John A. Wilson (sculptor)

John Albert Wilson (1877 – December 8, 1954) was a Canadian sculptor who produced public art for commissions throughout North America. He was a professor in the School of Architecture at Harvard University for 32 years. He is most famous for his American Civil War Monuments: the statue on the Confederate Student Memorial (Silent Sam) on the campus of the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, and the Washington Grays Monument (Pennsylvania Volunteer) in Philadelphia.

John Albert Wilson | |

|---|---|

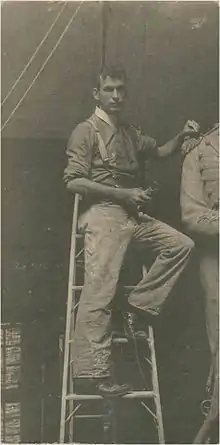

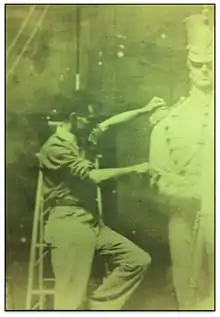

John A. Wilson sculpting Washington Grays Monument (1907) | |

| Born | 1877 |

| Died | December 8, 1954 (aged 77) |

| Nationality | Canadian |

| Known for | Sculpture |

Notable work | Silent Sam, Daniel A. Bean, Washington Grays Monument |

| Movement | American Renaissance |

| Awards | Kimball Prize |

Renowned sculptor and art historian Lorado Taft wrote of the latter work, "No American sculpture, however, has surpassed the compelling power which John A. Wilson put into his steady, motionless 'Pennsylvania Volunteer'."[1] Wilson created his studio (the "Waban Studio") at Chestnut Hill, Massachusetts. Walter Gropius , known as a pioneering master of modern architecture, said the studio "is the most beautiful in the world."[2]

Life and career

He was born in New Glasgow, Nova Scotia (Potter's Brook), son of John and Annie (Cameron) Wilson. His grandfather was a stonemason who emigrated from Beauly, Scotland.[3] Wilson attended New Glasgow High School. At the age of fifteen he created a sculpture of a lion out of freestone (1891).[4]

In 1896, at age nineteen, he went to Boston to study art. During the day he attended the Cowles Art School of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, where he studied drawing and painting under Bela Pratt. He worked in the evenings as an usher in a theatre, and he worked on the weekends as a professional boxer at the Boston Athletic Club. While at the Fine Arts school, Wilson displayed his work The Crawling Panther (also known as the Stalking Panther) at the Boston Art Club (1905). He received attention from The Boston Globe and Boston Herald newspapers for this work. The latter wrote that it was a "powerful work by a very young man".[5] He graduated from the School of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston in 1905. He next worked as an assistant to Henry Kitson.[6]

Beginning in 1906, Wilson taught classes for the Copley Society of Art in Boston.[7] He joined the board of directors in 1913 and taught there for 32 years until 1945. In 1927, he was named Director of Classes.[8] One of his students at the Society was John Hovannes (1900-1973).[9]

In 1917, Wilson started to teach at Harvard University when the scholarly Abbott Lawrence Lowell was president. He was appointed Instructor in Modelling, School of Architecture, Harvard University. He served at Harvard for 32 years, retiring in 1949.[10] During his tenure at the Copley Society and Harvard, Wilson also taught in various other places.

Wilson taught for 5 years at the Worcester Art Museum (1917–22), where he would complete the Hector Monument (1923) with his student Evangeline Eells Wheeler.[11] He taught one year at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (1921–22),[12] three years at Children's Walker School, and three years at Bradford College. He also taught at his own studio in Chestnut Hill.

In 1913, he had built his home and his "Waban Studio" at 101 Waban Hill Rd, Chestnut Hill, where he lived for 36 years. After 50 years, when he retired, Wilson returned in 1949 to New Glasgow, Nova Scotia. He lived there for five years at East River, Potter's Bridges, New Glasgow.

Death

Wilson died on December 8, 1954 at Aberdeen Regional Hospital, New Glasgow. Before his passing, he donated property to the Aberdeen Hospital. It was later replaced by Glen Haven Manor now stands. A plaque in his honor hangs in the Hospital's cafeteria.[13] He is buried in the Riverside Cemetery, New Glasgow, Nova Scotia.

