Henry Ossawa Tanner

Henry Ossawa Tanner (June 21, 1859 – May 25, 1937) was an American artist and the first African-American painter to gain international acclaim.[1] Tanner moved to Paris, France, in 1891 to study, and continued to live there after being accepted in French artistic circles.[2] His painting entitled Daniel in the Lions' Den was accepted into the 1896 Salon,[3] the official art exhibition of the Académie des Beaux-Arts in Paris.

Henry Ossawa Tanner | |

|---|---|

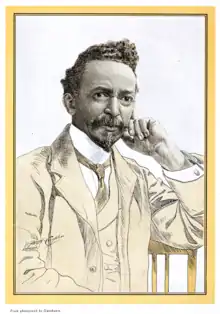

Henry Ossawa Tanner in 1907 by Frederick Gutekunst | |

| Born | Henry Ossawa Tanner June 21, 1859 |

| Died | May 25, 1937 (aged 77) |

| Nationality | American |

| Known for | Painting, drawing |

After his own self-study in art as a young man, Tanner enrolled in 1879 at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in Philadelphia. The only black student, he became a favorite of the painter Thomas Eakins, who had recently begun teaching there. Tanner made other connections among artists, including Robert Henri. In the late 1890s he was sponsored for a trip to the Mutasarrifate of Jerusalem by Rodman Wanamaker, who was impressed by his paintings of biblical themes.

Early life

Tanner was born in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, the first of nine children; two of them, Benjamin and Horace, died in infancy.[4] One of his sisters, Halle Tanner Dillon Johnson, was the first woman to be certified to practice medicine in Alabama.[5] His middle name commemorated the struggle at Osawatomie between pro- and anti-slavery partisans.[6] His father Benjamin Tucker Tanner (1835-1923) was a bishop in the African Methodist Episcopal Church, the first independent black denomination in the United States. Being educated at Avery College and Western Theological Seminary in Pittsburgh, he developed a literary career.[7] In addition, he was a political activist. His mother Sarah Tanner was born into slavery in Virginia but had escaped to the North via the Underground Railroad.

The family moved to Philadelphia when Tanner was young. There his father became a friend of Frederick Douglass, sometimes supporting him, sometimes criticizing.[8] When Tanner was about 13 years old he decided he wanted to be a painter when he saw a landscape painter working while he was walking through Fairmount Park with his father.[4]

Education

.jpg.webp)

Although many artists refused to accept an African-American apprentice, in 1879 Tanner enrolled at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in Philadelphia, becoming the only black student.[8] His decision to attend the school came at an exciting time in the history of artistic institutional training. Art academies had long relied on tired notions of study devoted almost entirely to plaster cast studies and anatomy lectures. This changed drastically with the addition of Thomas Eakins as "Professor of Drawing and Painting" to the Pennsylvania Academy. Eakins encouraged new methods, such as study from live models, direct discussion of anatomy in male and female classes, and dissections of cadavers to further familiarity and understanding of the human body. Eakins's progressive views and ability to excite and inspire his students would have a profound effect on Tanner. The young artist proved to be one of Eakins' favorite students; two decades after Tanner left the Academy, Eakins painted his portrait, making him one of a handful of students to be so honored.[9]

At the Academy Tanner befriended artists with whom he kept in contact throughout the rest of his life, most notably Robert Henri, one of the founders of the Ashcan School. During a relatively short time at the Academy, Tanner developed a thorough knowledge of anatomy and the skill to express his understanding of the weight and structure of the human figure on the canvas.[3]

Issues of racism

Although he gained confidence as an artist and began to sell his work, he had to deal with racism in Philadelphia. It had traditionally had strong ties to the South through numerous planter families and commercial ties; in addition, planters had sent their daughters to Philadelphia academies. After the Civil War, many African Americans left the rural South and settled in Northern urban centers, at times coming into conflict with the increasing population of immigrants from Ireland, southern and eastern Europe. Although painting became a therapeutic source of release for Tanner, the lack of acceptance in society was painful. In his autobiography, The Story of an Artist's Life, Tanner describes the burden of racism:

