Havana on the Hudson

Havana on the Hudson[1][2] is a nickname for the northern part of Hudson County, New Jersey, United States. The name is derived from the Cuban capital Havana and from northern Hudson County's geographic proximity to the Hudson River.

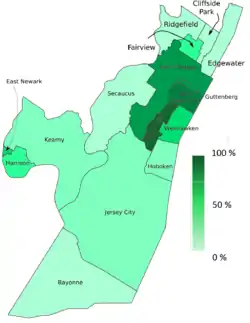

During the latter half of the 20th century, Cuban émigrés and exiles left their country and relocated to Union City, West New York, and surrounding communities in search of economic opportunity and political freedom.[3] Although the area during this period became significantly influenced by Cuban culture, over the course of the decades that followed, many Cubans spread into adjacent towns and many other Hispanic groups also moved into the area, resulting in a widespread and diverse Latino culture, commerce and identity that is non-exclusive of any people of Hispanic descent,[4][5][6][7][8] though Cubans remain a powerful voting bloc.[2][9] Numerous towns on the Hudson Palisades in northern Hudson and southeast Bergen counties have populations where more than 50% of the residents are foreign-born, often with a Hispanic majority, as well as being among those places in the United States with some of the highest population densities.[10]

Background

Prior to the Cuban Revolution, approximately 150,000 Cubans lived the United States, with concentrations in New York City and in Key West and Tampa in Florida. There was a small community of about 2,000 people living in Union City, who had originally arrived after the 1940s, many from Fomento or the semi-rural province of Villa Clara. North Hudson had urbanized and seen massive population growth in the early 20th century and was considered to be the Embroidery Capital of America, due to that and other textile industries which had been developed by the German speaking immigrants who dominated around the start of the 20th century[11][12] and were later followed by waves of Irish, Slavs, Jews, Middle Easterners and Italians. By the 1960s, North Hudson was feeling the shift in demographics as urban decline and post-war prosperity of the 1950s led to greater suburbanization in New Jersey. Relatively stable, the population was decreasing.[13] In many ways, influx of new residents led to a changing of the guard that helped save the area from the more severe downward spiral being experienced in older urban areas throughout the New York metropolitan area.[1][14]

Immigration

First wave

In the last half-century, several hundred thousand Cubans of all social classes have emigrated to the United States.[15] In the immediate aftermath of the Cuban Revolution, an initial exodus (1959–1962) of little more than 200,000 people left Cuba, where the Cuban government had begun to nationalize industry and implement Soviet-style policies. Many people headed to Miami, the American city nearest to the island. The initial wave were mostly connected to the Fulgencio Batista oligarchy who had been stripped of their property and privilege.

The convenience to New York, economic potential, family connections, the possibility of home ownership, and a chance to replant a tight-knit community may have been the initial attraction for emigres who were forced to flee. As they moved into the area, they were able to purchase homes and business from those inclined to leave for the suburbs. Hudson County was the preferred destination for many immigrants and soon became the main center for Cuban American culture. Union City had opportunities offered by the embroidery industry. According to author Lisandro Perez, Miami was not particularly attractive to Cubans prior to the 1960s.[16] A short-lived team, the Jersey City Jerseys, composed of players from the Havana Sugar Kings, made Roosevelt Stadium in Jersey City their home.

Freedom Flights

Following the Cuban Missile Crisis, then president John F. Kennedy imposed travel restrictions on February 8, 1963, and the Cuban Assets Control Regulations were issued on July 8, 1963, under the Trading with the Enemy Act in response to Cubans hosting Soviet nuclear weapons. Under these restrictions, Cuban assets in the United States were frozen and the existing restrictions were consolidated in an embargo, known as el bloqueo, Spanish for blockade. Those who wished to leave Cuba were considered refugees, and were offered alien resident status in a US sponsored resettlement program transported on what became known as Freedom Flights (1965–1974). As they were unable to take any assets or personal belongings this often was only possible for those with friends, family, or sponsors in the United States and the path to citizenship. (Children born in the USA automatically became US citizens).[17]

