Itō Jakuchū

Itō Jakuchū (伊藤 若冲, 2 March 1716 – 27 October 1800)[1] was a Japanese painter of the mid-Edo period when Japan had closed its doors to the outside world. Many of his paintings concern traditionally Japanese subjects, particularly chickens and other birds. Many of his otherwise traditional works display a great degree of experimentation with perspective, and with other very modern stylistic elements.

Itō Jakuchū | |

|---|---|

伊藤 若冲 | |

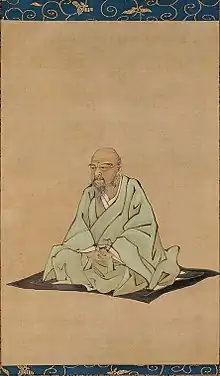

A portrait of Itō Jakuchū drawn by Kubota Beisen on the 85th anniversary of his death | |

| Born | March 2, 1716 |

| Died | October 27, 1800 (aged 84) |

| Nationality | Japanese |

| Known for | Painter |

Notable work | Pictures of the Colorful Realm of Living Beings |

Compared to Soga Shōhaku and other exemplars of the mid-Edo period eccentric painters, Jakuchū is said to have been very calm, restrained, and professional. He held strong ties to Zen Buddhist ideals, and was considered a lay brother (koji); but he was also keenly aware of his role within a Kyoto society that was becoming increasingly commercial.

Biography

Itō Jakuchū was the eldest son of Itō Genzaemon, a Kyoto grocer whose shop, called Masuya, lay in the center of downtown, in the Nishiki food district. Jakuchū ran the shop from the time of his father's death in 1739 until 1755, when he turned it over to one of his brothers.

His training in paintings was mostly derived from inspirations from nature and training under Kano school[2] and from examining Japanese and Chinese paintings at Zen temples. Some sources indicate that he may have studied with Ōoka Shunboku, an Osaka-based artist known for his bird and flower paintings. Though a number of his paintings depict exotic or fantastic creatures, such as tigers and phoenixes, it is evident from the detail and lifelike appearance of his paintings of chickens and other animals that he based his work on actual observation.

Jakuchū built a two-story studio on the west bank of the Kamo River in his late thirties. He called it Shin'en-kan (心遠館, Villa of the Detached Heart [or Mind]), after a phrase from a poem by the ancient Chinese poet Tao Qian. It was around this time that Jakuchū befriended Daiten Kenjō, a Rinzai monk who would later become abbot of the Kyoto temple Shōkoku-ji. Through this friendship Jakuchū gained access to the temple's large collection of Japanese and Chinese paintings, and gained introduction to new social and artistic circles. It is thought that Daiten may have been the one to first conceive of the name "Jakuchū", taken from the Tao Te Ching and meaning "like the void".

Well-known and well-reputed in the Kyoto art community, Jakuchū received many commissions for screen paintings, and was at one time featured above a number of other notable artists in the Record of Heian Notables (平安人物誌, Heian jinbutsu-shi). In addition to personal commissions, Jakuchū was also commissioned to paint panels or screens for many Buddhist temples and Shinto shrines across Japan, including the very famous and important Rokuon-ji (the monastery which includes the Kinkaku-ji Golden Pavilion on its grounds).

Despite his commercial successes, however, Jakuchū can definitely be said to have lived the life of a literary intellectual (bunjin). He was friends with many notable bunjin, went on journeys with them, and was influenced by their artistic styles. His own degree of experimentation was a result of a combination of this bunjin influence and his own personal creative drive. In addition to his experiments with Western materials and perspective, Jakuchū also employed on occasion a method called taku hanga (拓版画, "rubbing prints"). This method used woodblocks to resemble a Chinese technique of ink rubbings of inscribed stone slabs, and was employed by Jakuchū in a number of works, including a scroll entitled "Impromptu Pleasures Afloat" (乗興舟, Jōkyōshū), depicting his and his mentor, Daiten Kenjo's (大典顕常), journey down the Yodo River. The piece is currently residing in The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. Itō Jakuchū’s scroll was created using the technique of taku-hanga which allows the background of the scroll to be black while Daiten Kenjo's texts and the artist's details are presented in greys and whites.[3]

