James Young Simpson

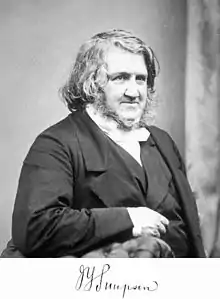

Sir James Young Simpson, 1st Baronet, FRCPE (7 June 1811 – 6 May 1870) was a Scottish obstetrician and a significant figure in the history of medicine. He was the first physician to demonstrate the anaesthetic properties of chloroform on humans and helped to popularise its use in medicine.[1]

James Young Simpson | |

|---|---|

James Simpson | |

| Born | 7 June 1811 Bathgate, West Lothian, Scotland |

| Died | 6 May 1870 (aged 58) Edinburgh, Scotland |

| Alma mater | University of Edinburgh |

| Known for | Use of chloroform as anaesthetic in childbirth, design of obstetric forceps |

| Spouse(s) | Lady Janet Grindlay Simpson (m.1839) |

| Notes | |

James Young Simpson (great nephew) | |

Simpson's intellectual interests ranged from archaeology to an almost taboo subject at the time: hermaphroditism. He was an early advocate of the use of midwives in the hospital environment. Many prominent women also consulted him for their gynaecological problems. Simpson wrote Homœopathy, its Tenets and Tendencies refuting the ideas put forward by Hahnemann.[2]

Simpson was a close friend of Sir David Brewster, and was present at his deathbed. His contribution to the understanding of the anaesthetic properties of chloroform had a major impact on surgery.

Education and early career

James Simpson was born in Bathgate a younger son of Mary Jervais and David Simpson, a baker. He attended the local school, and in 1825, at the age of 14, entered the University of Edinburgh to study for an arts degree.[3] Two years later he began his medical studies at the University,[3] graduating with an MBChB. He became a licentiate of the Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh in 1830[3] and received his MD in 1832.[4] While at University he took additional classes including those delivered by the surgeon Robert Liston. As a result of the quality of his MD thesis on inflammation, Professor of Pathology John Thomson took him on as his assistant.[5]

As a student he became a member and then Senior President of the Royal Medical Society, initiating a lifelong interest in the Society's advancement.[6]

His first role was as a general practitioner in the Stockbridge district based at 2 Deanhaugh Street.[7]

At the age of 28, he succeeded James Hamilton as Professor of Medicine and Midwifery at the University of Edinburgh.[8]

He kept a town house at 52 Queen Street, Edinburgh and a country house near Bathgate.

In religion Simpson was a devout adherent of the Free Church of Scotland, but he refused to sign the Westminster Confession of Faith, because of what he believed to be its literal interpretation of the book of Genesis.[5]

He improved the design of obstetric forceps that to this day are known in obstetric circles as "Simpson's Forceps". His most significant contribution was the introduction of anaesthesia to childbirth.

In 1838, he designed the Air Tractor, the earliest known vacuum extractor to assist childbirth but the method did not become popular until the invention of the ventouse over a century later.[9]

Obstetric anaesthesia

Sir Humphry Davy used the first anaesthetic in 1799: nitrous oxide (laughing gas). William T. G. Morton's demonstration of ether as an anaesthetic in 1846 was initially dismissed because it irritated the lungs of the patients. Chloroform had been invented in 1831, but its uses had not been greatly investigated. Dr Robert Mortimer Glover had first described the anaesthetic properties of chloroform upon animals in 1842 in a thesis which won the Harveian Society's Gold Medal that year, but had not thought to use it on humans (fearing its safety).[10][11]

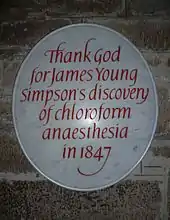

In 1847, Simpson first demonstrated the properties of chloroform upon humans, during an experiment with friends in which he learnt that it could be used to put one to sleep. Dr Simpson and two of his assistants, Dr George Skene Keith (1819-1910) and James Matthews Duncan (1826-1890), used to sit every evening in Dr Simpson's dining room to try new chemicals to see if they had any anaesthetic effect. On 4 November 1847, they decided to try chloroform. On inhaling the chemical they found that a general mood of cheer and humour had set in. But suddenly all of them collapsed only to regain consciousness the next morning. Simpson knew, as soon as he woke up, that he had found something that could be used as an anaesthetic. They soon had Miss Petrie, Simpson's niece, try it. She fell asleep soon after inhaling it while singing the words, "I am an angel!".[12] There is a prevalent myth that the mother of the first child delivered under chloroform christened her child "Anaesthesia"; the story is retailed in Simpson's biography as written by his daughter Eve. However, the son of the first baby delivered by chloroform explained that Simpson's parturient had been one Jane Carstairs, and her child was baptised Wilhelmina. "Anaesthesia" was a nickname Simpson had given the baby.[13]

It was much by chance that Simpson survived the chloroform dosage he administered to himself. If he had inhaled too much and died, chloroform would have been seen as a dangerous substance, which in fact it is.[14] Conversely, if Simpson had inhaled slightly less it would not have put him to sleep. It was his willingness to explore the possibilities of the substance that set him on the road to a career as a pioneer in the field of medicine.