Immigration liberalization

Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 changed long-held immigration policies saw new immigration from non-European nations which changed the ethnic make-up of the United States.[18] Immigration doubled between 1965 and 1970, and doubled again between 1970 and 1990. The most dramatic effect was to shift immigration from Europe to Asia and Central and South America. James Hughes, a professor of urban planning at Rutgers University, was quoted in The New York Times as saying that changes made to immigration laws in 1964 were responsible for much of the influx of Hispanic immigrants to the county.[19]

Marielitos

The Mariel boatlift was a mass exodus of Cubans who departed from Cuba's Mariel Harbor for the United States between April 15 and October 31, 1980. Some of these refugees, who had departed on makeshift boats and rafts recovered by the Coast Guard eventually made it to North Hudson.[20] On September 9, 1994, the U.S. and Cuban governments agreed to a Quota system in which the American government would grant at least 20,000 visas annually in exchange for Cuba’s pledge to prevent further unlawful departures by rafters.[21]

Political affiliation

Anti-Castro sentiment

During the 1970s and 1980s, Jose Miguel Battle, Sr. (c. 1930–2007), a Bay of Pigs Invasion operative who became known as "Godfather of the Cuban mafia", for many years operated in Hudson County.[22][23] Omega 7, a paramilitary group dedicated to Castro's overthrow, had membership and operations in Hudson County.[24] Other para-military groups also operated in the area.[25]

Cuban Americans and immigrants have traditionally been part of the Cuban dissident movement (anti-Castro as opposed to anti-Cuba) which has greatly influenced their political affiliation. New Jersey's 13th and 9th congressional districts, traditionally democratic strongholds, elections have been influenced by candidates willingness to support sanctions against the Castro regime. It is not uncommon for local candidates to campaign in South Florida to garner support for their position, or to vote Republican Party candidates who support their view on the issue.

The Cuban Democracy Act was a bill presented by U.S. Congressman Robert Torricelli (D-NJ 9th CD and passed in 1992 which prohibited foreign-based subsidiaries of U.S. companies from trading with Cuba, travel to Cuba by U.S. citizens, and family remittances to Cuba. The act was passed as “A bill to promote a peaceful transition to democracy in Cuba through the application of sanctions directed at the Castro government and support for the Cuban people.” The act stated that “[t]he government of Fidel Castro has demonstrated consistent disregard for internationally accepted standards of human rights and for democratic values” adding “[t]here is no sign that the Castro regime is prepared to make any significant concessions to democracy or to undertake any form of democratic opening.”[26][27]

The Helms-Burton Act (1996) further restricted interaction with Cuba, but effective May 10, 1999, with CFR Title 31 Part 515, was amended.[28] Presidents Bill Clinton and George W. Bush both signed a provision allowing for a waiver of the law. In April 2009 a ban on travel and the sending of money and medicine to Cuba was lifted by Barack Obama.[29][30][31]

Changing policy and attitudes

Support for the United States embargo against Cuba (aka el bloqueo, or "the blockade") was a stance held for many years, particularly exiles, and less so by their children. There still remains resistance to normalization of relations with or support of the Cuban government. At the 2009 opening of the Union City High School, a band that had played in a peace concert in Havana was scratched from the program.[32] and rallies against it are still organized.[33][34] At the same time, while Hispanics have become the largest minority in the United States, often they do not present a solid front. Younger generations can often hold differing opinions than their earlier immigrant counterparts.[4]

Cultural impact

Public office

To vote and hold public office in the United States one must be a U.S. citizen. The lower Hudson Palisades region has become one of the parts of the country with the highest rates of foreign-born residents.[10] Nonetheless there are several politicians of Latin American ancestry, some born abroad and some born locally, who have been elected to political office.[4][26] William Musto, who served two terms as mayor of Union City, from 1962 to 1970, and from 1974 to 1982 was described by The New York Times was "a pioneer in affirmative action" for being one of the first mayors in the state to hire and promote Hispanic residents and push for bilingual education.[35] Notable public officials from the Latino community include:

- Marlene Caride

- Zulima Farber, judge

- Bob Menendez, United States Senator[36][37]