In the spring of 1767, both Daiten and Jakuchū decided to travel to Osaka via boat on the Yodo River, which connects Kyoto and Osaka. The 39-foot scroll, "Impromptu Pleasures Afloat" (乗興舟, Jōkyōshū), commemorates and illustrates the journey. The handscroll is the entire Yodo River from morning to night. The scroll contains short impromptu Chinese poems inscribed by Daiten inspired by the scenery seen on the journey, which mirrors how the river itself transported ideas. Daiten also includes the names of landmarks and other important areas of the Yodo River. Jakuchū seems to borrow stylistic elements and motifs from the "Eight Views of Xiaoxiang" (Chinese: 瀟湘八景; pinyin: Xiāoxiāng Bājǐng) like the evening sun, clear skies, white sails, a temple's evening bell, and finishing villages.[3]

Despite his individualism and involvement in the scholarly and artistic community of Kyoto, Jakuchū was always strongly religious, and retired towards the end of his life to Sekihō-ji, a Manpuku-ji branch temple on the southern outskirts of Kyoto. There, he gathered a number of followers, and continued to paint until his death at the age of eighty-five.

Works

A very common theme among his work is birds, in particular hens and roosters, though several of his more famous paintings depict cockatoos, parrots, and phoenixes.

One of his most ambitious endeavors, and therefore most famous works, is known as the "Pictures of the Colorful Realm of Living Beings" (動植綵絵, Dōshoku sai-e). Begun around 1757 and not finished until 1765, the Pictures are a set of twenty-seven hanging scrolls created as a personal offering to the Shōkoku-ji temple. In his deed of the gift, Jakuchu notes "in the hope that they will always be utilized as objects of solemn reference." They depict a number of animal subjects in monumental scale and with an according degree of detail. The paintings are composed using different colored pigments on silk. Today, Dōshoku sai-e is owned by the Museum of the Imperial Collections. Most of Itō Jakuchū's recovered paintings were ink on a hanging scroll, folding screens, or fusuma panels. However, later in his career, Itō Jakuchū would go on to enjoy painting on handscrolls.[3]

Another notable example of Jakuchū's handscrolls is his work "Compendium of Vegetables and Insects" (Saichufu). The 40-foot scroll is a painting of almost ninety different fruits and vegetables, fifty-some varieties of insects, and other animals. Some of which include: plums, peaches, apples, winter melon, daikon radish, onions, carrots, frogs, salamanders, butterflies, dragonflies, and bumblebees. The painting utilizes pigments and inks on silk with a grey scaled background. The painting is almost muted in color save for the bright oranges, yellows, and reds, and greens in the fruits and vegetables. Jakuchū's knowledge of produce from his family's grocer is evident within his scroll and the details in the said fruits and vegetables. The scroll starts with the depiction of the various fruits and vegetables in seasonal order, then moves to insects and animals with a single butterfly linking the two sides. It is speculated that Jakuchū's inspiration was from the significance of vegetables and fruits in Chinese art. The meaning of this painting may be linked to Jakuchū's link with the Buddhist faith which is also significantly present in another work of Jakuchū's, "Vegetable Parinirvana", parinirvana being defined as "nirvana-after-death, which occurs upon the death of someone who has attained nirvana during his or her lifetime". Jakuchū's portrays a Buddha's death using vegetables. The Buddha is "played" by a daikon radish surrounded by other mourning vegetables. Eggplants, turnips, and mushrooms are some of the ones included in his painting. The painting is supposed to mimic the typical traditional iconography of nirvana images which includes the eight sal trees (stalks of corn), lotus pedastal (woven basket), Queen Maya (quince fruit), and the orientation of the Buddha where his head is facing left (the daikon's leaves). Jakuchū's choice of the daikon radish as the Buddha has to do with the importance of daikon in Zen culture. Takuan Sōhō, an abbot in the Rinzai school of Zen Buddhism, was actually credited for his creation of the yellow pickled daikon radish, named after him. Historians remain unsure of the motivations behind Jakuchū's painting, but his choices in the painting prove to be meaninful and assert that the Buddha spirit is present everywhere even in vegetables. Some theorize it is to commemorate the death of his mother others say it is to commemorate the death of his brother.[3]

