Hurricane Babe

Hurricane Babe was the second named storm and the first to impact the United States during the below-average 1977 Atlantic hurricane season. Forming out of a tropical wave on September 3, Babe began as a subtropical cyclone in the eastern Gulf of Mexico. The storm gradually intensified as it tracked westward. On September 5, the storm turned north and acquired tropical characteristics. Later that day, Babe intensified into a hurricane and attained its peak strength with winds of 75 mph (120 km/h) and a barometric pressure of 995 mbar (hPa; 29.38 inHg). Several hours later, the hurricane made landfall in Louisiana and quickly weakened. By September 6, Babe had weakened to a tropical depression and later dissipated early on September 9 over North Carolina.

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS/NWS) | |

Tropical Storm Babe soon after moving inland on September 5 | |

| Formed | September 3, 1977 |

|---|---|

| Dissipated | September 9, 1977 |

| Highest winds | 1-minute sustained: 75 mph (120 km/h) |

| Lowest pressure | 995 mbar (hPa); 29.38 inHg |

| Fatalities | None reported |

| Damage | $13 million (1977 USD) |

| Areas affected | Florida, Louisiana, Alabama, Mississippi, Tennessee, Georgia, South Carolina, North Carolina and Virginia |

| Part of the 1977 Atlantic hurricane season | |

Hurricane Babe produced minimal impact throughout its path in the United States. The most significant impact occurred in Louisiana where the storm caused $10 million (1977 USD; $42.2 million 2021 USD) in damage, mainly from crop losses. An additional $3 million (1977 USD; $12.7 million 2021 USD) in losses resulted from tornadoes spawned by Babe. Heavy rainfall in North Carolina, peaking at 8.99 in (228 mm) triggered flash flooding but little damage. No fatalities resulted from the hurricane. Coincidentally, a typhoon, also named Babe, existed at exactly the same time as Hurricane Babe.

Meteorological history

Hurricane Babe originated from a tropical wave that exited the western coast of Africa on August 23. Tracking westward, the wave eventually entered the Gulf of Mexico on September 2. Upon entering the gulf, a surface circulation developed; however, convection associated with the system was not concentrated around the center. The newly formed system then interacted with an upper tropospheric cyclonic vortex situated near the Florida coastline. The following day, Convective banding features around the cyclone led to the National Hurricane Center (NHC) upgrading the system to Tropical Storm Babe.[1] Although classified a tropical storm, Babe was not fully tropical, it was later classified as a subtropical cyclone.[2] The forward motion of Babe had slowed significantly from when it was a wave[1] but maintained the westward direction.[2]

By September 4, the maximum winds were found closer to the center of circulation and the cyclone developed a warmer core, a main feature in tropical cyclones. An anticyclone also developed over Babe and later that day, the storm transitioned into a tropical cyclone.[1] By this time, Babe had turned nearly due north and was near hurricane-status.[2] Around this time, reconnaissance missions into the storm found a closed eyewall with an eye measuring roughly 23 mi (37 km) in diameter.[3] Another reconnaissance flight that day found sustained winds of 80 mph (130 km/h); however, these winds were located roughly 65 mi (100 km) from the center and considered to be unrepresentative of the storm's actual intensity.[1]

Early on September 5, reconnaissance found a central barometric pressure of 995 mbar (hPa; 29.38 inHg), the lowest recorded in relation to the storm.[3] Around this time, Babe also intensified into a hurricane, attaining maximum winds of 75 mph (120 km/h).[1] Later that day, Hurricane Babe made landfall near Cocodrie, Louisiana and quickly weakened to a tropical storm.[2] By landfall, the eye of Babe had contracted to roughly 14 mi (23 km).[3] On September 6, the storm had weakened to a tropical depression and was moving northeast into Mississippi. The system continued this movement for the following two days.[1][2] While crossing South Carolina, forecasters thought that the system would emerge into the Atlantic Ocean and regenerate into a tropical depression.[4] However, the remnants of Babe dissipated shortly before crossing into North Carolina early on September 9.[2]

Preparations

Upon the storm's formation on September 3, gale warnings were issued for areas along the north-central coast of the Gulf of Mexico. By September 5, hurricane warnings were posted for areas between Vermilion Bay to the mouth of the Mississippi River in Louisiana. These warnings were later discontinued as the system moved over land. Ahead of the storm, up to 30,000 residents in low-lying parts of the state moved inland.[1] However, press reports indicate that upwards of 45,000 residents had evacuated from coastal regions prior to the storm. In Grand Isle, roughly 200 civil defense workers stayed behind in the town hall after the cities 2,300 residents evacuated.[5] In Cameron Parish, roughly 8,000 residents evacuated inland.[6] Emergency shelters were set up throughout Louisiana to house evacuees during the storm.[7] As Hurricane Babe began to weaken over Louisiana, forecasters anticipated the formation of tornadoes and issued tornado watches for parts of Louisiana, Alabama, Mississippi, Georgia and Florida.[8]