- Vincent Prieto, State Assemblyman 32nd legislative district

- Ruben J. Ramos, State Assemblyman, 33rd legislative district

- Eliu Rivera, Freeholder[38] District 4

- Caridad Rodriguez, State Assemblywoman 33rd Legislative District[39]

- Felix Roque, Mayor of West New York

- Esther Salas, federal district judge for the United States District Court for the District of New Jersey

- Albio Sires, Member of the United States House of Representatives 8th congressional district

- Anthony R. Suarez, served as Mayor of Ridgefield, New Jersey[40]

- Silverio Vega, Mayor of West New York. Formerly State Assemblyman 33rd legislative district[41] and Freeholder District 7

Streetscape

The Latino presence along the Hudson is most visible and palpably felt along Bergenline Avenue which runs for 90 block through North Hudson[42][43] and continues north as Anderson Avenue into Fairview. It is along this corridor that many privately operated hail and ride minibuses, or guaguas (as called in some Caribbean countries) travel to points in Jersey City and Manhattan. Others operated by Spanish Transportation also run along the marginal road of the Lincoln Tunnel Approach and Helix between 42nd Street and Paterson, another city with a high immigrant population.[44][45][46]

Summit Avenue near the Transfer Station is also home to a concentration of Latino businesses, as are sections of Palisade Avenue in Jersey City Heights. Marin Boulevard in Downtown Jersey City was named to honor of Luis Muñoz Marín and the large Puerto Rican population living in the neighborhood. Signage and the language are bilingual in North Hudson. While it is not uncommon to see franchised chain stores, there are still many family-run businesses throughout the area, and some mom and pop operations. Throughout the neighborhoods corner stores and bodegas are commonly found stocked with Goya Foods, the largest Hispanic-owned food company in the United States,[47] which is headquartered in nearby Secaucus.

The area offers a variety of Latin American cuisines, including Cuba,[48] Ecuadorian and Puerto Rican, Mexican including trans-Latino tostones, ropa vieja, batidos, and the like.[42][49] Local, traditionally made Cuban cigars, are to be found.[50][51][52][53][54]

Annual events

The Cuban Day Parade of New Jersey, since its inception at the millennium, has run south along Bergenline Avenue in North Hudson County, and grown to be the centerpiece of large festivities which have taken place at Scheutzen Park and Celia Cruz Park.[55][56][57][58][59][60] The latter is the centerpiece what has been called the "Walk of Fame". Dedicated to the then deceased salsa singer Celia Cruz in ceremonies attended by her husband Pedro Knight in 2004,[61] the homage has grown to include marble stars honoring musicians and singers Tito Puente, Johnny Pacheco, Israel "Cachao" Lopez, Beny Moré, La India, and news anchor Rafael Pineda.[62]

The longest running passion play in the United States has been performed at Union City's Park Performing Arts Center since 1931.[63][64] In 1997, there was a minor controversy when an African-American actor was cast as Jesus.[65][66] Three Kings Day, and important holiday in the Hispanic community, is celebrated there annually since the 1980s.[67][68][69][70] The peninsular city of Bayonne, NJ is also home to an annual Hispanic Day Parade which marches through a large Latinized section of the city.

Media

El Especial and El Especialito, Spanish-language weeklies targeting audiences in New Jersey, New York City and Miami is based in Union City[71] with a circulation in the New York metropolitan area of about 230,000.[72][73] Before its closure in 1991 the Hudson Dispatch included pages in Spanish, as did the Jersey Journal.[74] Since May 2010, a free bilingual newspaper Hudson Dispatch Weekly has served the North Hudson area. Published by the Evening Journal Association, at 30 Journal Square, one side is printed in English, and the other in Spanish under the title la comunidad.[75][76] The Brooklyn-based daily, El Diario La Prensa, printed in Bogota, New Jersey is widely available.

The Spanish Broadcasting System was founded in Newark, New Jersey in 1983, by emigre Pablo Raúl Alarcón, Sr. and Raúl Alarcón, Jr.,[77] and operates Paterson-licensed WPAT. Univision WFUT and Telefutura's WXTV, a duopoly in the New York metropolitan area media market are licensed to and have their studios in northeastern New Jersey. WNJU, the flagship station of the Spanish-language Telemundo television network, is licensed to Linden and has its studios and offices in Fort Lee.

