Human

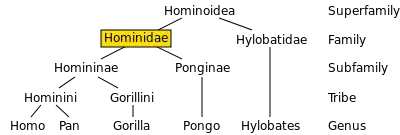

Humans (Homo sapiens) are a species of highly intelligent primates. They are the only extant members of the subtribe Hominina and—together with chimpanzees, gorillas, and orangutans—are part of the family Hominidae (the great apes, or hominids). Humans are terrestrial animals, characterized by their erect posture and bipedal locomotion; high manual dexterity and heavy tool use compared to other animals; open-ended and complex language use compared to other animal communications; larger, more complex brains than other primates; and highly advanced and organized societies.[3][4]

| Human[1] | |

|---|---|

| |

| An adult human male (left) and female (right) from the Akha tribe in Northern Thailand | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Primates |

| Suborder: | Haplorhini |

| Infraorder: | Simiiformes |

| Family: | Hominidae |

| Subfamily: | Homininae |

| Tribe: | Hominini |

| Genus: | Homo |

| Species: | H. sapiens |

| Binomial name | |

| Homo sapiens Linnaeus, 1758 | |

| Subspecies | |

| |

| |

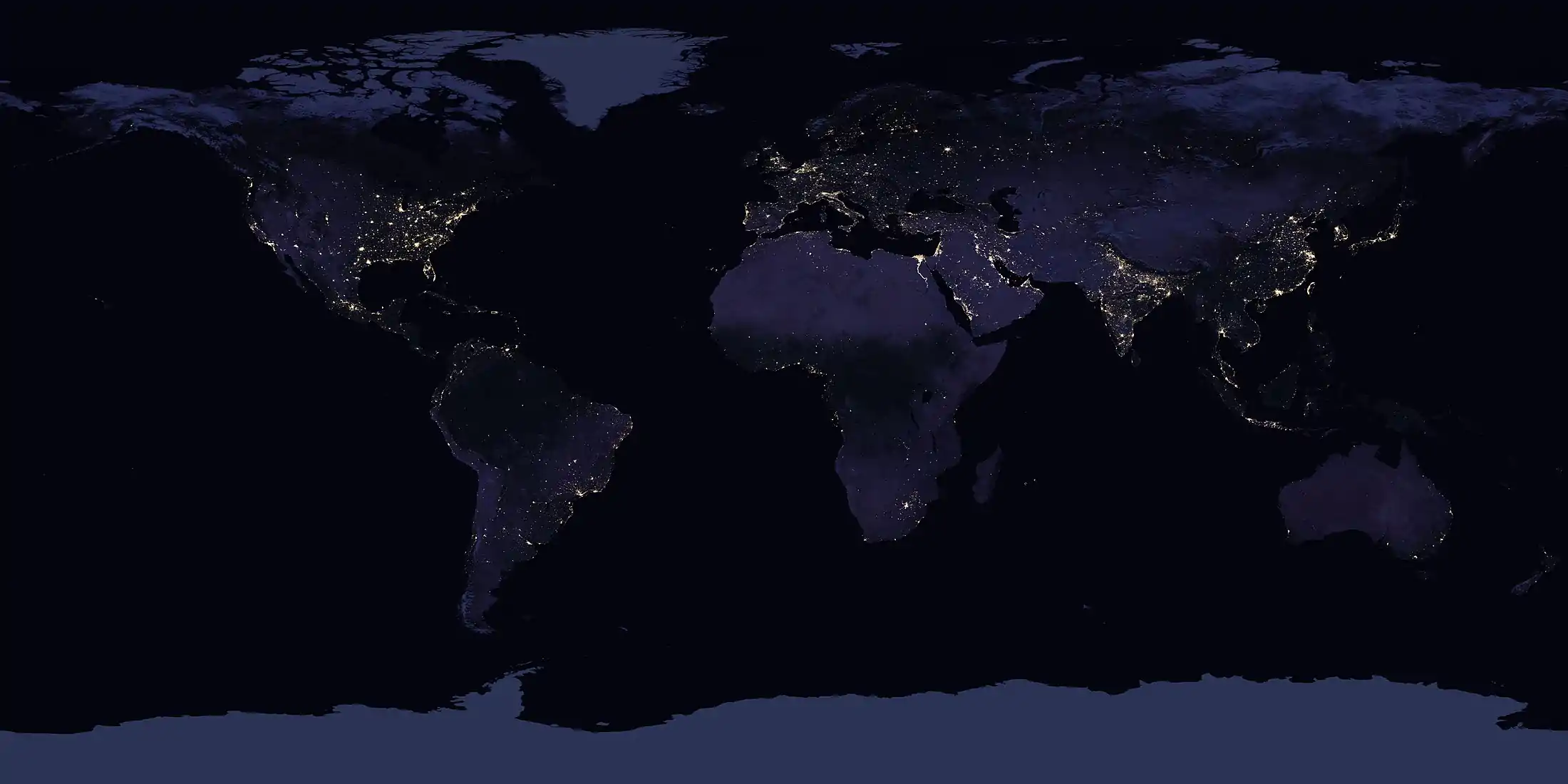

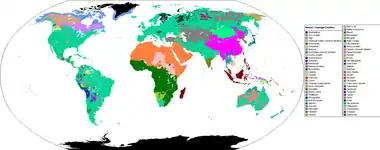

| Homo sapiens population density | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Species synonymy[1]

| |

Several early hominins used fire and occupied much of Eurasia. Early modern humans are thought to have diverged in Africa from an earlier hominin around 300,000 years ago, with the earliest fossil evidence of Homo sapiens also appearing around 300,000 years ago in Africa.[5] Humans began to exhibit evidence of behavioral modernity at least by about 150,000–75,000 years ago and possibly earlier.[6][7][8][9][10] In several waves of migration, H. sapiens ventured out of Africa and populated most of the world.[11][12] The spread of the large and increasing population of humans has profoundly affected the biosphere and millions of species worldwide. Among the key advantages that explain this evolutionary success is the presence of a larger, well-developed brain, which enables advanced abstract reasoning, language, problem solving, sociality, and culture through social learning. Humans use tools more frequently and effectively than any other animal: they are the only extant species to build fires, cook food, clothe themselves, and create and use numerous other technologies and arts.

Humans uniquely use systems of symbolic communication such as language and art to express themselves and exchange ideas, as well as to organize themselves into purposeful groups. Humans create complex social structures composed of many cooperating and competing groups, from families and kinship networks to political states. Social interactions between humans have established an extremely wide variety of values,[13] social norms, and rituals, which together undergird human society. Curiosity and the human desire to understand and influence the environment and to explain and manipulate phenomena have motivated humanity's development of science, philosophy, mythology, religion, and other fields of knowledge.

Though most of human existence has been sustained by hunting and gathering in band societies,[14] many human societies transitioned to sedentary agriculture approximately 10,000 years ago,[15] domesticating plants and animals, thus enabling the growth of civilization. These human societies subsequently expanded, establishing various forms of government and culture around the world, and unifying people within regions to form states and empires. The rapid advancement of scientific and medical understanding in the 19th and 20th centuries permitted the development of more efficient medical tools and healthier lifestyles, resulting in increased lifespans and causing the human population to rise exponentially.[16][17] The global human population is about 7.8 billion in 2021.[18][19]

Etymology and definition

Although it can be applied to other members of the genus Homo, in common usage the word "human" generally refers to the only extant species—Homo sapiens. The definition of H. sapiens itself is debated. Some paleoanthropologists include fossils that others have allocated to different species, while the majority assign only fossils that align anatomically with the species as it exists today.[20]

The English word "human" is a Middle English loanword from Old French humain, ultimately from Latin hūmānus, the adjectival form of homō ("man" - in the sense of humankind).[21] The native English term man can refer to the species generally (a synonym for humanity) as well as to human males. It may also refer to individuals of either sex, though this latter form is less common in contemporary English.[22]

The species binomial "Homo sapiens" was coined by Carl Linnaeus in his 18th-century work Systema Naturae.[23] The generic name "Homo" is a learned 18th-century derivation from Latin homō, which refers to humans of either sex.[24] The species name "sapiens" means "wise", "sapient", "knowledgeable" (Latin sapiens is the singular form, plural is sapientes).[25]

Evolution

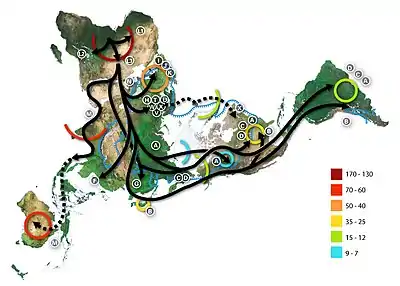

The genus Homo evolved and diverged from other hominins in Africa several million years ago, after the human clade split from the chimpanzee lineage of the hominids (great apes) branch of the primates.[26] Modern humans, specifically the subspecies Homo sapiens sapiens, proceeded to colonize all the continents and larger islands, arriving in Eurasia 125,000–60,000 years ago,[27][28] Australia around 65,000 years ago[29], the Americas around 15,000 years ago, and remote islands such as Hawaii, Easter Island, Madagascar, and New Zealand between the years 300 and 1280.[30][31]

