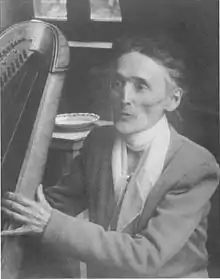

Henriette Renié

Henriette Renié (French: [ʁə.nje]; 18 September 1875 – 1 March 1956) was a French harpist and composer who is known for her many original compositions and transcriptions, as well as codifying a method for harp that is still used today. She was a musical prodigy who excelled in harp performance from a young age, advancing through her training rapidly and receiving several prestigious awards in her youth. She was an exceptional instructor and contributed to the success of many students. She gained prominence as a woman in an era where fame was socially unacceptable for women. Her devotion to her religion, her family, her students, and her music has continued to influence and inspire musicians for decades.

Henriette Renié | |

|---|---|

| |

| Background information | |

| Born | September 18, 1875 Paris, France |

| Died | March 1, 1956 (aged 80) Paris, France |

| Genres | Classical |

| Instruments | Harp |

| Years active | 1886–1955 |

Early career

Before the age of five, Henriette played piano with her grandmother. Renié was inspired to learn the harp after she heard her father perform a concert in Nice featuring Alphonse Hasselmans, a prominent harpist. She became inspired by the music and she decided that she wanted to play the harp under the instruction of Hasselmans. She began playing when she was eight, but she was still too short to reach the harp's pedals, so her father invented extended foot pedals to assist her.[1]:4

In 1885, she became a regular student at the Paris Conservatoire. At ten, she won the second prize in harp performance. The audience unanimously voted to give her first prize, but the director of the Conservatoire, Ambroise Thomas, suggested she not receive it, because that would consider her a professional and she would no longer be able to receive lessons at the Conservatoire.[1]:4 By age eleven, she won the Premier Prix.[2]:200 Her performance at the concours is largely regarded as one of the greatest performances in the history of the Conservatoire.[3]:8 At a young age, she began performing for many prominent figures such as Queen Henriette of Belgium, Princess Mathilde, and the Emperor of Brazil.[3]:9 At age twelve and following her success at the Conservatoire, students from all over Paris began seeking her out for lessons, many of them more than twice her age.[3]:10

After her graduation at thirteen, an exception was made for her to take harmony classes at the Conservatoire, which did not normally allow students under fourteen in harmony and composition. In 1891, she won the Prix de Harmonie and in 1896 she won the Prix de Contrepoint Fugue et Composition. Her professors Théodore Dubois and Jules Massenet encouraged her to compose, but she was reluctant to attract attention; she hid Andante Religioso for six weeks before she showed it to them.[3]:10 At fifteen, Renié gave her first solo recital in Paris.[4]:233

Late career

In 1901, Renié completed the Concerto in C minor that she had begun composing while at the Conservatoire. On the advice of Dubois, she showed it to Camille Chevillard, who scheduled it for several concerts. She made strides in the world of women in music during these concerts as she received the first applause directed towards a woman for both her performance and composition. These concerts established Renié, not only as a virtuoso, but as a composer, and helped establish the harp as a solo instrument, inspiring other composers such as Gabriel Pierné, Claude Debussy, and Maurice Ravel to write for harp.[3]:11

In 1903, she composed a substantial harp solo called Légende, inspired by the poem Les Elfes by Leconte de Lisle. The same year, Renié presented eleven-year-old Marcel Grandjany to the Conservatoire, but Hasselmans denied him admittance; the next year, Grandjany was accepted as a student but not allowed to compete. This was due to the growing animosity that Hasselmans had for Renié as he realized his young female student was becoming greater than himself. At age thirteen, the first time he was permitted to enter the competition, Grandjany won the Premier Prix. Following his win, he enjoyed a long and successful career as he introduced the Renié method to the United States at the Juilliard School.[5]:70–71

