J

J, or j, is the tenth letter in the modern English alphabet and the ISO basic Latin alphabet. Its usual name in English is jay (pronounced /ˈdʒeɪ/), with a now-uncommon variant jy /ˈdʒaɪ/.[1][2] When used in the International Phonetic Alphabet for the y sound, it may be called yod or jod (pronounced /ˈjɒd/ or /ˈjoʊd/).[3]

| J | |

|---|---|

| J j ȷ | |

| (See below) | |

| |

| Usage | |

| Writing system | Latin script |

| Type | Alphabetic |

| Language of origin | Latin language |

| Phonetic usage | [j] [dʒ]~[tʃ] [x~h] [ʒ] [ɟ] [ʝ] [dz] [tɕ] [gʱ] [t]~[dʑ] [ʐ] [ʃ] [c̬] [i] /dʒeɪ/ /dʒaɪ/ |

| Unicode codepoint | U+004A, U+006A, U+0237 |

| Alphabetical position | 10 |

| History | |

| Development | |

| Time period | 1524 to present |

| Descendants | • Ɉ • Tittle • J |

| Sisters | І Ј י ي ܝ ی ࠉ 𐎊 ዪ Ⴢ ⴢ ჲ ☞ ☚ |

| Variations | (See below) |

| Other | |

| Other letters commonly used with | j(x), ij |

|

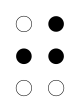

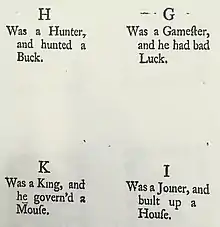

History

The letter J used to be used as the swash letter I, used for the letter I at the end of Roman numerals when following another I, as in XXIIJ or xxiij instead of XXIII or xxiii for the Roman numeral representing 23. A distinctive usage emerged in Middle High German.[4] Gian Giorgio Trissino (1478–1550) was the first to explicitly distinguish I and J as representing separate sounds, in his Ɛpistola del Trissino de le lettere nuωvamente aggiunte ne la lingua italiana ("Trissino's epistle about the letters recently added in the Italian language") of 1524.[5] Originally, 'I' and 'J' were different shapes for the same letter, both equally representing /i/, /iː/, and /j/; however, Romance languages developed new sounds (from former /j/ and /ɡ/) that came to be represented as 'I' and 'J'; therefore, English J, acquired from the French J, has a sound value quite different from /j/ (which represents the initial sound in the English language word "yet").

Pronunciation and use

| Most common pronunciation: /j/ Languages in italics do not use the Latin alphabet | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Language | Dialect(s) | Pronunciation

(IPA) |

Environment | Notes |

| Arabic | Standard; most dialects | /dʒ/ | Latinization | |

| Gulf | /j/ | Latinization | ||

| Sudanese, Omani, Yemeni | /ɟ/ | Latinization | ||

| Levantine, Maghrebi | /ʒ/ | Latinization | ||

| Azeri | /ʒ/ | |||

| Basque[6] | Bizkaian | /dʒ/ | ||

| Lapurdian | /j/ | also used in southwest Bizkaian | ||

| Low Navarrese | /ɟ/ | also used in south Lapurdian | ||

| High Navarrese | /ʃ/ | |||

| Gipuzkoan | /x/ | also used in east Bizkaian | ||

| Zuberoan | /ʒ/ | |||

| Catalan | /ʒ/ | |||

| English | /dʒ/ | |||

| French | /ʒ/ | |||

| Hindi | /dʒ/ | |||

| Hokkien | /dz/~/dʑ/ | |||

| /z/~/ʑ/ | ||||

| Igbo | /dʒ/ | |||

| Indonesian | /dʒ/ | |||

| Japanese | /dʑ/~/ʑ/ | /ʑ/ and /dʑ/ distinct in some dialects, see Yotsugana | ||