Arts

North Hudson is sometimes called NoHu in the visual arts community.[78] Among those visual and performing artists and producers with a Latino background originating or living in the region are:

- Bobby Cannavale (born 1971), actor known for his roles on Ally McBeal, Third Watch, and Will & Grace.[79]

- Joey Diaz, comedian and actor

- Paquito D'Rivera, nine-time Grammy Award–winning jazz maestro and writer[80]

- Henry Escalante, pop musician, and one of the 15 finalists from the 2007 season of the MTV reality show Making Menudo.[81]

- Julio Fernández

- Lucio Fernandez

- Daisy Fuentes

- Erick Morillo (born 1971), DJ and music producer[82]

- Luis Moro (born 1964), actor, filmmaker, writer, best known for his history making-film Love and Suicide, which made him the first American to break the embargo on Cuba to film a feature there.[83]

- Oscar Nunez, screenwriter/actor[84]

- Carol-Lynn Parente, executive producer of Sesame Street, (Puerto Rican-American)[85]

- Franck de Las Mercedes, folklore artist (Nicaraguan American)[86]

- Caitlin Sanchez, actress[87]

- Discuba, a record label

See also

- Cuban Americans

- Hispanics and Latinos in New Jersey

- Alvaro de Molina

- Ironbound, a Portuguese and Brazilian enclave in Newark across the Passaic River from Harrison and Kearny

- Little Havana, Miami, Florida, Havana on the Hudson's sister city[88]

- India Square, an Indian enclave in Jersey City

- Five Corners, a Filipino shopping district in Jersey City

- La Ventiuno, Paterson

- Little Lima

- Koreatown, Palisades Park, a Korean enclave in southeast Bergen County

- Hudson Waterfront, sometimes called Gold Coast (New Jersey)

- Gateway Region, a name for northeastern New Jersey

References

- Bartlett, Kay (June 28, 1977), "Little Havana on the Hudson", Pittsburgh Post-Gazette

- Mohka, Kavita (September 3, 2011), "Beyond Havana in Union City", Wall Street Journal, retrieved 2011-12-06

- "Havana on the Hudson". 20 October 2012.

- Jennemann (July 3, 2003), Latinos have the numbers Progressing towards more power in political arena, retrieved 2011-12-14

- Nieves, Evelyn (November 30, 1992). "Union City and Miami: A Sisterhood Born of Cuban Roots". New York Times. Retrieved 2010-05-27.

- Padilla, Felix; Kanellos, Nicolas (June 1994), Handbook of Hispanic Cultures in the United States: Sociology, Arte Publico Press, ISBN 1558851011

- Marifeli Perez-Stable. "That other Cuban community". The Miami Herald. December 3, 2009.

- Rosero, Jessica. "Most liquor licenses? Bumpiest town? Local municipalities hold unusual distinctions" Archived 2008-05-28 at the Wayback Machine, Hudson Reporter, August 27, 2006. Accessed June 25, 2007. "At one time, Union City had its own claim to fame as being the second largest Cuban community in the nation, after Miami. During the wave of immigrant exiles of the 1960s, the Cuban population that did not settle in Miami's Little Havana found its way to the north in Union City. However, throughout the years, the growing Cuban community has spread out to other regions of North Hudson."

- Havana USA: Cuban Exiles and Cuban Americans in South Florida, 1959-1994 By María Cristina García

- Roberts, Sam (December 14, 2010), "Region Reshaped as Immigrants Move to Suburbs", The New York Times, retrieved 2011-12-06

- "The Schiffli Embroidery and Lace Association". www.schiffli.org.

- Cheslow, Jerry (February 11, 2001), "If You're Thinking of Living In/Union City, N.J.; Manhattan Views At Blue-Collar Price", The New York Times, retrieved 2011-12-06

- New Jersey Resident Population by Municipality: 1930 - 1990 Archived 2015-05-10 at the Wayback Machine, New Jersey Department of Labor and Workforce Development. Accessed February 18, 2015.