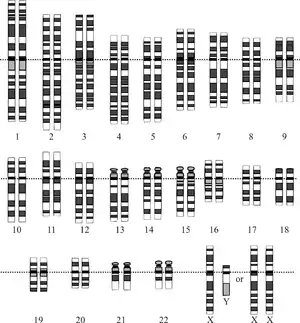

The closest living relatives of humans are chimpanzees and bonobos (genus Pan),[32][33] as well as gorillas (genus Gorilla).[34] The gibbons (family Hylobatidae) and orangutans (genus Pongo) were the first groups to split from the lineage leading to humans, then gorillas, and finally, chimpanzees. The splitting date between human and chimpanzee lineages is placed 4–8 million years ago, during the late Miocene epoch.[35][36] During this split, chromosome 2 was formed from the joining of two other chromosomes, leaving humans with only 23 pairs of chromosomes, compared to 24 for the other apes.[37]

The earliest fossils that have been proposed as members of the hominin lineage are Sahelanthropus tchadensis, dating from 7 million years ago; Orrorin tugenensis, dating from 5.7 million years ago; and Ardipithecus kadabba, dating to 5.6 million years ago. From these early species, the australopithecines arose around 4 million years ago, diverging into robust (Paranthropus) and gracile (Australopithecus) branches,[38] possibly one of which—such as A. garhi, dating to 2.5 million years ago—is a direct ancestor of the genus Homo.[39]

The earliest members of Homo evolved around 2.8 million years ago.[40] H. habilis has been considered the first species for which there is clear evidence of the use of stone tools.[41] Nonetheless, the brains of H. habilis were about the same size as that of a chimpanzee, and their main adaptation was bipedalism. During the next million years a process of encephalization began, and with the arrival of Homo erectus in the fossil record, cranial capacity had doubled. H. erectus were the first of the hominina to leave Africa, between 1.3 to 1.8 million years ago. One population, also sometimes classified as a separate species Homo ergaster, stayed in Africa and evolved into Homo sapiens. It is believed that these species were the first to use fire and complex tools.

Although the narratives of human evolution are often contentious, several discoveries since 2010 show that human evolution should not be seen as a simple linear or branched progression, but a mix of related species.[42][43][44] In fact, genomic research has shown that hybridization between substantially diverged lineages is the rule, not the exception, in human evolution.[45] Furthermore, it is argued that hybridization was an essential creative force in the emergence of modern humans.[45]

The earliest transitional fossils between H. ergaster/erectus and archaic humans are from Africa, such as Homo rhodesiensis, but seemingly transitional forms have also been found in Dmanisi, Georgia. These descendants of H. erectus spread through Eurasia c. 500,000 years ago, evolving into H. antecessor, H. heidelbergensis and H. neanderthalensis. Fossils of anatomically modern humans that date from the Middle Paleolithic (about 200,000 years ago) include the Omo-Kibish I remains of Ethiopia[46][47][48] and the fossils of Herto Bouri, Ethiopia. Earlier remains now classified as early Homo sapiens, such as the Jebel Irhoud remains from Morocco and the Florisbad Skull from South Africa, have been dated to about 300,000 and 259,000 years old respectively.[49][5][50][51][52][53] Fossil records of archaic Homo sapiens from Skhul in Israel and Southern Europe begin around 90,000 years ago.[54]

Anatomical adaptations

Human evolution is characterized by a number of morphological, developmental, physiological, and behavioral changes that have taken place since the split between the last common ancestor of humans and chimpanzees. The most significant of these adaptations are 1. bipedalism, 2. increased brain size, 3. lengthened ontogeny (gestation and infancy), 4. decreased sexual dimorphism (neoteny). The relationship between all these changes is the subject of ongoing debate.[55] Other significant morphological changes included the evolution of a power and precision grip, a change first occurring in H. erectus.[56]

Bipedalism is the basic adaption of the hominin line, and it is considered the main cause behind a suite of skeletal changes shared by all bipedal hominins. The earliest bipedal hominin is considered to be either Sahelanthropus[57] or Orrorin, with Ardipithecus, a full bipedal,[58] coming somewhat later. The knuckle walkers, the gorilla and chimpanzee, diverged around the same time, and either Sahelanthropus or Orrorin may be humans' last shared ancestor with those animals. [59] The early bipedals eventually evolved into the australopithecines and later the genus Homo. [60] There are several theories of the adaptational value of bipedalism. It is possible that bipedalism was favored because it freed up the hands for reaching and carrying food, because it saved energy during locomotion, because it enabled long-distance running and hunting, or as a strategy for avoiding hyperthermia by reducing the surface exposed to direct sun. [61][62]

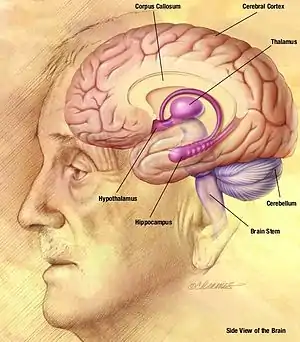

The human species developed a much larger brain than that of other primates—typically 1,330 cm3 (81 cu in) in modern humans, over twice the size of that of a chimpanzee or gorilla.[63] The pattern of encephalization started with Homo habilis which at approximately 600 cm3 (37 cu in) had a brain slightly larger than chimpanzees, and continued with Homo erectus (800–1,100 cm3 (49–67 cu in)), and reached a maximum in Neanderthals with an average size of 1,200–1,900 cm3 (73–116 cu in), larger even than Homo sapiens (but less encephalized).[64] The pattern of human postnatal brain growth differs from that of other apes (heterochrony), and allows for extended periods of social learning and language acquisition in juvenile humans. However, the differences between the structure of human brains and those of other apes may be even more significant than differences in size.[65][66][67][68] The increase in volume over time has affected different areas within the brain unequally—the temporal lobes, which contain centers for language processing have increased disproportionately, as has the prefrontal cortex which has been related to complex decision making and moderating social behavior.[63] Encephalization has been tied to an increasing emphasis on meat in the diet,[69][70] or with the development of cooking,[71] and it has been proposed [72] that intelligence increased as a response to an increased necessity for solving social problems as human society became more complex.

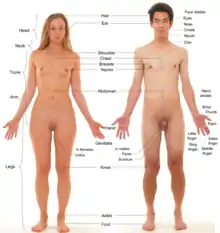

The reduced degree of sexual dimorphism is primarily visible in the reduction of the male canine tooth relative to other ape species (except gibbons). Another important physiological change related to sexuality in humans was the evolution of hidden estrus. Humans are the only ape in which the female is intermittently fertile year round, and in which no special signals of fertility are produced by the body (such as genital swelling during estrus). Nonetheless humans retain a degree of sexual dimorphism in the distribution of body hair and subcutaneous fat, and in the overall size, males being around 25% larger than females.

History

As early Homo sapiens dispersed, it encountered varieties of archaic humans both in Africa and in Eurasia, in Eurasia notably Homo neanderthalensis. Since 2010, evidence for gene flow between archaic and modern humans during the period of roughly 100,000 to 30,000 years ago has been discovered. This includes modern human admixture in Neanderthals, Neanderthal admixture in all modern humans outside Africa,[73][74] Denisova hominin admixture in Melanesians[75] as well as admixture from unnamed archaic humans to some Sub-Saharan African populations.[76]

The "out of Africa" migration of Homo sapiens took place in at least two waves, the first around 130,000 to 100,000 years ago, the second (Southern Dispersal) around 70,000 to 50,000 years ago,[77][78] resulting in the colonization of Australia around 65–50,000 years ago,[79][80][81] This recent out of Africa migration derived from East African populations, which had become separated from populations migrating to Southern, Central and Western Africa at least 100,000 years earlier.[82] Modern humans subsequently spread globally, replacing archaic humans (either through competition or hybridization). By the beginning of the Upper Paleolithic period (50,000 BP), and likely significantly earlier[8][9][6][7][10][83][84][85] behavioral modernity, including language, music and other cultural universals had developed.[86][87] They inhabited Eurasia and Oceania by 40,000 years ago, and the Americas at least 14,500 years ago.[88][89]

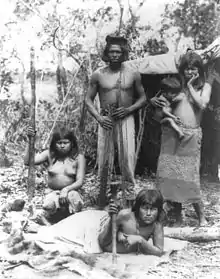

Until about 12,000 years ago (the beginning of the Holocene), all humans lived as hunter-gatherers, generally in small nomadic groups known as band societies, often in caves. The Neolithic Revolution (the invention of agriculture) took place beginning about 10,000 years ago, first in the Fertile Crescent, spreading through large parts of the Old World over the following millennia, and independently in Mesoamerica about 6,000 years ago. Access to food surplus led to the formation of permanent human settlements, the domestication of animals and the use of metal tools for the first time in history.