I was extremely timid and to be made to feel that I was not wanted, although in a place where I had every right to be, even months afterwards caused me sometimes weeks of pain. Every time any one of these disagreeable incidents came into my mind, my heart sank, and I was anew tortured by the thought of what I had endured, almost as much as the incident itself.[10]

Life abroad

In the hope of earning enough money to travel to Europe, Tanner operated a photography studio in Atlanta during the late 1880s. The venture was unsuccessful. During this period Tanner met Bishop Joseph Crane Hartzell, a trustee of Clark College. Hartzell and his wife befriended Tanner, became his patrons, and recommended him for a teaching job at the college.[11] Tanner taught drawing at Clark College (now Clark Atlanta University) for a short period.[12]

In 1891 he traveled to Paris, France, to study at the Académie Julian. He also joined the American Art Students Club. Paris was a welcome escape for Tanner; within French art circles the issue of race mattered little. Tanner acclimated quickly to Parisian life. Except for occasional brief returns home, he spent the rest of his life there.

In Paris, he was introduced to many new artists whose works would affect the way in which Tanner painted. At the Louvre, he encountered and studied the works of Gustave Courbet, Jean-Baptiste Chardin and Louis Le Nain.[13] These artists had painted scenes of ordinary people in their environment and the effect in Tanner's work is noticeable. The influence of Courbet's The Stone Breakers (1850; Destroyed) can be seen in the similarities painted by Tanner in his The Young Sabot Maker (1895). Both paintings explore the theme of apprenticeship and manual labor.[13]

He studied under renowned artists such as Jean Joseph Benjamin Constant and Jean-Paul Laurens.[10] With their guidance, Tanner began to establish a reputation. He settled at the Étaples art colony in Normandy. Earlier Tanner had painted marine scenes of man's struggle with the sea, but by 1895 he was creating mostly religious works. Tanner's shift to painting biblical scenes occurred as he was experiencing a spiritual struggle, evidenced by a letter he wrote to his parents on Christmas 1896 in which he stated, "I have made up my mind to serve Him [God] more faithfully."[14] A transitional work from this period is the recently rediscovered painting of a fishing boat tossed on the waves, which is held by the Smithsonian American Art Museum.[15]

This is based on the description of a miracle in the Gospel of Matthew in which "the boat was now in the middle of the sea, tossed by the waves, for the wind was contrary" (14:24). The simple resources at Étaples were well adapted to his subject matter, which in several cases featured biblical figures in dark interiors.

His painting entitled Daniel in the Lions' Den was accepted into the 1896 Salon.[3] Later that year he painted The Resurrection of Lazarus.[16] The critical praise for this piece solidified Tanner's position in the artistic elite and heralded the future direction of his paintings, which treated mostly biblical themes. Upon seeing The Resurrection of Lazarus,[17] art critic Rodman Wanamaker offered to cover an all expenses-paid trip for Tanner to the Middle East.[3] Wanamaker felt that any serious painter of biblical scenes needed to see the environment firsthand and that a painter of Tanner's caliber was well worth the investment.

Tanner quickly accepted the offer. Before the next Salon opened, Tanner set forth for the Palestine region in the Levant. Explorations of various mosques and biblical sites as well as character studies of the local population allowed Tanner to further his artistic training. His paintings developed a powerful air of mystery and spirituality. Tanner was not the first artist to study the Middle East in person. Since the 1830s, interest in Orientalism had been growing in Europe. Artists such as Eugène Delacroix, David Roberts, and, later, Henri Matisse made such tours to capitalize on this curiosity.[3]

In his adopted home of France, he was given one of its highest honors in 1923, when he was appointed Chevalier of the Legion of Honor, the highest national order of merit, and considered this "citation by the French government to be the greatest honor of his illustrious career."[18]

