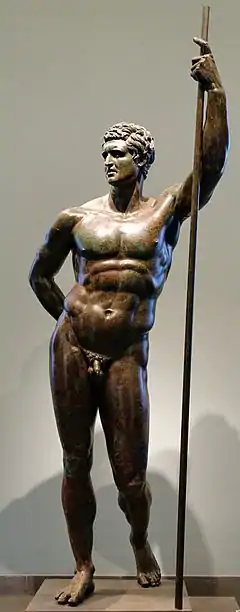

Hellenistic Prince

The Hellenistic Prince (or the Seleucid Prince) is a Greek bronze statue made in the 2nd century BC, now in the collections of the Palazzo Massimo alle Terme in Rome. It was found in 1885, together with the Boxer at Rest, on the Quirinal Hill, probably near the Baths of Constantine during the construction of the National Theatre. The two statues were however not part of an ensemble, being of different dates. There are significant debates on who is the person pictured, the original attribution to a Hellenistic prince being now rejected in favour of a Roman general—possibly Scipio Aemilianus, although there have been other suggestions.

| The Seleucid Prince | |

|---|---|

| The Hellenistic Prince, Statue of Attalus II | |

| |

| Year | 2nd century BC |

| Medium | Bronze statue |

| Location | Palazzo Massimo alle Terme, Rome, Italy |

Description

The statue was cast using a lost wax process. The eyes were put in their sockets later, but are now lost.

It represents a naked young man with a light beard, reclining on a spear in an heroic pose, which is taken from Lysippos' Heracles. The first studies of the statue described it as an Hellenistic prince, Seleucid or Attalid (specifically Attalus II), but this attribution has been rejected. Since there is no consensus on the character's identity, the original name still stands.

Indeed, scholars now mostly think the man is actually a Roman general, portrayed by a Greek artist working in Rome. Opinions on the character pictured widely differ: Lehman thinks it is Quintus Caecilius Metellus Macedonicus; Balty and Croz recognise Titus Quinctius Flamininus; Papini suggests Gnaeus Manlius Vulso; finally, Coarelli and Etcheto favour Scipio Aemilianus, because the statue was found near the place where he had his villa.[1]

A reconstruction project executed by the Frankfurt Liebieghaus Polychromy Research Project and headed by Vinzenz Brinkmann follows the interpretation of Otto Rossbach (1898) and Phyllis L. Williams (1945) and identifies the statue as one of the Dioscures.[2]

References

- Etcheto, Les Scipions, pp. 278-282, with a detailed historiograhical summary.

- Vinzenz Brinkmann: Die sogenannten Quirinalsbronzen und der Faustkampf von Amykos mit dem Argonauten Polydeukes. Ein archäologisches Experiment. In: Vinzenz Brinkmann (ed.): Medeas Liebe und die Jagd nach dem Goldenen Vlies. Exhibition catalogue Liebieghaus Skulpturensammlung, Frankfurt 2018. Hirmer, Munich 2018, p. 80-97.

Bibliography

- Jean Ch. Balty, "La statue de bronze de T. Quinctius Flamininus ad Apollinis in circo", Mélanges de l'école française de Rome, n°90-2, 1978, pp. 669–686.

- Filippo Coarelli, "La doppia tradizione sulla morte di Romolo e gli auguracula dell'Arx e del Quirinale", Gli Etruschi e Roma: atti dell'incontro di studio in onore di Massimo Pallottino, Rome, 1981, pp. 173–188.

- Jean-François Croz, Les portraits sculptés de Romains en Grèce et en Italie de Cynoscéphales à Actium (197-31 av. J.C.). Essai sur les perspectives idéologiques de l’art du portrait, Paris, 2002.

- Henri Etcheto, Les Scipions. Famille et pouvoir à Rome à l’époque républicaine, Bordeaux, Ausonius Éditions, 2012.

- Andreas Linfert, Bärtige Herrscher, "Jahrbuch des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts", XCI, 1976 (sur Google Books).

- Nikolaus Himmelmann, Herrscher und Athlet. Die Bronzen vom Quirinal, Milan, 1988.

- Detlev Kreikenbom, Griechische und römische Kolossalporträts bis zum späten ersten Jahrhundert nach Christus, Berlin, 1992. ISBN 978-3-11-013253-3

- Stefan Lehmann, "Der Thermenherrscher und die Fußspuren der Attaliden. Zur olympischen Statuenbasis des Q. Caec. Metellus Macedonicus", Nürnberger Blätter zur Archäologie, XIII, 1997, pp. 107–130.

- Massimiliano Papini, "Il Principe delle Terme, "Grieche oder Römer?", Bullettino della Commissione Archeologica Comunale di Roma, Vol. 103 (2002), pp. 9–42.

- Ulrich Sinn, Einführung in die klassische Archäologie, Beck, Munich, 2000, ISBN 978-3-406-45401-1, pp. 134–139.

- Ulrich-Walter Gans, Attalidische Herrscherbildnisse. Studien zur hellenistischen Porträtplastik Pergamons, Wiesbaden, 2006.