- Trillin, Calvin (June 30, 1975). "Observations while Eating Carne Asada on Bergenline Avenue". The New Yorker. Retrieved 2011-01-27.

- Pedraza, Silvia (2007). Political disaffection in Cuba's revolution and exodus. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. p. 5. ISBN 9780521867870. Retrieved 2009-09-14.

- Grenier, Guillermo J; Stepick III, Alex (1992), Miami Now!: Immigration, Ethnicity, and Social Change, University Press of Florida, p. 232, ISBN 978-0-8130-1154-7

- "Miami Herald database tracks those who came on Freedom Flights". Miami Herald. December 16, 2008.

- Peter S. Canellos (November 11, 2008). Obama victory took root in Kennedy-inspired Immigration Act. The Boston Globe. Retrieved 2008-11-14.(subscription required)

- Gray, Jerry (February 23, 1991). "Hudson County a Harbinger of a New Hispanic Influence". The New York Times. Retrieved April 5, 2010.

- "Nation: Happy to Wash Dishes". TIME. 1980-05-19. Retrieved 2012-03-18.

- "CUBA: U.S. Response to the 1994 Cuban Migration Crisis" (PDF). U.S. General Accounting Office. September 1995. Retrieved 2009-09-14.

- Buder, Leonard. "11 Are Accused in Fatal Blazes at Betting Sites", The New York Times, October 8, 1985. Accessed January 5, 2008. "A former resident of Union City, N.J., Mr. Battle now lives in Miami."

- Rosero, Jessica; "Death of a legend: North Hudson's Cuban Godfather dead at 77"; Union City Reporter; August 12, 2007; Pages 3 & 6.

- McFadden, Robert D. (November 26, 1979), "Cuban Refugee Leader Slain in Union City", The New York Times, p. B-2

- "An Army in Exile Cuban Terrorists Four Miles from Manhattan". New York Magazine. September 10, 1979. Retrieved 2014-06-28.

- Gray, Jerry (February 23, 1991). "Hudson County a Harbinger of a New Hispanic Influence". New York Times. Retrieved 2010-06-06.

- Bishin, Benjamin G. (2004). "Tyranny of the Minority: The Subconstituency Politics Theory of Representation" (PDF). Latin American Work Group. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-03-27. Retrieved 2010-05-30. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Cuba and the Helms-Burton Act Archived 2000-08-19 at the Wayback Machine

- Rispoli, Michael (April 13, 2009), Cubans in N.J. respond to lifting of travel ban, Newark: The Star-Ledger

- Cave, Damien (April 8, 2009), "Exiles Want to Expand U.S.-Cuba Relations", The New York Times

- Hackjournal, Charles (April 14, 2009). "Cubans Here: TIME TO SAY ADIÓS TO POLICY Restrictions not working, but openness may, they say". Jersey Journal.

- Torres, Agustin C. (September 25, 2009), "Union City cancels band appearance after group plays in Havana", The Jersey Journal

- North Jersey Cuban exiles prepare for weekend march – April 19, 2010

- Hope, Bradley (August 2, 2006). "Havana on Hudson Reverberates After Castro's Operation", The New York Sun. Accessed June 25, 2007. "Several of the group's leaders sat in chairs around the union hall on a quiet street in Union City, N.J., a town minutes away from Manhattan that was once known as "Havana on the Hudson".

- Gettleman, Jeffrey (March 1, 2006). "William Musto, 88, a Mayor Re-elected on His Way to Jail". The New York Times. Retrieved April 4, 2010.

- "Robert Menendez, a Politician Even at 20" The New York Times, December 10, 2005

- Wayne Parry, Associated Press (via the San Francisco Chronicle), Menendez Inspires Pride in Cuban-Americans, December 8, 2005

- "María DeCastro Blake Community Service Award 2007 Honoree". The Newark Public Library. 2007. Archived from the original on July 16, 2011. Retrieved April 5, 2010.

- "Candidates for November 3, 2009 General Election". Hudson County Clerk. Archived from the original on July 18, 2011. Retrieved April 5, 2010.

