Hydroxyprogesterone acetate

Hydroxyprogesterone acetate (OHPA), sold under the brand name Prodox, is an orally active progestin related to hydroxyprogesterone caproate (OHPC) which has been used in clinical and veterinary medicine.[1][2][3][4][5][6][7][8] It has reportedly also been used in birth control pills.[9]

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Prodrox |

| Other names | OHPA; 17α-Hydroxyprogesterone acetate; 17α-Acetoxyprogesterone; Acetoxyprogesterone; 17α-Hydroxypregn-4-ene-3,20-dione 17α-acetate; 17α-Acetoxypregn-4-ene-3,20-dione |

| Routes of administration | By mouth |

| Drug class | Progestogen; Progestin; Progestogen ester |

| ATC code | |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number |

|

| PubChem CID | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.005.564 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C23H32O4 |

| Molar mass | 372.505 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

OHPA is a progestin, or a synthetic progestogen, and hence is an agonist of the progesterone receptor, the biological target of progestogens like progesterone.

OHPA was discovered in 1953 and was introduced for medical use in 1956.[10][11][12]

Medical uses

OHPA has been used in the treatment of a variety of gynecological disorders, including secondary amenorrhea, functional uterine bleeding, infertility, habitual abortion, dysmenorrhea, and premenstrual syndrome.[3][13][14]

OHPA (100 mg) was reportedly marketed in combination with mestranol (80 μg) as a sequential combined birth control pill under the brand name Hormolidin.[9] The preparation was available in the early 1970s.[9] The firm that manufactured it, known as Gador, was based in Argentina.[9]

Available forms

Side effects

Pharmacology

Pharmacodynamics

OHPA is a progestogen and acts as an agonist of the progesterone receptor (PR), both PRA and PRB isoforms (IC50 = 16.8 nM and 12.6 nM, respectively).[15] It has more than 50-fold higher affinity for the PR isoforms than 17α-hydroxyprogesterone, a little less than half the affinity of progesterone, and slightly higher affinity than OHPC.[16] Additional studies have reported on the affinity of OHPA for the PR.[17][18][19][20][21]

OHPA is of relatively low potency as a progestogen, which may explain its relatively limited use.[22] It is 100-fold less potent than medroxyprogesterone acetate, 400-fold less potent than chlormadinone acetate, and 1,200-fold less potent than cyproterone acetate in animal assays.[22] In terms of producing full progestogenic changes on the endometrium in women, 75 to 100 mg/day oral OHPA is equivalent to 20 mg/day parenteral progesterone, and OHPA is at least twice as potent as oral ethisterone in such regards.[3] It is also reportedly more potent than OHPC.[15][23] OHPA has been found to be effective as an oral progestogen-only pill at a dosage of 30 mg/day.[24]

| Compound | hPR-A | hPR-B | rbPR | rbGR | rbER | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Progesterone | 100 | 100 | 100 | <1 | <1 | |||

| 17α-Hydroxyprogesterone | 1 | 1 | 3 | 1 | <1 | |||

| Hydroxyprogesterone caproate | 26 | 30 | 28 | 4 | <1 | |||

| Hydroxyprogesterone acetate | 38 | 46 | 115 | 3 | ? | |||

| Notes: Values are percentages (%). Reference ligands (100%) were progesterone for the PR, dexamethasone for the GR, and estradiol for the ER. Sources: See template. | ||||||||

Pharmacokinetics

OHPA has very low but nonetheless significant oral bioavailability and can be taken by mouth.[25] The pharmacokinetics of OHPA have been reviewed.[2]

A single intramuscular injection of 150 to 350 mg OHPA in microcrystalline aqueous suspension has been found to have a duration of action of 9 to 16 days in terms of clinical biological effect in the uterus in women.[26]

| Compound | Form | Dose for specific uses (mg)[lower-alpha 3] | DOA[lower-alpha 4] | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TFD[lower-alpha 5] | POICD[lower-alpha 6] | CICD[lower-alpha 7] | ||||

| Algestone acetophenide | Oil soln. | - | – | 75–150 | 14–32 d | |

| Gestonorone caproate | Oil soln. | 25–50 | – | – | 8–13 d | |

| Hydroxyprogest. acetate[lower-alpha 8] | Aq. susp. | 350 | – | – | 9–16 d | |

| Hydroxyprogest. caproate | Oil soln. | 250–500[lower-alpha 9] | – | 250–500 | 5–21 d | |

| Medroxyprog. acetate | Aq. susp. | 50–100 | 150 | 25 | 14–50+ d | |

| Megestrol acetate | Aq. susp. | - | – | 25 | >14 d | |

| Norethisterone enanthate | Oil soln. | 100–200 | 200 | 50 | 11–52 d | |

| Progesterone | Oil soln. | 200[lower-alpha 9] | – | – | 2–6 d | |

| Aq. soln. | ? | – | – | 1–2 d | ||

| Aq. susp. | 50–200 | – | – | 7–14 d | ||

|

Notes and sources:

| ||||||

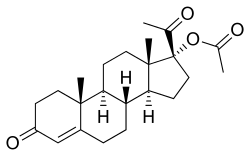

Chemistry

OHPA, also known as 17α-hydroxyprogesterone acetate or as 17α-acetoxypregn-4-ene-3,20-dione, is a synthetic pregnane steroid and a derivative of progesterone.[1][47] It is the acetate ester of 17α-hydroxyprogesterone, as well as a parent compound of a number of progestins including chlormadinone acetate, cyproterone acetate, medroxyprogesterone acetate, and megestrol acetate.[4][47]

Synthesis

Chemical syntheses of OHPA have been described.[2]

History

In 1949, it was discovered that 17α-methylprogesterone had twice the progestogenic activity of progesterone when administered parenterally,[48] and this finding led to renewed interest in 17α-substituted derivatives of progesterone as potential progestins.[12] Along with OHPC, OHPA was synthesized by Karl Junkmann of Schering AG in 1953 and was first reported by him in the medical literature in 1954.[10][11][49][50][12] OHPC shows very low oral activity[16] and was introduced for use via intramuscular injection by Squibb in 1956 under the brand name Delalutin.[12] Although a substantial prolongation of action occurs when OHPC is formulated in oil,[16] the same was not observed to a significant extent with OHPA, and this is likely why OHPC was chosen by Schering for development over OHPA.[7]

Subsequently, Upjohn unexpectedly discovered that OHPA, unlike OHPC and progesterone, is orally active and shows marked progestogenic activity with oral administration,[25] a finding that had been missed by the Schering researchers (who were primarily interested in the oil solubility of such esters).[7][12] OHPA was found to possess two to three times the oral activity of 17α-methylprogesterone.[51] Upjohn reported the oral activity of OHPA in the medical literature in 1957 and introduced the drug for medical use as Prodox in 25 mg and 50 mg oral tablet formulations later the same year.[3][12][13] OHPA was indicated for the treatment of a variety of gynecological disorders in women.[3][13][14] However, it saw relatively little use, which was perhaps due its comparatively low potency relative to a variety of other progestins such as medroxyprogesterone acetate and norethisterone.[22][14] These progestins were introduced around the same time and hence may have been favored.[22][14]

In 1960, OHPA was introduced also as Prodox as an oral progestin for veterinary use for the indication of estrus suppression in dogs.[8][52] However, probably due its high cost and the inconvenience of daily oral administration, the drug was not a market success.[8] It was superseded for this indication by medroxyprogesterone acetate (brand name Promone) in 1963, which could be administered by injection conveniently once every six months, although this preparation was discontinued in 1966 for various reasons and hence was not a market success either.[8]

Society and culture

Generic names

Hydroxyprogesterone acetate is the generic name of the drug and its INN.[1]

Brand names

OHPA is or was marketed under the brand name Prodox initially for clinical use and then for veterinary use.[1] Other brand names of OHPA include Gestageno, Gestageno Gador, Kyormon, Lutate-Inj, Prodix, and Prokan.[1] OHPA may also be or have been marketed in combination with estradiol enantate under the brand names Atrimon and Protegin in Argentina and Nicaragua.[53]

References

- J. Elks (14 November 2014). The Dictionary of Drugs: Chemical Data: Chemical Data, Structures and Bibliographies. Springer. pp. 664–. ISBN 978-1-4757-2085-3.

- Die Gestagene. Springer-Verlag. 27 November 2013. pp. 6, 278. ISBN 978-3-642-99941-3.

- DAVIS ME, WIED GL (1957). "17-alpha-HYDROXYPROGESTERONE acetate; an effective progestational substance on oral administration". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 17 (10): 1237–44. doi:10.1210/jcem-17-10-1237. PMID 13475464.

It is the purpose of this paper to introduce and describe a new steroid for oral administration, 17-a-hydroxyprogesterone acetate*, and to compare it with the most widely used oral substance with progestational properties, 20,21-anhydro-17-/3-hydroxyprogesterone. * Prodox, Upjohn Co., Kalamazoo, Michigan [...] It was found that 17-a-hydroxyprogesterone acetate has a progestational activity which is at least twice that of anhydrohydroxyprogesterone.

- Roger Lobo; P.G. Crosignani; Rodolfo Paoletti (31 October 2002). Women's Health and Menopause: New Strategies - Improved Quality of Life. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 91–. ISBN 978-1-4020-7149-2.

- James K. Stoller; Franklin A. Michota; Brian F. Mandell (2009). The Cleveland Clinic Foundation Intensive Review of Internal Medicine. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 13–. ISBN 978-0-7817-9079-6.

- Enrique Ravina (11 January 2011). The Evolution of Drug Discovery: From Traditional Medicines to Modern Drugs. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 194–. ISBN 978-3-527-32669-3.

- Walter Sneader (23 June 2005). Drug Discovery: A History. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 204–. ISBN 978-0-471-89979-2.

In 1954, Karl Junkmann of Schering AG reported that the acetylation of the 17-hydroxyl group of ethisterone provided a derivative suitable for formulating in oil for injection intramuscularly as a depot medication.79 There resulted widespread interest in preparing the acetates (and other esters) of various hydroxy-steroids. One such ester, Upjohn's 17-acetoxyprogesterone, provided to be a promising progestogen even though its hydroxy precursor was inactive. Unfortunately, it turned out that no significant prolongation of action was obtained by formulating it in oil. The Upjohn researchers, however, made the unexpected discovery that their acetoxy derivative was orally active, an observation that had been missed by the Schering group, who were primarily interested in the oil solubility of such esters.

- Upjohn Company (1978). Proceedings of the Symposium on Cheque® for Canine Estrus Prevention, Brook Lodge, Augusta, Michigan, March 13-15, 1978. Upjohn Company. p. 16.

[...] The first product was 17alpha-acetoxyprogesterone4 (Figure 1) marketed under the trade name of Prodox.® Prodox was introduced in 1960, was designed for oral use and was not a marketing success. The reasons are not clear as to lack of clear success, but one predominant reason was the high cost. For the average size dog, the cost of preventing estrus for a year was approximately $90. In addition, the inconvenience of daily oral administration may have prevented some market acceptance, especially at that cost. In 1963, Upjohn introduced injectable medroxyprogesterone acetate6 (Figure 1) under the trade name of Promone. Injections were to be made every six months, and this procedure was well accepted by both veterinarians and pet owners. However, Promone sales were discontinued in April, 1966 in the United States for basically two reasons. First was a prolonged and unpredictable return to estrus. This appeared to be due to very slow and variable absorption from the injection site. As a result of this variable absorption rate, one would expect a variable return to estrus. Even after [...]

- Harry W. Rudel; Fred A. Kinel (September 1972). "Oral Contraceptives. Human Fertility Studies and Side Effects". In M. Tausk (ed.). Pharmacology of the Endocrine System and Related Drugs: Progesterone, Progestational Drugs and Antifertility Agents. II. Pergamon Press. pp. 385–469. ISBN 978-0080168128. OCLC 278011135.

- M. Edward Davis (1930). M. Edward Davis Reprints. p. 406.

Chemically pure progesterone was the only substance with progestational properties in general use which could be administered parenterally until Junkmann (1) developed in 1953, 17-alpha-hydroxyprogesterone acetate and 17-alpha-hydroxyprogesterone caproate.

- WIED GL, DAVIS ME (1958). "Comparative activity of progestational agents on the human endometrium and vaginal epithelium of surgical castrates". Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 71 (5): 599–616. Bibcode:1958NYASA..71..599W. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.1958.tb46791.x. PMID 13583817.

In the group of new parenteral progestational agents, three substances developed by Karl Junkmann1,2 are the most outstanding and interesting: 17a-hydroxyprogesterone caproate and 17a-hydroxyprogesterone acetate, introduced in 1953, and the most potent of all new parenteral progestational agents, 17-ethynyl-19-nortestosterone enanthate, introduced in 1956.

- Norman Applezweig (1962). Steroid Drugs. Blakiston Division, McGraw-Hill. pp. 101–102.

Junkmann of Schering, AG., however, was able to show that long chain esters of 17a-hydroxyprogesterones such as the 17a-caproate produced powerful long-acting progestational effect. [...] Subsequently, a series of events led to the exploitation of 17a-hydroxyprogesterone derivatives as highly effective and orally active progestogens. Groups at Upjohn, Merck & Co., and Syntex independently found means of readily acetylating the 17-hydroxy group. Later, Upjohn announced it found that 17a-acetoxyprogesterone was orally active in humans and subsequently marketed this compound under the name of Prodox.

- Medical Digest. Medical Digest. Incorporated. 1958.

Prodox Tablets ( Upjohn) A new derivative of progesterone for oral administration. Indications: Secondary amenorrhea, functional uterine bleeding, in- fertility, habitual abortion, dysmen-orrhea and premenstrual tension. Supplied: Tablets containing 25 mg. or 50 mg. of hydroxyprogesterone a c e t a te, in bottles of 25 tablets.

- GREENBLATT RB (1959). "Hormonal control of functional uterine bleeding". Clinical Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2 (1): 232–46. doi:10.1097/00003081-195903000-00021. PMID 13639329.

[...] ethisterone, 25 mg. (Lutocylol; Pranone) 17-acetoxyprogesterone, 25 mg. (Prodox), 6-methyl-17-acetoxyprogesterone, 5 mg. (Provera), norethindrone, 5 mg. (Norlutin), norethinodrel, 5 mg. (Enovid). [...]

- Attardi BJ, Zeleznik A, Simhan H, Chiao JP, Mattison DR, Caritis SN (2007). "Comparison of progesterone and glucocorticoid receptor binding and stimulation of gene expression by progesterone, 17-alpha hydroxyprogesterone caproate, and related progestins". American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 197 (6): 599.e1–7. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2007.05.024. PMC 2278032. PMID 18060946.

- Shaik, Imam H.; Bastian, Jaime R.; Zhao, Yang; Caritis, Steve N.; Venkataramanan, Raman (2015). "Route of administration and formulation dependent pharmacokinetics of 17-hydroxyprogesterone caproate in rats". Xenobiotica. 46 (2): 169–174. doi:10.3109/00498254.2015.1057547. ISSN 0049-8254. PMC 4809632. PMID 26153441.

- Lontula K, Luukkainen JT, Vihko R (November 1973). "Progesterone-binding protein in human myometrium. Ligand specificity and some physicochemical characteristics". Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 328 (1): 145–53. doi:10.1016/0005-2795(73)90340-1. PMID 4357561.

- McGuire JL, Bariso CD, Shroff AP (January 1974). "Interaction between steroids and a uterine progestogen specific binding macromolecule". Biochemistry. 13 (2): 319–22. doi:10.1021/bi00699a014. PMID 4129556.

- Smith HE, Smith RG, Toft DO, Neergaard JR, Burrows EP, O'Malley BW (September 1974). "Binding of steroids to progesterone receptor proteins in chick oviduct and human uterus". J. Biol. Chem. 249 (18): 5924–32. PMID 4369808.

- Blanford AT, Wittman W, Stroupes SD, Westphal U (March 1978). "Steroid--protein interactions--XXXVIII. Influence of steroid structure on affinity to the progesterone-binding globulin". J. Steroid Biochem. 9 (3): 187–201. doi:10.1016/0022-4731(78)90149-8. PMID 77359.

- Wilks JW, Spilman CH, Campbell JA (June 1980). "Steroid binding specificity of the hamster uterine progesterone receptor". Steroids. 35 (6): 697–706. doi:10.1016/0039-128x(80)90094-x. PMID 7404605. S2CID 5895412.

- Benno Clemens Runnebaum; Thomas Rabe; Ludwig Kiesel (6 December 2012). Female Contraception: Update and Trends. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 133–134. ISBN 978-3-642-73790-9.

- Allan C. Barnes (1961). Progesterone. Brook Lodge Press. p. 28.

Hydroxyprogesterone cap- roate appears to be even less active than Prodox in some respects. It is about 5 times progesterone as an endometrial stimulator [...]

- M. Hamosh; A.S. Goldman (6 December 2012). Human Lactation 2: Maternal and Environmental Factors. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 454–. ISBN 978-1-4615-7207-7.

- Veterinary Medicine. 1959. p. 152.

Whereas progesterone is relatively inactive when administered orally, ethisterone (anhydrohydroxyprogesterone) and hydroxyprogesterone acetate are highly active.

- J. Ferin (September 1972). "Effects, Duration of Action and Metabolism in Man". In M. Tausk (ed.). Pharmacology of the Endocrine System and Related Drugs: Progesterone, Progestational Drugs and Antifertility Agents. II. Pergamon Press. pp. 13–24. ISBN 978-0080168128. OCLC 278011135.

- Knörr K, Beller FK, Lauritzen C (17 April 2013). Lehrbuch der Gynäkologie. Springer-Verlag. pp. 214–. ISBN 978-3-662-00942-0.

- Knörr K, Knörr-Gärtner H, Beller FK, Lauritzen C (8 March 2013). Geburtshilfe und Gynäkologie: Physiologie und Pathologie der Reproduktion. Springer-Verlag. pp. 583–. ISBN 978-3-642-95583-9.

- A. Labhart (6 December 2012). Clinical Endocrinology: Theory and Practice. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 554–. ISBN 978-3-642-96158-8.

- Horský J, Presl J (1981). "Hormonal Treatment of Disorders of the Menstrual Cycle". In Horsky J, Presl K (eds.). Ovarian Function and its Disorders: Diagnosis and Therapy. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 309–332. doi:10.1007/978-94-009-8195-9_11. ISBN 978-94-009-8195-9.

- Joachim Ufer (1969). The Principles and Practice of Hormone Therapy in Gynaecology and Obstetrics. de Gruyter. p. 49.

17α-Hydroxyprogesterone caproate is a depot progestogen which is entirely free of side actions. The dose required to induce secretory changes in primed endometrium is about 250 mg. per menstrual cycle.

- Willibald Pschyrembel (1968). Praktische Gynäkologie: für Studierende und Ärzte. Walter de Gruyter. pp. 598, 601. ISBN 978-3-11-150424-7.

- Ferin J (September 1972). "Effects, Duration of Action and Metabolism in Man". In Tausk M (ed.). Pharmacology of the Endocrine System and Related Drugs: Progesterone, Progestational Drugs and Antifertility Agents. II. Pergamon Press. pp. 13–24. ISBN 978-0080168128. OCLC 278011135.

- Henzl MR, Edwards JA (10 November 1999). "Pharmacology of Progestins: 17α-Hydroxyprogesterone Derivatives and Progestins of the First and Second Generation". In Sitruk-Ware R, Mishell DR (eds.). Progestins and Antiprogestins in Clinical Practice. Taylor & Francis. pp. 101–132. ISBN 978-0-8247-8291-7.

- Janet Brotherton (1976). Sex Hormone Pharmacology. Academic Press. p. 114. ISBN 978-0-12-137250-7.

- Sang GW (April 1994). "Pharmacodynamic effects of once-a-month combined injectable contraceptives". Contraception. 49 (4): 361–85. doi:10.1016/0010-7824(94)90033-7. PMID 8013220.

- Toppozada MK (April 1994). "Existing once-a-month combined injectable contraceptives". Contraception. 49 (4): 293–301. doi:10.1016/0010-7824(94)90029-9. PMID 8013216.

- Bagade O, Pawar V, Patel R, Patel B, Awasarkar V, Diwate S (2014). "Increasing use of long-acting reversible contraception: safe, reliable, and cost-effective birth control" (PDF). World J Pharm Pharm Sci. 3 (10): 364–392. ISSN 2278-4357. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-08-10. Retrieved 2016-08-24.

- Goebelsmann U (1986). "Pharmacokinetics of Contraceptive Steroids in Humans". In Gregoire AT, Blye RP (eds.). Contraceptive Steroids: Pharmacology and Safety. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 67–111. doi:10.1007/978-1-4613-2241-2_4. ISBN 978-1-4613-2241-2.

- Becker H, Düsterberg B, Klosterhalfen H (1980). "[Bioavailability of cyproterone acetate after oral and intramuscular application in men (author's transl)]" [Bioavailability of Cyproterone Acetate after Oral and Intramuscular Application in Men]. Urologia Internationalis. 35 (6): 381–5. doi:10.1159/000280353. PMID 6452729.

- Moltz L, Haase F, Schwartz U, Hammerstein J (May 1983). "[Treatment of virilized women with intramuscular administration of cyproterone acetate]" [Efficacy of Intra muscularly Applied Cyproterone Acetate in Hyperandrogenism]. Geburtshilfe Und Frauenheilkunde. 43 (5): 281–7. doi:10.1055/s-2008-1036893. PMID 6223851.

- Wright JC, Burgess DJ (29 January 2012). Long Acting Injections and Implants. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 114–. ISBN 978-1-4614-0554-2.

- Chu YH, Li Q, Zhao ZF (April 1986). "Pharmacokinetics of megestrol acetate in women receiving IM injection of estradiol-megestrol long-acting injectable contraceptive". The Chinese Journal of Clinical Pharmacology.

The results showed that after injection the concentration of plasma MA increased rapidly. The meantime of peak plasma MA level was 3rd day, there was a linear relationship between log of plasma MA concentration and time (day) after administration in all subjects, elimination phase half-life t1/2β = 14.35 ± 9.1 days.

- Runnebaum BC, Rabe T, Kiesel L (6 December 2012). Female Contraception: Update and Trends. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 429–. ISBN 978-3-642-73790-9.

- Artini PG, Genazzani AR, Petraglia F (11 December 2001). Advances in Gynecological Endocrinology. CRC Press. pp. 105–. ISBN 978-1-84214-071-0.

- King TL, Brucker MC, Kriebs JM, Fahey JO (21 October 2013). Varney's Midwifery. Jones & Bartlett Publishers. pp. 495–. ISBN 978-1-284-02542-2.

- Donna Shoupe (7 November 2007). The Handbook of Contraception: A Guide for Practical Management. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 103–. ISBN 978-1-59745-150-5.

- Plattner Pl A., Heusser H., Herzig P. Th (1949). "Uber steroide und sexualhormone. 159. Die synthese von 17-methyl-progesteron". Helvetica Chimica Acta. 32 (1): 270–275. doi:10.1002/hlca.19490320138. PMID 18115956.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- ACRH. U.S. Dept. of Energy. 1960. p. 71.

[The] minimal activity [of 17(a)-hydroxyprogesterone] is magnified to an unexpected degree by the esterification of this steroid with caproic acid to produce 17(a)-hydroxyprogesterone-17-n-caproate, first reported by Karl Junkmann in 1954.6,7

- Ralph Isadore Dorfman (1966). Methods in Hormone Research. Academic Press. p. 86.

Junkmann (1954) reported that the acetate, butyrate, and caproate forms had both increased and prolonged activity, [...]

- Raymond Eller Kirk; Donald Frederick Othmer; Herman Francis Mark (1965). Encyclopedia of chemical technology. Interscience Publishers. p. 78.

Subsequent acetylation with acetic anhydride and tosyl acid followed by Oppenauer oxidation afforded 17a-acetoxy- progesterone (95) in good yield (115). Tests showed this compound to possess 2-3 times the oral activity of 17-methylpregn-4-ene-3,20-dione (78) and to be many times more potent than progesterone (116,117).

- Pure-bred Dogs, American Kennel Gazette. American Kennel Club. 1961. p. 33.

According to Dr. Gordon G. Stocking, director of Upjohn's Veterinary Division, Prodox is a synthetic version of progesterone — one of the hormones that regulates the human female reproductive system. It is 100 per cent effective and has produced no ill-effects on 200 or more dogs on which it has been tested. As a result of its findings, says Dr. Stocking, Upjohn is making the product available through veterinarians.

- https://www.drugs.com/international/hydroxyprogesterone.html

- Index Nominum 2000: International Drug Directory. Taylor & Francis. 2000. pp. 532–. ISBN 978-3-88763-075-1.

- Sweetman, Sean C., ed. (2009). "Sex hormones and their modulators". Martindale: The Complete Drug Reference (36th ed.). London: Pharmaceutical Press. p. 2110. ISBN 978-0-85369-840-1.