| Kiowa | /t/ | |||

| Konkani | /ɟ/ | |||

| Korean | North | /ts/ | ||

| /dz/ | after vowels | |||

| South | /tɕ/ | |||

| /dʑ/ | after vowels | |||

| Kurdish | /ʒ/ | |||

| Luxembourgish | /j/ | |||

| /ʒ/ | Some words | |||

| Malay | /dʒ/ | |||

| Mandarin | Standard | /tɕ/ | Pinyin latinization | |

| /ʐ/ | Wade–Giles latinization | |||

| Manx | /dʒ/ | |||

| Oromo | /dʒ/ | |||

| Pashto | /dz/ | |||

| Portuguese | /ʒ/ | |||

| Romanian | /ʒ/ | |||

| Scots | /dʒ/ | |||

| Shona | /dʒ/ | |||

| Somali | /dʒ/ | |||

| Spanish | Standard | /x/ | ||

| Some dialects | /h/ | |||

| Swahili | /ɟ/ | |||

| Tamil | /dʑ/ | |||

| Tatar | /ʐ/ | |||

| Telugu | /dʒ/ | |||

| Turkish | /ʒ/ | |||

| Turkmen | /dʒ/ | |||

| Yoruba | /ɟ/ | |||

| Zulu | /dʒ/ | |||

English

In English, ⟨j⟩ most commonly represents the affricate /dʒ/. In Old English, the phoneme /dʒ/ was represented orthographically with ⟨cg⟩ and ⟨cȝ⟩.[7] Under the influence of Old French, which had a similar phoneme deriving from Latin /j/, English scribes began to use ⟨i⟩ (later ⟨j⟩) to represent word-initial /dʒ/ in Old English (for example, iest and, later jest), while using ⟨dg⟩ elsewhere (for example, hedge).[7] Later, many other uses of ⟨i⟩ (later ⟨j⟩) were added in loanwords from French and other languages (e.g. adjoin, junta). The first English language book to make a clear distinction between ⟨i⟩ and ⟨j⟩ was published in 1633.[8] In loan words such as raj, ⟨j⟩ may represent /ʒ/. In some of these, including raj, Azerbaijan, Taj Mahal, and Beijing, the regular pronunciation /dʒ/ is actually closer to the native pronunciation, making the use of /ʒ/ an instance of a hyperforeignism.[9] Occasionally, ⟨j⟩ represents the original /j/ sound, as in Hallelujah and fjord (see Yodh for details). In words of Spanish origin, where ⟨j⟩ represents the voiceless velar fricative [x] (such as jalapeño), English speakers usually approximate with the voiceless glottal fricative /h/.

In English, ⟨j⟩ is the fourth least frequently used letter in words, being more frequent only than ⟨z⟩, ⟨q⟩, and ⟨x⟩. It is, however, quite common in proper nouns, especially personal names.

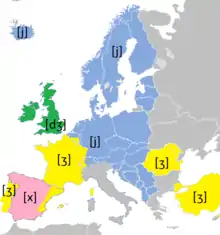

Germanic and Eastern-European languages

The great majority of Germanic languages, such as German, Dutch, Icelandic, Swedish, Danish and Norwegian, use ⟨j⟩ for the palatal approximant /j/, which is usually represented by the letter ⟨y⟩ in English. Notable exceptions are English, Scots and (to a lesser degree) Luxembourgish. ⟨j⟩ also represents /j/ in Albanian, and those Uralic, Slavic and Baltic languages that use the Latin alphabet, such as Hungarian, Finnish, Estonian, Polish, Czech, Serbo-Croatian, Slovak, Latvian and Lithuanian. Some related languages, such as Serbo-Croatian and Macedonian, also adopted ⟨j⟩ into the Cyrillic alphabet for the same purpose. Because of this standard, the lower case letter was chosen to be used in the IPA as the phonetic symbol for the sound.

Romance languages

In the Romance languages, ⟨j⟩ has generally developed from its original palatal approximant value in Latin to some kind of fricative. In French, Portuguese, Catalan, and Romanian it has been fronted to the postalveolar fricative /ʒ/ (like ⟨s⟩ in English measure). In Spanish, by contrast, it has been both devoiced and backed from an earlier /ʝ/ to a present-day /x/ ~ /h/,[10] with the actual phonetic realization depending on the speaker's dialect.

In modern standard Italian spelling, only Latin words, proper nouns (such as Jesi, Letojanni, Juventus etc.) or those borrowed from foreign languages have ⟨j⟩. Until the 19th century, ⟨j⟩ was used instead of ⟨i⟩ in diphthongs, as a replacement for final -ii, and in vowel groups (as in Savoja); this rule was quite strict in official writing. ⟨j⟩ is also used to render /j/ in dialectal spelling, e.g. Romanesco dialect ⟨ajo⟩ [ajo] (garlic; cf. Italian aglio [aʎo]). The Italian novelist Luigi Pirandello used ⟨j⟩ in vowel groups in his works written in Italian; he also wrote in his native Sicilian language, which still uses the letter ⟨j⟩ to represent /j/ (and sometimes also [dʒ] or [gj], depending on its environment).[11] The Maltese language is a Semitic language, not a Romance language; but has been deeply influenced by them (especially Sicilian) and it uses ⟨j⟩ for the sound /j/ (cognate of the Semitic yod).

