Jacques Vergès

Jacques Vergès (5 March 1925 – 15 August 2013) was a Siamese-born French lawyer, writer and political activist, known for his defense of FLN militants during the Algerian War of Independence. He was imprisoned for his activism in 1960 and temporarily lost his license to officially practice law. A supporter of the Palestinian fedayeen in the 1960s, he disappeared from 1970 to 1978 without ever explaining his whereabouts during that period. He had been involved then in legal cases for high-profile defendants charged with terrorism or war crimes, including Nazi Klaus Barbie in 1987,[1] terrorist Carlos the Jackal in 1994, and former Khmer Rouge head of state Khieu Samphan in 2008. He also infamously defended Holocaust denier Roger Garaudy in 1998.

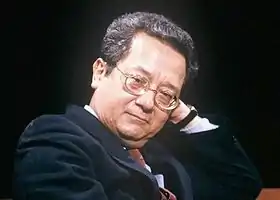

Jacques Vergès | |

|---|---|

During the trial of Khieu Samphan in 2011 | |

| Born | 5 March 1925 |

| Died | 15 August 2013 (aged 88) Paris, France |

| Nationality | French and Algerian |

| Education | University of Paris law degree |

| Occupation | Lawyer |

| Known for | Lawyer who represented well-known war criminals[1] |

| Spouse(s) | Djamila Bouhired |

| Children | Jacques-Loys Vergès (1951), Meriem Vergès (1967), Liess Vergès (1969) |

| Parent(s) | Raymond Vergès, Pham Thi Khang |

Vergès attracted widespread public attention in the 1950s for his use of trials as a forum for expressing views against French rule in Algeria, questioning the authority of the prosecution and causing chaos in proceedings – a method he promoted as "rupture defense" in his book De la stratégie judiciaire. An outspoken anti-imperialist, he continued his vocal political activism in the 2000s, including opposing the War on Terror.[note 1] The media sensationalized his activities with the sobriquet "the Devil's advocate",[note 2] and Vergès himself contributed to his "notorious" public persona by such acts as titling his autobiography The Brilliant Bastard[note 3] and giving provocative replies in interviews, such as "I'd even defend Bush! But only if he agrees to plead guilty."[2][3]

Biography

Born on 5 March 1925 in Ubon Ratchathani, Siam, and brought up on the island of Réunion,[4][5] Jacques Vergès was the son of Raymond Vergès, a French diplomat, and a Vietnamese teacher named Pham Thi Khang. In 1942, with his father's encouragement, he sailed to Liverpool to become part of the Free French Forces under Charles de Gaulle, and to participate in the anti-Nazi resistance.[6] In 1945 he joined the French Communist Party. After the war he went to the University of Paris to study law (while his twin brother Paul Vergès went on to become the leader of the Reunionese Communist Party and a member of the European Parliament).[7] In 1949 Jacques became president of the AEC (Association for Colonial Students), where he met and befriended Pol Pot.[8] In 1950, at the request of his Communist mentors, he went to Prague to lead a youth organization for four years.[9]

Jacques Vergès was elected Secrétaire de la Conférence du barreau de Paris

Algerian independence movement

After returning to France, Vergès became a lawyer and quickly gained fame for his willingness to take controversial cases. During the struggle in Algiers he defended many accused of terrorism by the French government. He was a supporter of the Algerian armed independence struggle against France, comparing it to French armed resistance to the Nazi German occupation in the 1940s. Vergès became a nationally known figure following his defence of the anti-French Algerian guerrilla Djamila Bouhired on terrorism charges: she was convicted of blowing up a café and killing eleven people inside it.[8] This is where he pioneered the rupture strategy, in which he accused the prosecution of the same offenses as the defendants.[10] She was sentenced to death but pardoned and freed following public pressure brought on by Vergès' efforts. After some years she married Vergès, who had by then converted to Islam. They had two children, Meriem and Liess Vergès, later followed by a granddaughter, Fatima Vergès-Habboub, daughter of Meriem and her husband Fouad.[11] In an effort to limit Vergès' success at defending Algerian clients, he was sentenced to two months in jail in 1960 and temporarily lost his licence to officially practice law for anti-state activities.[12] After Algeria gained its independence in 1962, Vergès obtained Algerian citizenship, going by the name of Mansour.[13]

Israel and the Palestinians

In 1965, Vergès arrived in Israel, seeking to represent Mahmud Hijazi (מחמוד חיג'אזי), a Palestinian member of the Fatah movement who had at the time been sentenced to death by an Israeli military court on charges of terrorism, for crossing into Israel and setting a small demolition charge near the National Water Conduit in the Galilee.[14] Israel's Justice Minister Dov Yosef forbade Hijazi's being represented by a foreign lawyer. Nevertheless, though Vergès did not succeed in getting to represent Hijazi in court, his initiative generated considerable publicity and controversy which were influential in Hijazi's death sentence being eventually commuted by an appeals court. (Hijazi was later released in a 1971 prisoner exchange). The Hijazi affair had a long-lasting effect: Israeli civil and military courts, since then and up to the present, refrain from imposing the death penalty on Palestinians charged with terrorism, even in the most severe cases where an accused was found guilty of multiple murder charges.

