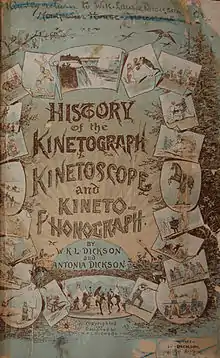

History of the Kinetograph, Kinetoscope, and Kinetophonograph

History of the Kinetograph, Kinetoscope, and Kinetophonograph is a book written by siblings William Kennedy Dickson and Antonia Dickson about the history of film. The brother Dickson wrote from his experiences working for Thomas Edison at his "Black Maria" studio in West Orange, New Jersey; Edison himself prefaced the book. Emphasis is placed on the eponymous devices: the kinetograph, the kinetoscope, and the kinetophonograph. Dickson helped to develop these devices, which facilitate the capturing and exhibition of motion pictures.

| |

| Author | |

|---|---|

| Illustrator | William Kennedy Dickson |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Genre | History |

| Published | 1895 |

| Publisher | Museum of Modern Art |

| Pages | 55 |

| OCLC | 82046841 |

Considered the first book of history on the subject of film, it was published in 1895 as a monograph. The Museum of Modern Art acquired the book in 1940 and later reprinted it in 1970 and 2000. The book has been received positively by literary critics and film scholars, who saw it as a valuable primary source and early look at the film industry.

Conception and contents

History of the Kinetograph, Kinetoscope, and Kinetophonograph is a collection of essays on the history of film, written by the motion picture pioneer William Kennedy Dickson and his sister, science writer Antonia Dickson.[1] The Dicksons had lived in England before moving to the United States in 1879. In 1883, at age 23, the brother Dickson earned the employment of Thomas Edison at his Machine Works company in New York City.[2] In 1888, Edison commissioned Dickson for the development of what would become the kinetoscope, an early means of playing back motion picture film.[3] Dickson moved later to Edison's "Black Maria" film production studio in West Orange, New Jersey; the bulk of History recounts his experiences working at this studio.[4]

The 55-page monograph contains 54 illustrations rendered by William.[1] The mechanics of primordial motion picture cameras and exhibition are explained,[4] with eponymous emphasis given to the kinetograph, the kinetoscope, and the kinetophonograph. Dickson worked with Edison on the development of these devices, which respectively capture pictures on film, play films back, and combine picture with sound.[5] Antonia and William give credit to the other architects of film and their works, as well as the performers and subjects who star in those works.[4] A preface penned by Edison appears at the book's start.[1]

Reception

History was published first in 1895.[4] An early version of the book's contents appeared in the June 1894 issue of The Century Magazine.[3] That year, the siblings had published a biography of Edison.[6] For the time of its publishing, the book served as not only a history of film but also as advertisement and a directory pertaining to the subjects in the films addressed in it.[7] The book fell out of knowledge since until the Museum of Modern Art acquired a copy in 1940. The museum's Film Library division gave it a reprinting thirty years later, in 1970; Arno Press published this reprinting in association with the New York Times Company.[lower-alpha 1][4] The book received another reprinting in 2000, this time published by the museum itself.[lower-alpha 2][1]

The book is considered by scholars of the medium the first published history on the subject of film,[8] with the art critic Nancy Mowll Mathews calling it unprecedented.[9] The historian Lewis Jacobs called the book important as a primary source for the history of early film. From the authors' combined tone, Jacobs perceived the Dicksons' excitement at having the privilege to observe popular film actors and to have worked in his industry at its infancy.[4] Jacobs defined the book as "intimate" and its closing words as an "eloquent prediction" on the expansion of kinetograph technology.[10] Jacobs recommended the book for film scholars and historians for its wisdom and its emphasis on the beginning of film as both a technology and as an art form.[11] The literary critic Laura Marcus found the book's scientific approach in tension with its purpose to market but conceded that the eponymous devices had a psychic nature intrinsically.[7] Marcus noted the harmony of the Dicksons' view of film as both uncanny and natural and of their opinion of the "Black Maria" as both a nursery and a laboratory like that depicted in Frankenstein.[12] Despite the book's promotional tone, Marcus called its imagery and motifs influential in shaping subsequent publications about film.[13]

Stéphanie Côté of the Journal of Film Preservation recommended the book for its importance as well but noted the difficulty of the brother Dickson's writing. Côté called the sister Dickson's style similarly flamboyant.[5] The film critic David Thomson regarded the book's prose as "plummy" from the brother Dickson's admiration for the film industry.[14] Mathews called Dickson's front cover illustration mediocre but convincing.[9]

Notes

- The book was included in the publisher's Literature of Cinema series (Côté 2001, p. 88).

- The museum captured William's illustrations using the duotone printing process (Anonymous 2002).

Citations

- Anonymous 2002.

- Dickson 1895, p. 55.

- Marcus 2010, p. 45.

- Jacobs 1971, p. 78.

- Côté 2001, p. 89.

- Marcus 2010, p. 53.

- Marcus 2010, p. 46.

- Bawden 1976, p. 193; Côté 2001, p. 88.

- Mathews 2005, p. 148.

- Jacobs 1971, pp. 78–79.

- Jacobs 1971, p. 79.

- Marcus 2010, pp. 46–47.

- Marcus 2010, p. 52.

- Thomson 2001, p. 43.

References

- Anonymous (2002). "History of the Kinetograph, Kinetoscope and Kinetophonograph". Distributed Art Publishers. Archived from the original on November 17, 2002. Retrieved April 21, 2016.

- Bawden, Liz-Anne (ed.) (1976). The Oxford Companion to Film. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780192115416.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Côté, Stéphanie (April 2001). "History of the Kinetograph, Kinetoscope and Kinetophonograph". Journal of Film Preservation (in French). International Federation of Film Archives. 62: 88–89.

- Dickson, William Kennedy; Dickson, Antonia (1895). History of the Kinetograph, Kinetoscope and Kinetophonograph. Museum of Modern Art.

- Jacobs, Lewis (1971). "History of the Kinetograph, Kinetoscope, and Kinetophonograph". Film Comment. Film Society of Lincoln Center. 7 (4): 78–79.

- Marcus, Laura (2010). The Tenth Muse: Writing About Cinema in the Modernist Period. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780191615412.

- Mathews, Nancy Mowll (2005). "Art and Film: Interactions". In Mathews, Nancy Mowll; Musser, Charles; Braun, Marta (eds.). Moving Pictures: American Art and Early Film, 1880–1910. 1. Hudson Hills Press. pp. 145–158. ISBN 9781555952280.

- Thomson, David (2001). "History of the Kinetograph, Kinetoscope and Kinetophonograph". Artforum Bookforum. 8 (4): 41, 43.