Basque

In Basque, the diaphoneme represented by ⟨j⟩ has a variety of realizations according to the regional dialect: [j, ʝ, ɟ, ʒ, ʃ, x] (the last one is typical of Gipuzkoa).

Non-European languages

Among non-European languages that have adopted the Latin script, ⟨j⟩ stands for /ʒ/ in Turkish and Azerbaijani, for /ʐ/ in Tatar. ⟨j⟩ stands for /dʒ/ in Indonesian, Somali, Malay, Igbo, Shona, Oromo, Turkmen, and Zulu. It represents a voiced palatal plosive /ɟ/ in Konkani, Yoruba, and Swahili. In Kiowa, ⟨j⟩ stands for a voiceless alveolar plosive, /t/.

⟨j⟩ stands for /dʒ/ in the romanization systems of most of the Languages of India such as Hindi and Telugu and stands for /dʑ/ in the Romanization of Japanese and Korean.

For Chinese languages, ⟨j⟩ stands for /t͡ɕ/ in Mandarin Chinese Pinyin system, the unaspirated equivalent of ⟨q⟩ (/t͡ɕʰ/). In Wade–Giles, ⟨j⟩ stands for Mandarin Chinese /ʐ/. Pe̍h-ōe-jī of Hokkien and Tâi-lô for Taiwanese Hokkien, ⟨j⟩ stands for /z/ and /ʑ/, or /d͡z/ and /d͡ʑ/, depending on accents. In Jyutping for Cantonese, ⟨j⟩ stands for /j/.

The Royal Thai General System of Transcription does not use the letter ⟨j⟩, although it is used in some proper names and non-standard transcriptions to represent either จ [tɕ] or ช [tɕʰ] (the latter following Pali/Sanskrit root equivalents).

In romanized Pashto, ⟨j⟩ represents ځ, pronounced [dz].

In the Qaniujaaqpait spelling of the Inuktitut language, ⟨j⟩ is used to transcribe /j/.

Related characters

- 𐤉 : Semitic letter Yodh, from which the following symbols originally derive

- I i : Latin letter I, from which J derives

- ȷ : Dotless j

- ᶡ : Modifier letter small dotless j with stroke[12]

- ᶨ : Modifier letter small j with crossed-tail[12]

- IPA-specific symbols related to J: ʝ ɟ ʄ ʲ

- Uralic Phonetic Alphabet-specific symbols related to J: U+1D0A ᴊ LATIN LETTER SMALL CAPITAL J,[13] U+1D36 ᴶ MODIFIER LETTER CAPITAL J,[13] and U+2C7C ⱼ LATIN SUBSCRIPT SMALL LETTER J[14]

- J with diacritics: Ĵ ĵ ǰ Ɉ ɉ J̃ j̇̃

Computing codes

| Preview | J | j | ȷ | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unicode name | LATIN CAPITAL LETTER J | LATIN SMALL LETTER J | LATIN SMALL LETTER DOTLESS J | |||

| Encodings | decimal | hex | decimal | hex | decimal | hex |

| Unicode | 74 | U+004A | 106 | U+006A | 567 | U+0237 |

| UTF-8 | 74 | 4A | 106 | 6A | 200 183 | C8 B7 |

| Numeric character reference | J | J | j | j | ȷ | ȷ |

| Named character reference | ȷ | |||||

| EBCDIC family | 209 | D1 | 145 | 91 | ||

| ASCII 1 | 74 | 4A | 106 | 6A | ||

- 1 Also for encodings based on ASCII, including the DOS, Windows, ISO-8859 and Macintosh families of encodings.

