John Brown's raiders

On Sunday night, October 16, 1859, the abolitionist John Brown led a motley band of 22 in a raid on the federal arsenal at Harpers Ferry, Virginia (since 1863, West Virginia). Most were much younger than him. His intention was to seize the arms there, as many as could be taken, and use them to arm the enslaved. In the Appalachian mountains there would be an anti-slavery state of sorts, encouraging the enslaved to flee their owners, as far south as Georgia. Brown expected that a large number of the enslaved would join the revolt, but only a handful did.

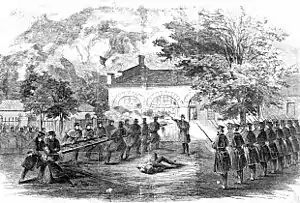

In the short term, the raid was a total failure. Brown and his men quickly captured the armory, which had only one watchman, and took over 60 residents of Harpers Ferry hostage as they arrived for work. Militia summoned from neighboring towns took over both bridges, thus cutting off escape, and by noon Monday forced Brown and his party to take refuge in the fire engine house of the armory, a sturdy building later known as John Brown's Fort. The militia freed most of the hostages, leaving only the handful in the engine house. Brown's party held out until Tuesday morning, when a company of Marines, led by Col. Robert E. Lee, quickly broke down the doors to the engine house and took the surviving raiders captive. The 7 survivors, including John Brown, were quickly tried for treason, murder, and inciting a slave revolt, and were convicted and executed by hanging, in the Jefferson County seat of Charles Town. John Brown was the first person executed for treason in the history of the United States.

However, the raid and the following trials were extensively covered by the press. "The country had not been so excited about anything in twenty years."[1]:362 Historians frequently credit the raid not for starting the Civil War, but for providing the spark that lit the waiting bomb, or as Brown would have put it, causing "the volcano beneath the snow" to erupt. Brown thought that without violence, slavery in the United States would never end. John Brown's raid was the beginning of the end of American slavery.[2]

The people of Virginia were furious, outraged at this attempt to get their allegedly happy enslaved to revolt. They took out their anger at any opportunity. Watson Brown was shot when he left the engine house carrying a white flag. William Thompson was shot on the bridge and taken to the hotel parlor; armed men came in, dragged him out, and threw him over the bridge into the river, firing as he fell. The owner of the hotel did not want the carpet ruined by shooting him there.[3]

The bodies of the slain lay in the streets, on the river banks, or wherever they fell. Dangerfield Newby's body, which lay in the street from 11 AM Monday, when he was killed, until Tuesday afternoon, was partially eaten by hogs,[4] and his ears were cut off as souvenirs. The bodies of two of the men killed were taken by medical students from Winchester Medical College, and the remainder were dragged into a "gruesome pile", boxed, and dumped in a pit.

Sources of information

The only raiders whose stories are relatively well known are those processed through the Virginia legal system and publicly executed, although no centralized record was kept of what happened to their corpses. Three of them have been the subject of recent (2015–2020) books: John Edwin Cook,[5] whose testimony was quickly published in a pamphlet to raise money for one of the victims,[6] John Anthony Copeland,[7] and Shields Green,[8]

As for the others, they had come from all over the country and Canada, and were from diverse social classes, from fugitive slaves to the comfortably middle class. Given the chaos which succeeded the raid, with many dead or dying, some unidentified corpses taken to a nearby medical college for instructional use, some raiders fleeing and being captured and others fleeing successfully, and unidentified bodies drifting down the Potomac River, there is much confusion in the details about who was involved and what happened to them. More information is available about the white participants than the Blacks, who were treated far more roughly from beginning to end.[9]

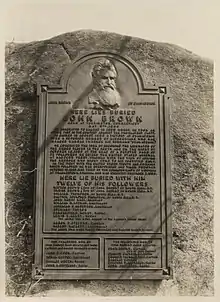

As a result different sources can have differing pieces of information, or sometimes misinformation, about who was involved. As explained below, some bodies were not identified until many years afterward. The bronze plaque above the graves at the John Brown Farm itself contains errors. (It reports that the remains of Jerry Anderson are buried there, which is not correct, and it invents an otherwise unknown John Anderson, a negro who escaped.)

Robert E. Lee's report, October 19; 1859

Then-Colonel Robert E. Lee, in charge of the Marines who quickly broke down the engine house door and ended the raid, took the trouble to learn their identities. In his report, first published by the Senate investigative committee,[10] he provides the name and home state of each of the raiders. He adds the rank in Brown's organization: captain, lieutenant, private; only the whites had ranks.[11] According to him there were 19 men involved, described by him as 14 "insurgents" and 5 "negroes"; he did not know about the three at the Kennedy farm.

A Voice from Harpers Ferry, 1861

The only one of the raiders to leave a memoir was Osborne Anderson, author of A Voice from Harpers Ferry.[12] He was the only one of the five Blacks to survive, and thus the only good source for information about the Black participants, whom most white participants said little of. It also was written immediately after the events.

Owen Brown interviewed in 1874

Another survivor, Owen Brown, avoided telling his story. He gave his memoirs of the episode fifteen years later, in an interview,[1] but he was not part of the Harpers Ferry action; he was a lookout at the Kennedy Farm in Maryland.

