Herculaneum loaf

Herculaneum loaf is a stamped sourdough loaf of bread that has been partially preserved due to being carbonised. It was baked on 24 August 79 AD at Herculaneum, and later rediscovered from the archaeological site in 1930.

The loaf was discovered from a villa owned by Quintus Granius Verus, and it also proved the ownership of the villa due to being stamped.

The loaf currently belongs into collections of the National Archaeological Museum, Naples.[1]

Preservation and discovery

The Herculaneum loaf was baked on 24 August 79 AD. The brick oven where it was placed in partially protected the loaf from being destroyed in the pyroclastic flow which followed the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 AD.[2]

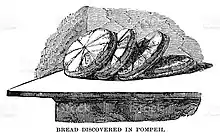

Other similar loaves of bread have been also recovered from the archaeological sites at Pompeii and Herculaneum.[3][1] One such discovery included 81 loaves of bread from a single oven.[4] However, foodstuff which has survived in Pompeii and Herculaneum, has been known to be noticeably smaller than expected. This shrinking has been caused by loss of liquid. Presumably, the surviving breads have also shrunk in size, as they were subjected to temperatures of at least 400°C. Scoring and stamping on the Herculaneum loaf seems implausibly clear due to this process of carbonisation by the pyroclastic flow.[5]

In 1930 the loaf was rediscovered.[5] The villa known as the House of the Stags was excavated between 1929–1932, and it was the location where the loaf of bread was found.[6]

The loaf is currently held at the National Archaeological Museum, Naples.[1]

Features of the bread

.jpg.webp)

Dough of the bread has been analysed and it is known to be a sourdough bread. It has been possible to recreate a recipe by analysing the bread.[2][5]

The loaf has been incised before being baked. The cuts divided the bread into wedges and made the bread easier to share. Similar loaves appear in the Roman art.[7]

The bread had been tied with a string to make it easier to carry, and to make each bread of same size. The location where the string was can be clearly seen from a line going around the side of the bread.[5]

The loaf is stamped with a text "Of Celer, slave of [Quintus] Granius Verus".[3][1] Loaves of bread were marked in this manner before being, for instance, taken into a communal bakery. The bread's original owner, Celer is known to have survived the eruption of Vesuvius, and the subsequent pyroclastic flow. His name appears in a later list of freed slaves.[3] Celer's master Quintus Granius Verus was one of the city elders, and the loaf itself is important as it proves that he owned the villa, known as the House of the Stags, where the loaf was discovered.[8] Quintus Granius Verus was also a member of a successful merchant family.[6]

References

- Eleanor Dickey (31 August 2017). Stories of Daily Life from the Roman World: Extracts from the Ancient Colloquia. Cambridge University Press. p. 105. ISBN 978-1-107-17680-5.

- Philip Matyszak (5 October 2017). 24 Hours in Ancient Rome: A Day in the Life of the People Who Lived There. Michael O'Mara. pp. 33–34. ISBN 978-1-78243-857-1.

- Nicholas P. (Professor of Botany and Western Program Director at Miami University in Oxford Money, Ohio); Nicholas P. Money (22 February 2018). The Rise of Yeast: How the Sugar Fungus Shaped Civilisation. Oxford University Press. p. 46. ISBN 978-0-19-874970-7.

- Claire Holleran (26 April 2012). Shopping in Ancient Rome: The Retail Trade in the Late Republic and the Principate. OUP Oxford. p. 131. ISBN 978-0-19-969821-9.

- The British Museum (14 June 2013). How to make 2,000-year-old-bread (Video). YouTube. Retrieved 22 July 2020.

- Sheldon, Natasha. "The House of the Stags". Ancient History and Archaeology.com. Retrieved 22 July 2020.

- Paul Erdkamp; Claire Holleran (26 October 2018). The Routledge Handbook of Diet and Nutrition in the Roman World. Taylor & Francis. p. 66. ISBN 978-1-351-10731-0.

- Mario Pagano (2000). Herculaneum: A Reasoned Archaeological Itinerary. T&M. p. 85. ISBN 978-88-87150-04-9.