James Scudamore (courtier)

Sir James Scudamore (also spelled Skidmore, Skidmur, Skidmuer or Scidmore)(1568–1619) was a gentleman usher at the court of Queen Elizabeth I. Born at Holme Lacy, Herefordshire, he was the eldest son of John Scudamore, Custos Rotulorum of Herefordshire and his first wife Eleanor Croft, daughter of former Lord Deputy of Ireland James Croft. He would assume that title in 1616, and remained Custos Rotulorum for two years until his own death in 1619. Scudamore was respected for his tilting skill and his embodiment of the ideals of chivalry.

Sir James Scudamore | |

|---|---|

Sir James Scudamore | |

| Born | 1568 Holme Lacy, Herefordshire, England |

| Died | 1619 London, England |

| Resting place | Holme Lacy, Herefordshire, England |

| Nationality | English |

| Occupation | Courtier |

| Title | Sir |

| Predecessor | John Scudamore |

| Successor | John Scudamore, 1st Viscount Scudamore |

| Spouse(s) | Mary Houghton[1] Mary Throckmorton[1] |

| Children | John Scudamore, 1st Viscount Scudamore Sir James Scudamore Barnabas Scudamore |

| Parents |

|

Life as a courtier

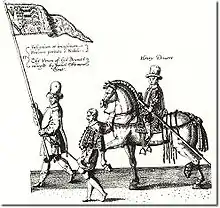

Scudamore became something of a legend in his time at Elizabeth's court. As a young man he idolised Philip Sidney, who, as a poet, soldier, and courtier, exemplified the ideal high-born gentleman of the time. Scudamore sought to emulate Sidney, and befriended him as a teenager, becoming his protege. After Sidney died at the Battle of Zutphen, James Scudamore carried his pennant of arms at his funeral in 1586, aged only eighteen years at the time. He can be seen carrying the pennant near the front of the procession in the funereal roll drawn by Thomas Lant.[2]

Seeing himself as Sidney's successor, the young Scudamore sought to carry on the chivalric tradition with great zeal. He made a name for himself jousting in the tournament; he was one of the primary knights who took part in the Accession Day tilt of 1595. At this tournament, his shield was decorated with the motto "L'escu D'amour", the original Anglo-Norman form of his surname which translated to "shield of love."[3][4] The shield was shaped like a heart, and bore the image of a turtle.[5] Scudamore cut a dashing figure at the tilt-yard – his appearance was thus recounted by the scholar William Higford:

A knightte on horseback is the goodliest sight the worlde can presente to viewe; and is not lesse than a Prince...mee thinkes I see sir James Scudamore...enter the Tilte yarde in a handsome equippage all in compleate Armor, embelished with plumes, his beaver close, mounted vppon a verie highe boundinge horse. I haue seene the shoes of his horse glister aboue the heades of all the people. And when hee came to the encounter or shocke, brake as manie spearse as the beste, Her majestie Queene Elizabeth with a trayne of ladies like the starres in the firmamente, and the whole Courte lookinge vppon him with a verie gratious aspecte. And when hee came to reside with sir John Scudamore his father (two braver gentlemen shall I neuer see togeather att one time, much more a sonne and a father)...Holme Lacie att that time seemed not onlie an Academia, but euen the verie Courte of a Prince.[6]

George Peele, dramatist, wrote:

L’escu d’amour, the arms of loyalty/Lodg’d Skydmore in his heart; and on he came, And well and worthily demeaned himself/In that day’s service: short and plain to be, No Lord nor knight more foreard than was he.

Though by no means a particularly influential nobleman of the Elizabethan court, he was nonetheless greatly admired for his sporting skill. It is apparent from the dimensions of his suits of armour that he was powerfully-built and tall for his time, and he is recorded as having won first place in the Accession Day tilt at least once. The Queen's personal attendance of Scudamore's own tilt-yard at Holme Lacy is a testament to his gallant reputation.

He was a noted soldier, and served, among other places, at the Capture of Cadiz, where he was knighted by the Earl of Essex.

He is said to be the inspiration for the character of "Scudamour," a primary character in Book Four of The Faerie Queene by Edmund Spenser.[7] In the poem, Scudamour is a gallant knight who has had his lover Amoret stolen away from him. He spends the rest of the book unsuccessfully trying to find her; at one point he stops to rest and is tortured in his sleep by a blacksmith wielding a pair of tongs. It is unknown whether this characterisation is intended as a mockery of the actual Scudamore, a light-hearted joke, or an honest representation of his chivalry.

Scudamore officially retired from tilting in 1600. However, he and his father continued to train horses at Holme Lacy.

Political activities

Sir James Scudamore became the deputy lieutenant of Herefordshire on 25 August 1600. He was also made High Sheriff of Herefordshire in 1601, and a member of Parliament for the Herefordshire in 1601 and for several years thereafter. He was appointed to the council of the Welsh Marches on 12 November 1617, and subscribed £30 to the Virginia Company.

Scudamore was originally a Catholic, but he later renounced this religion, along with his father, soon after the turn of the century. After his conversion he became a fervent anti-Catholic and made efforts to curtail the practice of Catholicism. On 19 June 1605, he and three other county officials made a thirty-mile sweep along the border between Herefordshire and Monmouthshire to flush out Catholics. Accompanied by an armed band of men, they made a house by house and village by village search that lasted all night and into the next day. They found "altars, images, books of superstition, relics of idolatry" but no Catholics since they had fled west and south into Wales.

