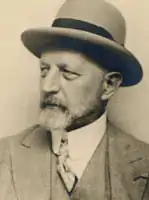

Henri Sauvage

Henri Sauvage (May 10, 1873 in Rouen – March 21, 1932 in Paris), was a French architect and designer in the early 20th century. He was one of the most important architects in the French Art nouveau movement, Art Deco, and the beginning of architectural modernism. He was also a pioneer in the construction of public housing buildings in Paris. His major works include the art nouveau Villa Majorelle in Nancy, France and the art-deco building of the La Samaritaine department store in Paris.

Henri Sauvage | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | May 10, 1873 |

| Died | March 21, 1932 (aged 58) |

| Nationality | French |

| Alma mater | École nationale supérieure des beaux-arts |

| Occupation | Architect |

| Awards | Chevalier de la Légion d'honneur |

| Buildings | La Samaritaine, Villa Majorelle |

Training and early career

Henri Sauvage studied architecture at the École nationale supérieure des beaux-arts from 1892 to 1903, in the course taught by Jean-Louis Pascal, but quit the school before receiving a diploma, and described himself as self-taught in architecture. He associated with and became friends with many leading figures in the new movements in architecture and the decorative arts, including the rationalist architect Frantz Jourdain (1847-1935), the furniture designer Louis Majorelle (1859-1926), the painter and furniture designer Francis Jourdain (the son of Frantz Jourdain), the architects Hector Guimard and Auguste Perret.

Sauvage first achieved recognition designing decoration in the Art Nouveau style. In about 1895, he designed a shop for the interior decoration and wallpaper firm of his father, Henri-Albert Sauvage, and his partner Alexandre-Amédée Jolly, which was located at 3 rue de Rohan in the 1st arrondissement (later demolished). The firm of Jolly and Sauvage received many commissions for wallpaper from Art Nouveau architects; it made the wallpaper for Hector Guimard's first Art Nouveau building, the Castel Béranger.[1] Working with his father's firm, he made stencils, then furniture and other decorative objects, working with Louis Majorelle.

Art Nouveau

Private dining room at the Café de Paris, now in the Carnavalet Museum (1899)

Private dining room at the Café de Paris, now in the Carnavalet Museum (1899)

Ceramic decoration on facade of Villa Majorelle

Ceramic decoration on facade of Villa Majorelle

En 1897, Sauvage went to Brussels, where he worked with architect Paul Saintenoy, one of the pioneers of the Art Nouveau. He also saw and studied the work of the rationalist architect Paul Hankar. The time Sauvage spent in Brussels changed his ideas about architecture, in the same way that, two years earlier, Hector Guimard had been inspired by the Art Nouveau Hotel Tassel designed by Victor Horta in Brussels.[2] In 1898 Sauvage married Marie-Louise Carpenter, the daughter of furniture designer and sculptor Alexandre Charpentier.[3] In the same year, along with Charles Sarazin, he founded his own architectural firm and became a member of the Société nationale des beaux-arts, where he regularly exhibited his decorative works.

In 1898, he received a commission from the furniture designer Louis Majorelle to construct an Art Nouveau villa in the city of Nancy, located close to the new furniture workshops Majorelle was building. Finished in 1902, the Villa Majorelle brought international attention to the young architect.[4] In 1899, Savage created two Art Nouveau private dining rooms for the celebrated restaurant Café de Paris, after the three salons that Majorelle had created the previous year. The restaurant was later demolished, but the mauve salon was recreated in the Carnavalet Museum of the history of Paris.