The Banjo Lesson

In 1893 on a short return visit to the United States, Tanner painted his most famous work, The Banjo Lesson, while in Philadelphia. The painting shows an elderly black man teaching a boy, assumed to be his grandson, how to play the banjo. This deceptively simple-looking work explores several important themes. Blacks had long been stereotyped as entertainers in American culture, and the image of a black man playing the banjo appears throughout American art of the late 19th century. Thomas Worth,[19] Willy Miller, Walter M. Dunk, Eastman Johnson, and Tanner's teacher Thomas Eakins had tackled the subject in their artwork.[13]

These images are often reduced to a minstrel-type portrayal. Tanner painted a sensitive reinterpretation. Instead of a generalization, the painting portrays a specific moment of human interaction. The two characters concentrate intently on the task before them. They seem to be oblivious to the rest of the world, which enlarges the sense of real contact and cooperation. The skillfully painted portraits of the individuals make it obvious that these are real people and not types.

In addition to being a meaningful exploration of human qualities, the piece is masterfully painted. Tanner's use of a muted palette creates a peaceful scene that emphasizes modesty and family.[20] There are two separate and varying light sources: A natural white, blue glow from outside enters from the left while the warm light from a fireplace is apparent on the right. The figures are illuminated where the two light sources meet; some have hypothesized this as a manifestation of Tanner's situation in transition between two worlds, his American past and his newfound home in France.[13]

Painting style

Tanner is often regarded as a realist painter,[21] focusing on accurate depictions of subjects.[22] While works such as The Banjo Lesson were concerned with everyday life as an African American, Tanner later painted themes based on religious subjects, for which he is now best known.[12] It is likely that Tanner's father, a minister in the African Methodist Episcopal Church, was a formative influence for him.[3]

Tanner's body of work is not limited to one specific approach to painting and drawing. His works vary from meticulous attention to detail in some paintings to loose, expressive brushstrokes in others. Often both methods are employed simultaneously. Tanner was also interested in the effects that color could have in a painting.[23] Many of his paintings accentuate a specific area of the color spectrum. Warmer compositions such as The Resurrection of Lazarus (1896) and The Annunciation (1898) express the intensity and fire of religious moments, and the elation of transcendence between the divine and humanity. Other paintings emphasize cool hues, which became dominant in his work after the mid-1890s. A palette of indigos and turquoise—referred to as the "Tanner blues"—characterizes works such as The Three Marys (1910), Gateway (1912) and The Arch (1919).[20] Works such as The Good Shepherd (1903) and Return of the Holy Women (1904) evoke a feeling of somber religiosity and introspection. Tanner often experimented with light in a composition. The source and intensity of light and shadow in his paintings create a physical, almost tangible space and atmosphere while adding emotion and mood to the environment. Tanner also used light to add symbolic meaning to his paintings. In The Annunciation (1898) the angel Gabriel is represented as a column of light that forms, together with the shelf in the upper left corner, a cross.[24] This view of the representation of Gabriel is consistent with James Romaine's comment that "Through the visual language of her pose and expression Tanner draws the viewer into Mary's inner life of virtue, trepidation, acceptance, and wonderment."[25] Mary's acceptance includes her acceptance of the cross that she will have to bear by consenting to be the Lord's handmaid (Luke 1:38).

Marriage and family

In 1899 he married Jessie Olsson, a Swedish-American opera singer.[26] A contemporary, Virginia Walker Course, described their relationship as one of equal talents, but racist attitudes insisted the relationship was unequal: "Fan, did you ever hear of a miss [sic] Olsson of Portland? She has a beautiful voice I believe and came to Paris to cultivate it and she has married a darkey artist ... He is an awefully [sic] talented man but he is black. ... She seems like a well educated girl and really very nice but it makes me sick to see a cultivated woman marry a man like that. I don't know his work but he is very talented they say."[27] Jessie Tanner died in 1925, twelve years before her husband, and he grieved her deeply through the Twenties. He sold the family home in Les Charmes where they had been so happy together. They are buried next to each other in Sceaux, Hauts-de-Seine.[28] They had a son Jesse, who survived Tanner at his death.[12]

Later years

During World War I, Tanner worked for the Red Cross Public Information Department, during which time he also painted images from the front lines of the war.[29] His works featuring African-American troops were rare during the war. In 1923 the French state made him a knight of the Legion of Honour for his work as an artist.