Works

American Civil War

The year after Wilson graduated from School of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (1905), he received his first major recognition when he was commissioned by the State of Pennsylvania to make the Washington Grays Monument in Philadelphia to the men who served in the American Civil War.[14]

In 1909, Wilson's soldier's monument for all soldiers of war was unveiled on Dudley's Town Common (in front of the First Congregational Church), Dudley, Massachusetts. A crowd of 1200 was in attendance.[15] Four-sided and capped with the sculpture of an American eagle, the multiwar memorial has inscriptions for the American Revolution: "To the memory of Dudley's Heroes who bore arms to found an Independent Nation - 1776"; the American Civil War: "Her Patriots of 1861-1865 who offered their lives to Preserve this Union"; and the Spanish–American War/Philippine–American War: "her soldiers in the Spanish-Philippines War, 1878."

In 1909, Wilson created the "Massachusetts Monument" in the Baton Rouge National Cemetery. The commemorative monument on its grounds, was erected to honor Massachusetts sailors and soldiers who died in Civil War battles in the Gulf region. The granite monument is inscribed with the names of the Infantries and Light Batteries that served in the Gulf theater of operations. Massachusetts Governor Ebenezer Sumner Draper attended the proceedings.

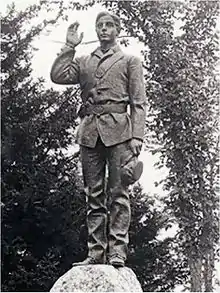

In 1911, he created a statue of Private Daniel A. Bean of Brownfield, Maine, 11th Maine Volunteer Infantry Regiment. Major Sylvanus Bangs Bean[16] served with the 11th Maine Regiment along with his son, Daniel A. Bean. Daniel was killed in Hampton, Virginia as a result of being shot in both thighs during the war. Daniel died before his father Sylvanus could see him at the field hospital. Daniel died on 06/06/1864 and is buried at Plot: D 2820, Hampton National Cemetery, City of Hampton, Virginia, USA. The statue of Daniel Bean stands in Brownfield, Maine, where the roads to Hiram and Denmark diverge. Of all the Civil War memorials erected by Maine towns, this remarkable monument was the only one cast in the image of a real person. The absence of weapons distinguishes it even further. The boy stands as he would have on his last day at home, taking the Oath of Induction.[17]

In 1913, Wilson was commissioned by the North Carolina Chapter of the United Daughters of the Confederacy to make the Confederate Monument, later known as Silent Sam, as a monument to the students of University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill who served in the Confederate forces. It was the first major work Wilson created in his new "Waban Studio". Although this statue, unlike that of Bean, is armed, it has been described as "silent" because the soldier has no cartridge box on his belt so he cannot fire his gun.[18] In August 2018 the statue was torn down by protestors; as of February 2020 it is not on display and no decision has been made on its future disposition.[19]

Firemen's Memorial, Boston

In 1909, Wilson created Firemen's Memorial (Boston) for the Firemen's Lot at Forest Hills Cemetery, Jamaica Plain, Boston.[20] Each year on the second Sunday in June, memorial services sponsored by the Charitable Association of the Boston Fire Department are held at the Firemen's Memorial at Forest Hills Cemetery in order to pay tribute to deceased members so they would be assured of a decent and final resting place and they would not necessarily end up in Pauper's Field.

On a lofty granite base a larger-than-life fireman in bronze, attired for service but in a moment of contemplation. On each side of the pedestal were set bronze plaques, 3 ft. by 4 ft., depicting the life of a fireman in the spirit of a renowned set of Currier & Ives prints. Shown in vivid bas-relief were horse-powered equipment and men en route to their duty. The plaque on the rear of the statue pictures a nineteenth century pumper as it would have looked between fires in the firehouse with no horses, men, or background. The memorial was dedicated in grand style on June 14, 1909. On that day, set aside in all the state for past firemen, the memorial was dedicated in a ceremony partially presided over by John F. Fitzgerald, grandfather of John F. Kennedy and former mayor of Boston.[21]