Missing years

From 1970 to 1978, Vergès disappeared from public view without explanation. He refused to comment about those years, remarking in an interview with Der Spiegel that "It's highly amusing that no one, in our modern police state, can figure out where I was for almost ten years."[15] Vergès was last seen on 24 February 1970. He left his wife, Djamila, and cut off all his ties, leaving friends and family to wonder if he had been killed.[16] His whereabouts during these years have remained a mystery. Many of his close associates of the time assume that he was in Cambodia with the Khmer Rouge, a rumour Pol Pot (Brother #1) and Ieng Sary (Brother #3)[17] both denied. There have also been claims that Vergès was spotted in Paris as well as in Arab countries in the company of Palestinian militant groups.[18]

Defence

After Vergès's return to normal life he resumed his legal practice, defending Georges Ibrahim Abdallah, convicted of terrorism, and Nazi war criminal Klaus Barbie.

The thrust of his defence in the latter case was that Barbie was being singled out for prosecution while the French state conveniently ignored other cases that qualified as crimes against humanity.[1] Vergès adopted a tu quoque defense, asking the judges "is a crime against humanity is to be defined as only one of Nazis against the Jews or if it applies to more seriously crimes...the crimes of imperialists against people struggling for their independence?", going on to say there was nothing his client did against the Resistance that was not done by "certain French officers in Algeria" whom Vergès noted could not be prosecuted because of de Gaulle's amnesty of 1962.[19] As such, Vergès argued that the republic had no right to convict Barbie of anything given that French officers like the war hero General Jacques Massu had also engaged in torture and extrajudicial executions during the fight against the FLN.[19] Vergès argued in impassioned speeches before the court that the main conflict motivating history was the struggle between the "Global North" vs. the "Global South", and that American policy in the Vietnam war and French policy during the Algerian war were the "true face" of the West.[20] Vergès maintained to convict Barbie was a base act of hypocrisy for a French court as his actions were those of a typical Westerner, and therefore he could not be punished for doing merely other Westerners had done.[20]

Besides for his tu quoque defense of arguing that French actions in the Algerian War were no different from Barbie's, Vergès spent much time attempting to prove the Resistance hero Jean Moulin had been betrayed by either the Communists, the Gaullists, or both, which led him to argue Barbie was less culpable than those who had betrayed Moulin.[21] Vergès claimed Moulin's colleagues were "playing a double game" and all those in the Resistance "whether they were anti-Gaullists or anti-Communists forgot their duty to the Resistance because of partisan political passions".[22] At one point, Vergès claimed that Moulin had actually wanted to be tortured to death and tipped off Barbie himself.[23] Under French law, defense lawyers are entitled to use competing theories in defense of their clients, unlike the prosecution who must stick to only one line of argument. Barbie was not on trial for the torture and murder of Moulin as the statute of limitations in the Moulin case had expired, but instead on trial for crimes against humanity for his role in deporting Jews from Lyons in 1942-44, for which there was no statute of limitations.[23] Barbie was on trial for his role in the arrest and deportation of 44 Jewish children from the Izieu orphanage on 6 April 1944.[24] Of the 44 children, 42 were killed at Auschwitz.[24]

Vergès seems to have brought in the Moulin case as part of his defense of Barbie as a strategy of historical obfuscation and confusion, as he argued that the truth about who betrayed Moulin to Barbie can never truly be answered.[23] The implication of Vergès's argument was that other aspects of Barbie's life were likewise uncertain and unknowable, making the question of whatever Barbie committed crimes against humanity impossible to answer. Despite Vergès's best efforts at obfuscation and a tu quoque defense of comparing Barbie's actions to French actions in Algeria and American actions in Vietnam, the court found Barbie guilty of crimes against humanity, sentencing him to life imprisonment.[23] Reviewing the film Hôtel Terminus: The Life and Times of Klaus Barbie, the film critic David Denby wrote the climax of the film was when the French filmmaker Marcel Ophüls pressed the "despicable" Vergès during an interview about his defense of Barbie, whom Denby wrote "...persists in pretending that Barbie is a victim of some sort".[25] Vergès was paid to defend Barbie by the Swiss Nazi financier François Genoud.

