History of Shreveport, Louisiana

Shreveport, Louisiana, was founded in 1836 by the Shreve Town Company, a development corporation established to start a town at the meeting point of the Red River and the Texas Trail. In this period, a 180-mile (289 km) long natural logjam, the Great Raft, had obstructed passage to shipping. The Red River was cleared and made newly navigable by Captain Henry Miller Shreve of the United States Army Corps of Engineers. Shreve used a specially modified riverboat, the Heliopolis, to remove the logjam. The company and the village of Shreve Town were named in Shreve's honor.

| History of Louisiana |

|---|

|

|

|

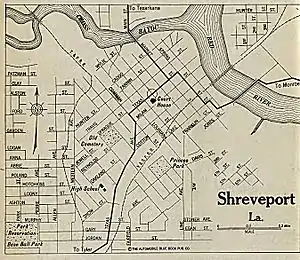

Shreve Town was originally contained within the boundaries of a section of land sold to the company by the indigenous Caddo Indians in the year of 1835, during the period of Indian Removal.[1] In 1838, Caddo Parish was created from the large Natchitoches Parish (pronounced "NACK-a-dish") and Shreve Town was designated as the parish seat. Shreveport remains the parish seat of Caddo Parish today. On March 20, 1839, the town was incorporated as "Shreveport".[1] Originally, the town consisted of 64 city blocks, created by eight streets running west from the Red River and eight streets running south from Cross Bayou, one of its tributaries.

Shreveport soon became a center of steamboat commerce, which carried mostly cotton and agricultural crops to downriver markets and goods to this trading center. Some of the cotton was shipped overland from Texas to Shreveport. The city also had a slave market in the antebellum years, although slave trading was not as important here as in New Orleans and Baton Rouge. Both slaves and free blacks worked on the river steamboats which plied the Red River, and as stevedores loading and unloading cargo. By 1860, Shreveport had a free population of 2,200 and 1,300 slaves within the city limits.

During the American Civil War, Shreveport was a Confederate stronghold and the headquarters of the Trans-Mississippi Department of the Confederate States Army. Isolated from events in the east, the civil war continued in the Trans-Mississippi theater for several months after Robert E. Lee's surrender in April 1865, and Shreveport briefly became the Confederate capital. Confederate President Jefferson Davis attempted to flee to Shreveport when he left Richmond.

1900 to present

The Red River remained navigable until 1914. By that time disuse had resulted in silt deposits, as railroad had become the preferred means of transporting goods and people. Railroads and highways became the preferred means of moving people and freight.

Shreveport's most famous musician, blues guitarist and singer Huddie William Leadbetter, a.k.a. 'Lead Belly', was born January 15, 1888, on the Jeter Plantation near Shreveport. Leadbelly frequently performed in Shreveport's red light district, St. Paul's Bottoms. After his death in 1949 while on tour in Europe, he was buried in the community of Mooringsport, just north of Shreveport. In the 1950s and 60s, he was rediscovered by younger musicians, who recognized his contributions as they explored folk and blues revivals.

Missouri-born banker Peter Youree (1843–1914), became one of the city's most prominent businessmen. He financed the ten-story Commercial National Bank Building (1910) and the Washington Youree Hotel. Youree's bank building was the city's first skyscraper. Youree Drive in Shreveport was named for him.

Barksdale Air Force Base, which opened in 1933 as Barksdale Army Air Field, is in Bossier City. It has supported US military efforts. It was part of the defense investment in this area, which accelerated during World War II.

Shreveport was home to the Louisiana Hayride, a radio broadcast from the city's Municipal Auditorium. During its heyday from 1948 to 1960, it featured musicians who became noted nationally, such as Hank Williams, Sr., and Elvis Presley (who got his start at this venue).[2]

Musician Sam Cooke was turned away from a whites-only Shreveport hotel in 1962, inspiring the song "A Change Is Gonna Come." In 2019, then-Shreveport mayor Adrian Perkins apologized to Cooke's family for the event, and posthumously awarded Cooke the key to the city.

During the late 20th century, Shreveport and Bossier City conducted surveys of historic assets and nominated significant ones for recognition. Together they now have six historic districts and numerous sites listed on the National Register of Historic Places. The original 64-block town is today the city's central business district and is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. Shreveport is second only to New Orleans among Louisiana cities in the number of historic landmarks. The historic McNeill Street Pumping Station is an 1887 waterworks that is still in use.

The city and region suffered during and after the decline of the oil business. Both blacks and whites lost good-paying work, and many people left. After the third black man had been fatally shot by whites within a few months, on September 23–24, 1988, there was rioting in black neighborhoods after charges were reduced for a defendant in a case of a young white woman fatally shooting a David McKinney, a black man who appeared to be an innocent bystander. [3]

The federal government authorized and funded a major project in the late 20th century to improve navigation on the Red River. This included construction of locks and dams, completed in the 1990s, making navigation of the river once again possible to Shreveport. Today the port of Shreveport-Bossier City is being redeveloped as a shipping center.