Agriculture and sedentary lifestyle led to the emergence of early civilizations (the development of urban development, complex society, social stratification and writing) from about 5,000 years ago (the Bronze Age), first beginning in Mesopotamia.[90] The Scientific Revolution, Technological Revolution and the Industrial Revolution brought such discoveries as imaging technology, major innovations in transport, such as the airplane and automobile; energy development, such as coal and electricity.[91] With the advent of the Information Age at the end of the 20th century, modern humans live in a world that has become increasingly globalized and interconnected. Human population growth and industrialisation has led to environmental destruction and pollution significantly contributing to the ongoing mass extinction of other forms of life called the Holocene extinction,[92] which may be further accelerated by global warming in the future.[93]

Habitat and population

| Population statistics | |

|---|---|

| World population[19] | 7.9 billion |

| Population density[19][94] | 15/km2 (40/sq mi) by total area 53/km2 (137/sq mi) by land area |

| Largest cities[95] | Tokyo, Delhi, Shanghai, Mumbai, São Paulo, Beijing, Mexico City, Osaka, Cairo, New York-Newark, Dhaka, Karachi, Buenos Aires, Kolkata, Istanbul, Chongqing, Lagos, Manila, Guangzhou, Rio de Janeiro, Los Angeles-Long Beach-Santa Ana, Moscow, Kinshasa, Tianjin, Paris, Shenzhen, Jakarta, Bangalore, London, Chennai, Lima |

Early human settlements were dependent on proximity to water and—depending on the lifestyle—other natural resources used for subsistence, such as populations of animal prey for hunting and arable land for growing crops and grazing livestock. Modern humans, however, have a great capacity for altering their habitats by means of technology, irrigation, urban planning, construction, deforestation and desertification.[96] Human settlements continue to be vulnerable to natural disasters, especially those placed in hazardous locations and with low quality of construction.[97] Deliberate habitat alteration is often done with the goals of increasing comfort or material wealth, increasing the amount of available food, improving aesthetics, or improving ease of access to resources or other human settlements. With the advent of large-scale trade and transport infrastructure, proximity to these resources has become unnecessary, and in many places, these factors are no longer a driving force behind the success of a population. Nonetheless, the manner in which a habitat is altered is often a major determinant in population change.

The human body's ability to adapt to different environmental stresses allows humans to acclimatize to a wide variety of temperatures, humidity, and altitudes. As a result, humans are a cosmopolitan species found in almost all regions of the world, including tropical rainforest, arid desert, extremely cold arctic regions, and heavily polluted cities. Most other species are confined to a few geographical areas by their limited adaptability.[98] The human population is not, however, uniformly distributed on the Earth's surface, because the population density varies from one region to another and there are large areas almost completely uninhabited, like Antarctica.[99][100] Most humans (61%) live in Asia; the remainder live in the Americas (14%), Africa (14%), Europe (11%), and Oceania (0.5%).[101]

Within the last century, humans have explored challenging environments such as Antarctica, the deep sea, and outer space. Human habitation within these hostile environments is restrictive and expensive, typically limited in duration, and restricted to scientific, military, or industrial expeditions. Human presence on other celestial bodies has been the case mainly with human-made robotic spacecraft[102][103][104] and with humans solely on the Moon, two at a time for brief intervals between 1969 and 1972. Long-term continuous human presence in space has been the case in orbit around Earth, uninterrupted since the initial crew of the International Space Station, arriving on 31 October 2000,[105] with peaks of thirteen humans at the same time in space.[106]

Since 1800, the human population has increased from one billion[107] to over seven billion.[108] The combined biomass of the carbon of all the humans on Earth in 2018 was estimated at 60 million tons, about 10 times larger than that of all non-domesticated mammals.[109]

In 2004, some 2.5 billion out of 6.3 billion people (39.7%) lived in urban areas.[110] Problems for humans living in cities include various forms of pollution and crime,[111] especially in inner city and suburban slums. Both overall population numbers and the proportion residing in cities are expected to increase significantly in the coming decades.[112]

Humans have had a dramatic effect on the environment. They are apex predators, being rarely preyed upon by other species.[113] Currently, through land development, combustion of fossil fuels, and pollution, humans are thought to be the main contributor to global climate change.[114] If this continues at its current rate, it is predicted that climate change will wipe out half of all plant and animal species over the next century.[115][116]

Biology

Anatomy and physiology

Most aspects of human physiology are closely homologous to corresponding aspects of animal physiology. The human body consists of the legs, the torso, the arms, the neck, and the head. An adult human body consists of about 100 trillion (1014) cells. The most commonly defined body systems in humans are the nervous, the cardiovascular, the circulatory, the digestive, the endocrine, the immune, the integumentary, the lymphatic, the musculoskeletal, the reproductive, the respiratory, and the urinary system.[117][118]

Humans, like most of the other apes, lack external tails, have several blood type systems, have opposable thumbs, and are sexually dimorphic. The comparatively minor anatomical differences between humans and chimpanzees are largely a result of human bipedalism and larger brain size. One difference is that humans have a far faster and more accurate throw than other animals. Humans are also among the best long-distance runners in the animal kingdom, but slower over short distances.[119][120] Humans' thinner body hair and more productive sweat glands help avoid heat exhaustion while running for long distances.[121]

As a consequence of bipedalism, human females have narrower birth canals. The construction of the human pelvis differs from other primates, as do the toes. A trade-off for these advantages of the modern human pelvis is that childbirth is more difficult and dangerous than in most mammals, especially given the larger head size of human babies compared to other primates. Human babies must turn around as they pass through the birth canal while other primates do not, which makes humans the only species where females usually require help from their conspecifics (other members of their own species) to reduce the risks of birthing. As a partial evolutionary solution, human fetuses are born less developed and more vulnerable. Chimpanzee babies are cognitively more developed than human babies until the age of six months, when the rapid development of human brains surpasses chimpanzees.

Apart from bipedalism, humans differ from chimpanzees mostly in smelling, hearing, digesting proteins, brain size, and the ability of language. Humans' brains are about three times bigger than in chimpanzees. More importantly, the brain to body ratio is much higher in humans than in chimpanzees, and humans have a significantly more developed cerebral cortex, with a larger number of neurons. The mental abilities of humans are remarkable compared to other apes. Humans' ability of speech is unique among primates. Humans are able to create new and complex ideas, and to develop technology, which is unprecedented among other organisms on Earth.[120]

It is estimated that the worldwide average height for an adult human male is about 171 cm (5 ft 7 in), while the worldwide average height for adult human females is about 159 cm (5 ft 3 in).[122] Shrinkage of stature may begin in middle age in some individuals, but tends to be typical in the extremely aged.[123] Through history human populations have universally become taller, probably as a consequence of better nutrition, healthcare, and living conditions.[124] The average mass of an adult human is 59 kg (130 lb) for females and 77 kg (170 lb) for males.[125][126] Like many other conditions, body weight and body type is influenced by both genetic susceptibility and environment and varies greatly among individuals. (see obesity)[127][128]

Humans have a density of hair follicles comparable to other apes. However, human body hair is vellus hair, most of which is so short and wispy as to be practically invisible. In contrast (and unusually among species), a follicle of terminal hair on the human scalp can grow for many years before falling out.[129][130] Humans have about 2 million sweat glands spread over their entire bodies, many more than chimpanzees, whose sweat glands are scarce and are mainly located on the palm of the hand and on the soles of the feet.[131] Humans have the largest number of eccrine sweat glands among species.

The dental formula of humans is: 2.1.2.32.1.2.3. Humans have proportionately shorter palates and much smaller teeth than other primates. They are the only primates to have short, relatively flush canine teeth. Humans have characteristically crowded teeth, with gaps from lost teeth usually closing up quickly in young individuals. Humans are gradually losing their third molars, with some individuals having them congenitally absent.[132]

Genetics

Like most animals, humans are a diploid eukaryotic species. Each somatic cell has two sets of 23 chromosomes, each set received from one parent; gametes have only one set of chromosomes, which is a mixture of the two parental sets. Among the 23 pairs of chromosomes there are 22 pairs of autosomes and one pair of sex chromosomes. Like other mammals, humans have an XY sex-determination system, so that females have the sex chromosomes XX and males have XY.[133]

No two humans—not even monozygotic twins—are genetically identical. Genes and environment influence human biological variation in visible characteristics, physiology, disease susceptibility and mental abilities. The exact influence of genes and environment on certain traits is not well understood.[134][135] Compared to the great apes, human gene sequences—even among African populations—are remarkably homogeneous.[136] On average, genetic similarity between any two humans is 99.5%-99.9%.[137][138][139][140][141][142] There is about 2–3 times more genetic diversity within the wild chimpanzee population than in the entire human gene pool.[143][144][145]

A rough and incomplete human genome was assembled as an average of a number of humans in 2003, and currently efforts are being made to achieve a sample of the genetic diversity of the species (see International HapMap Project). By present estimates, humans have approximately 22,000 genes.[146] The variation in human DNA is very small compared to other species, possibly suggesting a population bottleneck during the Late Pleistocene (around 100,000 years ago), in which the human population was reduced to a small number of breeding pairs.[147][148] By comparing mitochondrial DNA, which is inherited only from the mother, geneticists have concluded that the last female common ancestor whose genetic marker is found in all modern humans, the so-called mitochondrial Eve, must have lived around 90,000 to 200,000 years ago.[149][150][151]

The forces of natural selection have continued to operate on human populations, with evidence that certain regions of the genome display directional selection in the past 15,000 years.[152]

Life cycle

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

As with other mammals, human reproduction takes place by internal fertilization via sexual intercourse. Typically the gestation period is 38 weeks (9 months). At this point, most modern cultures recognize the baby as a person entitled to the full protection of the law, though some jurisdictions extend various levels of personhood earlier to human fetuses while they remain in the uterus.

