History of a Voyage to the Land of Brazil

History of a Voyage to the Land of Brazil, Also Called America, (French: Histoire d'un voyage fait en la terre de Brésil; Latin: Historia Navigationis in Brasiliam, quae et America Dicitur) is an account published by the French Huguenot Jean de Léry in 1578 about his experiences living in a Calvinist colony in the Guanabara Bay in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.[1] After the colony dissolved, De Léry spent two months living with the Tupinambá Indians.

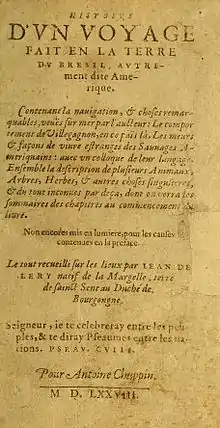

Cover of the 1578 French Edition | |

| Author | Jean de Léry |

|---|---|

| Original title | Histoire d'un voyage fait en la terre de Brésil |

| Country | France |

| Language | French |

| Publisher | pour Antoine Chuppin |

Publication date | 1578 |

Historical context

Brazil was the first area of the Americas explored by the French.[2] At the time of Jean de Léry's History of a Voyage to the Land of Brazil, Also Called America, the French and the Portuguese were in competition for control of the resources of Brazil.[2] While reports of cannibalism among the indigenous people were widespread, interactions with the natives showed that they were friendly.[3] At the time, it was common practice to use Europeans who had spent time with the indigenous peoples as interpreters to help the Europeans communicate with the natives.[2] In the years preceding de Léry's writing of History of a Voyage to the Land of Brazil, Also Called America, the Portuguese had begun their effort to completely colonize Brazil, so the influence of the French was fading, though pockets of French control and influence still existed in Brazil.[2] This fading influence coincided with the Portuguese's exploration of the Amazon river delta, though trade between the people of Brazil and the English and the Dutch was also increasing.[3] A product of the competition for control of the lands of Brazil between the French and the Portuguese in Brazil was the creation of tribal alliances, with the Tupinamba, the group referred to in History of a Voyage to the Land of Brazil, Also Called America, siding with the French against the Tupiniquim, who allied themselves with the Portuguese.[4] In this era of first contacts, the understanding of the indigenous peoples were being informed by the accounts of early explorers like de Léry and the Portuguese explorers, so much of what was known to new arrivals about the indigenous peoples game from reports like de Léry's.[3] These other accounts had some thematic similarities to de Léry's, such as the usage of tribe names to describe the people specifically, or the frequent use of gender-indicating nouns like “man” or “woman”.[4] Thus, de Léry was writing in a different historical context from those accounts emerging from Africa, which emphasized racial elements more than they emphasized gender or non-racial elements.[4]

About Léry

Jean de Léry was born to an upper-class family in 1534 in Margelle (Bourgogne), France.[5] He was well-educated; he studied theology in Geneva whilst working as a shoe-maker. Léry was alive during the Wars of Religion time-period in France between the Protestants and the Catholics.[6] It was during this time that the Genevan church was recruiting Frenchmen to be trained as missionaries of the Reformed Gospel. Léry joined this group but instead of returning to France, in November 1556, he and a group of thirteen Calvinist ministers were sent to Brazil.[7] They were to create the first Protestant mission in the New World. Upon his return to France in 1558, he got married but it is unknown whether or not he had children. He returned to Geneva to further his ministerial studies and became a Protestant minister near Lyon. He also joined Protestant troops in the French religious wars where he used knowledge he gained from his expeditions in Brazil to help him and other soldiers to survive. In 1613, he died of the plague at the age of 79.[7]

Synopsis

The book has 22 chapters, with Chapter 1 discussing the motive behind the voyage to Brazil and Chapters 2-5 describing the sights and events that occurred during the voyage to Brazil. Chapters 6-20 consist of Léry describing the land of Brazil, the physical description of the indigenous people, and the behaviors and customs of the indigenous people. Lastly, Chapters 21 and 22 recount the departure from Brazil and the trip back to France. The book contains detailed descriptions of the plants, animals, and indigenous people in the new world for the French.[8]

Themes

The Tupinamba physical constitution

Léry describes the physical characteristics of the Tupinamba people and details the modifications they make to their bodies, as well as their comfortability with being completely nude. Lery describes the constitution of the average Tupinamba person:

Not taller, fatter, or smaller in stature than we Europeans are; their bodies are neither monstrous, nor prodigious with respect to ours. In fact, they are stronger, more robust and well filled-out, more nimble, less subjected to disease; there are almost none among them who are lame; one eyed or disfigured[9]

Léry goes on to describe that some individuals that he encountered lived well beyond one hundred years old (with respect that the Tupinamba people had a different Calendar than the Gregorian Calendar), and their elders are slow to develop grey or white hair. When describing the skin tone of the average Tupinamba person Lery states

They are not particularly dark, but merely of tawny shade, like the Spanish or provencals[10]

Léry then discusses how the Tupinamba people are completely comfortable with being naked, especially the women.