Personal life

In March 1597, Scudamore was married to Mary Houghton, the daughter and co-heiress of Peter Houghton, a London alderman.[1] She died in August 1598, and in the summer of 1598 he remarried to the widow of Sir Thomas Baskerville, coincidentally also named Mary.[1][8] Mary (she is listed as Anne in some sources) was the only daughter of Sir Thomas Throckmorton of Coss Court, by his second wife.[1][9] By her first husband, Mary had one son, Hannibal (5 April 1597 – 1668). Research suggests that his marriage with Lady Mary Scudamore was turbulent. For reasons that are uncertain, she was disliked by the Scudamore family, and Sir James's relatives pressured them to end the marriage. They separated in 1604. Scudamore tried to claim wardship of Hannibal Baskerville and Mary's dower, but by 1621, the case had finally been settled in Hannibal's favour.

Scudamore and his second wife had three sons, John (1601–1671), James (1606–1631), and Barnabas (1609–1652).[1] His eldest son John succeeded his father's political offices and became 1st Viscount Scudamore. James fought in campaigns in the Low Countries, and Barnabas served at the Battle of Newburn under Colonel Charles Vavasour.[10]

A cultured man and patron of literature, Scudamore was a great friend of scholar Thomas Bodley, and contributed to the founding of the Bodleian Library at Oxford.[11]

Scudamore was close with his father John; the two lived together at Holme Lacy for the entirety of Sir James's life, where they trained horses together and hosted such cultural figures as Bodley, scientist John Dee, the polymath Samuel Hartlib and the mathematician Thomas Allen.[12] He was therefore privy to many significant scientific developments of the time. In one memorable incident, Thomas Allen was visiting the Scudamores at Holme Lacy, and was demonstrating his pocket watch to his hosts – at that time, an extremely uncommon and novel device. Frightened by the loud ticking sound of the watch, a maid seized the timepiece and tossed it into a nearby stream.[12] Though Herefordshire was regarded as somewhat of a rustic – even backwards – region, the Scudamore family's patronage of learned and illustrious cultural luminaries of the day ensured for them a high degree of social prestige and a prominent place at the court of the Queen.

Scudamore's stepmother – his father's second wife, Mary Shelton – was a lady of the Privy Chamber of Queen Elizabeth. When she married John Scudamore without permission, the Queen flew into a rage and assaulted her, breaking her finger.

The exact cause of Sir James Scudamore's death is not known; biographer Ian Atherton suggests that it may have stemmed from complications arising from an injured ("gammy") leg which he had been treated for in the past. His father outlived him by four years. In his will, Sir James bequeathed "My armor that I used to Weare" to his son John.

Armour of Sir James Scudamore

Sir James Scudamore left behind some of the finest surviving suits of armour from Elizabethan England, built at the royal Greenwich armoury. His tournament armour features a distinctive armet of the Greenwich style with a high visor and a raised crest; articulated tassets and cuisses, and cris-crossing strips of blued steel inlaid with elaborate gold designs. Another armour, in the later cuirassier style, features a burgonet with a falling-buffe visor and detailed gilding and etching. It is in this armour that he is shown in his portrait which now hangs at Holme Lacy. It is obvious from the painting that the armour was originally coloured a dark shade, and had been polished down to bare steel during its restoration. The pattern for this armour is identical to several others in the Jacob Album including William Compton, 1st Earl of Northampton. A portrait of Compton shows him wearing an armour of more or less identical appearance.

Scudamore's suits of armour were discovered in 1911 packed away in a chest in the attic of an abandoned tower at Holme Lacy, in an extreme state of disrepair and significantly damaged by rust. They had been sitting in a chest beneath an eave through which water had been trickling down into a pool on the floor; they had likely been in this sorry condition for several hundred years. The owner of the estate at the time, Lord Chesterfield, put the armour up at auction for the sum of twenty pounds. A dealer who happened to notice it at the auction informed Chesterfield that it was worth far more, and purchased it for the sum of two thousand pounds. Later, Chesterfield happened by chance upon that dealer's shop, and saw the same armour for sale – for fifteen thousand pounds. Chesterfield sued the dealer and the armour was returned to him.[13] The suits of armour were subsequently purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan and given to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City, where they underwent extensive restoration and had those pieces that were missing altogether replaced with replicas made by Daniel Tachaux. They remain on display today.[13]

| Political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Sir John Scudamore |

Custos Rotulorum of Herefordshire 1616–1619 |

Succeeded by Sir John Scudamore |

References

- Atherton, Ian. Ambition and Failure in Stuart England: The Career of John, First Viscount Scudamore, Manchester University Press, 1999. pg 26–35.

- Atherton, Ian. Ambition and Failure in Stuart England: The Career of John, First Viscount Scudamore, Manchester University Press, 1999. p.34

- https://web.archive.org/web/20091026221310/http://geocities.com/judys-space/Vol1/skidmore.htm

- http://www.channel4.com/history/microsites/R/regencyhouse/programme/kentchurch.html

- Young, Alan, Tudor and Jacobean Tournaments; George Philip 1987, p. 43

- Atherton, Ian. Ambition and Failure in Stuart England: The Career of John, First Viscount Scudamore, Manchester University Press, 1999. p.35

- http://www.britainexpress.com/counties/hereford/churches/Holme-Lacy.htm

- http://www.npg.org.uk/collections/search/person.php?LinkID=mp04019

- Crofts Peerage Archived 11 April 2012 at the Wayback Machine. Viscount Scudamore (I, 1628 – 1716)

- Atherton, Ian. Ambition and Failure in Stuart England: The Career of John, First Viscount Scudamore, Manchester University Press, 1999. p.35

- http://www.british-towns.net/sh/statelyhomes_album.asp?GetPic=13

- Atherton, Ian. Ambition and Failure in Stuart England: The Career of John, First Viscount Scudamore, Manchester University Press, 1999. p. 31

- https://query.nytimes.com/gst/abstract.html?res=9806E2D7103CE633A25751C1A9609C946296D6CF