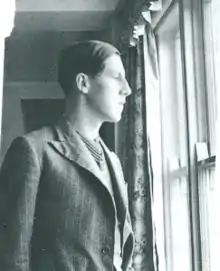

James Alexander Wedderburn St. Clair-Erskine

James Alexander Wedderburn "Hamish" St. Clair-Erskine (23 August 1909 – 17 December 1973) was an English aristocrat aesthete. He was engaged to Nancy Mitford.

James Alexander Wedderburn St. Clair-Erskine | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 23 August 1909 |

| Died | 17 December 1973 (aged 64) |

| Other names | Hamish St. Clair-Erskine |

| Education | Eton College |

| Alma mater | Oxford University |

| Parent(s) | The 5th Earl of Rosslyn |

| Awards | Military Cross |

Early life

James Alexander Wedderburn nicknamed "Hamish" was the son of James St Clair-Erskine, 5th Earl of Rosslyn (1869–1939). His siblings were Mary St Clair-Erskine Dunn Campbell McCabe Dunn (1912–1993), Rosabelle St Clair-Erskine (1891–1956) and Francis St Clair-Erskine, Lord Loughborough (1892–1929).[1]

At Eton College, St Clair-Erskine was the lover of Tom Mitford.[2] He attended Oxford University, where he was friends with English poet Sir John Betjeman. In the Letters edited by Betjeman's daughter, Candida Lycett Green, and published in 1996, she remembers how her father and St. Clair-Erskine "went out in fast cars, driving all night in the flat country near Coolham".[3] According to James Lees-Milne's diaries: "At Oxford he had the most enchanting looks – mischievous, twinkling eyes, slanting eyebrows. He was slight of build, well dressed, gay as gay, always snobbish however, and terribly conscious of his nobility [...] the toast of the university."[4] At Oxford he was friends with Evelyn Waugh.[5]

Career

He fought in the World War II, became a Major in the Coldstream Guards, escaping from a prison camp and walking through Italy to join the Allied troops. He was awarded a Military Cross in 1943.[4][6]

In 1969, together with Anthony Rhodes, he translated Tapestries by Mercedes Viale Ferrero.[7]

He was the dame de compagnie to Daisy Fellowes and Enid Kenmare.[4]

Personal life

Hamish St. Clair-Erskine was gay, but nevertheless, Nancy Mitford fell in love with him, and it was due to this unrequited love that she attempted suicide and wrote her first novel, Highland Fling: the male lead is based upon St. Clair-Erskine.[8]

In the 1920s he was friends with Aileen Sibell Mary Guinness and the Hon. Brinsley Sheridan Bushe Plunket and was guest to their residence, the Luttrellstown Castle, County Dublin.[9]

He was good friends with Patrick Leigh Fermor and his wife Joan: in the 1940s the three of them drove down through France and Italy, and later, Joan accompanied Peter Quennell and St. Clair-Erskine to Sicily, where she was to take the photographs of an article Quennell was writing.[10]

At St. Clair-Erskine's death in 1973, Alan Payan Pryce-Jones described him as a "bright apparition who once upon a time swept past them like a kingfisher: all colour and sparkle and courage [...] [he found] small place in a world which turned away from an unambitious charmer whose only enduring gift was his charm".[11]

Legacy

Painter Adrian Maurice Daintrey took his portrait sold by Christie's on 25 August 2005.[12]

References

- "Hamish St Clair-Erskine". Retrieved 28 September 2017.

- Cooper, Michelle. "Meet The Mitfords". Missing or empty

|url=(help) - "Cars in books". MotorSport. 1996. Retrieved 28 September 2017.

- Lees-Milne, James; Bloch, Michael (2011). Diaries, 1971–1983. Hachette UK. p. 299. ISBN 9781848547100. Retrieved 28 September 2017.

- "Day Four (of a four-day racket.)". Retrieved 28 September 2017.

- "Recommendation for Award for St Clair-Erskine, James Alexander Wedderburn Rank: ..." Retrieved 28 September 2017.

- "Tapestries". Retrieved 28 September 2017.

- Thompson, Laura (2017). "High Society". Harper's Bazaar. Retrieved 28 September 2017.

- "Temps Perdu Feb 23". Retrieved 28 September 2017.

- Dashing for the Post: The Letters of Patrick Leigh Fermor. Hachette UK. 2016. p. 69. ISBN 9781473622487. Retrieved 28 September 2017.

- Acton, Harold (1994). "The fine art of doing nothing: To be an aesthete is no longer practical, says Hugo Vickers. Harold Acton was one of the last". Independent. Retrieved 28 September 2017.

- "Portrait of Hamish St. Clair Erskine". Retrieved 28 September 2017.