Tanner met with fellow African-American artist Palmer Hayden in Paris circa 1927. They discussed artistic technique and he gave Hayden advice on interacting with French society.[30]

Several of Tanner's paintings were purchased by Atlanta art collector J. J. Haverty, who founded Haverty Furniture Co. and was instrumental in establishing the High Museum of Art. Tanner's Étaples Fisher Folk is among several paintings from the Haverty collection now in the High Museum's permanent collection.[31]

Tanner died peacefully at his home in Paris, France, on May 25, 1937.[29] He is buried at Sceaux Cemetery[32] in Sceaux, Hauts-de-Seine, which is a suburb of Paris.

Legacy

Tanner's work was influential during his career; he has been called "the greatest African American painter to date."[34] The early paintings of William Edouard Scott, who studied with Tanner in France, show the influence of Tanner's technique.[13] In addition, some of Norman Rockwell's illustrations deal with the same themes and compositions that Tanner pursued. Rockwell's proposed cover of the Literary Digest in 1922, for example, shows an older black man playing the banjo for his grandson. The light sources are nearly identical to those in Tanner's Banjo Lesson. A fireplace illuminates the right side of the picture, while natural light enters from the left. Both use similar objects as well such as the clothing, chair, crumpled hat on the floor.[13] Some other major artists Tanner mentored include William A. Harper and Hale Woodruff.[4]

Tanner's Sand Dunes at Sunset, Atlantic City (c. 1885; oil on canvas) hangs in the Green Room at the White House; it is the first painting by an African-American artist to have been purchased for the permanent collection of the White House. The painting is a landscape with a "view across the cool gray of a shadowed beach to dunes made pink by the late afternoon sunlight. A low haze over the water partially hides the sun." It was bought for $100,000 by the White House Endowment Fund during the Bill Clinton administration from Dr. Rae Alexander-Minter, grandniece of the artist.[35]

Exhibitions

- 1972. The Art of Henry Ossawa Tanner. Glen Falls, New York: The Hyde Collection.

- 1972. 19th Century American Landscape. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art.

- 1976. Two Centuries of Black American Art. Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

- 1989. Black Art Ancestral Legacy: The African Impulse in African-American Art. Dallas Museum of Art.

- 1993. Revisiting the White City: American Art at the 1893 World's Fair[19]

- 2010. Henry Ossawa Tanner and his Contemporaries,[36] Des Moines Art Center (December–February 2011).

- 2012. Henry Ossawa Tanner: Modern Spirit,[37] Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Philadelphia (January–April), then to Cincinnati Art Museum[38] (May–September) and to Houston Museum of Fine Arts (October–January 2013)

Selected works

- Seascape-Jetty (c.1876–78)

- Pomp at the Zoo (1880). Private Collection

- Joachim Leaving the Temple (c. 1882-1888). Baltimore Museum of Art

- Sand Dunes at Sunset, Atlantic City (1886). Estate of Sadie T. M. Alexander (On permanent display at the White House)

- The Banjo Lesson (1893). Hampton University Museum, Virginia

- The Thankful Poor (1894). William H. and Camille O. Cosby

- The Young Sabot Maker (1895). The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, Missouri

- Daniel in the Lions' Den (1895). Los Angeles County Museum of Art

- The Resurrection of Lazarus (1896). Musée d'Orsay, Paris

- Bishop Benjamin Tucker Tanner (1897). Baltimore Museum of Art

- Lions in the Desert (c. 1897–1900). Smithsonian American Art Museum

- The Annunciation (1898). Philadelphia Museum of Art, W.P. Wilstach Collection

- Moonlight Landscape (1898-1900). Muscarelle Museum of Art, Williamsburg, VA.[39]