An account of some of Simpson's early uses of ether in childbirth are related by Manchester-based doctor Edmund Lund who visited him in 1847 and can be found in a manuscript held by special collections at the University of Manchester with the reference MMM/12/2.[15]

Antiquarian research

Simpson joined the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland in 1849, and became its vice-president in 1860.[16] He made contributions to both the history of medicine and to archaeology.[17][18] He published several papers on leprosy and syphilis. In both cases he was concerned with the symptoms of the diseases and the relation between historical reports and contemporary cases, and also with the institutions that were set up to care for and segregate the patients.[19][20] Another area he worked on was medicine in Roman Britain[21][22]

Simpson published an early and important work on prehistoric rock art Archaic Sculpturings of Cups, Circles, &c. Upon Stones and Rocks in Scotland, England, & Other Countries.[23] Simpson listed and categorized examples of sculpturings from many parts of the British Isles, often from personal examination, and also included examples from other countries for comparison. Many illustrations are provided. After Simpson's death, a collection of his antiquarian essays was published in two volumes[24]

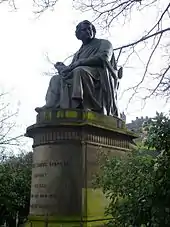

Death and memorials

Simpson was elected President of the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh in 1850[25] and created a Baronet of Strathavon in the County of Linlithgow, and of the City of Edinburgh, in 1866.[26] He died at his home in Edinburgh in May 1870 at the age of 58. A burial spot in Westminster Abbey was offered to his family, but they declined and instead buried him closer to home in Warriston Cemetery, Edinburgh.[27] However, a memorial bust can be found in a niche at Westminster Abbey in London.[28] On the day of Simpson's funeral, a Scottish holiday was declared, including the banks and stock markets, with over 100,000 citizens lining the funeral cortege on its way to the cemetery, while over 1,700 colleagues and business leaders took part in the procession itself.

Dr Alexander Russell Simpson, his nephew, inherited his town house at 52 Queen Street[29] and lived there until his death in 1916, when it was then bequeathed to the Church of Scotland. Since then the building has been through many uses including being requisitioned by the army during the Second World War and being used as a centre for training Sunday School teachers in the 1950s. Today, the town house is the premises of a charity called Simpson House, which provides a counselling service for adults and children affected by alcohol and drug use.[30] There is a plaque on the wall outside to mark the house as having been the home of James Young Simpson from 1845 to 1870.

In 1879 the Edinburgh Royal Maternity and Simpson Memorial Hospital and in 1939 the Simpson Memorial Maternity Pavilion were named in his honour, as is the current Simpson Centre for Reproductive Health at the Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh. The Quartermile development, which consists of the Old Royal Infirmary in Edinburgh, named its main residential street Simpson Loan in his honour.

See also

- Charles Thomas Jackson, claimed to have pioneered the use of diethyl ether

- Crawford Williamson Long, discovered the anaesthetic effect of diethyl ether

- William Thomas Green Morton, pioneered the use of diethyl ether in surgery

- Humphry Davy, first suggested the use of nitrous oxide in 1799

- Horace Wells, in 1844 pioneered the use of nitrous oxide in the US

References

- "Sir James Young Simpson". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 23 August 2013.

- William Haig Miller; James Macaulay; William Stevens (1867). "Sir James Young Simpson, Bart". The Leisure Hour: An Illustrated Magazine for Home Reading. W. Stevens, printer. XVI: 9.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. 25 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 135.

- Biographical Index of Former Fellows of the Royal Society of Edinburgh 1783–2002 (PDF). The Royal Society of Edinburgh. July 2006. ISBN 0-902-198-84-X.

- "Simpson, Sir James Young, first baronet (1811–1870), physician and obstetrician | Oxford Dictionary of National Biography", The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004, doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/25584, retrieved 22 July 2018

- "RMS Notable Members".

- Edinburgh Post Office Directory 1838

- https://www.rcpe.ac.uk/sites/default/files/notablefellows_1.pdf

- Venema, Vibeke (3 December 2013). "Odon childbirth device: Car mechanic uncorks a revolution". BBC World Service. Retrieved 4 December 2013.

- http://www.ph.ucla.edu/epi/snow/anaesthesia59_394_400_2004.pdf

- Blessed Days of Anaesthesia by Stephanie Snow 2009

- Gordon, H. Laing (November 2002). Sir James Young Simpson and Chloroform (1811–1870). The Minerva Group, Inc. p. 108. ISBN 978-1-4102-0291-8. Retrieved 11 November 2011.