At the Paris Universal Exposition of 1900, Sauvage designed a theater for the American dancer Loïe Fuller, working in collaboration Pierre Roche, Francis Jourdain and the ceramic artist Alexandre Bigot; a theater called le Guignol parisien; the exhibition stand for the firm of his father, Jolly fils et Sauvage; a power generating station which produced electricity for the exhibition, as well as Art Nouveau entrances for the Exposition of the Street organized by Frantz Jourdain. He also made several projects, not realized, for a buffet, decorative masts; a pavilion for the firm of Louis Majorelle, and another for the magazine La mode pratique[5]

Low-cost housing and a shopping gallery

Low-cost apartment building at 7 rue Trétaigne 18th arrondissement, (1903-1904)

Low-cost apartment building at 7 rue Trétaigne 18th arrondissement, (1903-1904) Doorway of 7 rue Trétaigne

Doorway of 7 rue Trétaigne facade of 7 rue Trétaigne

facade of 7 rue Trétaigne Cité de l'Argentine, 111 Avenue Victor Hugo, combining apartments and a shopping gallery (1911)

Cité de l'Argentine, 111 Avenue Victor Hugo, combining apartments and a shopping gallery (1911) The Cité de l'Argentine, 111 Avenue Victor Hugo, 16th arrondissement (1911)

The Cité de l'Argentine, 111 Avenue Victor Hugo, 16th arrondissement (1911)

In 1903, he made his first venture into designing lost-cost apartment buildings and public housing. He and Sarazin founded a company, Société anonyme de logements hygiéniques à bon marché (The company for hygienic and low-cost housing). The collaboration lasted until 1916.[6] He designed and built six buildings for the company. The most notable are at 7 rue de Trétaigne, in the 18th arrondissement, built in 1903-04, and at 163 Boulevard de l'Hôpital, in the 13th arrondissement, built in 1908. Both buildings have a framework of reinforced concrete, which is clearly expressed on the outside; the spaces on the facade between the concrete frames filled with brick rue de Trétaigne, and with sandstone on Boulevard de l'Hôpital.

In addition to these two buildings created by his company, he also designed and built several HBMs, or Habitations à bon marché, which used less-expensive building materials. These are found at 20 rue Severo in the 14th arrondissement, (1905). 1 rue de la Chine in the 20th arrondissement (1907), 1 rue Ferdinand-Flocon in the 18th arrondissement Paris (1912), and one in the port city of Le Havre, at 26 rue Jean-Macé (1911). In all of these buildings he followed the principles of rational and hygienic design which had been expressed in the writings of Eugène Viollet-le-Duc. Sauvage and his contemporary Auguste Perret Sauvage were the first architects in France to use reinforced concrete in residential buildings, not simply as a means of construction, but for its architectural effect. The resulting buildings, especially the building at 7 rue de Trétaigne, were more austere than earlier buildings, but by their simplicity and functionality and modularity they created a powerful monumental effect. This style was soon used by other architects designing HBMs in Paris.[7]

In 1911, Sauvage and Sarazin constructed a new apartment building in the 16th arrondissement which had a novel feature on its ground floor; an iron and glass shopping gallery, the Cité d'Argentine, an updated version of the Passages of the late 18th and early 19th century.

The stepped apartment building

Apartment building at 26 rue Vavin, 6th arrondissement, Paris, (1912-1914)

Apartment building at 26 rue Vavin, 6th arrondissement, Paris, (1912-1914) Detail of 26 rue Vavin

Detail of 26 rue Vavin apartment building and public swimming pool at 13 rue des des amiraux, 18th arrondissement, Paris (1922-1927)

apartment building and public swimming pool at 13 rue des des amiraux, 18th arrondissement, Paris (1922-1927) Swimming pool entrance of 13 rue des amiraux (1922-1927)

Swimming pool entrance of 13 rue des amiraux (1922-1927)

After long study on ways to provide more light and air to apartment buildings, in the course of building low-income housing projects, Sauvage invented an innovative approach to the problem; beginning in 1909 he began designing buildings where the higher floors were like steps, each one set back, giving space for a terrace. He and his partner Charles Sarazin patented the idea in 1912.[8] However, he only applied the system in two buildings; at 26 rue Vavin in the 6th arrondissement, and in an apartment building at 13 rue des Amiraux. (1913-1930). The exteriors of both buildings were completely covered with white ceramic tiles made by the enterprise of Hippolyte Boulenger and company. A third stepped building for an HBM was proposed for the butte of Montmartre, but was abandoned.