In 1912, Hasselmans and Renié were reconciled; he announced that he was physically unable to teach at the Conservatoire and wanted her to take his position, although no female professors were teaching advanced instrumental classes. However, the Conservatoire, as a governmental institution, required approval from the Ministry of Education for its appointments. During the French Third Republic, there was a movement to separate the church and the state and Renié vocally supported the Catholic Church. Thus, she was not hired and Marcel Tournier was given the position.[5]:78–82 Instead, she started an international competition in 1914, the "Concours Renié,".[6] This included a significant sum of money along with the prize, and had notable musicians on the jury over the years, including Ravel, Grandjany, and Pierné.[3]:15

During World War I, Renié survived by giving lessons, and gave charity concerts almost nightly, going to a fund called the "Petite Caisse des Artists" that gave immediately and anonymously to artists in need, even when a battle was being fought 90 kilometers from Paris and Big Bertha was bombarding the city.[5]:87–89 After the war, Arturo Toscanini offered Renié a contract, which she declined because her mother's health was failing.[7] In 1922, she was recommended for the Legion of Honor, but she was rejected for her religious beliefs.[7]

Renié began making recordings in 1926 for Columbia and Odéon. Her recordings sold out within three months, and Danses des Lutins won a Prix du Disque, but the recording sessions exhausted Renié, so she refused to sign any new contracts despite her success. In 1937, Renié began complaining in her diary about fatigue and overexertion; illness forced her to postpone and cancel concerts, which had become painful and draining.[5]:98–101

During World War II, Renié, at the request of her publisher Alphonse Leduc, wrote the Harp Method, which became her main focus during the war. In two volumes, it is a thorough treatment of harp technique and music. It was adopted by such important harpists as Grandjany, Mildred Dilling, and Susann McDonald. After the Armistice, students, predominantly American, flocked to Renié and spread her teaching to conservatories over the world.[4]:237

Severe sciatica and neuritis, as well as bouts of bronchitis, pneumonia, and digestive infections in winter, nearly disabled Renié, but she continued giving lessons and concerts despite the intense level of sedatives she was taking.[5]:122 When Tournier retired from the Conservatoire after 35 years, Renié was offered the job, but declined, (amusedly) saying she was four years older than Tournier.[7]:111 She was given the Legion of Honor in 1954.[8] The next year, she gave a concert, featuring Légende, saying it was the last time she would play it, and died a few months later in March, 1956 in Paris, France.[4]:229[5]:123–124

Family

Henriette's father, Jean-Émile Renié, was the son of an architect.[4]:229 He was gifted in the field but his passion was painting which he pursued after the passing of his father.[1] He studied with Théodore Rousseau, but to survive, he became an actor and a singer and then joined the Paris Opera.[1]:1 Henriette's mother, Gabrielle Mouchet was related to the well-known Parisian furniture-maker Jacob Desmalter and was a distant cousin of Jean-Émile. Her father was adamantly opposed to their marriage, but M. Mouchet eventually gave in after insisting that Jean-Émile continue to pursue his career as a painter.[1]:1The couple had four sons before Henriette was born in Paris, France.[3]:5[4]:229 The oldest three were harsh with her, but she was deeply attached to the fourth, François, and would become listless and unhappy apart from him. At one point, Henriette's nose was broken while she played with her brothers, which is why her nose is asymmetric.[5]:25 Renié kept a close relationship with her parents and was fond of her nephews and nieces, but distanced herself from them because her sisters-in-law were jealous. When Renié's father died, she lost twenty pounds in a short time and began supporting her mother financially. She also remained close to her brother François, who was isolated because of his deafness and poor vision.[5]:78

Personal life

While Henriette was in her teens, the family spent summers in Étretat, Normandy, and Henriette had a rare chance to interact with people her age. She was mutually attracted to one of her brother's friends but decided she could not sacrifice her art and career to living with him. She also rejected marrying Henri Rabaud three years later. Henriette also paid for her brothers' riding, because they were not making much money in the military.[5]:45–47