Compared with other species, human childbirth is dangerous. Painful labors lasting 24 hours or more are not uncommon and sometimes lead to the death of the mother, the child or both.[153] This is because of both the relatively large fetal head circumference and the mother's relatively narrow pelvis.[154][155] The chances of a successful labor increased significantly during the 20th century in wealthier countries with the advent of new medical technologies. In contrast, pregnancy and natural childbirth remain hazardous ordeals in developing regions of the world, with maternal death rates approximately 100 times greater than in developed countries.[156]

In developed countries, infants are typically 3–4 kg (7–9 lb) in weight and 50–60 cm (20–24 in) in height at birth.[157] However, low birth weight is common in developing countries, and contributes to the high levels of infant mortality in these regions.[158] Both the mother and the father provide care for human offspring, in contrast to other primates, where parental care is mostly restricted to mothers.[159] Helpless at birth, humans continue to grow for some years, typically reaching sexual maturity at 12 to 15 years of age. Females continue to develop physically until around the age of 18, whereas male development continues until around age 21.

The human life span can be split into a number of stages: infancy, childhood, adolescence, young adulthood, adulthood and old age. The lengths of these stages, however, have varied across cultures and time periods. Compared to other primates, humans experience an unusually rapid growth spurt during adolescence, where the body grows 25% in size. Chimpanzees, for example, grow only 14%, with no pronounced spurt.[160] The presence of the growth spurt is probably necessary to keep children physically small until they are psychologically mature.

Humans are one of the few species in which females undergo menopause and become infertile decades before the end of their lives. All species of non-human apes are capable of giving birth until death. It has been proposed that menopause increases a woman's overall reproductive success by allowing her to invest more time and resources in her existing offspring, and in turn their children (the grandmother hypothesis), rather than by continuing to bear children into old age.[161][162]

Evidence-based studies indicate that the life span of an individual depends on two major factors, genetics and lifestyle choices.[163] For various reasons, including biological/genetic causes,[164] women live on average about four years longer than men. As of 2018, the global average life expectancy at birth of a girl is estimated to be 74.9 years compared to 70.4 for a boy.[165][166] There are significant geographical variations in human life expectancy, mostly correlated with economic development—for example life expectancy at birth in Hong Kong is 87.6 years for girls and 81.8 for boys, while in Central African Republic, it is 55.0 years for girls and 50.6 for boys.</ref>[167][168] The developed world is generally aging, with the median age around 40 years. In the developing world the median age is between 15 and 20 years. While one in five Europeans is 60 years of age or older, only one in twenty Africans is 60 years of age or older.[169] The number of centenarians (humans of age 100 years or older) in the world was estimated by the United Nations at 210,000 in 2002.[170]

Diet

Humans are omnivorous, capable of consuming a wide variety of plant and animal material.[171][172] Human groups have adopted a range of diets from purely vegan to primarily carnivorous. In some cases, dietary restrictions in humans can lead to deficiency diseases; however, stable human groups have adapted to many dietary patterns through both genetic specialization and cultural conventions to use nutritionally balanced food sources.[173] The human diet is prominently reflected in human culture, and has led to the development of food science.

Until the development of agriculture approximately 10,000 years ago, Homo sapiens employed a hunter-gatherer method as their sole means of food collection. This involved combining stationary food sources (such as fruits, grains, tubers, and mushrooms, insect larvae and aquatic mollusks) with wild game, which must be hunted and killed in order to be consumed.[174] It has been proposed that humans have used fire to prepare and cook food since the time of Homo erectus.[175] Around ten thousand years ago, humans developed agriculture,[176] which substantially altered their diet. This change in diet may also have altered human biology; with the spread of dairy farming providing a new and rich source of food, leading to the evolution of the ability to digest lactose in some adults.[177][178] Agriculture led to increased populations, the development of cities, and because of increased population density, the wider spread of infectious diseases. The types of food consumed, and the way in which they are prepared, have varied widely by time, location, and culture.

In general, humans can survive for two to eight weeks without food, depending on stored body fat. Survival without water is usually limited to three or four days. About 36 million humans die every year from causes directly or indirectly related to starvation.[179] Childhood malnutrition is also common and contributes to the global burden of disease.[180] However global food distribution is not even, and obesity among some human populations has increased rapidly, leading to health complications and increased mortality in some developed, and a few developing countries. Worldwide over one billion people are obese,[181] while in the United States 35% of people are obese, leading to this being described as an "obesity epidemic."[182] Obesity is caused by consuming more calories than are expended, so excessive weight gain is usually caused by an energy-dense diet.[181]

Biological variation

There is biological variation in the human species—with traits such as blood type, genetic diseases, cranial features, facial features, organ systems, eye color, hair color and texture, height and build, and skin color varying across the globe. The typical height of an adult human is between 1.4 and 1.9 m (4 ft 7 in and 6 ft 3 in), although this varies significantly depending on sex, ethnic origin,[183][184] and family bloodlines. Body size is partly determined by genes and is also significantly influenced by environmental factors such as diet, exercise, and sleep patterns. Adult height for each sex in a particular ethnic group approximately follows a normal distribution.

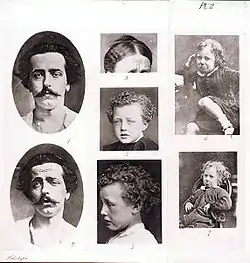

There is evidence that populations have adapted genetically to various external factors. The genes that allow adult humans to digest lactose are present in high frequencies in populations that have long histories of cattle domestication and are more dependent on cow milk. Sickle cell anemia, which may provide increased resistance to malaria, is frequent in populations where malaria is endemic. Similarly, populations that have for a long time inhabited specific climates, such as arctic or tropical regions or high altitudes, tend to have developed specific phenotypes that are beneficial for conserving energy in those environments—short stature and stocky build in cold regions, tall and lanky in hot regions, and with high lung capacities at high altitudes. Some populations have evolved highly unique adaptations to very specific environmental conditions, such as those advantageous to ocean-dwelling lifestyles and freediving in the Bajau.[185] Skin color tends to vary clinally and general correlates with the level of ultraviolet radiation in a particular geographic area, with darker skin mostly around the equator.[186][187][188][189]

Human skin color can range from darkest brown to lightest peach, or even nearly white or colorless in cases of albinism.[145] Human hair ranges in color from white to red to blond to brown to black, which is the most frequent.[190] Hair color depends on the amount of melanin, with concentrations fading with increased age, leading to grey or even white hair. Most researchers believe that skin darkening is an adaptation that evolved as protection against ultraviolet solar radiation. Light skin pigmentation protects against depletion of vitamin D, which requires sunlight to make.[191] Human skin also has a capacity to darken (tan) in response to exposure to ultraviolet radiation.[192][193][194]

There is relatively little variation between human geographical populations, and most of the variation that occurs is at the individual level.[145][195][196] Of the 0.1%-0.5% of human genetic differentiation, 85% exists within any randomly chosen local population. Genetic data shows that no matter how population groups are defined, two people from the same population group are almost as different from each other as two people from any two different population groups.[145][197][198][199]

Current genetic research has demonstrated that human populations native to the African continent are the most genetically diverse.[200] Human genetic diversity decreases in native populations with migratory distance from Africa, and this is thought to be the result of bottlenecks during human migration.[201][202] Humans have lived in Africa for the longest period of time, but only a part of Africa's population migrated out of the continent into Eurasia, bringing with them just a portion of the original African genetic variety. Non-African populations, however, acquired new genetic inputs from local admixture with archaic populations, and thus have much greater variation from Neanderthals and Denisovans than is found in Africa.[203] African populations also harbour the highest number of private genetic variants, or those not found in other places of the world. While many of the common variants found in populations outside of Africa are also found on the African continent, there are still large numbers which are private to these regions, especially Oceania and the Americas.[203] Furthermore, recent studies have found that populations in sub-Saharan Africa, and particularly West Africa, have ancestral genetic variation which predates modern humans and has been lost in most non-African populations. This ancestry is thought to originate from admixture with an unknown archaic hominin that diverged before the split of Neanderthals and modern humans.[204][205]

The greatest degree of genetic variation exists between males and females. While the nucleotide genetic variation of individuals of the same sex across global populations is no greater than 0.1%-0.5%, the genetic difference between males and females is between 1% and 2%. Males on average are 15% heavier and 15 cm (6 in) taller than females.[206][207] On average, men have about 40–50% more upper body strength and 20–30% more lower body strength than women.[208] Women generally have a higher body fat percentage than men. Women have lighter skin than men of the same population; this has been explained by a higher need for vitamin D in females during pregnancy and lactation. As there are chromosomal differences between females and males, some X and Y chromosome related conditions and disorders only affect either men or women. After allowing for body weight and volume, the male voice is usually an octave deeper than the female voice.[209] Women have a longer life span in almost every population around the world.[210]

Human variation is highly non-concordant: many of the genes do not cluster together and are not inherited together. Skin and hair color are mostly not correlated to height, weight, or athletic ability. Humans do not share the same patterns of variation through geography. Dark-skinned populations that are found in Africa, Australia, and South Asia are not closely related to each other.[194][211][212][213][214][215] Individuals with the same morphology do not necessarily cluster with each other by lineage, and a given lineage does not include only individuals with the same trait complex.[145][198][216] Due to practices of endogamy, allele frequencies cluster by geographic, national, ethnic, cultural and linguistic boundaries. Despite this, genetic boundaries around local populations do not biologically mark off any fully discrete groups of humans. Much of human variation is continuous, often with no clear points of demarcation.[216][217][218][211][219][220][221][222][223][224]

Psychology

The human brain, the focal point of the central nervous system in humans, controls the peripheral nervous system. In addition to controlling "lower," involuntary, or primarily autonomic activities such as respiration and digestion, it is also the locus of "higher" order functioning such as thought, reasoning, and abstraction.[225] These cognitive processes constitute the mind, and, along with their behavioral consequences, are studied in the field of psychology.