- Llorente, Elizabeth (October 7, 2013). "In One New Jersey Town, Latinos Dominate Council, Bucking National Trend". Fox News Latino. Retrieved 2013-11-11.

- Assemblyman Vega's Legislative Website Archived 2012-05-31 at the Wayback Machine, New Jersey Legislature. Accessed January 12, 2008.

- Ferretti, Fred (December 30, 1981). "New York, New Year, Old Delights". The New York Times: C1.

- McLane, Daisann (December 11, 1991). "Along 90 Blocks of New Jersey, A New World of Latin Tastes". The New York Times.

- "Breve Historia del Castellano o Español". Etimologias.dechile.net. Retrieved 2012-03-18.

- Česky. "Autobús - Wikipedia, la enciclopedia libre" (in Spanish). Es.wikipedia.org. Retrieved 2012-03-18.

- Hudson County Bus Circulation and Infrastructure

- "First Lady Michelle Obama joins Goya Foods in announcing "Mi Plato" Resources for families | The White House". Whitehouse.gov. 2012-01-26. Retrieved 2012-03-18.

- Mokha, Kavita (September 3, 2010). "Beyond Havana, in Union City". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on January 15, 2019. Retrieved April 3, 2019.

- "Union City/North Bergen". Eating In Translation. Retrieved 2012-03-18.

- "Smoke signals Local cigar shop owner sheds light on the other side of tobacco". Hudson Reporter. Retrieved 2012-03-18.

- "The Wide World of Cigars Union City NJ - Union City NJ, cigar retailing shops, Union City NJ how to find the finest cigars, Union City NJ tips for finding the finest cigars, Union City NJ advice on finding the finest cigars, Union City NJ suggestion to finding the finest cigars". Articles.directorym.com. Archived from the original on 2012-03-08. Retrieved 2012-03-18.

- "North Jersey cigar maker has a starring roll". NorthJersey.com. 2010-12-14. Retrieved 2012-03-18.

- "JERSEY; When a Good Cigar Is More Than a Smoke - New York Times". Nytimes.com. 1995-06-11. Retrieved 2012-03-18.

- "Small Biz Spotlight This is Heaven Take a puff of a hand rolled cigar at Rodriguez Puro Cigars in The Heights". Hudson Reporter. 2007-10-14. Retrieved 2012-03-18.

- "At Parade, Immigrants Bask in El Duque's Glory - New York Times". Nytimes.com. 1998-10-28. Retrieved 2012-03-18.

- Rosero, Jessica (June 11, 2004). "Celebrating Cuba Pride: Fifth annual Cuban Day Parade draws residents and honored guest". The Hudson Reporter. Archived from the original on July 6, 2017. Retrieved 2010-06-15.

- Miller, Jonathon (May 31, 2007). "Judge Decides Against a Mayor Who Banned Cuban Parade". The New York Times. Retrieved 2010-06-15.

- "Website Cuban Day Parade and Festival of New Jersey". Archived from the original on 2012-03-21. Retrieved 2012-03-18.

- Schmidt, Margaret (May 30, 2009). "Cuban Parade of New Jersey". Jersey Journal. Retrieved 2010-06-15.

- Rosero, Jessica. "The parade marches on Eighth annual Cuban Day Parade of New Jersey keeps traditional route". The Hudson Reporter. Archived from the original on 2015-09-24. Retrieved 2010-06-15.

- "Homage to Celia Cruz: UC to pay tribute to Queen of Salsa with events, park dedication". Archived 2007-09-30 at the Wayback Machine, Union City Reporter, May 30, 2004.

- Fernandez; 2010; Page 74.

- Jay Romano. "Union City Journal; 2 Passion Plays Thrive On a 'Friendly Rivalry'" The New York Times March 5, 1989

- "Passion Play at Park Performing Arts Center". Archived from the original on 2011-07-27. Retrieved 2012-03-18.

- Briggs, David; "'I was looking at him and I couldn't see color'" Archived 2007-11-09 at the Wayback Machine

- "Stories on the Passion Play controversy at passionplayusa.net". Archived from the original on 2008-05-13. Retrieved 2012-03-18.