In addition to supporting her brothers as officers, she paid for a new harp for herself. Still, though she was struggling financially, she refused to take a commission on the many harps she picked for her students at Erard, and sometimes gave lessons for free.[5]:48 As a teenager, Renié worked constantly and had only one friend, Hasselmans's daughter, who was also her student.[5]:43 Later on, she became close to the Chevillards, especially his nearly blind wife, a singer and a spiritual inspiration for Renié.[5]:67

Shortly before World War I, Renié became friends with the family of one of her students, Marie-Amélie Regnier. After winning the Premier Prix and being introduced to Théodore Dubois, Marie-Amélie swore that Renié would be the godmother of her first child.[5]:84 During the war, Renié undertook the family's financial support. When the war was over, Marie-Amélie got married and presented Renié her goddaughter, and because Marie-Amélie's husband, Georges Pignal, was an engineer who was frequently absent because of contracts in Morocco, the child spent more time with her grandmother and godmother than her parents.[5]:94 In 1923, Renié helped Louise Regnier (Marie-Amélie's mother) buy a portion of a house.[5]:93 She moved in with the Regniers, along with her brother François, shortly after her mother died.[5]:93 In 1934, Louise Regnier died and left the goddaughter, Françoise, in Renié's devoted care.[5]:100 Sometimes, Renié would ride in back of Françoise's motorcycle. Despite Marie-Amélie's former gratitude and Renié's generosity to the family, the former pupil was a hostile housemate and tried to evict the Reniés, but Françoise fought her family to save Renié from financial ruin.[5]:113–114

Renié was deeply religious and when the Third Republic was trying to separate the church and state, she ostentatiously wore a gold cross to show her support.[7] Because of this, the government kept a file on her, as they did for all citizens they considered enemies of the regime.[5]:80 She was generally assertive with her beliefs; she also tore down German propaganda posters despite the fears of her friends and students.[5]:107

Legacy

Renié was critical in promoting the double-action harp of Sebastian Erard, and inspired the creation of the chromatic harp through an offhand complaint about pedals to Gustave Lyon, who worked for a manufacturer of musical instruments, including harps. Ironically, Renié demonstrated the rival Erard harp at the Brussels World's Fair, and was the major cause of its demise.[4]:233 Salvi, Erard's successor, created a "Renié" model harp, and the French Institute created a "Henriette Renié Prize for Music Composition for the Harp."[5]:106 Her Méthode complète de harpe is still widely used by aspiring harpists today.[3]:121 She published many works with major French publishers which have been mainstays of the harp repertoire for harpists of her lineage. Additional works may remain in the manuscript but have been lost.[3]:157–158 As of 2018, archives for Henriette Renié can be found at the International Harp Archives in the Special Collections of Harold B. Lee Library at Brigham Young University. These include personal letters and correspondence, concert programs, diaries, official documents, and miscellaneous personal artifacts.[9]

Works

- Andante religioso, pour harpe et violon ou violoncelle (éd. Louis Rouhier)

- Contemplation (1898, éd. H. Lemoine 1902)

- Concerto en ut pour harpe (1900 éd. Louis Rouhier : Gay & Tenton, successeurs) Dédice : « À mon cher maître Monsieur Alphonse Hasselmans, Professeur de Harpe au Conservatoire National de Musique »

- Légende after Les elfes by Leconte de Lisle (1901, éd. Louis Rouhier 1904)

- Pièce symphonique in three episodes, for harp (1907, éd. Louis Rouhier 1913)

- Ballade fantastique based on « Le cœur révélateur » by Edgar Poe, for harp solo, 1907

- Scherzo-fantaisie pour harpe (ou piano) et violon (éd. 1910)

- Six pièces pour harpe, 1910

- Danse des Lutins, for harp (1911, éd. Gay & Tenton 1912)

- 2e ballade (éd. Louis Rouhier 1912)

- Six pièces brèves, pour harpe (éd. Louis Rouhier 1919)