Humans have a larger and more developed prefrontal cortex than other primates, the region of the brain associated with higher cognition.[226] This has led humans to proclaim themselves to be more intelligent than any other known species.[227] Objectively defining intelligence is difficult, with other animals adapting senses and excelling in areas that humans are unable to.[228]

There are some traits that, although not strictly unique, do set humans apart from other animals.[229] Humans may be the only animals who have episodic memory and who can engage in "mental time travel".[230] Even compared with other social animals, humans have an unusually high degree of flexibility in their facial expressions.[231] Humans are the only animals known to cry emotional tears.[232] Humans are one of the few animals able to self-recognize in mirror tests[233] and there is also debate over what extent humans are the only animals with a theory of mind.[234]

Sleep and dreaming

Humans are generally diurnal. The average sleep requirement is between seven and nine hours per day for an adult and nine to ten hours per day for a child; elderly people usually sleep for six to seven hours. Having less sleep than this is common among humans, even though sleep deprivation can have negative health effects. A sustained restriction of adult sleep to four hours per day has been shown to correlate with changes in physiology and mental state, including reduced memory, fatigue, aggression, and bodily discomfort.[235]

During sleep humans dream, where they experience sensory images and sounds. Dreaming is stimulated by the pons and mostly occurs during the REM phase of sleep.[236] The length of a dream can vary, from a few seconds up to 30 minutes.[237] Humans have three to five dreams per night, and some may have up to seven;[238] however most dreams are immediately or quickly forgotten.[239] They are more likely to remember the dream if awakened during the REM phase. The events in dreams are generally outside the control of the dreamer, with the exception of lucid dreaming, where the dreamer is self-aware.[240] Dreams can at times make a creative thought occur or give a sense of inspiration.[241]

Consciousness and thought

Human consciousness, at its simplest, is "sentience or awareness of internal or external existence".[242] Despite centuries of analyses, definitions, explanations and debates by philosophers and scientists, consciousness remains puzzling and controversial,[243] being "at once the most familiar and most mysterious aspect of our lives".[244] The only widely agreed notion about the topic is the intuition that it exists.[245] Opinions differ about what exactly needs to be studied and explained as consciousness. Some philosophers divide consciousness into phenomenal consciousness, which is experience itself, and access consciousness, which is the processing of the things in experience.[246] It is sometimes synonymous with 'the mind', and at other times, an aspect of it. Historically it is associated with introspection, private thought, imagination and volition.[247] It now often includes some kind of experience, cognition, feeling or perception. It may be 'awareness', or 'awareness of awareness', or self-awareness.[248] There might be different levels or orders of consciousness,[249] or different kinds of consciousness, or just one kind with different features.[250]

The process of acquiring knowledge and understanding through thought, experience, and the senses is known as cognition.[251] The human brain perceives the external world through the senses, and each individual human is influenced greatly by his or her experiences, leading to subjective views of existence and the passage of time.[252] The nature of thought is central to psychology and related fields. Cognitive psychology studies cognition, the mental processes' underlying behavior.[253] Largely focusing on the development of the human mind through the life span, developmental psychology seeks to understand how people come to perceive, understand, and act within the world and how these processes change as they age.[254][255] This may focus on intellectual, cognitive, neural, social, or moral development. Psychologists have developed intelligence tests and the concept of intelligence quotient in order to assess the relative intelligence of human beings and study its distribution among population.[256]

Motivation and emotion

Human motivation is not yet wholly understood. From a psychological perspective, Maslow's hierarchy of needs is a well-established theory which can be defined as the process of satisfying certain needs in ascending order of complexity.[257] From a more general, philosophical perspective, human motivation can be defined as a commitment to, or withdrawal from, various goals requiring the application of human ability. Furthermore, incentive and preference are both factors, as are any perceived links between incentives and preferences. Volition may also be involved, in which case willpower is also a factor. Ideally, both motivation and volition ensure the selection, striving for, and realization of goals in an optimal manner, a function beginning in childhood and continuing throughout a lifetime in a process known as socialization.[258]

Emotions are biological states associated with the nervous system[259][260] brought on by neurophysiological changes variously associated with thoughts, feelings, behavioural responses, and a degree of pleasure or displeasure.[261][262] They are often intertwined with mood, temperament, personality, disposition, creativity,[263] and motivation. Emotion has a significant influence on human behavior and their ability to learn.[264] Acting on extreme or uncontrolled emotions can lead to social disorder and crime,[265] with studies showing criminals may have a lower emotional intelligence than normal.[266]

Emotional experiences perceived as pleasant, such as joy, interest or contentment, contrast with those perceived as unpleasant, like anxiety, sadness, anger, and despair.[267] Happiness, or the state of being happy, is a human emotional condition. The definition of happiness is a common philosophical topic. Some define as experiencing the feeling of positive emotionial affects, while avoiding the negative ones.[268] Others see it as an appraisal of life satisfaction, such as of quality of life.[269] Recent research suggests that being happy might involve experiencing some negative emotions when humans feel they are warranted.[270]

Sexuality and love

For humans, sexuality involves biological, erotic, physical, emotional, social, or spiritual feelings and behaviors.[271][272] Because it is a broad term, which has varied with historical contexts over time, it lacks a precise definition.[272] The biological and physical aspects of sexuality largely concern the human reproductive functions, including the human sexual response cycle.[271][272] Sexuality also affects and is affected by cultural, political, legal, philosophical, moral, ethical, and religious aspects of life.[271][272] Sexual desire, or libido, is a basic mental state present at the beginning of sexual behavior. Studies show that men desire sex more than women and masturbate more often.[273]

Humans can fall anywhere along a continuous scale of sexual orientation,[274] although most humans are heterosexual.[275][276] While homosexual behavior occurs in many other animals, only humans and domestic sheep have so far been found to exhibit exclusive preference for same-sex relationships.[275] Most evidence supports nonsocial, biological causes of sexual orientation,[275] as cultures that are very tolerant of homosexuality do not have significantly higher rates of it.[276][277] Research in neuroscience and genetics suggests that other aspects of human sexuality are biologically influenced as well.[278]

Love most commonly refers to a feeling of strong attraction or emotional attachment. It can be impersonal (the love of an object, ideal, or strong political or spiritual connection) or interpersonal (love between two humans).[279] Different forms of love have been described, including familial love (love for family), platonic love (love for friends), romantic love (sexual passion) and guest love (hospitality).[280] Romantic love has been shown to elicit brain responses similar to an addiction.[281] When in love dopamine, norepinephrine, serotonin and other chemicals stimulate the brain's pleasure center, leading to side effects such as increased heart rate, loss of appetite and sleep, and an intense feeling of excitement.[282]

Culture

| Human society statistics | |

|---|---|

| Most widely spoken native languages[283] | Chinese, Spanish, English, Hindi, Arabic, Portuguese, Bengali, Russian, Japanese, Javanese, German, Lahnda, Telugu, Marathi, Tamil, French, Vietnamese, Korean, Urdu, Italian, Indonesian, Persian, Turkish, Polish, Oriya, Burmese, Thai |

| Most practised religions[284] | Christianity, Islam, Hinduism, Buddhism, Sikhism, Judaism |

Humanity's unprecedented set of intellectual skills were a key factor in the species' eventual technological advancement and concomitant domination of the biosphere.[285] Disregarding extinct hominids, humans are the only animals known to teach generalizable information,[286] innately deploy recursive embedding to generate and communicate complex concepts,[287] engage in the "folk physics" required for competent tool design,[288][289] or cook food in the wild.[290] Teaching and learning preserves the cultural and ethnographic identity of all the diverse human societies.[291] Other traits and behaviors that are mostly unique to humans, include starting fires,[292] phoneme structuring[293] and vocal learning.[294]

The division of humans into male and female gender roles has been marked culturally by a corresponding division of norms, practices, dress, behavior, rights, duties, privileges, status, and power. Cultural differences by gender have often been believed to have arisen naturally out of a division of reproductive labor; the biological fact that women give birth led to their further cultural responsibility for nurturing and caring for children.[295] Gender roles have varied historically, and challenges to predominant gender norms have recurred in many societies.[296]