Israel Greene's recollections, 1888

Lt. Israel Greene led the company of Marines that broke down the door of Brown's fort. He was present on Tuesday and Wednesday.[13]

Joseph Barry's Strange Story of Harper's Ferry (1903)

Barry says on the cover that he was "a resident of the place [Harpers Ferry] for half a century". His books, in contrast to others, were intended for local sale to tourists among others, as it has advertisements for a hotel with steam heat and electric lights,[14]:203 a suggestion that the visitor visit the Dime Museum,[14]:202 and fishing guides and bait available on short notice.[14]:203 50 pages are on Brown's raid, and Brown's picture is on the cover.[14]

Surveys by later writers

- Richard J. Hinton, who became a newspaper reporter and editor, and later a geologist, was an "intimate friend" of John Brown in Kansas.[15] On occasion of the recovery of the body of Watson Brown in 1882, he published in his paper "a chapter as to what became of the others who were with Brown at Harper's Ferry".[16] In 1889 this became a magazine article,[17] and then 130 pages in his John Brown and His Men (1894).[18] Many of the sketched portraits in the gallery below are from this book. In 1899, after the conversion of the John Brown Farm to a public park, he summarizes his conclusions.[19][20]

- Thomas Featherstonhaugh, "John Brown's men" (1899).[21]

- Villard, Oswald Garrison (1910). "John Brown's Men-at-arms". John Brown, 1800-1859; a biography fifty years after. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. pp. 678–687.

- A person whose initials were ASR compiled in 1995 "The Conspirators [sic] Biographies".[22]

- Tony Horwitz, "The Toll from the Raid on Harpers Ferry", in Midnight rising : John Brown and the raid that sparked the Civil War (2011).[23]

- National Park Service, "John Brown's Raiders at Harpers Ferry" (2017).[24]

Other primary sources on the Harpers Ferry raid (in order of publication)

- Newspapers began publishing in October various signed and unsigned reports on the raid, the raiders, and the trials. For example, the entire first page and part of the second of the October 29th issue of the Anti-Slavery Bugle are filled with brief reports on the raid. The Bugle compared the assault on Harpers Ferry with the Battle of Bunker Hill against the British, in 1775.[25]

- The recollections of David H. Strother, better known by his pseudonym Porte Crayon, and who lived in nearby Berkeley Springs, appeared in Harper's Weekly in 1859.[26] A partial draft was published in 1965.[27]

- A Citizen of Harpers Ferry (1859). Startling incidents & developments of Osowotomy Brown's insurrectory and treasonable movements at Harper's Ferry, Virginia, October 17th, 1859 : with a true and accurate account of the whole transaction. (Requires subscription for access). Baltimore – via Adam Matthew Digital.

- The 1860 report of the Special U.S. Senate Investigative Committee, known as the Mason report from the name of its author and the committee chair, Virginia Senator James M. Mason, has little on the members of Brown's party. It is primarily focused on discovering who backed Brown and financed the raid.[28]

- Boteler, Alexander R. (1883). "Recollections of the John Brown raid, by a Virginian Who Witnessed the Fight". The Century Magazine. 26: 399–411.

- John Daingerfield, the Paymaster's Clerk who was one of the hostages, wrote his recollections, punlished in 1885.Daingerfield, John E. P. (1885). "John Brown at Harpers Ferry, as seen by one of his prisoners". The Century Magazine. 30: 265–267.

- Newton, John (1902). Captain John Brown of Harper's Ferry; a preliminary incident to the great civil war of America,. New York: A. Wessels.

- A member of the Shepherdstown militia, John H. Zittle, left (1905) "a living picture of the occurrences as they appeared to the people of the community at that time", but he had no direct knowledge of the raiders' identities.[29]

- Charles White, who was an eyewitness starting Monday the 17th, wrote his recollections, first published in 1959.[30]

- Father Costello, the Catholic priest Brown threw out of his cell, wrote his recollections, which were published in 1974.[31]

Ages

The oldest was Dangerfield Newby, at 44. Owen Brown was 35. All the rest were under 30. Oliver Brown, Barclay Coppoc, and William H. Leeman were under 21.[32]:702 John Brown was 59. The ages of the Blacks, such as Shields Green, vary considerably from one source to another, between 22 and 30.

Counts

Of Brown's party of 22, counting himself,

- 19 went to Harpers Ferry (Jerry Anderson, Osborne Anderson, John Brown, his sons Oliver and Watson Brown, Cook, Copeland, Edwin Coppock, Green, Hazlett, Kagi, Leary, Leeman, Newby, Stevens, Taylor, brothers Adolphus and William Thompson, Tidd)

- 3 (Owen Brown, Barclay Coppock, Meriam) remained at the Kennedy Farm in Maryland, "to guard the arms and ammunition stored on the premises, until it should be time to move them."[1]:344 All successfully escaped once they learned the raid was failing.

