Jean-Jacques Chifflet

Jean-Jacques Chifflet (Chiflet) (Besançon, 1588–1660) was a physician, jurist, antiquarian and archaeologist originally from the County of Burgundy (now in France).

_-_MPM_V_IV_031.jpg.webp)

Life

He visited Paris and Montpellier, and travelled in Italy and Germany. By appointment of Philip IV of Spain he was physician to the Brussels court. He played a significant part in the controversy of the 1650s over Peruvian bark in treating malaria, publishing a sceptical pamphlet Pulvis Febrifugus Orbis Americani in 1653[1] after treating Archduke Leopold.[2]

%252C_by_Cornelis_Galle_II.jpg.webp)

At the behest of his employer, Archduke Leopold Wilhelm of Austria, who was then Governor of the Spanish Netherlands, he studied the objects which had been recovered from the tomb of Childeric I in Tournai. In 1655, Chifflet published at the Plantin Press in Antwerp an illustrated report on his findings entitled Anastasis Childerici I. Francorvm Regis, sive Thesavrvs Sepvlchralis Tornaci Neruiorum ... (The Resurrection of Childeric the First, King of the Franks, or the Funerary Treasure of Tournai of the Nervians). This report is today considered to be the world's first scientific archaeological publication.[3] The Chifflet family had engaged a Flemish draughtsman called Jacob van Werden to design the illustrations for various prints included in their publications. Van Werden provided the designs for the illustrations of the Anastasis Childerici I.[4] The illustrations were engraved by Cornelis Galle the Younger.[5] Two of the drawings are still in the Plantin Moretus Museum.[6]

He published the Lilium Francicum, veritate historica, botanica et heraldica illustratum in 1658 at the Plantin Press in Antwerp. This book is a treatise on the heraldic, emblematic, iconographical and historical aspects of the fleur-de-lys.[7] The illustrations in the book were designed by Jacob van Werden. One of the illustrations supports Chifflet's contention that the Frankish king Clovis I used three toads rather than the fleur-de-lys as his royal insignia, which should not be surprising.[6]

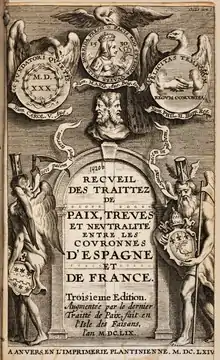

He published various publications on the texts of treaties.[8]

Chifflet's son Jules was a jurist and historian who wrote Breviarium ordinis velleris aurei (Antwerp 1652). Another son, Jean, was a priest and historian who wrote about Pope Joan and published a manuscript of Jean L'Heureux under the title Ioannis Macarii canonici ariensis Abraxas seu Apistopistus; quae est antiquaria de gemmis basilidianis disquistio accedit Abraxas proteus seu multiformis gemmae basilidianae portentosa varietas (Anwerp, Ex officina Plantiniana Balthasaris Moreti, 1657).[9][10]

Jean-Jacques was the nephew of Claude Chifflet.

Works

- Vesontio, civitas imperialis libera, Sequanorum metropolis, Leiden, 1618

- Portus lecius Julius Caesaris, 1627, (locating the Portus Lecius mentioned by Julius Caesar at Mardick)

- Blason des chevaliers de la Toison d'Or, 1632, on the Knights of the Golden Fleece

- Recueil des Traittez de Paix, Treves et Neutralité entre les couronnes d'Espagne et de France (1643)

- Pulvis Febrifugus Orbis Americani (1653) Available from Google Books (accessed 21 Feb. 2015).

- Anastasis Childerici I. Francorvm Regis, sive Thesavrvs Sepvlchralis Tornaci Neruiorum ... , 1655, from Internet Archive. Scanned from a volume in the collection of Biblioteca Complutense Ildefonsina.

- Lilium Francicum, veritate historica, botanica et heraldica illustratum in 1658 at the Plantin Press

- Political writings upholding the rights of the House of Austria and Burgundy against France

Notes

- Cinchona. U. S. Cinchona, Cinch. [Peruvian Bark, Yellow Peruvian Bark]. Cinchona Rubra, Red Cinchona. | Henriette's Herbal Homepage

- Andreas-Holger Maehle, Drugs on Trial: Experimental Pharmacology and Therapeutic Innovation in the Eighteenth Century (1999), pp. 226-9.

- Peter S. Welles, Barbarians to Angels: The Dark Ages Reconsidered (2009), p. 51.

- Frank van den Wijngaert, De botanische teekeningen in het museum Plantin-Moretus in: "De Gulden Passer". Jaargang 25. De Nederlandsche Boekhandel, Antwerpen 1947, p. 11

- Jean-Jacques Chifflet, Childerici I, Francorum regis, sive Thesaurus sepulchralis Tornaci Nerviorum effossus et commentario illustratus, Antverpiae : ex off. Plantiniana B. Moreti, 1655

- Sven Dupré, Christoph Herbert Lüthy, Silent Messengers: The Circulation of Material Objects of Knowledge in the Early Modern Low Countries, LIT Verlag Münster, 2011, p. 40

- Karen Lee Bowen, The illustration of books published by the Moretuses, Museum Plantin-Moretus, 1997, pp. 169-170

- David C. Douglas, English Scholars (1939), p.290.

- Emmanouēl Rhoïdēs, La papesse Jeanne, roman historique, précédé d'une étude historique, traduit, E. Capiomont et V. Renault, 1878, p. 54

- Ioannis Macarii canonici ariensis Abraxas seu Apistopistus; quae est antiquaria de gemmis basilidianis disquistio accedit Abraxas proteus seu multiformis gemmae basilidianae portentosa varietas, Antwerp, Ex officina Plantiniana Balthasaris Moreti, 1657

References

- Bouillet, Marie-Nicolas; Chassang, Alexis (1901). Dictionnaire universel d'histoire et de géographie. Paris, France: Hatchette et Cie. p. 408.

External links

Media related to Jean-Jacques Chifflet at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Jean-Jacques Chifflet at Wikimedia Commons- Works by or about Jean-Jacques Chifflet at Internet Archive