- Boy and Sheep Lying under a Tree (1881). Private Collection (On display at the Philadelphia Museum of Art)

- The Good Shepherd (1903). Jane Voorhees Zimmerli Art Museum, Rutgers University

Portrait of Henry Ossawa Tanner by V. Floyd Campbell

Portrait of Henry Ossawa Tanner by V. Floyd Campbell - Return of the Holy Women (1904). Cedar Rapids Art Gallery, Iowa

- Two Disciples at the Tomb (1905–06). Art Institute of Chicago

- The Holy Family (1909–10). Muskegon Museum of Art, Michigan, Hackley Picture Fund

- Moroccan Scene (about 1912). Birmingham Museum of Art, Alabama

- Palace of Justice, Tangier (1912–13). Smithsonian American Art Museum[40]

- Scene in Cairo. Mabee-Gerrer Museum of Art, Shawnee, Oklahoma

Other works

Abraham's Oak, 1905

Abraham's Oak, 1905 A View of Fez, c. 1912

A View of Fez, c. 1912.jpg.webp) View of the Seine, looking toward Notre Dame, 1896

View of the Seine, looking toward Notre Dame, 1896 Coastal Landscape, France, 1919

Coastal Landscape, France, 1919 Fishermen at Sea, c. 1913

Fishermen at Sea, c. 1913 The Young Sabot Maker, 1895

The Young Sabot Maker, 1895 Mary, 1914

Mary, 1914 The Disciples See Christ Walking on the Water, c. 1907

The Disciples See Christ Walking on the Water, c. 1907 Angels Appearing before the Shepherds, c. 1910

Angels Appearing before the Shepherds, c. 1910 Jesus and Nicodemus, 1899

Jesus and Nicodemus, 1899 Daniel in the Lions' Den, 1907–1918

Daniel in the Lions' Den, 1907–1918 The Annunciation to the Shepherds, c. 1895

The Annunciation to the Shepherds, c. 1895

Sand Dunes at Sunset, Atlantic City, c. 1885, the White House.

Sand Dunes at Sunset, Atlantic City, c. 1885, the White House. Destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah, 1929–30, High Museum of Art

Destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah, 1929–30, High Museum of Art

Notes

- "Henry Ossawa Tanner". Archived from the original on May 27, 2011. Retrieved August 5, 2006.

- Marcia M. Mathews (1995). Henry Ossawa Tanner: American Artist. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-51006-9.

- Matthews, Marcia. Henry Ossawa Tanner: American Artist. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1969.

- Woods, Naurice Frank (2018). Henry Ossawa Tanner Art, Faith, Race, and Legacy. New York, NY: Taylor and Francis. ISBN 9781138241947.

- Wright, A. J. (May 18, 2017). "Halle Tanner Dillon". Encyclopedia of Alabama. Retrieved November 8, 2020.

- Kelly Jeanette Baker. "Race, Religion, and Visual Mysticism". Florida State University. Missing or empty

|url=(help) - The Civil War in America: Benjamin Tucker Tanner, Library of Congress Exhibitions

- Finkelman, Paul, ed. (2006). Encyclopedia of African American History 1619-1895. 3. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 224.

- Parry, Ellwood C. III. Three Nineteenth Century Afro-American Artists. Cedar Rapids, IA: Cedar Rapids Art Center, 1980.

- Bruce, Marcus C. Henry Ossawa Tanner. New York: The Crossroad Publishing Company, 2002.

- Matthews, Marcia (1994). Henry Ossawa Tanner: American Artist. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. p. 36. ISBN 0226510069.

- "Henry Ossawa Tanner". Springfield Museum of Art. Archived from the original on January 10, 2006. Retrieved August 5, 2006.

- Shaw, Thomas M. What Manner of Men? A Reconsideration across the Synapses of Art History of Three Paintings and their Images of Men of African Descent. Lanham, MD: University Press of America, 1997.