Another of his famous pieces, dubbed "Birds and Animals in the Flower Garden" (鳥獣花木図屏風, Chōjūkaboku-zu byōbu), is arguably one of the most modern-looking pieces to come out of Japan during this period. The piece, one of a pair of sixfold screens, depicts a white elephant and a number of other animals in a garden. What makes it unique, eccentric and modern is the division of the entire piece into a grid of squares (or, in modern terms, the painting is "pixelated") roughly a centimeter on each side. Each square was colored individually, in order to create the resulting aggregate image. Today, Chōjūkaboku-zu byōbu is owned by the Idemitsu Museum of Arts.[4]

Jakuchū also experimented with a number of forms of printing, most of them using woodblocks. But occasionally he would use stencils or other methods to produce different effects. Jakuchū's painting style is influenced by Shen Nanping (Shen Quan c. 1682–1760). His crane subjects prove this, being part of traditional Japanese legacy, but also the neutral background and the ‘cut’ given to the scene composition, with always a careful and detailed flora and fauna decorative style of painting.[5]

The Jakuchū gafu (若冲画譜 ; "Album of Jakuchū) is a series of works depicting flowers. The work is always in a circle, such as can be found on ceiling paintings. The originals were poorly preserved, but a number of quality copies of the album were made during the Meiji era of the 1890s.[6][7][8]

Nandina and Rooster. Part of the series Dōshoku sai-e

Nandina and Rooster. Part of the series Dōshoku sai-e Chrysanthemums by a stream, with rocks. Part of the series Dōshoku sai-e

Chrysanthemums by a stream, with rocks. Part of the series Dōshoku sai-e Roosters. Part of the series Dōshoku sai-e

Roosters. Part of the series Dōshoku sai-e Fish. Part of the series Dōshoku sai-e

Fish. Part of the series Dōshoku sai-e Folio from the Jakuchū gafu

Folio from the Jakuchū gafu

See also

References

- http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/298027/Ito-Jakuchu

- 「伊藤若冲の初期絵画考<牡丹・百合図>を中心に」『哲学会誌』第29号、学習院大学哲学会、山口真理子 2005年

- Francoeur, Susanne (November 2004). "Goryeo Dynasty: Korea's Age of Enlightenment, 918–1392. By Kim Kumja Paik. San Francisco: Asian Art Museum—Chong—Moon Lee Center for Asian Art and Culture in cooperation with the National Museum of Korea and the Nara National Museum, 2003. 319 pp. $45.00 (paper)". The Journal of Asian Studies. 63 (4): 1154–1156. doi:10.1017/s0021911804002888. ISSN 0021-9118.

- 出光美術館が若冲《鳥獣花木図屏風》など190点をプライスコレクションから購入。2020年に展覧会開催へ, Bijutsu Techo, June 27, 2019

- Marco, Meccarelli. 2015. "Chinese Painters in Nagasaki: Style and Artistic Contaminatio during the Tokugawa Period (1603-1868)" Ming Qing Studies 2015, Pages 175-236.

- https://www.bonhams.com/auctions/20023/lot/455/

- https://www.google.com/culturalinstitute/beta/asset/jakuch%C5%AB-gafu/1gHR3ByP4r5-lQ

- http://www.tokyoartbeat.com/event/2013/0F36

Further reading

- Lippit, Yukio (2012). Colorful Realm: Japanese Bird-and-Flower by Itō Jakuchū. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-48460-0.

- Rosenfield, John M. (1999). Extraordinary Persons: Works by Eccentric, Nonconformist Japanese Artists of the Early Modern Era (1580–1868) in the Collection of Kimiko and John Powers. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard Art Museums.

- Sato, Yasuhiro (2020). The World of Ito Jakuchu: Classical Japanese Painter of All Things Great and Small in Nature. Tokyo: Japan Publishing Industry Foundation for Culture.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Itō Jakuchū. |

- 'Shohaku Show' at the Kyoto National Museum

- Ito Jakuchu's Colorful Realm of Living Beings at the National Gallery of Art, Washington

- An Interview with Joe & Etsuko Price, Collectors of Japanese Art including the world's largest private collection of Jakuchū paintings

- Bridge of dreams: the Mary Griggs Burke collection of Japanese art, a catalog from The Metropolitan Museum of Art Libraries (fully available online as PDF), which contains material on Itō Jakuchū (see index)