- Deux pièces symphoniques, pour harpe et orchestre (I. Élégie, II. Danse caprice) (éd. Louis Rouhier 1920)

- Trio pour harpe, violon et violoncelle[8]

Arrangements

- Jacques Bosh, Passacaille : sérénade pour guitare (Lemoine & Fils 1885)

- Théodore Dubois, Ronde des archers (éd. Alphonse Leduc 1890)

- Chabrier, Habanera (Enoch & Cie. 1895)

- Auguste Durand, Première valse, Op. 83 (Durand 1908)

- Bach, Dix pièces (éd. Louis Rouhier 1914)

- Bach, Dix préludes : tirés du clavecin bien tempéré (éd. Louis Rouhier 1920)

- Debussy, En bateau, extrait de la Petite suite (Durand)

- Théodore Dubois, Sorrente (Alphonse Leduc)

Incipit from Danse des Lutins

Discography

Recordings

- Henriette Renié enregistrements inédits, 1927–1955: compositions & transcriptions (1927 and 1955, Association Internationale des Harpistes)

- Henriette Renié, Danse des lutins (78rpm Columbia D 6247 matrice L 382)[10]

- Godefroy, Étude de concert (78rpm Columbia D 6247 matrice L 383)

Other records

- Trio pour harpe, violon et violoncelle – Œuvres pour harpe seule, Xavier de Maistre, harp ; Ingolf Turban, violin ; Wen-Sinn Yang, cello (1999, "Nouveaux interprètes" Harmonia Mundi HMN911692 / "Musique d'abord")

- Concertos pour harpe français – Xavier de Maistre, harp ; Staatsorchester Rheinische Philharmonie, dir. Lü Shao-Chia (2002, Claves CD 50-2206)

- Concerto en ut mineur pour harpe et orchestre – Emmanuel Ceysson, Orchestre régional Avignon Provence, dir. Samuel Jean (September 2014, Naïve)

- Henriette Renié, musique de chambre, by the Trio Nuori (2018, Ligia Digital)

Notable students

- Marcel Grandjany[2]:242

- Mildred Dilling[4]:56

- Susann McDonald[5]:110

- Odette Le Dentu[4]:237

References

- de., Montesquiou, Odette (2006). The legend of Henriette Renié = Henriette Renié et la harpe. Haefner, Jaymee, 1976–, Kilpatrick, Robert M., McDonald, Susann, 1935–. Bloomington, Ind.: AuthorHouse. ISBN 9781425954697. OCLC 126220145.

- Roslyn., Rensch (1989). Harps and harpists. London: Duckworth. p. 200. ISBN 0715622161. OCLC 18414619.

- Haefner, Jaymee (2017). One Stone to the Building: Henriette Renié's Life Through Her Works for Harp. Bloomington, IN: AuthorHouse.

- Milton), Govea, W. M. (Wenonah (1995). Nineteenth- and twentieth-century harpists : a bio-critical sourcebook. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. ISBN 0313278660. OCLC 650310430.

- des Varennes, Françoise (1990). Henriette Renié Living Harp. Bloomington: Music Works-Harp Editions.

- "Henriette Renié". www.mvdaily.com. Retrieved 2018-01-18.

- "The descriptive miniatures of Alphonse Hasselmans and Henriette Renié: An examination of the pedagogical and artistic significance of salon pieces for harp – ProQuest". ProQuest 1372275844. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Slaughter, Constance Caroline (1992), "Henriette Renié: A pioneer in the world of the harp", Rice University Missing or empty

|url=(help) - "Henriette Renié manuscripts arranged by Françoise des Varennes for her biography". findingaid.lib.byu.edu. Retrieved 2018-02-01.

- Renié, Henriette (1912). Danse des lutins : pour harpe. Harold B. Lee Library. Paris : Gay & Tenton.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Henriette Renié. |

- Harp scores by Renié on archive.org from the International Harp Archives

- Free scores by Henriette Renié at the International Music Score Library Project (IMSLP)

- Music of Henriette Renié