The stepped buildings were exceptionally modern in concept, reduced crowding, created space, and allowed tenants to have their own gardens; the gleaming white ceramic tile gave the buildings a clean and modern appearance. These ideas later earned Sauvage credit from the architectural critic H.R. Hitchcock as one of the pioneers of modernist architecture.[9] However, because of the terraces, they gave up a large amount of rentable space both on the exterior and in the interior, where no windows were possible, and were not considered economically profitable. Sauvage had hoped that, with his new design, higher buildings might be permitted, but the city refused to alter height limitations. Sauvage solved the problem of filling the interior space by putting his own office inside the building on rue Vavin, and a municipal swimming pool inside the building on rue des Amiraux.[10] Though few stepped buildings were built during Sauvage's lifetime, they had an important impact on Paris architects between 1950 and 1980, the designs of buildings in Paris between 1950 and 1980, including Georges Candilis, Jean Balladur, Michel Andrault, Pierre Parat, and Jean Renaudie, who used similar designs in much larger buildings.

Art Deco

The Majorelle building, at 126 rue de Provence (8th arrondissement), built for Louis Majorelle (1912-1914)

The Majorelle building, at 126 rue de Provence (8th arrondissement), built for Louis Majorelle (1912-1914) MK2 Gambetta Cinema at 4 rue Belgrand, 20th arrondissement, Paris (1920).

MK2 Gambetta Cinema at 4 rue Belgrand, 20th arrondissement, Paris (1920). Studio building, 65 rue Jean de la Fontaine, 16th arrondissement, Paris, (1926–28)

Studio building, 65 rue Jean de la Fontaine, 16th arrondissement, Paris, (1926–28) Vert Galant, an art deco apartment building at 42 quai des Orfèvres, Paris, next to Place Dauphine and the Palais de Justice (1929-1932)

Vert Galant, an art deco apartment building at 42 quai des Orfèvres, Paris, next to Place Dauphine and the Palais de Justice (1929-1932)

While he was known his functional architecture, he also was an innovator in decoration. As a member of the Salon d'automne, a society of artists founded in 1903 at the initiative of Frantz Jourdain, Henri Sauvage was closely connected with the leading artists of his time. He was also one of the first artists of his generation to recognize the end of the era of Art nouveau, which he abandoned in 1909. In 1913, Just before the First World War, Sauvage built a new structure for Louis Majorelle in what later became known as Art déco, making him, along with Auguste Perret, one of the pioneers in this style. It is located at 124-126 Rue de Provence, and has the simplicity and discreet decoration of the new style. Sauvage participated actively in the Exposition des arts décoratifs in Paris in 1925, which gave Art deco its name. The versatile architect designed the Pavillon Primavera (in collaboration with the architect Georges Wybo and the firm Peyret Fréres); the Tunisian bazaar, the Panorama of North Africa, the Galleria Constantine, a gallery of shops; and an electric transformer designed along with his sister-in-law, the sculptor Zette Savage.[11] For his contributions to the exhibit he was awarded the Legion of Honor in 1926.

In the 1920s, Sauvage ended his partnership with Charles Sarazin, and confirmed his status as a pioneer of the Art deco style. He designed two movie theaters in Paris; the Sèvres, at 80 rue de Sèvres in the 7th arrondissement, built in 1920 and destroyed in 1975; and the Gambetta-Palace, at 6 rue Belgrand, in the 20th arrondissement, built in 1920. The art deco interior of this theater has been remade into a cineplex, and the entrances have been modified, but the facade is in its original form. Other works in Paris included an apartment building at 137 boulevard Raspail (1922), next to one of his earlier buildings at 26 rue Vavin; Number 4 and 6, Avenue Sully-Prudhomme in the 7th arrondissement, a building crowned with sculptural decoration by François Pompon; and in 1924, the building at 14-16 boulevard Raspail, Paris in the 7th arrondissement; the building at 22-24 rue Beaujon, Paris in the 18th arrondissement; at 42 rue de la Pomp in the 16th arrondissement; and at 50 avenue Duquesne and 12 rue Éblé in the 7th arrondissement. In 1926 he built an apartment building at 19 boulevard Raspail in the 7th arrondissement, and one at 8 bis boulevard Maillot at Paris in Neuilly-sur-Seine.