Harvard University

While teaching at Harvard University (1917–46), Wilson made numerous sculptures of figures connected to the University. Perhaps the best known figure is the Janitor in the Fogg Museum entitled "George". Articles with a photo of George Archambeau were printed in both Time Magazine and The New York Times when the bust was unveiled in September 1932.[22] Wilson also made two busts of William Crowninshield Endicott, one in the Fogg Museum and the other in Harvard University Law School (1932). Wilson also made two busts of Harvard president Abbott Lawrence Lowell. One is a marble bust in the Faculty Room, University Hall (Harvard University) (1930)[23] and the other is a bronze bust at Lowell House Residence, Harvard University[24] Wilson also made the mould for the commorative punch bowl and dishes for Harvard University's tercentennial (1936).[25]

One of Wilson's most famous Harvard graduates was sculptor Wheeler Williams who wrote to him,

- How very lucky I was to find myself in your class in the basement of Robison Hall. If it had not been for that, classes at the Copley Society of Art and Sundays in your studio, I fear my life long dream of being a sculptor would not have materialized. Where anybody today could get the sound training you gave us, I have no idea.[26]

Nova Scotia

The Nova Scotia monuments were made in the same year (1923). The Hector Pioneer was made in the Worcester Art Museum. Wilson's assistant for the work was Evangeline (Eells) Wheeler. The sculpture was unveiled 17 July 1923 on the 150 Anniversary of the arrival of the ship Hector. The Governor General of Canada Field Marshal Julian Byng, 1st Viscount Byng of Vimy led the proceedings.

The Lion Series

Wilson made a series of nine lions in freestone early in his career. The location of six of these lions is unknown. Three of these lions remain in Pictou County, Nova Scotia.[27] One of the lions is on the grounds of the Lionstone Inn, an establishment named after the sculpture.[28] The other two lions are at the Carmichael-Stewart House Museum. One of these Wilson made at the age of 15 before he moved to Boston (1891). The other lion at the museum Wilson made while studying in Boston (1902). The sculpture representing Great Britain in South Africa during the Boer War and was noted as being "an admirable piece of modelling from one of his age".[29] In March 1902 the Royal Canadian Academy of Arts accepted this lion for its annual exhibition in Montreal.[30]

Other

- Monument on the American Civil War Antietam National Battlefield, Maryland

- Major Henry Gustavus Dorr, made at Grundmann Studios (1915)

- William Crowninshield Endicott at the Harvard University Law School (1932)[31]

- Death mask of Admiral William Sims

- Soldier's monument Dudley, Massachusetts

- Massachusetts Monument, Baton Rouge National Cemetery, Baton Rouge, Louisiana

- Abbott Lawrence Lowell, Marble Bust, Faculty Room, University Hall (Harvard University) (1930)[32]

- Abbott Lawrence Lowell, Bronze Bust, Lowell House, Harvard University[33]

- "Dancing Figure", Algonquin Club, Boston

- Symbolic Panels, Brookline High School, Boston (1923)

- "Panther"

- "Stalking Panther", Boston Art Club Exhibition (1905)

- "The Chase"

- "Goat", Sandy, Poland Spring, Maine

- Alexander Forrester tablet, Nova Scotia Community College, Truro, Nova Scotia[34] (c. 1923)

Image gallery

Confederate soldier Silent Sam, North Carolina

Confederate soldier Silent Sam, North Carolina Massachusetts Monument, Baton Rouge National Cemetery (1909)

Massachusetts Monument, Baton Rouge National Cemetery (1909)

Harvard University Commemorative Pieces - Tercentennial (1936)

Harvard University Commemorative Pieces - Tercentennial (1936) Hector Pioneer (1923) by John Wilson, Pictou, Nova Scotia

Hector Pioneer (1923) by John Wilson, Pictou, Nova Scotia Alexander Forrester Monument (c.1923), NSCC, Truro, Nova Scotia[35]

Alexander Forrester Monument (c.1923), NSCC, Truro, Nova Scotia[35]

References

Texts

- Eric Barker. "John Wilson: Famous Nova Scotian from N.G." The Evening News, New Glasgow, N.S., 3 May 1972:

- James Cameron. More About New Glasgow. 1974. pp. 191–195

- Clyde MacDonald. More Notable Pictonians. 2004. pp. 48–85.

