Jeanne Paquin

Jeanne Paquin (French pronunciation: [ʒan pakɛ̃]) (1869–1936) was a leading French fashion designer, known for her resolutely modern and innovative designs. She was the first major female couturier and one of the pioneers of the modern fashion business.[1]

Jeanne Paquin | |

|---|---|

Madame Paquin | |

| Born | Jeanne Marie Charlotte Beckers 1869 Saint-Denis, France |

| Died | 1936 Paris, France |

| Occupation | Couturière, fashion designer |

Label(s) | Maison Paquin |

| Spouse(s) | Isidore Rene Jacob dit Paquin |

Early life

Jeanne Paquin was born Jeanne Marie Charlotte Beckers in 1869. Her father was a physician.[1] She was one of five children.[2]

Sent out to work as a young teenager, Jeanne trained as a dressmaker at Rouff (a Paris couture house established in 1884 and located on Boulevard Haussmann[3][4]). She quickly rose through to ranks becoming première, in charge of the atelier.[1]

In 1891, Jeanne Marie Charlotte Beckers married Isidore René Jacob, who was also known as Paquin. Isidore owned Paquin Lalanne et cie, a couture house which had grown out of a menswear shop in the 1840s. The couple renamed the company Paquin and set about building the business.[1]

The House of Paquin under Jeanne

In 1891, Jeanne and Isidore Paquin opened their Maison de Couture at 3 Rue de la Paix in Paris, next to the celebrated House of Worth.[1][5] Jeanne was in charge of design, while Isidore ran the business.[6]

Initially, Jeanne favored the pastels in fashion at the time. Eventually, she moved on to stronger colors like black and her signature red.[1] Black had been traditionally the color of mourning. Jeanne made the color fashionable by blending it with vividly colorful linings and embroidered trim.[7]

Jeanne Paquin was the first couturier to send models dressed in her apparel to public events such operas and horse races for publicity.[5][8][9] Paquin also frequently collaborated with the illustrators and architects such as Léon Bakst, George Barbier, Robert Mallet-Stevens, and Louis Süe.[1][9] She was also known to collaborate with the theatre, in a time when other houses rejected collaboration. In 1913, a New York Times reporter described Jeanne as "the most commercial artist alive".[1]

A London branch of The House of Paquin was opened in 1896 and the business became a limited company the same year.[10] This shop employed a young Madeleine Vionnet.[1] The company later expanded with shops in Buenos Aires and Madrid.[6][11]

In 1900, Jeanne was instrumental in organizing the Universal Exhibition and she was elected president of the Fashion Section.[5][11] Her designs were featured prominently at the Exhibition[11] and Jeanne created a mannequin of herself for display.[1]

Isidore Paquin died in 1907 at the age of 45, leaving Jeanne a widow at 38. Over 2,000 people attended Isidore's funeral. After Isidore's death, Jeanne dressed mostly in black and white.[1]

In 1912, Jeanne and her half-brother opened a furrier, Paquin-Joire, on Fifth Avenue in New York City.[11] The same year, Jeanne signed an exclusive illustration contract with La Gazette du Bon Ton. La Gazette du Bon Ton featured six other leading Paris designers of the day – Louise Chéruit, Georges Doeuillet, Jacques Doucet, Paul Poiret, Redfern & Sons, and the House of Worth.[12]

In 1913, Jeanne accepted France's prestigious Legion d’Honneur in recognition of her economic contributions to the country – the first woman designer to receive the honor.[6] A year later, Jeanne toured the United States. For five dollars, attendees saw The House of Paquin's latest designs. Despite the high ticket price, the tour sold out.[11]

During World War I, Jeanne served as president of the Chambre Syndicale de la Couture.[13] She was the first woman to serve as president of an employers syndicate in France.[14]

At its height, the House of Paquin was so well known that Edith Wharton mentioned the company by name in The House of Mirth.[7]

At a time when couture houses employed 50 to 400 workers, the House of Paquin employed up to 2,000 people at its apex.[13] The Queens of Spain, Belgium, and Portugal were all customers of Paquin. So were courtesans such as La Belle Otero and Liane de Pougy.[1][12]

The House of Paquin (1920–1956)

When Jeanne Paquin retired in 1920, she passed responsibility to her assistant Madeleine Wallis. Wallis remained as house designer for Paquin until 1936, the same year that Jeanne Paquin died. Between 1936 and 1946, the Spanish designer Ana de Pombo, Wallis's assistant, was house designer. In 1941, de Pombo left, and her assistant, Antonio del Castillo (1908–1984) took over as head designer. In 1945 del Castillo left Paquin to become a designer for Elizabeth Arden, and would later become head designer for the house of Lanvin. He was succeeded by Colette Massignac, who was tasked with the challenge of keeping Paquin going during the post-War years, when new designers such as Christian Dior were receiving greater publicity and attention. In 1949, the Basque designer Lou Claverie became head designer at Paquin, until 1953, when he was succeeded by a young American designer, Alan Graham. However, Graham's understated designs failed to reinvigorate the brand of Paquin, and the Paris house closed on 1 July 1956.[15]

Gallery

1903. Chincilla fur stole and muff by Paquin.

1903. Chincilla fur stole and muff by Paquin. 1906. 'Five Hours at Paquin' by Henri Gervex

1906. 'Five Hours at Paquin' by Henri Gervex 1907. 'La Rue de la Paix' by Jean Béraud. Paquin's salon is on the far right.