—————

- 10 were killed during the raid or died shortly after of their wounds (Jerry Anderson, Oliver Brown, Watson Brown, Kagi, Leary, Leeman, Newby, Taylor, Adolphus Thompson, William Thompson)

- 7 were tried and executed, 5 who were taken prisoner on the spot (John Brown, Cook, Copeland, Edwin Coppock, Green) plus 2 who escaped but were captured (Hazlitt, Stevens)

- 5 escaped north and were not captured (Osborne Anderson, Owen Brown, Barclay Coppock, Meriam, Tidd).

Three of Brown's sons participated in the raid. One, Oliver, was killed in the engine house, and another, Watson, was shot and died two days later. Owen Brown escaped and became an officer in the Union Army. Watson's body was recovered in 1882; Oliver's not until 1899. Salmon Brown, though he had been with his father and brothers in Kansas, did not want to participate in the Harpers Ferry raid and remained in North Elba, running the farm.[33]

Brown's daughter Annie Brown, who at the time was 15, and Oliver's wife Martha, 17, were at the Kennedy farm, doing the cooking and housekeeping while they "kept discreet watch over the prattling conspirators in the house and hustled them out of sight on occasion, and who turned aside local suspicion by their sweet and honest ways,"[34] John sent them home to North Elba on September 30.[35]

Black participation

Of the various contradictory reports made by slaveholders and their satellites about the time of the Harper's Ferry conflict, none were more untruthful than those relating to the slaves. There was seemingly a studied attempt to enforce the belief that the slaves were cowardly, and that they were really more in favor of Virginia masters and slavery, than of their freedom. As a party who had an intimate knowledge of the conduct of the colored men engaged, I am prepared to make an emphatic denial of the gross imputation against them..[12]:59

Of Brown's raiders, 17 were white and 5 (23%) were Black.[36] Of the five Blacks, two (Leary, Newby) died during the raid, two (Copeland and Green) were executed, and one (Osborne Anderson) escaped. Two (Green and Newby) had been enslaved and were fugitives; three (Osborne Anderson, Copeland, and Leary) were free blacks, but Copeland was a fugitive from the charge of participating in the 1858 Oberlin-Wellington Rescue, of which he was a leader.[9]:1787

Brown said many times that he had expected a large number of enslaved blacks to flee their owners and assist him in the raid and afterwards. This did not happen, a main reason for the raid's failure. However, Robert E. Lee's statement, in his "Report", that local blacks gave him no voluntary assistance at all,[11]:22 is not correct, though it appeared again in the Senate Special Committee report[37] and in many Southern reports on the raid. According to Virginia Governor Henry A. Wise, "not a slave around was found faithless".[38]:222 These "faithful slaves" who allegedly refused to help Brown at Harpers Ferry became a key element in the "Lost Cause" myth of happy Antebellum Southern life. The United Daughters of the Confederacy had later a "Faithful Slave Committee" trying to honor them with a monument in Harpers Ferry (see Hayward Shepherd Monument).

The True Bill of Indictment gives the names of 11 slaves whom the conspirators had incited to revolt, 4 of Lewis Washington (Jim, Sam, Mason, and Oatesby or Catesby), and 7 of Mr. Alstadt (Henry, Levi, Ben, Herry, Phil, George, and Bill), plus "other slaves to the jurors unknown".[39] Of those, we have clear documentation of two that were with Brown voluntarily. One was Jim, "a young coachman hired by Lewis Washington from an owner in Winchester";[38]:296–297 he drowned attempting to flee by crossing the river. "There is no doubt that Washington's negro coachman, Jim, who was chased into the river and drowned, had joined the rebels with a good will. A pistol was found on him, and he had his pockets filled with ball cartridges, when he was fished out of the river."[40]

Ben, who was owned by John Allstadt, was captured and almost lynched. He died in the Charles Town jail of "pneumonia and fright", along with his mother Ary, also owned by Allstadt, who had come to nurse him.[38]:397–398 Both owners filed claims with the government of Virginia for compensation for the loss of their "property" in the raid; it is not known if their claims were successful.[38]:326–327

These are not the only Blacks that fled their owners and participated in the raid. The first report on "insurrectionists" killed gave the number of 17, but only 10 were Brown's men, and the other 7 must have been liberated slaves helping him. In the engine house there were "a few negroes that had been liberated and armed by Brown".[41]:153 Except for Ben and Jim, their names are unknown. There were twelve or thirteen bodies inmediately buried, but only the names of eight are known.[42] There were other slaves killed whose bodies were carried away by the river.[12]:60 According to Louis DeCaro, at the peak there were 20 to 30 local slaves involved, who quickly and quietly went back to their masters' when it became clear the raid was failing.[43]:264

In Harpers Ferry, a Black Voices Museum, at 17 High Street, was operating in 2020.[44]

Burials

None of those killed (10) or executed (7) are buried in Harpers Ferry, Charles Town, or anywhere else in Jefferson County. Virginia Governor Henry A. Wise said he did not want those executed to be buried anywhere in Virginia, and none were.

