saturday, April 17, 1926.

- “The Romance of the Ice Cream Cone.” Western Confectioner, September, 1917.

- “Future Summer Resort.” The Morning Oregonian, August 6, 1901

- “A Long Trek Breitenbush Hot Springs.” States Rights Democrat, Albany, Oregon, January 23, 1891

- “Those Hot Springs.” States Rights Democrat, Albany, Oregon, May 17, 1889.

- “Famous Divorce Case Ended By Decision of Judge George.” Daily Capital Journal, Salem, Oregon, August 22, 1905.