Language

While many species communicate, language is unique to humans, a defining feature of humanity, and a cultural universal.[297] Unlike the limited systems of other animals, human language is open—an infinite number of meanings can be produced by combining a limited number of symbols.[298][299] Human language also has the capacity of displacement, using words to represent things and happenings that are not presently or locally occurring, but reside in the shared imagination of interlocutors.[132]

Language differs from other forms of communication in that it is modality independent; the same meanings can be conveyed through different media, auditively in speech, visually by sign language or writing, and even through tactile media such as braille.[300] Language is central to the communication between humans, and to the sense of identity that unites nations, cultures and ethnic groups.[301] There are approximately six thousand different languages currently in use, including sign languages, and many thousands more that are extinct.[302]

Art

Art is a defining characteristics of humans and there is evidence for a relationship between creativity and language.[303] The earliest evidence of art was shell engravings made by Homo erectus 300,000 years before humans evolved.[304] Human art existed at least 75,000 years ago, with jewellery and drawings found in caves in South Africa.[305][306] There are various hypothesis's as to why humans have adapted to the arts. These include allowing them to better problem solve issues, providing a means to control or influence other humans, encouraging cooperation and contribution within a society or increasing the chance of attracting a potential mate.[307] The use of imagination developed through art, combined with logic may have given early humans an evolutionary advantage.[303]

Evidence of humans engaging in musical activities predates cave art and so far music has been practised by all human cultures.[308] There exists a wide variety of music genres and ethnic musics; with humans musical abilities being related to other abilities, including complex social human behaviours.[308] It has been shown that human brains respond to music by becoming synchronised with the rhythm and beat, a process called entrainment.[309] Dance is also a form of human expression found in all cultures[310] and may have evolved as a way to help early humans communicate.[311] Listening to music and observing dance stimulates the orbitofrontal cortex and other pleasure sensing areas of the brain.[312]

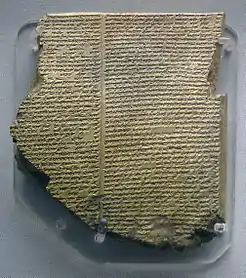

Unlike speaking, reading and writing does not come naturally to humans and must be taught.[313] Still literature has been present before the invention of words and language, with 30 000 year old paintings on walls inside some caves portraying a series of dramatic scenes.[314] One of the oldest surviving works of literature is the Epic of Gilgamesh, first engraved on ancient Babylonian tablets about 4,000 years ago.[315] Beyond simply passing down knowledge the use and sharing of imaginative fiction through stories might have helped develop humans capabilities for communication and increased the likelihood of securing a mate.[316] As well as entertainment, storytelling may also have been used as a way to provide the audience with moral lessons and encourage cooperation.[314]

Tools and technologies

Stone tools were used by proto-humans at least 2.5 million years ago.[317] The use and manufacture of tools has been put forward as the ability that defines humans more than anything else[318] and has historically been seen as an important evolutionary step.[319] The technology became much more sophisticated about 1.8 million years ago,[318] with the controlled use of fire beginning around 1 million years ago.[320][321] The development of more complex tools and technologies allowed land to be cultivated and animals to be domesticated, thus proving essential in the development of agriculture—what is known as the Neolithic Revolution.[322] Another wave of technological expansion brought about the Industrial Revolution, where the invention of automated machines brought major changes to humans lifestyles.[323] Throughout history, humans have altered their appearance by wearing clothing.[324] It has been suggested humans started wearing clothing when they migrated north away from Africa's warm climate.[325]

Religion and spirituality

Religion is generally defined as a belief system concerning the supernatural, sacred or divine, and practices, values, institutions and rituals associated with such belief. Some religions also have a moral code. The evolution and the history of the first religions have recently become areas of active scientific investigation.[326][327][328] While no other animals show religious behaviour, the empathy and imagination shown by chimpanzees could be a precursor to the evolution of human religion.[329] While the exact time when humans first became religious remains unknown, research shows credible evidence of religious behaviour from around the Middle Paleolithic era (45-200 thousand years ago).[330] It may have evolved to play a role in helping enforce and encourage cooperation between humans.[331]

There is no accepted academic definition of what constitutes religion.[332] Religion has taken on many forms that vary by culture and individual perspective in alignment with the geographic, social, and linguistic diversity of the planet.[332] Religion can include a belief in life after death (commonly involving belief in an afterlife),[333] the origin of life,[334] the nature of the universe (religious cosmology) and its ultimate fate (eschatology), and what is moral or immoral.[335] A common source for answers to these questions are beliefs in transcendent divine beings such as deities or a singular God, although not all religions are theistic.[336][337]

Although the exact level of religiosity can be hard to measure,[338] a majority of humans professes some variety of religious or spiritual belief.[339] In 2015 the majority were Christian followed by Muslims, Hindus and Buddhists,[340] although Islam is growing the most rapidly and likely to overtake Christianity by 2035.[341] In 2015 16% or slightly under 1.2 billion humans are irreligious. This includes humans who have no religious beliefs or do not identify with any religion.[341]

Science

An aspect unique to humans is their ability to transmit knowledge from one generation to the next and to continually build on this information to develop tools, scientific laws and other advances to pass on further.[342] This accumulated knowledge can be tested to answer questions or make predictions about how the universe functions and has been very successful in advancing human ascendancy.[343] Historians have identified two major scientific revolutions in human history. The first coincides with the Hellenistic period and the second with the Renaissance.[344] A chain of events and influences led to the development of the scientific method, a process of observation and experimentation that is used to differentiate science from pseudoscience.[345] An understanding of mathematics is unique to humans, although other species of animal have some numerical cognition.[346]

All of science can be divided into three major branches, the formal sciences (e.g., logic and mathematics), which are concerned with formal systems, the applied sciences (e.g., engineering, medicine), which are focused on practical applications, and the empirical sciences, which are based on empirical observation and are in turn divided into natural sciences (e.g., physics, chemistry, biology) and social sciences (e.g., psychology, economics, sociology).[347]

Philosophy

Philosophy is a field of study where humans seek to understand fundamental truths about themselves and the world in which they live.[348] Philosophical inquiry has been a major feature in the development of humans intellectual history.[349] It has been described as the "no man's land" between the definitive scientific knowledge and the dogmatic religious teachings.[350] Philosophy relies on reason and evidence unlike religion, but does not require the empirical observations and experiments provided by science.[351] Major fields of philosophy include metaphysics, epistemology, rationality, and axiology (which includes ethics and aesthetics).[352]

Society

Society is the system of organizations and institutions arising from interaction between humans. Humans are highly social beings and tend to live in large complex social groups. They can be divided into different groups according to their income, wealth, power, reputation and other factors.[353] The structure of social stratification and the degree of social mobility differs, especially between modern and traditional societies.[353] Human groups range from the size of families to nations. The first forms of human social organization were families living in band societies as hunter-gatherers.[354]

Kinship

All human societies organize, recognize and classify types of social relationships based on relations between parents, children and other descendants (consanguinity), and relations through marriage (affinity). There is also a third type applied to godparents or adoptive children (fictive). These culturally defined relationships are referred to as kinship. In many societies it is one of the most important social organizing principle and plays a role in transmitting status and inheritance.[355] All societies have rules of incest taboo, according to which marriage between certain kinds of kin relations are prohibited and some also have rules of preferential marriage with certain kin relations.[356]

Ethnicity

Human ethnic groups are a social category who identify together as a group based on shared attributes that distinguish them from other groups. These can be a common set of traditions, ancestry, language, history, society, culture, nation, religion, or social treatment within their residing area.[357][358] Ethnicity is separate from the concept of race, which is based on physical characteristics, although both are socially constructed.[359] Assigning ethnicity to certain population is complicated as even within common ethnic designations there can be a diverse range of subgroups and the makeup of these ethnic groups can change over time at both the collective and individual level.[360] Also there is no generally accepted definition on what constitutes an ethnic group.[361] Ethnic groupings can play a powerful role in the social identity and solidarity of ethno-political units. This has been closely tied to the rise of the nation state as the predominant form of political organization in the 19th and 20th centuries.[362][363][364]

Government and politics

The early distribution of political power was determined by the availability of fresh water, fertile soil, and temperate climate of different locations.[365] As farming populations gathered in larger and denser communities, interactions between these different groups increased. This led to the development of governance within and between the communities.[366] As communities got bigger the need for some form of governance increased, as all large societies without a government have struggled to function.[367] Humans have evolved the ability to change affiliation with various social groups relatively easily, including previously strong political alliances, if doing so is seen as providing personal advantages.[368] This cognitive flexibility allows individual humans to change their political ideologies, with those with higher flexibility less likely to support authoritarian and nationalistic stances.[369]

Governments create laws and policies that affect the citizens that they govern. There have been multiple forms of government throughout human history, each having various means of obtaining power and ability to exert diverse controls on the population.[370] As of 2017, more than half of all national governments are democracies, with 13% being autocracies and 28% containing elements of both.[371] Many countries have formed international political alliances, the largest being the United Nations with 193 member states.[372]