- Defalque, Ray J.; Wright, Amos J. J (September 2009). "The Myth of Baby "Anaesthesia". Anesthesiology. 111 (3): 682. doi:10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181b2800f. PMID 19704255.

- T. K. Agasti (1 October 2010). Textbook of Anaesthesia for Postgraduates. JP Medical Ltd. pp. 397–. ISBN 978-93-80704-94-4. Retrieved 15 September 2013.

- "ELGAR: Electronic Gateway to Archives at Rylands :: Display in Full".

- Anderson, Joseph (1911). "Sir James Young Simpson's Work in Archaeology". Edinburgh Medical Journal. 6 (6): 516–522. PMC 5253907.

- Peck, Phoebe (1961). "Doctors afield. Sir James Y. Simpson". New England Journal of Medicine. 265 (10): 486–487. doi:10.1056/NEJM196109072651009. PMID 13733828.

- Turk, J.L. (1994). "Sir James Simpson: leprosy and syphilis". Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. 87 (9): 549–551. PMC 1294776. PMID 7932466.

- Simpson, J.Y. (1841). "Antiquarian Notices of Leprosy and Leper Hospitals in Scotland and England". Edinburgh Medical and Surgical Journal. Part 1; Part 2; Part 3

- Simpson, James Young (1862). Antiquarian notices of syphilis in Scotland in the 15th & 16th centuries. Edinburgh: Edmonston & Douglas.

- Simpson, James Y. "Was the Roman Army provided with medical officers?". In Stuart, John (ed.). Archaeological Essays by the late Sir James Y. Simpson, Volume 2. Edinburgh: Edmonston and Douglas. pp. 196–227.

- Simpson, James Y. "Notices of ancient roman medicine-stamps, etc., found in Great Britain". In Stuart, John (ed.). Archaeological Essays by the late Sir James Y. Simpson, Volume 2. Edinburgh: Edmonston and Douglas. pp. 228–299.

- Simpson, James Young (1867). Archaic Sculpturings of Cups, Circles, &c. Upon Stones and Rocks in Scotland, England, & Other Countries. Edinburgh: Edmonston and Douglas.

- Simpson, James Y. Stuart, John (ed.). Archaeological Essays by the late Sir James Y. Simpson, Volume 2. Edinburgh: Edmonston and Douglas. Volume 1; Volume 2

- Pharand, Michel. Benjamin Disraeli Letters: 1868, Vol. X. p. 97.

- "No. 23064". The London Gazette. 30 January 1866. p. 511.

- For a photograph of his gravesite, see Baskett, T. F. "Edinburgh connections in a painful world". Archived from the original on 20 June 2008. Retrieved 29 September 2008.

- 'The Abbey Scientists' Hall, A.R. p17: London; Roger & Robert Nicholson; 1966

- Edinburgh Post Office Directories

- "Our history - Simpson House CrossReach".

Further reading

- Baillie TW (August 2004). "Hans Christian Andersen's visit to James Young Simpson". Scottish Medical Journal. 49 (3): 112–3. doi:10.1177/003693300404900314. PMID 15462230.

- Ball C (December 1996). "James Young Simpson, 1811–1870". Anaesthesia and Intensive Care. 24 (6): 639. doi:10.1177/0310057X9602400601. PMID 8971309.

- CHALMERS JA (February 1963). "James Young SIMPSON and the "suction-tractor"". The Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology of the British Empire. 70: 94–100. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0528.1963.tb04184.x. PMID 14019913.

- Cohen J (November 1996). "Doctor James Young Simpson, Rabbi Abraham De Sola, and Genesis Chapter 3, verse 16". Obstetrics and Gynecology. 88 (5): 895–8. doi:10.1016/0029-7844(96)00234-7. PMID 8885936.

- Dunn PM (May 2002). "Sir James Young Simpson (1811–1870) and obstetric anaesthesia". Archives of Disease in Childhood: Fetal and Neonatal Edition. 86 (3): F207–9. doi:10.1136/fn.86.3.F207. PMC 1721404. PMID 11978757.

- Eustace DL (November 1993). "James Young Simpson: the controversy surrounding the presentation of his Air Tractor (1848–1849)". Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. 86 (11): 660–3. PMC 1294227. PMID 8258804.

- Gaskell E (May 1970). "Three letters by Sir James Young Simpson". British Medical Journal. 2 (5706): 414–6. doi:10.1136/bmj.2.5706.414. PMC 1700310. PMID 4911888.

- Gordon, B. Laing (1897). Sir James Young Simpson & Chloroform 1811–1870. London: T. Fischer Unwin. OCLC 11397269.

- Gunn AL (March 1968). "James Young Simpson—the complete gynaecologist". The Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology of the British Commonwealth. 75 (3): 249–63. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0528.1968.tb02074.x. PMID 4868187.