1907. 'La Rue de la Paix' by Jean Béraud. Paquin's salon is on the far right. Caricature of Jeanne Paquin by Sem, 1910

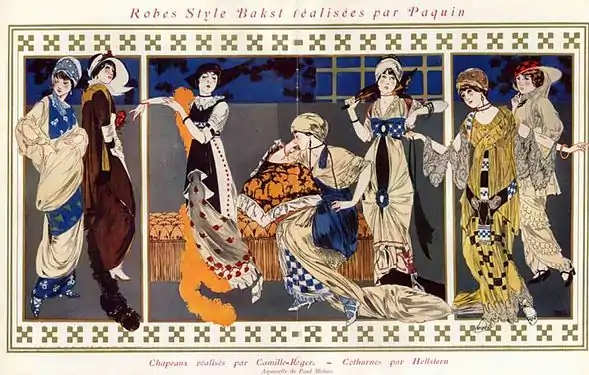

Caricature of Jeanne Paquin by Sem, 1910 1912 dresses designed by Léon Bakst for Paquin

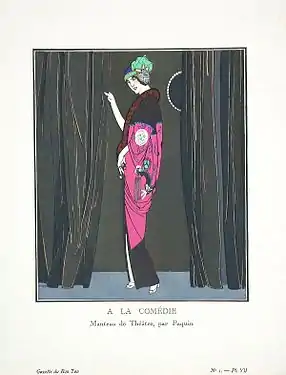

1912 dresses designed by Léon Bakst for Paquin 1913 theatre coat

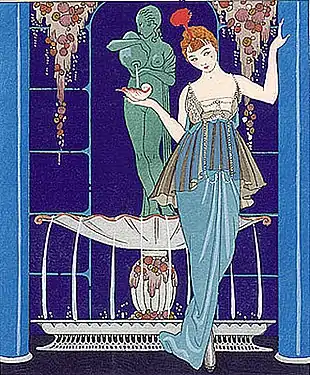

1913 theatre coat 1914 evening dress

1914 evening dress 1915-17 evening dress

1915-17 evening dress 1926 chiffon evening dress

1926 chiffon evening dress 1939 flamenco style evening dress by Ana de Pombo for Paquin[16]

1939 flamenco style evening dress by Ana de Pombo for Paquin[16]

References

- Polan, Brenda; Tredre, Roger (1 October 2009). The Great Fashion Designers. Berg. p. 17. ISBN 9780857851741.

Jeanne%20Paquin.

- CHARLES., DAWBARN (2015). MAKERS OF NEW FRANCE (CLASSIC REPRINT). [S.l.]: FORGOTTEN BOOKS. ISBN 978-1330761991. OCLC 982520407.

- Lipovetsky, Gilles (2002). Empire de L'éphémère. Princeton University Press. p. 57. ISBN 9780691102627.

- Fukai, Akiko (2002). Fashion: The Collection of the Kyoto Costume Institute: S History from the 18th to the 20th Century. p. 719. ISBN 9783822812068.

- "Fashion Drawing and Illustration in the 20th Century". Victoria and Albert Museum. Victoria and Albert Museum. 13 August 2013. Retrieved 15 September 2015.

- "Jeanne Paquin". FIDM Museum Blog. Retrieved 15 September 2016.

- Joslin, Katherine (1 January 2009). Edith Wharton and the Making of Fashion. UPNE. ISBN 9781584657798.

- Nudelman, Zoya (10 March 2016). The Art of Couture Sewing. Bloomsbury Publishing USA. ISBN 9781609018313.

- Dirix, Emmanuelle (1 March 2016). Dressing the Decades: Twentieth-Century Vintage Style. Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300215526.

- "Paquin, Limited" (Page 4). The Times (London, Greater London, England) 23 Nov 1896, Mon • Page 4. 23 November 1896. Retrieved 25 November 2016.

- F, José Blanco; Hunt-Hurst, Patricia Kay; Lee, Heather Vaughan; Doering, Mary (23 November 2015). Clothing and Fashion: American Fashion from Head to Toe. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9781610693103.

- Stewart, Mary Lynn (4 March 2008). Dressing Modern Frenchwomen: Marketing Haute Couture, 1919–1939. JHU Press. ISBN 9780801888038.

- Calahan, April (3 November 2015). Fashion Plates: 150 Years of Style. Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300212266.

- Véronique Pouillard, "Managing Fashion Creativity: The History of the Chambre Syndicale de la Couture Parisienne During the Interwar Period," Economic History Research(2015)

- Milford-Cottam, Daniel (2 June 2015). "Paquin: Parisian Fashion Designs 1897–1954". The Factory Presents. Victoria and Albert Museum. Retrieved 26 September 2016.

- "Evening dress design, Summer 1939, Ana de Pombo for Paquin". V&A Search the Collections. Victoria and Albert Museum. Retrieved 26 September 2016.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Jeanne Paquin. |