We tried several times to give them dresses and shifts (as I have said we did for the men, who sometimes put them on) it has never been our power to make them wear clothes: to such a point were they resolved (and I think they have not changed their minds) not to allow anything at all on their bodies[11]

Bodily modifications

Much of the chapter is dedicated to describing various body modifications Lery witnessed among men and women of the Tupinamba nation including, but not limited to, tattoos and piercings. Lery states that men more often modify their bodies than women do. Lery describes a tradition of piercing the lower lip in young boys and inserting a bone an inch wide and that can be removed at any time. On this page he also describes how after birth, babies often have their noses pushed in to make their noses seem more attractive.

However, our Americans, for whom the beauty of their children lies in being pug-nosed, have the noses of their children pushed in and crushed with the thumb as soon as they come out of their mother’s wombs.[12]

Tattoos

Tattoos are described as being made with the dye of the genipap fruit. Lery states that often people would blacken their legs and that the dye is to a degree waterproof and can take up to twelve days to wash off. Some of these painting are put over incisions they make on their skin that show how many people they have killed.[13]

Léry also describes facial paintings. This process is noted to have involved feathers from hens, red dye from Brazilwood (he described how other tribes used other colored dyes from different objects), and boiling the feathers.[14] A gum was used as an adhesive and the feathers were chopped up with iron tools they procured from the colonists. Once this process was complete these feathers were put all over the body. Lery described how in some accounts these feathers have led to a misconception in Europe that the Tupinamba were covered in hair, and he stated this is not the case and that naturally the Tupinamba did not have a lot of hair on their bodies. It is also mentioned that feathers from a Toucan were often placed in the front of the ear and attached with an adhesive gum by many women. Ostrich feathers are also said to have been attached along a cotton thread to make a decorative hip belt.[14]

Léry states that Tupinamba people would regularly strip their bodies of hair which included eyebrows and eyelashes. Women would have their hair long, while men would typically shave their heads.[15]

Jewelry and necklaces

According to Léry, the Tupinamba people had different types of necklaces. He wrote about what the natives called a boure which was made with pieces of seashells that were polished on a sandstone which then were pierced and lined along a cotton string. Lery also notes that boure can be made with a type of 'black wood' that has a similar appearance to seashell boure. Women also made bracelets around their arms that were made of bones joined together with a gum.[16]

Civil order and everyday life

Léry describes the customs of the Tupinambá people, how the Tupinambá people live, and how they treat their guests. For the most part, Jean de Léry indicates that the Tupinambá people are peaceful, but rarely a fight breaks out between them that may end in a death.[17] The family of the deceased then has the right to kill the murderer as the Tupinambá people believe in revenge, such as a life for a life.

Léry also recounts the living setup of the Tupinambá people.[18] The houses are big and are made out of wood and pindo plants. Although families live in the same house, they are separated and have their own space, including land to plant crops. From time to time, the Tupinambá people would move their houses to a different location and when Jean de Léry asked for the reason why he was told that,

“The change of air keeps them healthier, and that if they did other than what their grandfathers did, they would die immediately” [18]

Jean de Léry then goes in depth on how women spin cotton in order to make the beds that the Tupinambá people sleep on.[19] Based on the description Jean de Léry gives, the beds are hammocks that are set up outside the houses. In addition to spinning cotton, women also do the majority of the housework and make pottery.

Cannibalism

Léry also describes an event that occurred to him regarding cannibalism.[20] When he and his interpreter made a stop at one of the villages, he was greeted accordingly and realized that the Tupinamba people were in the midst of a celebration. This celebration consisted of dancing, cooking, and eating a prisoner they had killed earlier. Jean de Léry did not want to participate in the celebration and stayed at his bed alone. However, one of the Tupinamba people came and offered him the prisoner's foot, but since Jean de Léry's interpreter was not present, he thought they were threatening to eat him. By morning, Jean de Léry realized his error and was afraid for nothing.