Trade and economics

Trade, the voluntary exchange of goods and services, is seen as a characteristic that differentiates humans from other animals and has been cited as a practice that gave Homo sapiens a major advantage over other hominids.[373][374] Evidence suggests early H. sapiens made use of long-distance trade routes to exchange goods and ideas, leading to cultural explosions and providing additional food sources when hunting was sparse, while such trade networks did not exist for the now extinct Neanderthals.[375][376] Early trade likely involved materials for creating tools like obsidian.[377] The first truly international trade routes were around the spice trade through the Roman and medieval periods.[378] Other important trade routes to develop around this time include the Silk Road, Incense Route, Amber road, Tea Horse Road, Salt Route, Trans-Saharan Trade Route and the Tin Route.[379]

Early human economies were more likely to be based around gift giving instead of a bartering system.[380] Early money consisted of commodities; the oldest being in the form of cattle and the most widely used being cowrie shells.[381] Money has since evolved into governmental issued coins, paper and electronic money.[381] Human study of economics is a social science that looks at how societies distribute scarce resources among different people.[382] There are massive inequalities in the division of wealth among humans; the eight richest humans are worth the same monetary value as the poorest half of all the human population.[383]

War

Humans willingness to kill other members of their species en masse though organised conflict has long been the subject of debate. One school of thought is that it has evolved as a means to eliminate competitors and has always been an innate human characteristic. The other suggests that war is a relatively recent phenomenon and appeared due to changing social conditions.[384] While not settled the current evidence suggests warlike predispositions only became common about 10,000 years ago, and in many places much more recently than that.[384] War has had a high cost on human life; it is estimated that during the 20th century, between 167 million and 188 million people died as a result of war.[385]

See also

References

- Groves, C. P. (2005). Wilson, D. E.; Reeder, D. M. (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0-801-88221-4. OCLC 62265494.

- Global Mammal Assessment Team (2008). "Homo sapiens". The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2008: e.T136584A4313662. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2008.RLTS.T136584A4313662.en. Archived from the original on 7 December 2017. Retrieved 12 May 2020.

- Goodman M, Tagle D, Fitch D, Bailey W, Czelusniak J, Koop B, Benson P, Slightom J (1990). "Primate evolution at the DNA level and a classification of hominoids". J Mol Evol. 30 (3): 260–66. Bibcode:1990JMolE..30..260G. doi:10.1007/BF02099995. PMID 2109087. S2CID 2112935.

- "Hominidae Classification". Animal Diversity Web @ UMich. Archived from the original on 5 October 2006. Retrieved 25 September 2006.

- Scerri, Eleanor M. L.; Thomas, Mark G.; Manica, Andrea; Gunz, Philipp; Stock, Jay T.; Stringer, Chris; Grove, Matt; Groucutt, Huw S.; Timmermann, Axel; Rightmire, G. Philip; d’Errico, Francesco (1 August 2018). "Did Our Species Evolve in Subdivided Populations across Africa, and Why Does It Matter?". Trends in Ecology & Evolution. 33 (8): 582–594. doi:10.1016/j.tree.2018.05.005. ISSN 0169-5347. PMC 6092560. PMID 30007846.

- Henshilwood, C. S.; d'Errico, F.; Yates, R.; Jacobs, Z.; Tribolo, C.; Duller, G. A. T.; Mercier, N.; Sealy, J. C.; Valladas, H.; Watts, I.; Wintle, A. G. (2002). "Emergence of modern human behavior: Middle Stone Age engravings from South Africa". Science. 295 (5558): 1278–1280. Bibcode:2002Sci...295.1278H. doi:10.1126/science.1067575. PMID 11786608. S2CID 31169551.

- Backwell, Lucinda; d'Errico, Francesco; Wadley, Lyn (2008). "Middle Stone Age bone tools from the Howiesons Poort layers, Sibudu Cave, South Africa". Journal of Archaeological Science. 35 (6): 1566–1580. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2007.11.006. ISSN 0305-4403.

- McBrearty, Sally; Brooks, Allison (2000). "The revolution that wasn't: a new interpretation of the origin of modern human behavior". Journal of Human Evolution. 39 (5): 453–563. doi:10.1006/jhev.2000.0435. PMID 11102266.

- Henshilwood, Christopher; Marean, Curtis (2003). "The Origin of Modern Human Behavior: Critique of the Models and Their Test Implications". Current Anthropology. 44 (5): 627–651. doi:10.1086/377665. PMID 14971366. S2CID 11081605.

- Brown, Kyle S.; Marean, Curtis W.; Herries, Andy I.R.; Jacobs, Zenobia; Tribolo, Chantal; Braun, David; Roberts, David L.; Meyer, Michael C.; Bernatchez, J. (14 August 2009), "Fire as an Engineering Tool of Early Modern Humans", Science, 325 (5942): 859–862, Bibcode:2009Sci...325..859B, doi:10.1126/science.1175028, PMID 19679810, S2CID 43916405

- McHenry, H.M (2009). "Human Evolution". In Michael Ruse; Joseph Travis (eds.). Evolution: The First Four Billion Years. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. p. 265. ISBN 978-0-674-03175-3.

- Neubauer, Simon; Hublin, Jean-Jacques; Gunz, Philipp (1 January 2018). "The evolution of modern human brain shape". Science Advances. 4 (1): eaao5961. Bibcode:2018SciA....4.5961N. doi:10.1126/sciadv.aao5961. ISSN 2375-2548. PMC 5783678. PMID 29376123.

- Marshall T. Poe A History of Communications: Media and Society from the Evolution of Speech to the Internet. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011. ISBN 978-0-521-17944-7

- "Hunting and gathering culture" Archived 16 January 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Encyclopædia Britannica (online). Encyclopædia Britannica Inc., 2016.

- "Neolithic Archived 17 July 2017 at the Wayback Machine." Ancient History Encyclopedia. Ancient History Encyclopedia Limited. 2014.

- "Will We Live Longer in the Future?". Retrieved 16 November 2020.

- Hamilton, Ian-Stuart (2 January 2013). "Why We Live Longer These Days, and Why You Should Worry". Psychology Today. Retrieved 16 November 2020.

- http://www.census.gov/popclock/. Retrieved 3 December 2020.

- "File POP/1-1: Total population (both sexes combined) by major area, region and country, annually for 1950-2100: Medium fertility variant, 2015–2100". World Population Prospects, the 2015 Revision. United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division, Population Estimates and Projections Section. July 2015. Archived from the original on 28 July 2016. Retrieved 2 October 2016.

- "Homo sapiens | Meaning & Stages of Human Evolution". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 18 September 2020.

- OED, s.v. "human."

- Merriam-Webster Dictionary, Man, "Definition 2" Archived 22 September 2017 at the Wayback Machine, accessed 14 September 2017

- Spamer, Earle E (29 January 1999). "Know Thyself: Responsible Science and the Lectotype of Homo sapiens Linnaeus, 1758". Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences. 149 (1): 109–14. JSTOR 4065043.

- Porkorny (1959) s.v. "g'hðem" pp. 414–16; "Homo." Dictionary.com Unabridged (v 1.1). Random House, Inc. 23 September 2008. "Homo". Dictionary.com. Archived from the original on 27 September 2008.

- "Homo sapiens Etymology". Online Etymology Dictionary. Archived from the original on 25 July 2015. Retrieved 25 July 2015.

- Tattersall Ian; Schwartz Jeffrey (2009). "Evolution of the Genus Homo". Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences. 37 (1): 67–92. Bibcode:2009AREPS..37...67T. doi:10.1146/annurev.earth.031208.100202.

- Armitage, S. J; Jasim, S. A; Marks, A. E; Parker, A. G; Usik, V. I; Uerpmann, H.-P (2011). "Hints of Earlier Human Exit From Africa". Science. 331 (6016): 453–56. Bibcode:2011Sci...331..453A. doi:10.1126/science.1199113. PMID 21273486. S2CID 20296624. Archived from the original on 27 April 2011. Retrieved 1 May 2011.

- Paul Rincon Humans 'left Africa much earlier' Archived 9 August 2012 at the Wayback Machine BBC News, 27 January 2011

- Clarkson, Chris; Jacobs, Zenobia; Marwick, Ben; Fullagar, Richard; Wallis, Lynley; Smith, Mike; Roberts, Richard G.; Hayes, Elspeth; Lowe, Kelsey; Carah, Xavier; Florin, S. Anna (July 2017). "Human occupation of northern Australia by 65,000 years ago". Nature. 547 (7663): 306–310. doi:10.1038/nature22968. ISSN 1476-4687.

- Lowe, David J. (2008). "Polynesian settlement of New Zealand and the impacts of volcanism on early Maori society: an update" (PDF). University of Waikato. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 May 2010. Retrieved 29 April 2010.

- Appenzeller Tim (2012). "Human migrations: Eastern odyssey". Nature. 485 (7396): 24–26. Bibcode:2012Natur.485...24A. doi:10.1038/485024a. PMID 22552074.

- Diogo, R.; Molnar, J.; Wood, B. (4 April 2017). "Bonobo anatomy reveals stasis and mosaicism in chimpanzee evolution, and supports bonobos as the most appropriate extant model for the common ancestor of chimpanzees and humans". Scientific Reports. 7 (1): 608. Bibcode:2017NatSR...7..608D. doi:10.1038/s41598-017-00548-3. PMC 5428693. PMID 28377592.