Unicode also has a dotless variant, ȷ (U+0237). It is primarily used in Landsmålsalfabet and in mathematics. It is not intended to be used with diacritics since the normal j is softdotted in Unicode (that is, the dot is removed if a diacritic is to be placed above; Unicode further states that, for example i+ ¨ ≠ ı+¨ and the same holds true for j and ȷ).[15]

In Unicode, a duplicate of 'J' for use as a special phonetic character in historical Greek linguistics is encoded in the Greek script block as ϳ (Unicode U+03F3). It is used to denote the palatal glide /j/ in the context of Greek script. It is called "Yot" in the Unicode standard, after the German name of the letter J.[16][17] An uppercase version of this letter was added to the Unicode Standard at U+037F with the release of version 7.0 in June 2014.[18][19]

Wingdings smiley issue

In the Wingdings font by Microsoft, the letter "J" is rendered as a smiley face (this is distinct from the Unicode code point U+263A, which renders as ☺). In Microsoft applications, ":)" is automatically replaced by a smiley rendered in a specific font face when composing rich text documents or HTML email. This autocorrection feature can be switched off or changed to a Unicode smiley.[20] [21]

Other uses

- In international licence plate codes, J stands for Japan.

- In mathematics, j is one of the three imaginary units of quaternions.

- In the Metric system, J is the symbol for the joule, the SI derived unit for energy.

- In some areas of physics, electrical engineering and related fields, j is the symbol for the imaginary unit (the square root of -1) (in other fields the letter i is used, but this would be ambiguous as it is also the symbol for current).

- A J can be a slang term for a joint (marijuana cigarette)

- In the United Kingdom under the old system (before 2001), a licence plate that begins with "J" for example "J123 XYZ" would correspond to a vehicle registered between August 1, 1991 and July 31, 1992. Again under the old system, a licence plate that ends with "J" for example "ABC 123J" would correspond to a vehicle that was registered between August 1, 1970 and July 31, 1971.[22]

Other representations

References

- "J", Oxford English Dictionary, 2nd edition (1989)

- "J" and "jay", Merriam-Webster's Third New International Dictionary of the English Language, Unabridged (1993)

- "yod". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- "Wörterbuchnetz". Retrieved 22 December 2016.

- De le lettere nuωvamente aggiunte ne la lingua Italiana in Italian Wikisource.

- Trask, R. L. (Robert Lawrence), 1944-2004. (1997). The history of Basque. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-13116-2. OCLC 34514667.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Hogg, Richard M.; Norman Francis Blake; Roger Lass; Suzanne Romaine; R. W. Burchfield; John Algeo (1992). The Cambridge History of the English Language. Cambridge University Press. p. 39. ISBN 0-521-26476-6.

- English Grammar, Charles Butler, 1633

- Wells, John (1982). Accents of English 1: An Introduction. Cambridge, UN: Cambridge University Press. p. 108. ISBN 0-521-29719-2.

- Penny, Ralph John (2002). A History of the Spanish Language. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-01184-1.

- Cipolla, Gaetano (2007). The Sounds of Sicilian: A Pronunciation Guide. Mineola, NY: Legas. pp. 11–12. ISBN 9781881901518. Retrieved 2013-03-31.

- Constable, Peter (2004-04-19). "L2/04-132 Proposal to add additional phonetic characters to the UCS" (PDF).

- Everson, Michael; et al. (2002-03-20). "L2/02-141: Uralic Phonetic Alphabet characters for the UCS" (PDF).

- Ruppel, Klaas; Rueter, Jack; Kolehmainen, Erkki I. (2006-04-07). "L2/06-215: Proposal for Encoding 3 Additional Characters of the Uralic Phonetic Alphabet" (PDF).

- The Unicode Standard, Version 8.0, p. 293 (at the very bottom)

- Nick Nicholas, "Yot" Archived 2012-08-05 at Archive.today

- "Unicode Character 'GREEK LETTER YOT' (U+03F3)". Retrieved 22 December 2016.

- "Unicode: Greek and Coptic" (PDF). Retrieved 2014-06-26.

- "Unicode 7.0.0". Unicode Consortium. Retrieved 2014-06-26.

- Pirillo, Chris (26 June 2010). "J Smiley Outlook Email: Problem and Fix!". Retrieved 22 December 2016.

- Chen, Raymond (23 May 2006). "That mysterious J". The Old New Thing. MSDN Blogs. Retrieved 2011-04-01.

- "Car Registration Years | Suffix Number Plates | Platehunter". www.platehunter.com. Retrieved 2018-12-20.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to J. |

The dictionary definition of J at Wiktionary

The dictionary definition of J at Wiktionary The dictionary definition of j at Wiktionary

The dictionary definition of j at Wiktionary- . Encyclopædia Britannica. 15 (11th ed.). 1911.