Treatment of guests

The customs of the Tupinambá people regarding how they treat guests consisted of seating their guests on a bed while the women wept in gratitude for their visit.[21] During this, the head of the household makes an arrow and when he is done, he greets the guest and offers them food. The guests must eat on the ground since there are no tables. After the women are done weeping, they serve the guest fruit or other small gifts. If the guest desires to sleep there, their bed is hung among several fires to keep them warm. At the end of the visit, gifts are exchanged, which are usually small since the Tupinambá people travel by walking and do not have animals to carry cargo for them. Jean de Léry praises the treatment he has received from the Tupinambá people and even compares it to the French, as he states,

“...I can’t help saying that the hypocritical welcomes of those over here who sue slippery speech for consolidation of the afflicted is a far cry from the humanity of these people, whom nonetheless we call “‘barbarians’”[22]

Lastly, Jean de Léry describes how the Tupinambá people make fires through the use of sticks only.[23] He describes their method and how they deem it necessary to have fire with them at all times due to their fear of an evil spirit called Aygnan. He ends the chapter explaining that the Tupinambá people and the French get along well because they have a common enemy: the Portuguese.

Illnesses and death

Jean de Léry describes how the Tupinambá people treat illnesses and how they handle deaths. If someone has a wound and bedridden, they are treated through suction and are not fed unless they explicitly ask for food. However, celebrations still continue as normal. The most dangerous disease that the Tupinambá people cannot treat is called pians and occurs through lechery.[24] Jean de Léry compares it to smallpox and states that it affects the entire body and lasts for a lifetime.

If someone dies, there is great mourning as Jean de Léry compares the cries of women to, “the howling of dogs and wolves.[24] The Tupinambá people comfort each other, remember the good deeds the deceased person had done, and sing in their memory. Mourning lasts half a day, until the Tupinambá proceed with burying the body in the ground with jewelry the person used to wear. Jean de Léry mentions how the Tupinambá people do not bury any valuable jewelry with dead bodies anymore since the French have arrived, perhaps due to past experiences with Europeans digging up graves for jewelry.[25] On the first night the body is buried, the Tupinambá people have a feast on the grace of the deceased person and do this until they believe the body has fully decayed.[25] The rationale behind this custom is that the Tupinambá people believe that Aygnan, the evil spirit mentioned before, is hungry and finds no other meat around, he will dig up the dead body and eat it. Thus, the celebration occurs for protection. Still, Jean de Léry finds this custom disrespectful and tried to convince the Tupinambá people not to do it through interpreters with little success. Lastly, the Tupinambá people place the plant called pindo used to build houses on graves as well so that they can recognize where their loved one was buried.

Reception

History of a Voyage to the Land of Brazil is regarded as a significant work in many fields. Reviewers of the text note the breadth of its scope and the varying opportunities for its use.[26] It is fundamental in ethnographic studies and South American ecology.[27][28] It also provides insight to history, colonizer and native languages, religion, and political theory.[26] Because of its wide disciplinary coverage, it is a valuable source for historians and colonial scholars[29] as well as geologists and biologists.[27] For colonial historians, it contributes to a greater understanding of “the meaning and significance of the European conquest of the Americas”[26] and helps to describe native people, their relationship with the Europeans, and the cognitive justifications of European domination.[26] It also details “how Brazil was created out of a fusion of Indian, European (and later African) elements”[26] and highlights larger historical themes.[26]

Reviews of Janet Whatley's 1990 English translation of History of a Voyage to the Land of Brazil are overwhelmingly favorable. There are two main components to most reviews beyond the text's significance: praise for the detail provided by de Léry and praise for Whatley's translation. De Léry describes the lives, culture, and rituals of the Tupinambá with “detailed thoroughness”[30] and is seen as exceptional in “his surprising openness to an alien culture.”[30] The great detail of de Léry's work and his willingness to intimately engage with the Tupinambá[27] is only critiqued by his “naive comparisons between the savagery of the Indians and the savagery of the Europeans.”[27] Whatley is noted as a “graceful”[30] translator and “a stylistic marvel.”[29] It is generally agreed that she was able to stay true to the charm of de Léry's prose and maintain the stylistic integrity of sixteenth-century French writing.[28] Additions made by Whatley were also received well, as the inclusion of notes on references made by de Léry were helpful reading guides and aided in the placement of de Léry's writing in historical context.[28]

External links

References

- "Rare Materials Digital Services at the University of Virginia Library". www.lib.virginia.edu. Retrieved 2018-01-03.