- G.E.G. MacLaren. "Nova Scotia's First Sculpture[: John A. Wilson]". Nova Scotia Historical Quarterly, Vol. #3:2 (1973): 4 pp.

Endnotes

- Lorado Taft. The History of American Sculpture. 1925. p. 570 (first published 1903)

- George MacLaren. "Nova Scotia's First Sculpture: John A. Wilson", Nova Scotia Historical Quarterly, Vol. #3:2 (1973), p. 119

- MacDonald, p. 48

- Eric Barker, "John Wilson: Famous Nova Scotian from N.G.", The Evening News, New Glasgow, N.S., May 3, 1972.

- Nova Scotia Archives and Records Management. John Wilson Scrapbook. Exhibition dates: January 6 - February 4, 1905.

- George MacLaren. "Nova Scotia's First Sculpture: John A. Wilson]", Nova Scotia Historical Quarterly, Vol. #3:2 (1973): p. 117

- Boston Evening Transcript, December 7, 1912.

- George MacLaren. "Nova Scotia's First Sculpture[: John A. Wilson]". Nova Scotia Historical Quarterly, Vol. #3:2 (1973): p. 118

- John Hovannes profile, papillongallery.com; accessed February 10, 2015.

- John Wilson: Famous Nova Scotian from N.G. by Eric Barker. The Evening News, New Glasgow, N.S., May 3, 1972.

- Profile, findagrave.com; accessed February 10, 2015.

- MacDonald, p. 51

- "John Wilson: Famous Nova Scotian from N.G." by Eric Barker. The Evening News, New Glasgow, N.S., May 3, 1972:

- George MacLaren. "Nova Scotia's First Sculpture: John A. Wilson", Nova Scotia Historical Quarterly, Vol. #3:2 (1973), p. 118.

- Worcester Daily Telegram July 6, 1909

- Sylvanus Bean

- MacDonald, p. 60; One writer suggested the figure is holding his cap in one hand and waving a timid goodbye with the other. (See http://www.concordmonitor.com/article/silent-witness-to-war?SESS87347230340d3304ac4a819ccf549544=google&page=full%5B%5D )

- .Silent Sam (Civil War Monument), The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Virtual Tour; retrieved March 1, 2008.

- Boston's Fire Trail: A Walk Through the City's Fire and Firefighting History By Boston Fire Historical Society, Paul A. Christian, 2007. p. 109

- Profile Archived 2012-12-03 at the Wayback Machine, jphs.org; accessed February 10, 2015.

- "Archambeau Bust". Time Magazine 19 September 1932, p. 32; "Bust of George" The New York Times. 9 September 1932, p. 21

- Henry Aaron Yeomans, Walter P. Metzger Abbott Lawrence Lowell, 1856-1943 1977. pp. 361

- Henry Aaron Yeomans, Walter P. Metzger Abbott Lawrence Lowell, 1856-1943 1977. pp. 361

- MacLaren, p. 120. 1000 copies were made by Wedgewood, England

- MacDonald, p. 83

- MacDonald, p. 51-52

- Lionstone Inn

- Artists in Nova Scotia. Collections of the Nova Scotia Historical Society, 1914, pp. 156-157

- Royal Canadian Academy Annual Exhibition: (Montreal, March 1902) "Annual Exhibition of the Royal Canadian Academy", Montreal Daily Herald, March 22, 1902, page 2.

- http://collections.si.edu/search/results.htm?q=record_ID:siris_ari_19191 Formerly located at the Fogg Museum, Harvard University

- Henry Aaron Yeomans, Walter P. Metzger Abbott Lawrence Lowell, 1856-1943 1977, p. 361

- Henry Aaron Yeomans, Walter P. Metzger Abbott Lawrence Lowell, 1856-1943 1977. pp. 361

- Profile, biographi.ca; accessed February 10, 2015.

- History of the Forrester Memorial

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to John A. Wilson (sculptor). |