- Woods, Naurice Frank. “Embarking on a New Covenant: Henry Ossawa Tanner’s Spiritual Crisis of 1896.” American Art, vol. 27, no. 1, 2013, pp. 94–103. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/10.1086/670686.

- Details on the museum site

- "Negro Artist site". Negroartist.com. Retrieved December 14, 2013.

- "Negro Artist site". Negroartist.com. Retrieved December 14, 2013.

- Mosby, Dewey F.; Sewell, Darrell; Alexander-Minter, Rae (1991). Henry Ossawa Tanner: catalogue. Philadelphia, PA: Philadelphia Museum of Art. p. 32. ISBN 0-87633-086-3.

- Woods, Naurice Frank, Jr., Ph.D. Insuperable Obstacles: The Impact of the Creative and Personal Development of Four Nineteenth Century African American Artists. The Union Institute, 1993.

- Farrington, Lisa (2017). African-American Art A visual and Cultural History. 198 Madison Avenue, New York, New York 10016: Oxford University Press. pp. 97–98. ISBN 978-0-19-999539-4.CS1 maint: location (link)

- "Henry Ossawa Tanner Online". Retrieved August 5, 2006.

- "Realism - Realism Art". Archived from the original on October 7, 2009. Retrieved August 5, 2006.

- Kettlewell, James K. The Art of Henry Ossawa Tanner. Glen Falls, NY: The Hyde Collection, 1975.

- "Teacher Resources: The Annunciation" (PDF). The Annunciation, Henry Ossawa Tanner. Philadelphia Museum of Art. Retrieved June 6, 2016.

- Romaine, James (Summer 2012). "Henry Ossawa Tanner: Painting Belief". Art & Christianity.

- Marley, Anna O. "Introduction" in Modern Spirit Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. Philadelphia. 2012.

- Course, Virginia Walker qtd. by Jean-Claude Lesage in "Tanner, The Pillar of Trepied."Modern Spirit Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. Philadelphia. 2012, p. 88.

- Marley (2012), p. 41.

- "Henry Ossawa Tanner". Archived from the original on August 29, 2006. Retrieved August 9, 2006.

- Finkelman, Paul, ed. (2009). Encyclopedia of African American History (1896 to the present). 2. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 393.

- "Page Not Found". Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved April 1, 2015. Cite uses generic title (help)

- "Henry Ossawa Tanner". Find a Grave. Archived from the original on March 15, 2020.

- "A modest improvement at the National Gallery | Tyler Green: Modern Art Notes | ARTINFO.com". Blogs.artinfo.com. February 3, 2012. Retrieved December 14, 2013.

- Finkelman, Paul, ed. (2006). Encyclopedia of African American History 1619-1895. 1. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 101.

- "White House Announces Acquisition of Henry Ossawa Tanner Painting for Permanent White House Collection". Life in the White House.

- "Henry Ossawa Tanner and his Contemporaries", Des Moines Art Center.

- "Henry Ossawa Tanner: Modern Spirit", PAFA.

- "Upcoming Exhibitions". Archived from the original on July 3, 2014. Retrieved April 1, 2015.

- "Moonlight Landscape, (oil on canvas)". Art in Bloom. Muscarelle Museum of Art. 2016. Retrieved June 20, 2018.

- "Palace of Justice, Tangier, Morocco". World Digital Library. 1890–1900. Retrieved June 27, 2013.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Henry Ossawa Tanner. |

- White House Biography

- Springfield Museum of Art Biography

- Ebony Society of Philatelic Events and Reflections Biography

- Muskegon Museum of Art

- Profile at PBS.org

- Moroccan Scene at the Birmingham Museum of Art

- University of California Press Henry Ossawa Tanner: Modern Spirit (2012) the most complete scholarly publication to date produced in conjunction with PAFA, Tanner's Alma Mater, the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts

- Joachim Leaving the Temple (c. 1882-1888) Baltimore Museum of Art E-Museum

- Bishop Benjamin Tucker Tanner (1897) Baltimore Museum of Art E-Museum

- Smithsonian American Art Museum