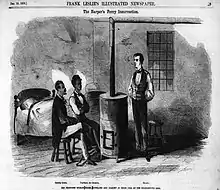

Three bodies—1 white (Jerry Anderson) and 2 Blacks (Copeland, Green)—were used for the dissection component of medical studies. The remains after the dissection were apparently discarded. In 1928, a pit containing bones of those dissected was found underneath the foundation of a building being torn down.[45] The medical students and faculty did not know, or care, who they were. Their fourth body, that of Watson Brown, was identified from papers in a pocket as one of Brown's sons, though they did not know which one. It was preserved by a medical school professor and made into an anatomical exhibit, labeled expressing the Virginians' attitude toward abolitionists, and toward John Brown in particular.

Except for those mentioned below as buried by relatives, and the 3 missing bodies that were dissected, the other raiders killed or executed in 1859–1860 are buried at the John Brown Farm State Historic Site, near Lake Placid, New York.

Note that while there were 10 men killed during the raid itself, and 10 bodies reburied together at the John Brown Farm, the 10 are not the same. 2 of the first 10 (Watson Brown, Jeremiah Anderson) were taken to the Winchester Medical College for use by medical students. To the 8 remaining were added the bodies of Hazlett and Stevens, part of the raid but tried and originally buried separately. A relative of Stevens had his and Hazlett's bodies disinterred from their graves in New Jersey, so they could be buried with the others.

Symbols

- ‡ The bodies of the 4 so marked were taken to Winchester Medical College for dissection by medical students.

- One was killed during the raid (Jerry Anderson): another died shortly after (Watson Brown), and two were tried and executed (Green and Copeland); the last two were African Americans. Except for Watson, the location of their remains is unknown. Medical schools in the South routinely used bodies of the enslaved for this purpose, citing the availability of such bodies as an incentive to enroll.[46]:183–184

- † marks the 10 buried in 1899 in a single coffin on the John Brown Farm in North Elba, New York, according to a plaque there.

- They include the remaining 8 of the 10 killed during the raid itself. Unwelcome in local cemeteries, they were thrown into two "store boxes", and a man was paid $5.00 to bury them, without ceremony, clergy, or marker, on the far side of the Shenandoah (in Clarke County). The family knew that Oliver was buried "by the Shenandoah", but no more.[47] Forty years later, the man who buried them was still alive, the unmarked pit was located, and the remains, which in most cases could not be matched to specific individuals, were taken to North Elba and buried in a single coffin.[48] The plaque says the remains of Jeremiah Anderson are there as well, but this is not correct; they are lost, as are those of the other two African Americans dissected.

- With those 8, in the same coffin and ceremony, were the remains of Hazlitt and Stevens, who had been executed, and whose bodies had been buried at the Eagleswood Military Academy in Perth Amboy, New Jersey.[49] A relative of Stevens had them disinterred so they could be buried with the others.

- ¶ indicates an African American.

Killed during the raid

- Bodies taken to Charles Town for dissection by medical students:

- ‡ Watson Brown, 24, John Brown's son, was mortally wounded outside the engine house while carrying a white flag to negotiate with the opposing militia. He was not shot by a Marine, as they respected the white flag, but by an infuriated townsman. He survived in agony for another day. His body was taken by Winchester Medical College, skinned, and preserved as anatomical specimen. When a Union army occupied Winchester in 1862, his body was "rescued" by a Union doctor, who had it shipped to his home in Indiana. It was returned to the family and buried in North Elba in 1882. See Burning of Winchester Medical College.

- ‡ Jeremiah Goldsmith "Jerry" Anderson, 26, from Indiana.[11]:24 He had been with Brown in Kansas. Brown was "attended, generally, in his movements about the city [Boston] and its neighborhood, by a faithful henchman, Jerry Anderson." He was killed by a Marine's bayonet during the final assault on the engine house. He had in his pocket a letter from his brother John J. (or G. or Q.) Anderson, of Chillicothe, Ohio.[50] His body was taken by Winchester Medical College;[48]:133 last resting place unknown.

- First buried in two unmarked boxes near Harpers Ferry; re-interred in 1899 in a common coffin in North Elba:

- † John Henry Kagi from Ohio, was with Brown in Kansas. He was shot and killed while attempting to cross the Shenandoah River. One report says mistakenly that his body was taken for dissection.[48]:133

- † William Thompson, from North Elba, N.Y. He was brother of Adolphus. He and his brother were brothers of Henry Thompson, who was married to Ruth, John Brown's eldest daughter.

- † Adolphus Dauphin Thompson, from North Elba, N.Y., was killed in the storming of the engine house. He was brother of William.

- † Oliver Brown, 21, the youngest of John Brown's three sons to participate in the action. He was described by his mother as the child "most like his father, caring most for learning of all our children."[51] He was mortally wounded on the 17th inside the engine house, and died beside his father.

- † Stewart Taylor, from Uxbridge, Ontario, Canada.

- † William Leeman, from Maine,[11]:24 youngest of all the raiders,[52] was shot and killed while trying to escape across the Potomac River. His sister, Mrs. S. H. Brown, published a letter of John Brown of November 28, 1859, which according to her had never been published. From it we learn he was killed not trying to escape, but on a message to deliver a message of John Brown to Owen Brown or Cook.[52]

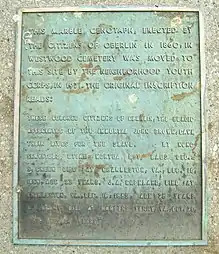

- †¶Lewis Sheridan Leary, a 24-year-old free black, uncle of Copeland, was from Oberlin, Ohio.[11]:24 "He said before he died that he enlisted with Capt. Brown for the insurrection at a fair held in Lorraine County, Ohio, and received the money to pay his expenses."[53]:30 He was mortally wounded while trying to escape across the Shenandoah River. He was stationed in the rifle factory with Kagi. John Copeland was his nephew. There is a cenotaph memorial in Oberlin, Ohio.