- Prüfer, K.; Munch, K.; Hellmann, I. (13 June 2012). "The bonobo genome compared with the chimpanzee and human genomes". Nature. 486 (1): 527–531. Bibcode:2012Natur.486..527P. doi:10.1038/nature11128. PMC 3498939. PMID 22722832.

- Wood, Bernard; Richmond, Brian G. (2000). "Human evolution: taxonomy and paleobiology". Journal of Anatomy. 197 (1): 19–60. doi:10.1046/j.1469-7580.2000.19710019.x. PMC 1468107. PMID 10999270.

- Ruvolo M (1997). "Genetic Diversity in Hominoid Primates". Annual Review of Anthropology. 26: 515–40. doi:10.1146/annurev.anthro.26.1.515.

- Ruvolo, Maryellen (1997). "Molecular phylogeny of the hominoids: inferences from multiple independent DNA sequence data sets". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 14 (3): 248–65. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a025761. PMID 9066793.

- Human Chromosome 2 is a fusion of two ancestral chromosomes Archived 9 August 2011 at the Wayback Machine by Alec MacAndrew; accessed 18 May 2006.

- McHenry, Henry M.; Coffing, Katherine (2000). "Australopithecus to Homo: Transformations in Body and Mind". Annual Review of Anthropology. 29: 125–46. doi:10.1146/annurev.anthro.29.1.125.

- Villmoare, Brian; Kimbel, William H.; Seyoum, Chalachew; Campisano, Christopher J.; DiMaggio, Erin N.; Rowan, John; Braun, David R.; Arrowsmith, J. Ramón; Reed, Kaye E. (20 March 2015). "Early Homo at 2.8 Ma from Ledi-Geraru, Afar, Ethiopia". Science. 347 (6228): 1352–55. Bibcode:2015Sci...347.1352V. doi:10.1126/science.aaa1343. PMID 25739410.

- Ghosh, Pallab (4 March 2015). "'First human' discovered in Ethiopia". BBC News. Archived from the original on 4 March 2015.

- Harmand, Sonia; Lewis, Jason E.; Feibel, Craig S.; Lepre, Christopher J.; Prat, Sandrine; Lenoble, Arnaud; Boës, Xavier; Quinn, Rhonda L.; Brenet, Michel; Arroyo, Adrian; Taylor, Nicholas; Clément, Sophie; Daver, Guillaume; Brugal, Jean-Philip; Leakey, Louise; Mortlock, Richard A.; Wright, James D.; Lokorodi, Sammy; Kirwa, Christopher; Kent, Dennis V.; Roche, Hélène (2015). "3.3-million-year-old stone tools from Lomekwi 3, West Turkana, Kenya". Nature. 521 (7552): 310–15. Bibcode:2015Natur.521..310H. doi:10.1038/nature14464. PMID 25993961. S2CID 1207285.

- Reich, David; Green, Richard E.; Kircher, Martin; et al. (23 December 2010). "Genetic history of an archaic hominin group from Denisova Cave in Siberia". Nature. 468 (7327): 1053–1060. Bibcode:2010Natur.468.1053R. doi:10.1038/nature09710. hdl:10230/25596. ISSN 0028-0836. PMC 4306417. PMID 21179161.

- Human Hybrids. (PDF). Michael F. Hammer. Scientific American, May 2013.

- Yong, Ed (July 2011). "Mosaic humans, the hybrid species". New Scientist. 211 (2823): 34–38. Bibcode:2011NewSc.211...34Y. doi:10.1016/S0262-4079(11)61839-3.

- Rogers Ackermann, Rebecca; Mackay, Alex; Arnold, Michael L (October 2015). "The Hybrid Origin of "Modern" Humans". Evolutionary Biology. 43 (1): 1–11. doi:10.1007/s11692-015-9348-1. S2CID 14329491.

- Hammond, Ashley S.; Royer, Danielle F.; Fleagle, John G. (July 2017). "The Omo-Kibish I pelvis". Journal of Human Evolution. 108: 199–219. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2017.04.004. ISSN 1095-8606. PMID 28552208.

- Fleagle, John G.; Brown, Francis H.; McDougall, Ian (17 February 2005). "Stratigraphic placement and age of modern humans from Kibish, Ethiopia". Nature. 433 (7027): 733–736. Bibcode:2005Natur.433..733M. doi:10.1038/nature03258. ISSN 1476-4687. PMID 15716951. S2CID 1454595.

- López, Saioa; van Dorp, Lucy; Hellenthal, Garrett (21 April 2016). "Human Dispersal Out of Africa: A Lasting Debate". Evolutionary Bioinformatics Online. 11 (Suppl 2): 57–68. doi:10.4137/EBO.S33489. ISSN 1176-9343. PMC 4844272. PMID 27127403.

- Stringer, C. (2016). "The origin and evolution of Homo sapiens". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences. 371 (1698): 20150237. doi:10.1098/rstb.2015.0237. PMC 4920294. PMID 27298468.

- White, Tim D.; Asfaw, B.; DeGusta, D.; Gilbert, H.; Richards, G. D.; Suwa, G.; Howell, F. C. (2003). "Pleistocene Homo sapiens from Middle Awash, Ethiopia". Nature. 423 (6491): 742–47. Bibcode:2003Natur.423..742W. doi:10.1038/nature01669. PMID 12802332. S2CID 4432091.

- Callaway, Ewan (7 June 2017). "Oldest Homo sapiens fossil claim rewrites our species' history". Nature. doi:10.1038/nature.2017.22114. Retrieved 11 June 2017.

- Sample, Ian (7 June 2017). "Oldest Homo sapiens bones ever found shake foundations of the human story". The Guardian. Retrieved 7 June 2017.

- Hublin, Jean-Jacques; Ben-Ncer, Abdelouahed; Bailey, Shara E.; Freidline, Sarah E.; Neubauer, Simon; Skinner, Matthew M.; Bergmann, Inga; Le Cabec, Adeline; Benazzi, Stefano; Harvati, Katerina; Gunz, Philipp (2017). "New fossils from Jebel Irhoud, Morocco and the pan-African origin of Homo sapiens" (PDF). Nature. 546 (7657): 289–292. Bibcode:2017Natur.546..289H. doi:10.1038/nature22336. PMID 28593953.

- Trinkaus, E. (1993). "Femoral neck-shaft angles of the Qafzeh-Skhul early modern humans, and activity levels among immature near eastern Middle Paleolithic hominids". Journal of Human Evolution. 25 (5): 393–416. doi:10.1006/jhev.1993.1058. ISSN 0047-2484. Archived from the original on 4 September 2012.

- Boyd, Robert; Silk, Joan B. (2003). How Humans Evolved. New York City: Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-97854-4.

- Brues, Alice M.; Snow, Clyde C. (1965). Biennial Review of Anthropology 1965. 4. pp. 1–39. ISBN 978-0-8047-1746-5. Archived from the original on 16 April 2016.

- Brunet, Michel; Guy, Franck; Pilbeam, David; Mackaye, Hassane Taisso; Likius, Andossa; Ahounta, Djimdoumalbaye; Beauvilain, Alain; Blondel, Cécile; Bocherens, Hervé; Boisserie, Jean-Renaud; De Bonis, Louis; Coppens, Yves; Dejax, Jean; Denys, Christiane; Duringer, Philippe; Eisenmann, Véra; Fanone, Gongdibé; Fronty, Pierre; Geraads, Denis; Lehmann, Thomas; Lihoreau, Fabrice; Louchart, Antoine; Mahamat, Adoum; Merceron, Gildas; Mouchelin, Guy; Otero, Olga; Campomanes, Pablo Pelaez; De Leon, Marcia Ponce; Rage, Jean-Claude; Sapanet, Michel; Schuster, Mathieu; Sudre, Jean; Tassy, Pascal; Valentin, Xavier; Vignaud, Patrick; Viriot, Laurent; Zazzo, Antoine; Zollikofer, Christoph (2002). "A new hominid from the Upper Miocene of Chad, Central Africa". Nature. 418 (6894): 145–51. Bibcode:2002Natur.418..145B. doi:10.1038/nature00879. PMID 12110880. S2CID 1316969.

- White, Tim D.; Lovejoy, C. Owen; Asfaw, Berhane; Carlson, Joshua P.; Suwa, Gen (April 2015), "Neither chimpanzee nor human, Ardipithecus reveals the surprising ancestry of both", Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 112 (16): 4877–84, Bibcode:2015PNAS..112.4877W, doi:10.1073/pnas.1403659111, PMC 4413341, PMID 25901308.

- Su, Denise (2013). "The Earliest Hominins: Sahelanthropus, Orrorin, and Ardipithecus". Nature Education Knowledge. 4 (4). Retrieved 7 February 2021.

- Wayman, Erin (August 2012). "Becoming Human: The Evolution of Walking Upright". Smithsonian. Retrieved 7 February 2021.

- Sexton, Laura (August 2007). "Going Bipedal". Archaeology. Retrieved 7 February 2021.