Impact

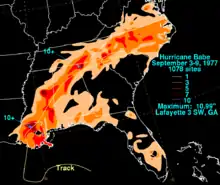

Prior to becoming a subtropical depression, Babe produced scattered rainfall in Florida, with peak amounts near 3 in (76 mm) falling around Lake Okeechobee. Widespread rain fell in relation to Babe throughout the Southern United States. In Louisiana, rain was confined to eastern parts of the state, with up to 10 in (250 mm) being measured near the Mississippi border. The remnants of the hurricane continued to produce heavy rain through its dissipation over North Carolina. A storm peak of 10.99 in (279 mm) fell in Lafayette, Georgia. Most of North Carolina received between 3 and 5 in (76 and 127 mm) of rain with isolated areas exceeding 7 in (180 mm).[9] A state maximum of 8.99 in (228 mm) fell in Lake Toxaway, North Carolina, 7.05 in (179 mm) in Caesars Head, South Carolina and 6.62 in (168 mm) in Chattanooga, Tennessee.[10]

Upon making landfall, Babe produced a storm surge of 5 ft (1.5 m), leading to minor coastal flooding.[1] Due to the storm's quick deterioration after moving inland, the NHC presumed that hurricane-force winds did not impact land. The highest wind gust was recorded in Grand Isle, Louisiana at 50 mph (85 km/h) and the highest sustained wind was recorded in Boothville, Louisiana at 45 mph (75 km/h).[1] In Jean Lafitte, Louisiana, overflow from the Fleming Canal produced flooding throughout the area.[11] The most significant damage was to croplands inundated by flood waters. Flash flooding occurred throughout the path of the former hurricane in the eastern United States, particularly in North Carolina.[1]

Hurricane Babe produced 14 tornadoes between September 5 and 7 along its track in several states.[12] Louisiana recorded the most, with six touchdowns,[13] including one F2 that injured one person and caused $2.5 million (1977 USD; $10.5 million 2021 USD) in damages near Hammond in Tangipahoa Parish.[8][14] A country store sustained severe damage from the tornado, with most of the back of the store destroyed. Six wood-frame homes were also knocked off their cinder block supports.[8] Another F2 touched down in Tuscaloosa County, Alabama; however, minimal damage was recorded along its 8 mi (13 km) track.[14] Another F2 briefly touched down in Harrison County, Mississippi on September 6.[14] It struck an unoccupied elementary school, wrecking six classrooms and leaving $500,000 (1977 USD; $2.11 million 2021 USD) in damages.[8] Throughout the storm's path, damages amounted to $10 million (1977 USD; $42.2 million 2021 USD)[1] with an additional $3 million (1977 USD; $12.7 million 2021 USD) from tornadoes.[13] There was no loss of life due to Babe.[1]

References

- Miles B. Lawrence (April 1978). "Atlantic Hurricane Season of 1977" (PDF). Monthly Weather Review. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. 106 (4): 534–545. Bibcode:1978MWRv..106..534L. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1978)106<0534:AHSO>2.0.CO;2. Retrieved April 17, 2013.

- National Hurricane Center (2009). "HURDAT: Easy-to-read version". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved August 29, 2009.

- Miles B. Lawrence and Paul J. Herbert (March 1979). "Annual Data and Verification Tabulation: Atlantic Tropical Cyclones in 1977" (PDF). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved August 29, 2009.

- Staff Writer (September 9, 1977). "Clara moves farther out to sea". Boca Raton News. Retrieved August 29, 2009.

- United Press International (September 6, 1977). "Twisters Born As Storm Dies". The Milwaukee Sentinel. Retrieved August 25, 2009.

- United Press International (September 5, 1977). "Hurricane Babe aims at Louisiana". St. Petersburg Times. Retrieved August 29, 2009.

- Staff Writer (September 4, 1977). "Hurricane Babe threatens coast". The Spokesman-Review. Retrieved August 29, 2009.

- Associated Press (September 6, 1977). "Hurricane Babe Sputters in La., Little Damage". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Retrieved August 25, 2009.

- David M. Roth (2009). "Hurricane Babe - September 3–9, 1977". Hydrometeorological Prediction Center. Retrieved August 29, 2009.

- Roth, David M; Hydrometeorological Prediction Center. "Tropical Cyclone Rainfall in the Southeastern United States". Tropical Cyclone Rainfall Point Maxima. United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's National Weather Service. Retrieved June 5, 2012.

- Associated Press (September 7, 1977). "Broom Against the Flood". The Ledger. Retrieved August 29, 2009.

- "List of Known Tropical Cyclones Which Have Spawned Tornadoes". Tornado History Project. 2009. Retrieved February 28, 2011.

- These figures are derived by adding totals documented in individual event reports. See Storm Data and Unusual Weather Phenomena (PDF). National Climatic Data Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 27, 2014. Retrieved February 27, 2014.

- Storm Data and Unusual Weather Phenomena (PDF). National Climatic Data Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 27, 2014. Retrieved February 27, 2014.