In 1927, he completed the Studio-Building, a luxury apartment building of apartments in duplex, located at 65 Rue Jean-de-La-Fontaine in the 16th arrondissement, which was entirely covered by ceramic tiles by the firm of Gentil & Bourdet; multi-colored tiles facing the street, and shining white tiles facing the courtyard. The Studio-Building was his response to the 1922 real estate project of Le Corbusier for 120 villas stacked on top of each other. He took its name from the famed building of artist's studios built by Richard Morris Hunt in New York in 1857.

From 1927 to 1931, he completed two office buildings at 8 and 10 rue Saint-Marc in the 2nd arrondissement. In 1928, he also completed a building at 28 rue Scheffer in the 16th arrondissement. From 1929 to 1932, he constructed a seven-story art deco apartment building called Vert-Galant at 42 quai des Orfèvres, next to the historic Place Dauphine and Palais de Justice, provoking a strong reaction from historic preservationists.[12] In addition to his works in Paris, in 1925, Sauvage built a villa for Jean Hallade at Combs-la-Ville, and, in 1926, two villas in a rationalist style, one for himself Saint-Martin-la-Garenne in the Yvelines Department, and a residence for Julien Reinach, at 11 villa Madrid in Neuilly-sur-Seine, in the Paris suburbs.

La Samaritaine and Decré

The La Samaritaine department store, Paris (1926-1928)

The La Samaritaine department store, Paris (1926-1928) Detail of La Samaritaine (1928)

Detail of La Samaritaine (1928) La Samaritaine, building 2 (1928)

La Samaritaine, building 2 (1928) Building 3 of La Samaritaine (1930)

Building 3 of La Samaritaine (1930) The Decré department store in Nantes (1931)

The Decré department store in Nantes (1931)

In 1930, Sauvage became engaged in his final large project, the expansion of the department store La Samaritaine, a city landmark in the center of the city next to the Seine. The earlier building had been constructed between 1903 and 1910 by his long-time friend and collaborator, Frantz Jourdain. In reconstructing and expanding the store, Sauvage preserved many of the art nouveau touches and decorations of the earlier building, while making a new Paris landmark of art deco design. He worked on the building from 1925 to 1928, and in 1930 constructed a third building for the store.[13]

In 1931, also in collaboration with Jourdain, Sauvage built a second department store, called Decré, on rue Moulon in the city of Nantes. In both projects, Sauvage used his own experience and experiments with prefabricated build to build very rapidly. Once the permits were obtained and the foundations laid, the Nantes store was finished in just 97 days. It was destroyed by bombing during the war in 1943, but was rebuilt in 1949.

The facades of the new Samaritaine allowed Sauvage to practice on a monumental scale the techniques which he earlier had only been able to use on expensive smaller buildings for private clients; Vast walls of windows, filled with light, made the store a luminous landmark of the new style in the heart of historic Paris.[14][15]

From 1929 until 1931, he taught architecture at the École nationale supérieure des arts décoratifs. Many of his early works in the Art nouveau style were destroyed, and others, including the villa Marcot à Compiègne, and in poor condition. Beginning in 1975, his major works were classified as historic monuments by the Ministry of Culture. Twenty marble mosaics made from Sauvage's cartoons decorate the Art Deco lobby of Carnegie Library of Reims.[16]

See also

- Art Deco in Paris

- Concours de façades de la ville de Paris of which he was one of the winners in 1926.