- Encyclopedia of Latin American history and culture. Kinsbruner, Jay,, Langer, Erick Detlef (Second ed.). Detroit: Charles Scribner's Sons. 2008. ISBN 9780684315904. OCLC 232116446.CS1 maint: others (link)

- Native Brazil : beyond the convert and the cannibal, 1500-1900. Langfur, Hal. Albuquerque. ISBN 9780826338419. OCLC 869521852.CS1 maint: others (link)

- Sadlier, D. J. (2008). Brazil Imagined: 1500 to the Present. Austin: University of Texas Press.

- "Rare Materials Digital Services at the University of Virginia Library". www.lib.virginia.edu. Retrieved 2018-02-02.

- "Millennium Web Catalog". doi:10.1093/acref/9780195149227.001.0001/acref-9780195149227-e-0801. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "Millennium Web Catalog". 0-quod-lib-umich-edu.dewey2.library.denison.edu. Retrieved 2018-02-02.

- Conrad, Elsa. "Jean de Léry (1534-1613?)". University of Virginia Library. Retrieved 2018-02-01.

- Léry, Jean de (1993). History of a Voyage to the Land of Brazil. University of California Press. p. 56. ISBN 9780520913806.

- Léry, Jean de (1993). History of a Voyage to the Land of Brazil. University of California Press. p. 57. ISBN 9780520913806.

- Léry, Jean de (1993). History of a Voyage to the Land of Brazil. University of California Press. p. 66. ISBN 9780520913806.

- Léry, Jean de (1993). History of a Voyage to the Land of Brazil. University of California Press. p. 58. ISBN 9780520913806.

- Léry, Jean de (1993). History of a Voyage to the Land of Brazil. University of California Press. p. 65. ISBN 9780520913806.

- Léry, Jean de (1993). History of a Voyage to the Land of Brazil. University of California Press. p. 61. ISBN 9780520913806.

- Léry, Jean de (1993). History of a Voyage to the Land of Brazil. University of California Press. p. 64. ISBN 9780520913806.

- Léry, Jean de (1993). History of a Voyage to the Land of Brazil. University of California Press. p. 59. ISBN 9780520913806.

- Léry, Jean de (1993). History of a Voyage to the Land of Brazil. University of California Press. p. 158. ISBN 9780520913806.

- Léry, Jean de (1993). History of a Voyage to the Land of Brazi. University of California Press. p. 159. ISBN 9780520913806.

- Léry, Jean de (1993). History of a Voyage to the Land of Brazil. University of California Press. p. 161. ISBN 9780520913806.

- Léry, Jean de (1993). History of a Voyage to the Land of Brazil. University of California Press. p. 163. ISBN 9780520913806.

- Léry, Jean de (1993). History of a Voyage to the Land of Brazil. University of California Press. p. 164. ISBN 9780520913806.

- Léry, Jean de (1993). History of a Voyage to the Land of Brazil. University of California Press. p. 168. ISBN 9780520913806.

- Léry, Jean de (1993). History of a Voyage to the Land of Brazil. University of California Press. p. 166. ISBN 9780520913806.

- Léry, Jean de (1993). History of a Voyage to the Land of Brazil. University of California Press. p. 173. ISBN 9780520913806.

- Léry, Jean de (1993). History of a Voyage to the Land of Brazil. University of California Press. p. 175. ISBN 9780520913806.

- PEREIRA, ANTHONY; Pereyra, Anthony (1991). "Review of History of a Voyage to the Land of Brazil, Otherwise Called America, JEAN DE LÉRY". Canadian Journal of Latin American and Caribbean Studies. 16 (32): 119–122. JSTOR 41800685.

- da Cunha, Antonio Brito (1992). "Review of History of a Voyage to the Land of Brazil, Otherwise Called America". The Quarterly Review of Biology. 67 (1): 40–41. doi:10.1086/417449. JSTOR 2830894.

- Conley, Tom (April 1993). "Jean de Lery , Janet Whatley". Renaissance Quarterly. 46 (1): 217–219. doi:10.2307/3039179.

- Browning, Barbara; de Lery, Jean; Whatley, Janet (August 1991). "History of a Voyage to the Land of Brazil, Otherwise called America, Containing the Navigation and the Remarkable Things Seen on the Sea by the Author; the Behavior of Villegagnon in That Country; and the Customs and Strange Ways of Life of the American Savages; Together with the Description of Various Animals, Trees, Plants, and Other Singular Things Completely Unknown over Here". The Hispanic American Historical Review. 71 (3): 628. doi:10.2307/2515899.

- Meyer, Judith P.; Whatley, Janet (Winter 1991). "History of a Voyage to the Land of Brazil.N Jean de Lery". Sixteenth Century Journal. 22 (4): 880. doi:10.2307/2542462.