In 1999 Vergès sued Amnesty International on behalf of the government of Togo.[26] In 2001, on behalf of Idriss Déby, president of Chad, Omar Bongo, president of Gabon, and Denis Sassou-Nguesso, President of the Republic of the Congo, he sued François-Xavier Verschave for his book Noir silence denouncing the crimes of the Françafrique on the charges of "offense toward a foreign state leader", using an arcane 1881 law.[27] The attorney general observed how this crime recalled the lese majesty crime; the court thus deemed it contrary to the European Convention on Human Rights, thus leading to Verschave's acquittal.[27]

After the US-led coalition forces invaded Iraq in March 2003 and deposed Saddam Hussein, many former leaders in the Baathist regime were arrested. In May 2008, Tariq Aziz assembled a team that included Vergès as well as a French-Lebanese and four Italian lawyers.[28] In late 2003, Vergès also offered to defend Hussein if he was asked to. However, the Hussein family opted not to use Vergès.[29]

In April 2008, former Khmer Rouge head of state Khieu Samphan made his first appearance at Cambodia's genocide tribunal. Vergès represented him, using the defence that, while Samphan has never denied that many people in Cambodia were killed, as head of state he was never directly responsible.[30]

According to The Economist, "history was his first love, and he still sometimes dreamed of deciphering Etruscan or Linear A, unfolding the secrets of mysterious civilisations."[31]

Jacques Vergès died on 15 August 2013 of a heart attack in Paris at the age of 88.[4][32] His funeral was attended by Roland Dumas and Dieudonné M'bala M'bala. Vergès is buried in the Montparnasse Cemetery.[33]

In popular culture

- In 1987 Vergès appeared on a memorable episode of the live British discussion television programme After Dark along with Eli Rosenbaum, Neal Ascherson, Philippe Daudy and Paul Oestreicher.

- Vergès was portrayed by Nicolas Briançon in the 2010 French film Carlos.

See also

- List of solved missing person cases

- L'Avocat de la terreur (Terror's Advocate), a 2007 documentary about Vergès, directed and narrated by Barbet Schroeder.

Notes

- In La démocratie à visage obscène. Le vrai catéchisme de George W. Bush, 2004, ISBN 2710327317.

- The sobriquet The Devil's advocate was used by the European press to describe not only Jacques Vergès but also Giovanni Di Stefano.

- The French epithet has sometimes been translated as "luminous bastard".

References

- "1987: Nazi war criminal Klaus Barbie gets life". BBC News. 3 July 1987. Retrieved 12 April 2008.

- Event occurs at 01:58:42 – Director:Barbet Schroeder, Interviewee:Jacques Vergès (12 April 2008). Avocat de la terreur, L' (Documentary) (DVD). Canal+ [fr]. Retrieved 12 April 2008.I can't stand a man being humiliated, even an enemy. For a lone man to be insulted by a lynch mob. I was asked: "Would you defend Hitler?" "I said I'd even defend Bush! "But only if he agrees to plead guilty."

- Turan, Kenneth (12 October 2007). "Giving monsters a strong defense". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 13 August 2008.

- McFadden, Robert D. (16 August 2013). "Jacques Vergès, Defender of Terrorists And War Criminals, Is Dead at 88". The New York Times.

- "Jacques Vergès: 'The Devil's advocate'". BBC News. 29 March 2004. Retrieved 12 April 2008.

- Event occurs at 00:04:04 – Director:Barbet Schroeder, Interviewee:Jacques Vergès (12 April 2008). Avocat de la terreur, L' (Documentary) (DVD). Canal+ [fr]. IMDB – 1032854. Retrieved 12 April 2008.

For France to disappear was intolerable to me. That's why I enlisted.

- "MEP profile". European Union. 2007. Retrieved 13 April 2008.

- Merkin, Daphne (21 October 2007). "Speak No 'Evil'". New York Times. Retrieved 12 April 2008.

- van Hoeij, Boyd (2008). "review: L'avocat de la terreur (Terror's Advocate) (Rotterdam 2008)". european-films.net. Archived from the original on 3 April 2008. Retrieved 13 April 2008.

Not mentioned either are his controversial defence of Holocaust denier Roger Garaudy and his formative work in Prague in the 1950s – in the middle of the Cold War, though possible connections with secret services and many underground organisations in countries ranging from Germany to Israel and Algeria are hinted at and explored.

- MARCO CHOWN OVED (2 November 2008). "The Jackal's defender has his own one-man show". Radio France Internationale. Retrieved 9 November 2008.

- Ma'n Abul Husn (2007). "Women of Distinction: Djamila Bouhired The Symbol of National Liberation". pub. Retrieved 12 April 2008.

- Michael Radu (14 April 2004). "Saddam Circus Is Coming to Town: the Strange Story of Jacques Vergès". Foreign Policy Research Institute. Archived from the original on 13 August 2008. Retrieved 14 August 2008.