- †¶ Dangerfield Newby, about 35, from Ohio,[11]:24 was born into slavery, with a white father who was not his owner. He was given permission to move to Ohio along with his mother and siblings, but when he tried to gain freedom for his wife and children, their owner refused. to sell them even after Newby had earned and saved the agreed-upon price. This inspired Newby to join Brown's raid. He was the first raider killed. His body was mutilated: his ears and genitals were cut off as souvenirs.[54] As it lay in the street for over 24 hours, hogs wereeating it. One son was Rev. Dangerfield F. Newby, Jr. (1855–1936).[55]

- Disposition of body unknown

- ¶Jim, who Brown's men had freed from Lewis Washington, who leased Jim from his owner.. According to Barry he was killed while trying to escape,[14]:83 which must have meant attempting to swim the river, and his body was presumably carried away downstream.

Captured, tried, convicted, and executed by hanging

In the Charles Town jail, by one report, Brown and Hazlett shared a room and a bed, Green and Coppock another, manacled together, and Copeland was in a third room. The rooms in the jail were described as "very large and nicely kept".[56]

Brown was executed on Friday, December 2, four others on December 16, 1859, the negroes (Copeland, Green) in the morning and the whites (Cook, Coppock) in the afternoon,[57] and two (Hazlitt, Stevens) on March 16, 1860. Cook and Coppock attempted to escape, but did not get over the jail wall.[58]

- Buried by relatives

- John Brown, 59. His widow took his body to North Elba, and buried him there. On the transportation of his corpse, which was not uneventful, see John Brown (abolitionist)#Transportation of his body.

- Edwin Coppock 24, shot and killed the mayor of Harpers Ferry, Fontaine Beckham, during the raid. He had been with John Brown in Kansas.[59] A newspaper report says that his body was sent to his mother in Springdale, Iowa,[60] another that it was sent to a Thomas Winn in Springdale,[57] accompanied by his uncle, "a highly esteemed old Quaker gentleman, who did not sympathize in the least with the misguided and errant young man, and by him [the body was] conveyed to the home of his afflicted mother."[57] A different report says that the Quaker was not a relative, but someone who took him in when he became an orphan.[59][53]:27 However, findagrave.com reports that he was buried in his abolitionist home town of Salem, Ohio, where there is a plaque on a commemorative pillar.[61]

- John Edwin Cook, 29, born in Haddam, Connecticut,[62] but from Pennsylvania.[11]:24 He had been a teacher.[63] He was Brown's second in command, by one report.[64] He was described as "a man of some intelligence'.[64] He escaped into Pennsylvania after the raid but was soon captured. Cook was the only one captured who gave testimony about the other raiders;[65] his testimony at his trial was immediately published as a pamphlet.[6][66] Convicted, he was hanged December 16, 1859 in Charles Town. Two of his sisters were present, as were his brother-in-law, Governor Ashbel Willard of Indiana, and one of his attorneys, Daniel W. Voorhees, U.S. Attorney for Indiana.[67][60] Body sent to A. P. Willard, care of Robert Crowley, Williamsburg, New York.[57] First buried in Cypress Hill Cemetery, Brooklyn, New York, he was later reburied in Green-Wood Cemetery, also in Brooklyn.

- Bodies immediately dug up by students of the Winchester Medical College. "They were allowed to remain in the ground but a few moments, when they were taken up and conveyed to Winchester for dissection."[68] A letter from Black residents of Philadelphia to Governor Wise, requesting their bodies so as to bury them, had no effect.[69]

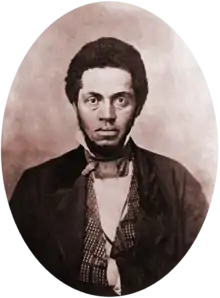

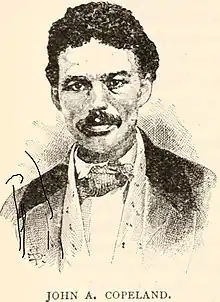

- ঠJohn Anthony Copeland, Jr., a 24-year-old free Black, described as a mulatto,[62] joined the raiders along with his uncle Lewis Leary. Of Brown's raiders, only Copeland was at all well known. As a leader of the Oberlin-Wellington fugitive slave rescue, he was notorious in Ohio, and was a fugitive from an indictment for his role in that rescue.[9] His parents attempted unsuccessfully to recover his body. On December 29, 3,000 attended a bodyless funeral in Oberlin, Ohio.[70] The last resting place is unknown. Cenotaph memorial in Oberlin.