- "Three Kings Day show, toy giveaway tomorrow in Union City". NJ.com. 2010-01-09. Retrieved 2012-03-18.

- "Three Kings Day celebration in Union City". Jersey Journal. January 6, 2010. Retrieved 2010-12-01.

- "Three Kings Day celebration in Union City". nj.com. January 6, 2010. Archived from the original on July 14, 2011. Retrieved 2010-12-01.

- "Events". National Association of Cuban Women. Archived from the original on 2012-03-15.

- "We make the difference ! 12 editions in all of New York, New Jersey and Miami... in less than 25 years!!!". Elespecial.com. Archived from the original on 2012-03-19. Retrieved 2012-03-18.

- "Distributions". Elespecial.com. Archived from the original on 2012-03-21. Retrieved 2012-03-18.

- El Especial's official website

- The Jersey Journal. "Jersey Journal parent company warns employees of possible closure; publisher optimistic paper can be saved". NJ.com. Retrieved 2012-03-18.

- "Notices (colofon)". Hudson Dispatch Weekly. Jersey City: Evening Journal Association. 2010-12-18.

- The main cover story of the May 13, 2010 edition is mirrored here on NJ.com.

- "Pablo Raúl Alarcón, Sr." Archived 2012-03-20 at the Wayback Machine, Spanish Broadcasting System, accessed 2012-03-03.

- Paul, Mary; and Matzner, Caren. "Scores of artists find a place in N. Hudson WNY, Union City, Weehawken, and North Bergen becoming 'NoHu'" Archived 2013-05-11 at the Wayback Machine, The Union City Reporter, April 17, 2008, pages 1, 6 and 19. Accessed January 14, 2012.

- Hernandez, Ernio; "Upcoming Hurlyburly Star Inks Deal for New NBC "French Connection" Drama"; Playbill, December 23, 2004. Archived November 11, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- "Paquito D'Rivera at NJPAC". NJ.com. Retrieved 2012-03-18.

- Hague, Jim; "A teen Latin pop star" Archived 2012-02-27 at the Wayback Machine Union City Reporter, November 11, 2007.

- 1989 Altruist: A Classic Year The Emerson High School yearbook for 1989

- Rosero, Jessica. "The revolution begins within: Hudson County native brings his Cuban people back home" Archived 2012-02-27 at the Wayback Machine, Union City Reporter, May 28, 2006. Accessed June 10, 2010.

- "'Office' worker Nunez has a second 'Home'", New York Daily News, May 9, 2007. Retrieved 2011-12-06

- Rohan, Virginia. "Former fan now in charge of 'Sesame Street'", The Record (Bergen County), August 13, 2007. Accessed August 13, 2007.

- Levine, Daniel Rome. "Triunfador Franck de Las Mercedes", ABC News, August 16, 2007. Accessed August 18, 2008. "Standing in the middle of his one-bedroom loft apartment in an industrial part of Weehawken, N.J., the 34-year-old abstract painter covers a small brown cardboard box in white acrylic paint and then carefully drips red and hot pink paint on it."

- "La nueva voz de "Dora, la exploradora" la hace una niña cubano-estadounidense", Terra Networks, December 4, 2008. Accessed December 30, 2010.

- Prieto, Yolanda (2009-05-28). The Cubans of Union City: immigrants and exiles in a New Jersey community - Yolanda Prieto - Google Boeken. ISBN 9781439903445. Retrieved 2012-03-18.

External links

- Miami Herald-50 Years

- City data: US cities with highest percentage of persons born in Cuban

- Lebiednik, Dan (2013). "Havana on the Hudson Where have Union City's Cubans gone?". Shoe Leather Magazine. Archived from the original on 2013-12-03. Retrieved 2013-11-24.

- Mixed reaction from Cuban-Americans in North Jersey on improving relations with Cuba

- Obama's Cuba Announcement Continues to Send Ripples Through New Jersey

- Why N.J. Cuban-Americans Menendez & Sires detest Obama's Cuba policy