- Hill B (May 1970). "Towards the conquest of pain: Sir James Y. Simpson, Bt, M.D. (1811–1870)". The Practitioner. 204 (223): 724–9. PMID 4914462.

- Kellar RJ (October 1966). "Sir James Young Simpson: victo dolore". Journal of the Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh. 12 (1): 1–13. PMID 5341756.

- Kennedy C (October 1966). "Sir James Young Simpson--"the splendid ultimate triumph"". Journal of the Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh. 12 (1): 14–23. PMID 5341755.

- Kennedy C (June 1966). "Sir James Young Simpson--"the splendid ultimate triumph"". The Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology of the British Commonwealth. 73 (3): 364–71. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0528.1966.tb05176.x. PMID 5329917.

- Keys TE (1973). "Sir James Young Simpson (1811–1870)". Anesthesia and Analgesia. 52 (4): 562. doi:10.1213/00000539-197307000-00015. PMID 4577696.

- Kyle RA, Shampo MA (April 1997). "James Young Simpson and the introduction of chloroform anesthesia in obstetric practice". Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 72 (4): 372. doi:10.4065/72.4.372. PMID 9121187.

- Matsuki A (October 1981). "Recent findings in the history of anesthesiology (15)--James Young Simpson" [Recent findings in the history of anesthesiology (15)--James Young Simpson]. Masui (in Japanese). 30 (10): 1142–6. PMID 7035712.

- McGowan SW (December 1997). "Sir James Young Simpson Bart. 150 years on". Scottish Medical Journal. 42 (6): 185–7. doi:10.1177/003693309704200609. PMID 9507600.

- MILLER D (February 1962). "Sir James Young SIMPSON". The Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology of the British Empire. 69: 142–50. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0528.1962.tb00025.x. PMID 14035991.

- Peck P (September 1961). "Doctors afield: Sir James Y. SIMPSON". The New England Journal of Medicine. 265 (10): 486–7. doi:10.1056/NEJM196109072651009. PMID 13733828.

- Pinkerton JH (June 1982). "Sir James Young Simpson: Irish influences". Irish Medical Journal. 75 (6): 183–7. PMID 7050008.

- Simpson, Eve Blantyre, (1896), Sir James Y. Simpson, Edinburgh: Oliphant, Anderson and Ferrier, ("Famous Scots Series").

- Simpson, Myrtle (1972). Simpson, the obstetrician: a biography. London: Gollancz. ISBN 978-0-575-01368-1. OCLC 489148.

- Speert, Harold (1958). Obstetric and Gynecologic Milestones. New York: Macmillan. OCLC 222038266.

- Conacher ID (February 1998). "Why the Y?". British Journal of Anaesthesia. 80 (2): 271–2. doi:10.1093/bja/80.2.271-a. PMID 9602606.

- Secher O (November 1972). "Hans Andersen and James Young Simpson". British Journal of Anaesthesia. 44 (11): 1212–6. doi:10.1093/bja/44.11.1212. PMID 4567093.

- Speert H (October 1957). "Obstetrical-gynecological eponyms: James Young Simpson and his obstetric forceps". The Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology of the British Empire. 64 (5): 744–9. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0528.1957.tb08472.x. PMID 13476274.

- Taylor CW (April 1965). "Lawson Tait – A Grateful Pupil of James Young Simpson". The Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology of the British Commonwealth. 72 (2): 165–71. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0528.1965.tb01411.x. PMID 14273091.

- Waserman M (January 1980). "Sir James Y Simpson and London's "conservative and so curiously prejudiced" Dr Ramsbotham". British Medical Journal. 280 (6208): 158–61. doi:10.1136/bmj.280.6208.158. PMC 1600358. PMID 6986947.

- "Classic articles in colonic and rectal surgery. James Young Simpson 1811–1870". Diseases of the Colon and Rectum. 25 (6): 611–22. September 1982. doi:10.1007/bf02564182. PMID 6749456.

- "James Young Simpson and the conquest of pain". The Medical Journal of Australia. 1 (19): 925–6. May 1970. doi:10.5694/j.1326-5377.1970.tb116701.x. PMID 4912314.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to James Young Simpson. |

- Overview of Sir James Young Simpson

- Papers of Sir James Young Simpson (1811–1870)

- Significant Scots entry

- Who Named It? Entry (well laid out)

- PAPERS OF Sir James Young Simpson The Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh

- Britannica online entry for Sir James

- Entry featuring his gynecological contributions

- West Lothian council memorial to Sir James

- Works by James Young Simpson at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about James Young Simpson at Internet Archive

| Baronetage of the United Kingdom | ||

|---|---|---|

| New creation | Baronet (of Strathavon and the City of Edinburgh) 1866–1870 |

Succeeded by Walter Grindlay Simpson |