- ঠShields Green, 22,[62] was an escaped Black slave from South Carolina. He was captured in the engine house on October 18, 1859 and hanged December 16, 1859 in Charles Town. The body was claimed by Winchester Medical College as a teaching cadaver. The last resting place is unknown. Cenotaph memorial in Oberlin, Ohio.

- Buried at Eagleswood Military Academy in Perth Amboy, New Jersey, a school founded by abolitionists Rebecca Buffum Spring and her husband Marcus Spring, and directed for a time by Theodore Weld. In 1898 they were reinterred with eight others at the John Brown Farm in North Elba, New York.[49]

- † Albert E. Hazlett escaped into Pennsylvania but was soon captured. Executed March 16, 1860.

- † Aaron Dwight Stevens (Lee has Aaron C. Stevens), from Connecticut,[11]:24 29, shot and captured October 18. Executed March 16, 1860.

Captured, died in jail

- ¶Ben (Allstadt), freed by Brown's men from his owner, John Allstadt. His mother Ary, also belonging to Allstadt, came to the jail to nurse him and also died there.

Escaped and never captured

- Barclay Coppock, 22 or 23,[1]:345 from Iowa like his brother,[11]:24 died in the Union Army, 1861.

- Charles Plummer Tidd, a "lumberman" from Maine,[11]:24 had been with Brown in Kansas.[1]:345 He died during the Civil War, 1862.

- ¶Osborne Perry Anderson served as a recruiter for the Union Army, and wrote a memoir about the raid.[12] Died in 1872.

- Owen Brown served as an officer in Union Army. He died January 8, 1889 in Pasadena, California (Brown's Mountain).

- Francis Jackson Meriam, 28 or 30, "of the wealthy Massachusetts Meriams",[1]:345 who "had furnished a good deal of money to the cause",[1]:358 served in the Union army as a captain in the 3rd South Carolina Volunteer Infantry Regiment (Colored). (Colored regiments had white officers.) He died of natural causes[1]:358 in 1865.

Gallery (alphabetical)

Oliver Brown

Oliver Brown Owen Brown

Owen Brown

John Edwin Cook

John Edwin Cook

Albert Hazlett

Albert Hazlett William Henry Leeman

William Henry Leeman

.jpg.webp) Francis Jackson Meriam

Francis Jackson Meriam

Dauphin Adolphus Thompson

Dauphin Adolphus Thompson William Thompson

William Thompson Charles Plummer Tidd

Charles Plummer Tidd

References

- Keeler, Ralph (March 1874). "Owen Brown's Escape From Harper's Ferry". Atlantic Monthly: 342–365.

- Manning, J[acob] M. (November 25, 1859). "Speech of Rev. J. M. Manning, of the Old South Church". The Liberator (Boston, Massachusetts). p. 2 – via newspapers.com.

- "John Brown's Men. What Became of Those Who Followed the Old Hero to the Destruction of Slavery at Harpers Ferry—"The Blow Heard Around the World", October 16 to 19, 1859". Sandusky Daily Register (Sandusky, Ohio). November 9, 1882 – via newspaperarchive.com.

- Barry, Joseph (1869). The annals of Harper's Ferry, from the establishment of the national armory in 1794 to the present time, 1869. Hagerstown, Maryland. p. 35.

- Lubet, Steven (2012). John Brown's Spy. The Adventurous Life and Tragic Confession of John E. Cook. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300180497.

- Cook, John Edwin (November 11, 1859). Confession of John E. Cooke [sic], brother of Gov. A.P. Willard, of Indiana, and one of the participants in the Harper's Ferry invasion : published for the benefit of Samuel C. Young, a non-slaveholder, who is permanently disabled by a wound received in defence of Southern institutions. Charles Town, Virginia: D. Smith Eichelberger, Editor of the Independent Democrat.

- Lubet, Steven (2015). The "Colored Hero" of Harper's Ferry: John Anthony Copeland and the War Against Slavery. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781139872072.

- DeCaro, Louis A (2020). The untold story of Shields Green : the life and death of a Harper's Ferry raider. New York: New York University Press. ISBN 9781479802753.

- Lubet, Steven (June 1, 2013). "Execution in Virginia, 1859: The Trials of Green and Copeland". North Carolina Law Review. 91 (5): 1785–1815, at p. 1788.

- United States Congress. Senate. Select Committee on the Harper's Ferry Invasion (June 15, 1860). "Testimony". In Mason, John Murray (ed.). Report on the Harper's Ferry Invasion. Retrieved January 13, 2021.

- Lee, Robert E. (July 1902). "Col. Robert E. Lee's Report. Headquarters Harper's Ferry. October 19, 1859". The John Brown Letters. Found in the Virginia State Library in 1901 (continued). Virginia Magazine of History and Biography. 10. pp. 17–32, at pp. 18–25. JSTOR 4242480.

- Anderson, Osborne P. (1861). A voice from Harper's Ferry : a narrative of events at Harper's Ferry : with incidents prior and subsequent to its capture by Captain Brown and his men. Boston: The author.

- Green[e], Israel (December 1885). "The Capture of John Brown". North American Review: 564–569.

- Barry, Joseph (1903). The Strange Story of Harpers Ferry. Martinsburg, West Virginia.

- "A friend of old Osawatomie". Nebraska State Journal (Lincoln, Nebraska). April 30, 1889. p. 2 – via newspapers.com.

- "John Brown's Raid. Interesting reminiscences of Harpers Ferry". Topeka Daily Capital (Topeka, Kansas). October 4, 1882. p. 2 – via newspapers.com.

- Hinton, R[ichard] J[osiah] (June 1889). "John Brown and his men, before and after the raid on Harper's Ferry, October 16th, 17th, 18th, 1859". Frank Leslie's Popular Monthly. 2 (6): 691–703.

- Hinton, Richard J (1894). "John Brown's Men—Who They Were," and "Men who Fought and Fell, or escaped". John Brown and his men ; with some account of the roads they traveled to reach Harper's Ferry (Revised ed.). New York: Funk & Wagnalls. pp. 449–582.

- Hinton, Richard J. (September 18, 1899). "John Brown's comrades". New-York Tribune. Part 1 of 2. p. 6 – via newspapers.com.

- Hinton, Richard J. (September 18, 1899). "John Brown's comrades". New-York Tribune. Part 2 of 2. p. 7 – via newspapers.com.

- Featherstonhaugh, Thomas (October 1899). "John Brown's Men: The Lives of Those Killed at Harper's Ferry, with a Supplementary Bibliography of John Brown". Southern History Association. 3 (1): 281–306.

- ASR (March 21, 1995). "The Conspirators [sic] Biographies".

- Horwitz, Tony (2011). "The toll from the raid on Harpers Ferry". Midnight rising : John Brown and the raid that sparked the Civil War. Henry Holt and Co. pp. 290–291. ISBN 9780805091533.

- Harpers Ferry National Historical Park (December 28, 2017), John Brown's Raiders at Harpers Ferry, National Park Service, retrieved December 5, 2020

- "The Fruit Maturing". Anti-Slavery Bugle (Lisbon, Ohio). October 22, 1859. p. 3 – via newspapers.com.

- Strother, D. H. (November 5, 1859). "The Late Invasion at Harper's Ferry". Harper's Weekly. 3: 712–714.

- Strother, D. H. (April 1965). Ely, Cecil D. (ed.). "The Last Hours of the John Brown Raid: The Narrative of David H. Strother". Virginia Magazine of History and Biography. 73 (2): 169–177. JSTOR 4247105.

- Mason, James M.; Collamer, Jacob (June 15, 1860). Report [of] the Select committee of the Senate appointed to inquire into the late invasion and seizure of the public property at Harper's Ferry.

- Zittle, John Henry (1905). Zittle, Hanna Minnie Weaver (ed.). A correct history of the John Brown invasion at Harper's Ferry, West Va., Oct. 17, 1859. Compiled by the late Capt. John H. Zittle, of Shepherdstown, W. Va., Who was an Eye-Witness to many of the occurrences, and edited and published by his widow. Hagerstown, Maryland.

- White, Charles (October 1959). "John Brown's Raid at Harper's Ferry: An Eyewitness Account By Charles White". Virginia Magazine of History and Biography. 67: 387–395.

- Costello, Michael A. (March–June 1974). =Ely Jr., James W.; Jordan, Daniel P. (eds.). "Harpers Ferry Revisited: Father Costello's 'Short Sketch' of Brown's Raid". Records of the American Catholic Historical Society of Philadelphia. 85 (1/2): 59–67. JSTOR 44210849.

- Lawson, John D. (1916). "The Trial of John Brown for Treason and Insurrection, Charlestown, Virginia, 1859". American state trials : a collection of the important and interesting criminal trials which have taken place in the United States from the beginning of our government to the present day. 6. St. Louis: Thomas Law Books. pp. 700–805.

- Brown, Salmon (June 1935). "John Brown and Sons in Kansas Territory". Indiana Magazine of History. 31 (2): 142–150. JSTOR 27786731.

- Chamberlin, Joseph Edgar (1899). John Brown,. London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner & Co. p. 108.

- Harpers Ferry National Historical Park (December 27, 2017), John Brown's raid, National Park Service, retrieved December 5, 2020

- Love, Rose Leary (April 1964). "The Five Brave Negroes with John Brown at Harpers Ferry". Negro History Bulletin. 27 (7): 164–169. JSTOR 44177040.

- United States Congress. Senate. Select Committee on the Harper's Ferry Invasion (June 15, 1860). "Report". In Mason, John Murray (ed.). Report on the Harper's Ferry Invasion. Same text is more legible here. Note that each section has separate pagination. p. 7.

- Horwitz, Tony (2011). Midnight Rising: John Brown and the Raid That Sparked the Civil War. Henry Holt and Company. ISBN 978-0805091533.

- "The Bill of Indictment found against the prisoners". New York Daily Herald. October 30, 1859. p. 1 – via newspapers.com.

- "News, Rumors, and Gossip from Harpers Ferry". New York Daily Herald. More legible here. November 1, 1859. p. 3 – via newspapers.com.CS1 maint: others (link)

- "The Execution of Old John Brown. Full particulars of the prison and gallows scene. Old Brown's Will. He writes his own epitaph. In the Last interview with his wife and fellow-prisoners, &c. &c". Chicago Tribune (Chicago, Illinois). December 5, 1859. p. 1. Archived from the original on December 9, 2020. Retrieved November 27, 2020 – via newspapers.com.

- DeCaro, Louis (2002). "Fire from the Midst of You": A Religious Life of John Brown. New York: NYU Press. ISBN 978-0814719220. Retrieved August 1, 2020.

- "Black Voices Museum". Facebook. Retrieved December 27, 2020.

- "Finds Cemetery in Backyard; Bones May Be Those of John Brown's Men". Richmond Times-Dispatch (Richmond, Virginia). April 8, 1928. p. 1 – via newspapers.com.

- von Daacke, Kirt (2019). "Anatomical Theater". In McInnis, Maurie D.; Nelson, Louis P. (eds.). Educated in Tyranny: Slavery at Thomas Jefferson's University. University of Virginia Press. pp. 171–198. ISBN 978-0813942865.

- "Watson Brown's Remains". Indianapolis Journal. October 18, 1882. p. 2 – via newspaperarchive.com.

- Featherstonhaugh, Thomas (March 1901). "The Final Burial of the Followers of John Brown". New England Magazine. 24 (new series) (1): 128–34.

- "John Brown's Men Disinterred". New York Times. August 29, 1899. p. 1.

- "Incidents of the second battle". Baltimore Sun. 19 October 1859. p. 1. Archived from the original on August 29, 2020. Retrieved August 26, 2020 – via newspapers.com.

- S[pring], R[ebecca] B[uffin] (December 2, 1859). "A Visit to John Brown by a Lady". New-York Tribune. p. 6 – via newspapers.com.

- "The John Brown Raid". Century Magazine. 26: 958. 1883.

- De Witt, Robert M. (1859). The Life, Trial and Execution of Captain John Brown, Known as "Old Brown of Ossawatomie," with a full account of the attempted insurrection at Harper's Ferry, Virginia. Compiled from official and authentic sources. Inducting Cooke's Confession, and all the Incidents of the Execution. New York: Robert M. De Witt.

- Korda, Michael (2014). Clouds of Glory : The Life and Legend of Robert E. Lee. An excerpt, "When Robert E. Lee Met John Brown and Saved the Union", was published in The Daily Beast. Harper. p. xxix. ISBN 978-0062116314.

- Rev Dangerfield F Newby Jr., findagrave.com, 2010, retrieved December 27, 2020

- "The Prisoners in jail". The States and Union (Ashland, Ohio). November 9, 1859. p. 4 – via newspapers.com.

- "Execution of the Insurgents". Star and Enterprise (Newville, Pennsylvania). December 22, 1859. p. 2 – via newspapers.com.

- Drew, Thomas (1860). "The John Brown invasion; an authentic history of the Harper's Ferry tragedy, with full details of the capture, trial, and execution of the invaders, and of all the incidents connected therewith. With a lithographic portrait of Capt. John Brown, from a photograph by Whipple". Boston: James Campbell.

- "(Untitled)". Herald of Freedom (Lawrence, Kansas). November 19, 1859. p. 2 – via newspaperarchive.com.

- "(Untitled)". Herald of Freedom (Lawrence, Kansas). December 17, 1859. p. 2 – via newspapers.com.

- "Edwin Coppock". findagrave.com. Retrieved October 25, 2020.

- "Ages of the prisoners". The Liberator (Boston, Massachusetts). December 23, 1859. p. 3 – via newspapers.com.

- "The Late Rebellion". The Daily Exchange (Baltimore, Maryland). October 19, 1859. p. 1 – via newspapers.com.

- "Operation of state and national troops". Anti-Slavery Bugle (Lisbon, Ohio). October 29, 1859. p. 1 – via newspapers.com.

- Lubet, Steven (2013). John Brown's spy : the adventurous life and tragic confession of John E. Cook. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300180497.

- "John Brown's Invasion. Cook's confession". New-York Tribune. November 26, 1859. p. 7 – via newspapers.com.

- "The Harper's Ferry invasion. Cook, Coppic, Green, and Copeland to be Executed To-day. Preparations for the event". Detroit Free Press (Detroit, Michigan). December 16, 1859. p. 1 – via newspapers.com.

- "(Untitled)". Cleveland Daily Leader (Cleveland, Ohio). December 22, 1859. p. 2 – via newspapers.com.

- "Request to Gov. Wise to get the bodies of the colored men to be executed to-day". The Liberator (Boston, Massachusetts). December 23, 1859. p. 3 – via newspapers.com.

- Finkleman, Paul (1995). "Manufacturing Martyrdom. The anti-Slavery Response to John Brown's raid". In Finkleman, Paul (ed.). His Soul Goes Marching On. Responses to John Brown and the Harpers Ferry Raid. Charlottesville, Virginia: University Press of Virginia. pp. 41–66, at p. 50. ISBN 0813915368.

- New York State Archives, Plaque at John Brown Grave Site, North Elba, 1920

- Anderson, John Q. (November 23, 1859), Letter to John Brown, Kansas Memory

- Both Coppack photos from A topical history of Cedar County, Iowa, Volume 1 (1910) