Iris bismarckiana

Iris bismarckiana, the Nazareth iris, is a species in the genus Iris, it is also in the subgenus Iris and in the section Oncocyclus. It is a rhizomatous perennial, from the mountainsides of Israel, Lebanon, Jordan and Syria. It has stoloniferous, spreading rhizomes, long, sword shaped, bright green leaves, long slender stem (taller than the leaves) and 1 flower in Spring (between March and April). The large flower is pale yellow, creamy-white, or white background. Which is covered with reddish-brown, maroon brown, purple-brown, purple, blue-purple, or blue veins, markings or spots. It has a dark signal patch and dark purple to black beard. It is rarely cultivated as an ornamental plant in temperate regions (i.e. Europe or America), as it needs very dry conditions during the summer.

| Iris bismarckiana | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Monocots |

| Order: | Asparagales |

| Family: | Iridaceae |

| Genus: | Iris |

| Subgenus: | Iris subg. Iris |

| Section: | Iris sect. Oncocyclus |

| Species: | I. bismarckiana |

| Binomial name | |

| Iris bismarckiana | |

| Synonyms[2] | |

| |

Description

Iris bismarkiana is similar in growth to Iris susiana and Iris lortetii, (both also Oncocyclus Irises), they only differ in the colour of the flowers.[3]

It is a geophyte,[4][5][6] It has short,[7] stoloniferous rhizomes,[8][9] which are narrow, around 1.5 cm in diameter.[10] It forms long thin stolons, that can reach up to a few meters,[5] into the ground, seeking minerals. The rhizomes and stolons are very prone to viral diseases.[10] The creeping,[11][12] habit forms small clumps of plants.[10]

It has 6–8 leaves,[9] which are ensiform (sword-shaped),[7][10] glaucous,[11] and bright green.[5] They can grow up to between 30–50 cm (12–20 in) long,[9] and between 2–2.5 cm wide.[8][11] They form erect fans of leaves,[5][9] which are similar in form to I. susiana leaves.[11]

It has a long, slender stem,[6] or peduncle, that can grow up to between 30–50 cm (12–20 in) tall.[9][13][14] Although, some stems can reach 80 cm (31 in) tall.[15] The stem is usually taller than the leaves.[5]

The stem has a green, lanceolate, spathes (leaves of the flower bud), which is 7.6 cm (3 in) long.[7]

The stems holds 1 terminal (top of stem) flower,[7] blooming in spring,[8] between March and April.[5][16][17] In the UK, it flowered in May.[3]

The flowers are 10–15 cm (4–6 in) in diameter,[8][9][15] and they have a pale yellow,[9][11] yellow-green,[18] cream,[8] creamy-white,[11][12] or white ground.[13][19] Which is covered with reddish-brown,[15] maroon brown,[9][12][14] purple-brown,[5][7][10] purple,[7][19] blue-purple,[13][14] light violet,[6] lilac,[18] or blue veins or spots.[3][7][8]

Like other irises, it has 2 pairs of petals, 3 large sepals (outer petals), known as the 'falls' and 3 inner, smaller petals (or tepals), known as the 'standards'.[20] It has ovate shaped falls,[7][9][10] which are 6–7 cm (2–3 in) long and 4 cm wide.[7][9] They are densely spotted or veined and have a purple-brown,[7] or dark purple signal patch.[5][8][9] The signal is at the entrance to the perianth.[5] It is similar coloured to the spotting or veining.[7] In the middle of the falls, a row of short hairs called the 'beard', which is dark purple,[8][9][10] or blackish.[5][11] The standards are much paler (in colour) than the falls, and are orbicular (circular),[9] which are 7–9 cm (3–4 in) long.[9] They have paler veining or spotting as well,[11] in blue purple,[13] purple or blue.[8][9] The flowers are very similar in form to I. susiana.[10]

It has oblong shaped stigmas, which are a similar colour to the petals,[7] and are also densely veined.[10] It relies on a small number of pollinator species whose pollinators are specialists.[21]

After the iris has flowered, it produces a seed capsule, that opens up into three sections, to hold multiple seeds.[6][16]

Taxonomy

It is commonly known as Nazareth Iris,[5][6][16] due to being found on the mountains near Nazareth in Israel.[17] It is known in Arabic as 'Saoosan' (A-Natsir),[5] or سوسنة الناصره .[6] while in Hebrew, it is written as אִירוּס נָצְרָתִי .[4][6]

It is occasionally misspelt as Iris bismarkiana.[9][22]

The Latin specific epithet bismarckiana refers to Prince Otto von Bismark (1815-1898, 1st Chancellor of the German Empire).[23]

In 1888, rhizomes of the plant were sent from Lebanon to Germany, by Messrs. Dammann & Co., of Naples.[5][10][22] It was then described by E. Dammann and Carl Sprenger in Wiener Illustr. Gartzeitung (Wien. Gartenz.) Vol.352. fig. 72 in 1890 (with an illustration).[7][22][24] It was then widely published by Regel in Vol.17 of Wiener Illustr. Gartzeitung on page 855 in 1892.[25][26] In 1893, Foster described a new iris species, Iris sari var. nazarensis from the Nazareth area in Israel,[24] (in Gardener's Chronicle Vol. 33,[22]) but then in 1904, (in Botanical Magazine Vol.7986,[8]) Sprenger thought the two plants were the same. In 1934, John Edward Dinsmore published two species called Iris nazarena (from Nazareth) and Iris hermona (from the Golan Heights). Later, in 1970, Mouterde decided all the species were one type 'I. bismarckiana'. 'I. sari var. nazarensis' and 'I. nazarena' became synonyms of 'I. bismarckiana'. In 1972, Avishai disagreed, and thought that Iris hermona was a separate species, especially due to the rhizome differences (stoloniferous in 'I. bismarckiana' and compact in 'I. hermona'). Feinbrun-Dothan in 1986 agreed.[24] It is listed as 'I. bismarckiana' Damm. & Spreng ex Regel.[14]

It was verified by United States Department of Agriculture and the Agricultural Research Service on 10 March 1997, and then last changed on 1 December 2004.[25]

It is listed in the Encyclopedia of Life,[27] and in the Catalogue of Life.[28]

Distribution and habitat

It is native to south Lebanon and northern Israel.[30]

Range

It is found in Israel,[11][12][18] (including in the provinces of Upper and Lower Galilee,[4][5] on Mount Hermon,[6][13][14] on Mt. Yona,[5][6][10] and on Mount Tabor,[9]) Lebanon,[16][25][31] (on Mount Lebanon,[11] and in Wadi Rajib, near Adjloon,[7][1]) Syria,[8][9][26] and Jordan,[10][1] (on the Gilead Mountains).[4][24]

Habitat

It grows on the rocky and stony mountain-sides,[6][9][1] at the edges of woodlands,[5][6] or in scrub land.[9] It can be found on heavy, limestone clays,[12] basalt (rocks), or terra rossa and soft chalky rocks.[5][9][1] They can be found at an altitude of up to 1,300 m (4,300 ft) above sea level.[9]

Conservation

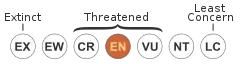

It is a very rare iris,[4] and was under risk of extinction,[32] from threats of urbanization, animal grazing and forestry (creating plantations) with in Israel.[5][19] In Lebanon, it was threatened by housing and road construction on its habitats.[31] It was listed by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), as Endangered when last assessed on 2 May 2016.[1]

Within Israel, the species is protected by law,[5][16] and it is grown in several nature reserves, including the Giv'at Ha-More Nature Reserve and in some of the smaller Reserves on Naphtali hill.[6] Although, it is still declining in populations in the reserves.[33]

In Upper Nazareth, Israel, a residential neighbourhood was planned, but it clashed with hundreds of irises. So a section of land was turned into a nature reserve to protect them.[34]

It is further threatened with the reserves, by an invasive weed, Sarcopoterium spinosum (or Prickly burnet), a common dwarf shrub which competes with the iris for space.[19][1][33] Although, it was found if the weed was burned in patches the iris grew stronger.[19][21] It is also threatened by caterpillars (who feed on the iris flower-buds).[33]

Cultivation

It is hardy to European Zone H4,[8] meaning hardy to −5 to −10 °C (or 23 to 14 °F).[35] It was cultivated in Naples, in 1888, but soon its growth suffered, due to the environmental conditions.[10] It is considered rather difficult to cultivate,[12] due to it needing high temperatures and dryness.[10] It is thought to be best planted in October, by William Rickatson Dykes.[3]

Propagation

Irises can generally be propagated by division,[36] or by seed growing. Irises generally require a period of cold, then a period of warmth and heat, also they need some moisture. Some seeds need stratification, (the cold treatment), which can be carried out indoors or outdoors. Seedlings are generally potted on (or transplanted) when they have 3 leaves.[37]

Hybrids and cultivars

Known I. bismarkiana cultivars include 'Benjaminii', 'Nazarena' and 'Nazarena Thompsoni'.[7]

Toxicity

Like many other irises, most parts of the plant are poisonous (rhizome and leaves), if mistakenly ingested can cause stomach pains and vomiting. Also handling the plant may cause a skin irritation or an allergic reaction.[38]

Uses

It is normally used as a garden ornamental plant, but they have also been planted in cemeteries,[5] including in Rajib.[1]

The iris rhizome has been used in a perfume called 'Iris Nazarena', by Aedes de Venustas,[39][40] a New York-based fragrance boutique.[41]

Culture

One source states that the iris was chosen, as the logo of The Society for the Protection of Nature in Israel,[17] but it is in fact Iris haynei (the Gilboa Iris).[34][42][43]

The 'Nazareth Iris' is known as the symbol of the city of Nof HaGalil.[32][34]

References

- Semaan, M.; Sapir, Y. "Iris bismarckiana". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Retrieved 1 September 2016.

- "Iris bismarckiana Damman & Sprenger is an accepted name". theplantlist.org (The Plant List). 23 March 2012. Retrieved 25 July 2016.

- Dykes, William (2009). "Handbook of Garden Irises" (PDF). beardlessiris.org (The Group for Beardless Irises). Retrieved 1 November 2014.

- Danin, Prof. Avinoam. "Iris bismarckiana Regel". flora.org.il (Flora of Israel Online). Retrieved 21 July 2016.

- "Iris bismarckiana Regel (1892)" (in Hebrew). redlist.parks.org (Based on the "Red Book – Endangered Plants of Israel" by Prof. Avi information, Dr. Gadi Pollack and Dr. Ori Fragman-Sapir). Retrieved 21 July 2016.

- "Iris bismarckiana". flowersinisrael.com. Retrieved 13 July 2016.

- Pries, Bob (15 July 2016). "(SPEC) Iris bismarckiana Damm. & Spreng". wiki.irises.org (American Iris Society). Retrieved 13 July 2016.

- James Cullen, Sabina G. Knees, H. Suzanne Cubey (Editors) The European Garden Flora Flowering Plants: A Manual for the Identification (2011) , p. 248, at Google Books

- British Iris Society (1997)A Guide to Species Irises: Their Identification and Cultivation, p. 73, at Google Books

- "Chapter I (Part 5) Oncocyclus II" (in French). irisbotanique.over-blog.com. Retrieved 25 July 2016.

- Weathers, John (1911). The Bulb Book; or Bulbous and tuberous plants for the open air, stove, and greenhouse, containing particulars as to descriptions, culture, propagation etc., of plants from all parts of the world having bulbs, corms, tubers, or rhizomes (orchids excluded). p. 297. Retrieved 29 June 2016.

- "Oncocyclus, Regelia and Reglio-cyclus Irises, The Plantsmen, Buckshaw Gardens, Holwell, Sherborne, Dorset" (PDF). srgc.net (Scottish Rock Garden Club). Retrieved 3 March 2016.

- Sadder, M. (14 April 2004). "Iris bismarckiana". signa.org (Species Iris Group of North America). Retrieved 13 July 2016.

- "Iris summary" (PDF). pacificbulbsociety.org. 14 April 2014. Retrieved 23 November 2014.

- Stebbings, Geoff (1997). The Gardener's Guide to Growing Irises. Newton Abbot: David and Charles. p. 69. ISBN 0715305395.

- "WILD IRIS – IRIS NAZARETH". pazzapazza2.blogspot.co.uk. 26 March 2016. Retrieved 20 July 2016.

- "Iris Nazareth – A Famous Israeli Flower". israelinsideout.com. Retrieved 20 July 2016.

- Cassidy, George E.; Linnegar, Sidney (1987). Growing Irises (Revised ed.). Bromley: Christopher Helm. p. 128. ISBN 0-88192-089-4.

- Siegel-Itzkovich, Judy (20 December 2006). "Technion: Save iris by killing weeds". jpost.com. Retrieved 26 July 2016.

- Austin, Claire (2005). Irises; A Garden Encyclopedia. Timber Press. ISBN 0881927309.

- Segal, Bosmat; Sapir, Yuval; Carmel, Yohay (January 2006). "Fragmentation and Pollination Crisis in the Self-Incompatible Iris Bismarckiana (Iridaceae), with Implications for Conservation". Israel Journal of Ecology and Evolution. Tel Aviv University. 52 (2): 111–122. doi:10.1560/IJEE_52_2_111. Retrieved 13 July 2016.

- Cohen, O.; Avisham, M. (2000). "The Irises still exist: The Conservation status of species Iris Section Oncocyclus in Israel, a century after their description". Annali di Botanica. 58. Retrieved 29 April 2016.

- Stearn, William (1973). A Gardenerer's Dictionary of Plant Names (Revised ed.). London: Cassell (published 1963). p. 60. ISBN 0304937215.

- Sapir, Yuval; Shmida, Avi; Comes, H. Peter (2001). "Iris bismarckiana in Israel and Jordan—New findings and taxonomic remarks" (PDF). Israel Journal of Plant Sciences. 49 (3): 229–236. doi:10.1560/FD4U-YWEK-XECA-N6GH. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 13 July 2016.

- "Iris bismarckiana". Germplasm Resources Information Network (GRIN). Agricultural Research Service (ARS), United States Department of Agriculture (USDA). Retrieved 21 July 2016.

- "Iridaceae Iris bismarckiana Regel". ipni.org (International Plant Names Index). Retrieved 25 July 2016.

- "Iris bismarckiana". eol.org. Retrieved 13 July 2016.

- "Iris bismarckiana". catalogueoflife.org. Retrieved 26 July 2016.

- "Iris bismarckiana". rhs.org.uk. Retrieved 13 July 2016.

- "Iris bismarckiana". World Checklist of Selected Plant Families. Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Retrieved 2018-01-12.

- "The natural site of El-Dichar". ehmej.org. Retrieved 25 March 2016.

- Rinat, Zafrir (9 July 2006). "Will Nazareth Protect the Nazareth Iris?". haaretz.com. Retrieved 25 July 2016.

- Segal, Bosmat; Carmel, Yohay; Kaplan, Didi; Dolev, Moti. "Nature Reserve Management for Conservation of the Endangered Species Iris bismarckiana". ecologylab.net.technion.ac.il. Retrieved 25 July 2016.

- Rinat, Zafrir (11 September 2006). "Caution, Iris Ahead!". haaretz.com. Retrieved 25 July 2016.

- "Plant Hardiness". theseedsite.co. Retrieved 3 August 2015.

- "How to divide iris rhizomes". gardenersworld.com. Retrieved 12 October 2015.

- Waters, Tom (December 2010). "Growing Irises from Seed". telp.com. Retrieved 28 April 2016.

- David G Spoerke and Susan C. SmolinskeToxicity of Houseplants, p. 236, at Google Books

- van der Post, Lucia. "Scents of the divine". howtospendit.ft.com. Retrieved 26 July 2016.

- "Iris Nazarena Aedes de Venustas for women and men". franganitca.com. Retrieved 28 July 2016.

- Andy (31 July 2013). "Aedes de Venustas Iris Nazarena : Perfume Review". boisdejasmin.com. Retrieved 28 July 2016.

- Alon TalAll the Trees of the Forest: Israel's Woodlands from the Bible to the Present, p. 260, at Google Books

- "Israel Environment Bulletin Autumn 1992–5753, Vol. 15, No. 4". mfa.gov.il. 21 December 1998. Retrieved 25 July 2016.

Sources

- Danin, A. Distribution atlas of plants in the Flora Palaestina area. 2004 (Atlas Palest)

- Mathew, B. The Iris. 1981 (Iris) 47.

- Mouterde, P. Nouvelle flore du Liban et de la Syrie. 1966– (F Liban)

- Sapir, Y. et al. 2002. Morphological variation of the Oncocyclus irises (Iris: Iridaceae) in the southern Levant Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 139:369–382.

- Zohary, M. & N. Feinbrun-Dothan Flora palaestina. 1966– (F Palest)

External links

- Various irises of Israel

- Listed as part of the Flora of Israel

- Picture of the iris and red Poppies in Israel

![]() Media related to Iris bismarckiana at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Iris bismarckiana at Wikimedia Commons

![]() Data related to Iris bismarckiana at Wikispecies

Data related to Iris bismarckiana at Wikispecies