Notes

- H. Guimard, Le Castel Béranger - Œuvre d’Hector Guimard (1894-1898), Paris, Librairie Rouam et Cie, 1898.

- Ph. Thiébaut (dir.), Guimard, Paris, musée d’Orsay/Réunion des musées nationaux, 1992.

- For his connection with Charpentier, see E. Héran (dir.), Alexandre Charpentier (1856-1909). Naturalisme et Art Nouveau, catalogue d’exposition, Paris, musée d’Orsay/Nicolas Chaudun, 2008.

- L.-Ch. Boileau, « Causerie - La villa Majorelle », L’Architecture, n°40, 5 octobre 1901, p. 342-348. F. Jourdain, "La villa Majorelle à Nancy", La Lorraine artiste, n°16, 15 août 1902, pp. 242-250.

- République française, ministère du Commerce, de l’Industrie, des Postes et des Télégraphes, Exposition universelle internationale de 1900 à Paris - Rapport Général administratif et technique, par M. Alfred Picard, membre de l’Institut, Président de section au Conseil d’État, Commissaire général, Paris, Imprimerie Nationale, 1902-1903, 8 vol.

- Dix ans de lutte contre le taudis. L’œuvre de la Société Anonyme des Logements Hygiéniques à Bon Marché, Paris s.d. (v. 1911). Archives Henri Sauvage, Centre d'archives d'architectes du XIX Siecle.

- Poisson 2009, p. 319.

- F. Loyer, H. Guéné, Henri Sauvage, les immeubles à gradins, Paris/Liège, IFA/Mardaga, 1987.

- H.-R. Hitchcock, Architecture : dix-neuvième et vingtième siècles, [1958], Bruxelles, Mardaga, 1981.

- J.-B. Minnaert, « Allégorie du système de construction en gradins », dans Alain Guiheux et Jean Dethier (dir.), La Ville, Art et Architecture en Europe 1870-1993, catalogue d’exposition, Paris, Centre Georges Pompidou, 1994, p. 198. J.-B. Minnaert, Henri Sauvage (1873-1932) – Projets et architectures à Paris, catalogue d’exposition aux Archives de Paris, numéro thématique de Colonnes (Institut français d’architecture), n° 6, September 1994.

- M. Chrétien-Lalanne, « Promenade d’un sceptique à travers l’Exposition des arts décoratifs et industriels modernes », L’Architecture, 25 April 1925, p. 105-114. A. Goissaud, « Exposition des arts décoratifs », La Construction moderne, 3 May 1925, p. 361-371.

- G. Morice, « Immeuble du Vert-Galant quai des Orfèvres par M. Sauvage, architecte », L’Architecture, n° 10, 15 October 1933, p. 337-344. « Chronique du vandalisme (suite). Les monuments français en péril. Sept étages pour déshonorer un site », Bulletin de l’art ancien et moderne, novembre 1932, p. 331.

- L. Escande, « Les Grands Travaux de la Samaritaine », La Technique des Travaux, December 1933.

- J. Duiker, « Henri Sauvage », De 8 en Opbouw (Pays-Bas), n° 11, 26 mai, p. 103-108.

- S. Giedion, Bauen in Frankreich Eisen Eisenbeton, Leipzig, Berlin, Klinkhardt und Biermann, 1928, trad. fra. Construire en France en fer en béton, Paris, Éditions de la Villette, 2000.

- Bibliothèque de Reims. "Plus d'informations sur la bibliothèque Carnegie et son histoire" (in French). Archived from the original on 2009-02-13. Retrieved 2010-04-03.

Bibliography

- Plum, Giles (2014). Paris architectures de la Belle Epoque. Parigramme. ISBN 978-2-84096-800-9.

- Poisson, Michel (2009). 1000 Immeubles et monuments de Paris. Parigramme. ISBN 978-2-84096-539-8.

- Texier, Simon (2012). Paris- Panorama de l'architecture. Parigramme. ISBN 978-2-84096-667-8.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Henri Sauvage. |