At a time when France was at war, Vergès openly supported and defended terrorists and their French accomplices— that is, traitors. He was jailed for this for two months in 1960 and temporarily disbarred.

- Airdj, Jamila (16 August 2013). "Jacques Vergès, l'homme aux mille vies". Le Point (in French). Retrieved 16 August 2013.

- Yaffe, Aharon (15 April 2008). "Dr". International Institute on Counter-Terrorism. Interdisciplinary Centre Herzliya. Archived from the original on 5 August 2020. Retrieved 5 August 2020.

The Palestinian Liberation Organization, commonly known as the PLO, was founded on January 1st 1965, marking its first operation. On that day, the terrorist Mahmud Hijazi was caught having placed a small demolition charge at the National Water Carrier conduit in the Galilee.

- "Interview with Notorious Lawyer Jacques Vergès: 'I Shift Events to Outside the Courtroom'". Spiegel.de. 21 November 2008. Retrieved 30 September 2016.

- Event occurs at 00:50:29 – Director:Barbet Schroeder (12 April 2008). Avocat de la terreur, L' (Documentary) (DVD). Canal+ [fr]. IMDB – 1032854. Retrieved 12 April 2008."He was last seen on 24 February 1970, at an anti-colonial rally in Paris. He made a speech and vanished. After three months, Djamila Bouhired and his friends, were sure he was dead."

- Event occurs at 00:52:56 – Director:Barbet Schroeder, Interviewee: Ieng Sary (12 April 2008). Avocat de la terreur, L' (Documentary) (DVD). Canal+ [fr]. IMDB – 1032854. Retrieved 12 April 2008.

The Brilliant Bastard In that book are two passages I remember. It says ... that Jacques Vergès could have been in Cambodia. I remember that Pol Pot wrote in the margin: No.

- Event occurs at 00:55:44 – Director: Barbet Schroeder, Interviewee: Pascal (12 April 2008). Avocat de la terreur, L' (Documentary) (DVD). Canal+ [fr]. IMDB – 1032854. Retrieved 12 April 2008.

It was in May 1973, ... several politicians ... were meeting at Arafat's HQ. ... Arafat suddenly looked at [Abou Hassan Salameh PLO security chief] and asked: "Who is this Vergès? What is he?" Abou Hassan Salameh answered literally: "He's an important lawyer who defends the Palestinian cause." Arafat smiled and said: "Keep working with him." My codename was "Pascal". And Vergès? "Mansour".

- Cohen, William "The Algerian War, the French State and Official Memory" pp. 219–239 from Réflexions Historiques, Vol. 28, No. 2, Summer 2002, p. 230.

- Finkielkraut, Alain Remembering in Vain: The Klaus Barbie Trial and Crimes Against Humanity, New York Columbia University Press, 2010 p.52

- Clinton, Alan Jean Moulin, 1899–1943 The French Resistance and the Republic, London: Macmillan 2002 pages 203–204.

- Clinton, Alan Jean Moulin, 1899–1943 The French Resistance and the Republic, London: Macmillan 2002 page 203.

- Clinton, Alan Jean Moulin, 1899–1943 The French Resistance and the Republic, London: Macmillan, 2002. p. 204.

- Finkielkraut, Alain Remembering in Vain: The Klaus Barbie Trial and Crimes Against Humanity, New York Columbia University Press, 2010 p.89

- Denby, David "Criminal Element" pp. 75–76 from New York Magazine", 17 October 1988 p. 76.

- "Togo to sue Amnesty International". BBC Newsb. 20 May 1999. Retrieved 12 April 2008.

- "French author wins Africa book case". BBC News. 25 April 2001. Retrieved 12 April 2008.

- "Tariq Aziz trial resumes in Iraq". BBC News. 20 May 2008. Retrieved 20 May 2008.

- "Saddam family slims defence team". BBC News. 8 August 2005. Retrieved 14 August 2008.

- "Khmer Rouge leader seeks release". BBC News. 23 April 2008. Retrieved 23 April 2008.

- "Jacques Vergès". 28 August 2013 – via The Economist.

- "Controversial French lawyer Verges dies at 88 - FRANCE 24". 21 September 2013. Archived from the original on 21 September 2013.

- "VIDEO. Obsèques religieuses pour "l'avocat du diable", Jacques Vergès" (in French). Leparisien.fr. 20 August 2013. Retrieved 30 September 2016.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Jacques Vergès. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Jacques Vergès |

- Jacques Vergès at IMDb

- Cambodia Tribunal Monitor

- Against the Law by Stéphanie Giry, 14 August 2009

- Meeting the Devil's Advocate: An Interview with Jacques Vergès by Chris Tenove, 26 August 2013.