In the mid-1990s, in an effort to generate tourism revenues, the state authorized riverboat gambling. Development of several riverboat casinos on the Red River in Shreveport stimulated revitalization of the downtown and riverfront areas. In addition, the city conducted the "Streetscape" project, to give downtown streets a facelift through the installation of traditional brick sidewalks and crosswalks, as well as adding public art such as statues and mosaics. The Texas Street Bridge received a new lighting schemed designed in neon, which provoked a variety of opinions. This was originally accompanied by a green laser beam, which the city eventually abandoned.

President George W. Bush was taken to Barksdale AFB for safety after the first of the September 11, 2001 attacks. Later B-52 bombers based there participated in Operation Enduring Freedom in Afghanistan and Operation Iraqi Freedom in 2003. Their attacks on fixed hard targets marked a new era in U.S. air power where precision-guided munitions were used more than "dumb" bombs, with devastating effect (see Shock and Awe).

Since the downturn in the oil industry and other economic problems, the city has struggled with a declining population, unemployment, poverty, drugs and violent crime.[4] City data from 2017 showed a dramatic increase in certain violent crimes from the previous year, including a 138 percent increase in homicides, a 21 percent increase in forcible rapes and more than 130 percent increases in both business armed robberies and business burglaries.[4] In 2018 the local government and police authorities reported a crime drop in most categories; it was part of an overall reduction in crime since the late 20th century.[5] In late 2018, Shreveport was named the "worst place to live in Louisiana" and in 2019, the worst place to start a career.[6][7]

On January 16, 2020, Advanced Aero Services planned to open a facility at Shreveport Regional Airport, with an estimated 1,000 jobs by the end of the decade.[8][9]

In March 2020, Shreveport was named the fourth-fastest shrinking city by the 24/7 Wall St. online magazine.[10]

On June 19, 2020 rapper Hurricane Chris was arrested in Shreveport for second degree murder.[11][12] In July 2020, information alleging corruption in the Mayor Adrian Perkins administration was leaked.[13][14][15] A Shreveport Police officer was also placed on leave regarding comments of the George Floyd killing in Minnesota.[16][17]

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to History of Shreveport, Louisiana. |

References

- Plummer, Marguerite R. & Joiner, Gary D. (2000). Historic Shreveport-Bossier: An Illustrated History of Shreveport and Bossier City, pp. 11–12. Historical Publishing Network.

- Aswell, Tom (2010). Louisiana Rocks!: The True Genesis of Rock & Roll, p. 261. Pelican Publishing Company, Inc.

- Kevin McGill (AP), "Shreveport Blacks Angered Over Three Recent Deaths", Shreveport Times, 24 September 1988; accessed 5 May 2018

- The Shreveport Times, Police Chief Addresses Shreveport's Rising Violent Crime Archived April 10, 2019, at the Wayback Machine, 26 June 2017, retrieved 16 Dec 2017

- "Shreveport crime drops in most categories, police say". shreveporttimes.com. Archived from the original on June 13, 2018. Retrieved 2018-04-21.

- Wright, Robert J. "New Study Says Shreveport 'Worst Place To Live' In Louisiana". News Radio 710 KEEL. Archived from the original on June 1, 2019. Retrieved 2019-06-01.

- Frederick, Lauren. "New study reveals Shreveport as the worst city to start a career". Ksla.com. Archived from the original on June 1, 2019. Retrieved 2019-06-01.

- Bayliss, Deborah. "New aviation facility in Shreveport will create more than 130 new jobs". shreveporttimes.com. Retrieved 2020-01-27.

- "Forecast for economic growth in Shreveport is bright". www.ksla.com. Retrieved 2020-01-27.

- "America's 10 Fastest Shrinking Cities – 24/7 Wall St". Retrieved 2020-06-18.

- AP (2020-06-19). "Rapper Hurricane Chris arrested for murder in Louisiana". ABC13 Houston. Retrieved 2020-06-20.

- Blackmon, Danielle Scruggs, Charitee. "La. rapper Hurricane Chris arrested after deadly shooting near convenience store". www.ksla.com. Retrieved 2020-06-20.

- "(PT. 4) S.P.D. "STOPS" PERKINS FOR FOUR (4) D.U.I.'s IN 3 MONTHS". Real Shreveport. Retrieved 2020-07-22.

- "SADOW: Adrian Perkins' Senate Run Could Backfire, You Know". The Hayride. 2020-07-24. Retrieved 2020-07-25.

- Team, 3-Investigates. "Internal auditor seeks information on Mayor Perkins' alleged traffic stops". KTBS. Retrieved 2020-08-14.

- Enfinger, Emily. "SPD officer placed on leave, under administrative investigation after social media post". The Times. Retrieved 2020-07-22.

- May, Gerry. "Shreveport officer who made controversial Facebook post gets suspended". KTBS. Retrieved 2020-07-22.