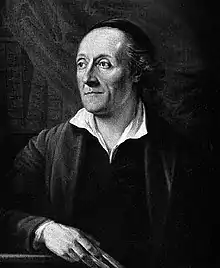

Johann Kaspar Lavater

Johann Kaspar (or Caspar) Lavater (Alemannic German: [ˈlɒːv̥ɒtər];[1] 15 November 1741 – 2 January 1801) was a Swiss poet, writer, philosopher, physiognomist and theologian.

Early life

Lavater was born in Zürich, and was educated at the Gymnasium there, where J. J. Bodmer and J. J. Breitinger were amongst his teachers.

Corruption fighter

At barely twenty-one years of age, Lavater greatly distinguished himself by denouncing, in conjunction with his friend Henry Fuseli the painter, an iniquitous magistrate, who was compelled to make restitution of his ill-gotten gains.

Zwinglian

In 1769 Lavater took Holy Orders in Zurich's Zwinglian Church, and officiated until his death as deacon or pastor in churches in his native city. His oratorical fervor and genuine depth of conviction gave him great personal influence; he was extensively consulted as a casuist, and was welcomed with enthusiasm on his journeys throughout Germany. His writings on mysticism were widely popular as well.

In the same year (1769), Lavater tried to convert Moses Mendelssohn to Christianity, by sending him a translation of Charles Bonnet's Palingénésie philosophique, and demanding that he either publicly refute Bonnet's arguments or convert. Mendelssohn refused to do either, and many prominent intellectuals took Mendelssohn's side, including Lichtenberg and Herder.

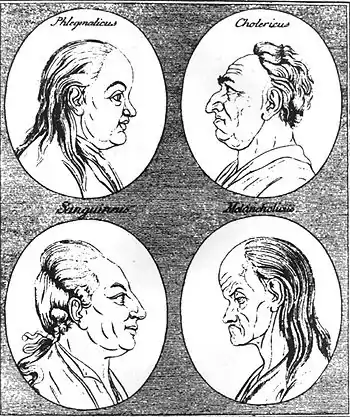

Physiognomy

Lavater is most well known for his work in the field of physiognomy, Physiognomische Fragmente zur Beförderung der Menschenkenntnis und Menschenliebe, published between 1775 and 1778. He introduced the idea that physiognomy related to the specific character traits of individuals, rather than general types.[2]

Lavater is attributed with catalysing a golden age for silhouettes through this work in physiognomy. According to him, the character of a person could be elucidated through examining their “lines of countenance”. The most accurate of readings were facilitated by the tracing of a profile outline portrait. This contour line could be filled with black or cut from the white paper and placed over a black backing. More often, the silhouette was simply cut from black paper. In the chapter “On Shades”, Lavater wrote, “What can less the image of a living man be than a shade? Yet how full of speech! Little gold, but the purest." [3]

The fame of this book, which found admirers in France and England as well as Germany, rests largely upon the handsome style of publication and the accompanying illustrations.

The two principal sources from which Lavater developed his physiognomical studies were the writings of the Italian polymath Giambattista della Porta, and the observations made by Sir Thomas Browne in his Religio Medici (translated into German in 1748 and praised by Lavater).

Poet

.jpg.webp)

As a poet, Lavater published Christliche Lieder (1776–1780) and two epics, Jesus Messias (1780) and Joseph von Arimathia (1794), in the style of Klopstock. More relevant to the religious temperament of Lavater's times are his introspective Aussichten in die Ewigkeit (4 vols. 1768-1778), Geheimes Tagebuch von einem Beobachter seiner selbst (2 vols., 1772–1773), and Pontius Pilatus, oder der Mensch in allen Gestalten (4 vols., 1782–1785).

Goethe

From 1774 on, Goethe was intimately acquainted with Lavater, but later had a falling out with him, accusing him of superstition and hypocrisy.

Blake

In 1788 William Blake annotated Lavater's Aphorisms of Man.[4][5] Lavater published 632 aphorisms in all. Blake considered the following aphorism to be an excellent example of an aphorism. "40. Who, under pressing temptations to lie, adheres to truth, nor to the profane betrays aught of a sacred trust, is near the summit of wisdom and virtue."

Last days

During his later years, Lavater's influence waned, and he incurred considerable ridicule due to his vanity. His conduct during the French occupation of Switzerland brought about his death. On the taking of Zürich by the French in 1799, Lavater, while trying to appease the aggressors, was shot by an infuriated grenadier; he died over a year later, after protracted sufferings borne with great fortitude.

The Swiss artist and illustrator, Warja Honegger-Lavater, was a direct descendant of Johann Kaspar Lavater.

Works

- Vermischte Schriften (2 vols., 1774–1781)

- Kleinere prosaische Schriften (3 vols., 1784–1785)

- Nachgelassene Schriften (5 vols., 1801–1802)

- Sämtliche Werke (poems only; 6 vols., 1836–1838)

- Ausgewählte Schriften (8 vols., 1841–1844).

References

- "How to pronounce Lavater". Forvo.com. Retrieved 2 October 2018.

- J. Arianne Baggerman; Rudolf M. Dekker; Michael James Mascuch (22 June 2011). Controlling Time and Shaping the Self: Developments in Autobiographical Writing Since the Sixteenth Century. BRILL. p. 250–. ISBN 978-90-04-19500-4.

- Aphorisms of Man

- Annotations to Lavater's Aphorisms on Man

- The Faces of physiognomy : interdisciplinary approaches to Johann Caspar Lavater. Edited by Ellis Shookman. Columbia, SC : Camden House, 1993. (ISBN 1879751518)

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Johann Kaspar Lavater |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Johann Kaspar Lavater. |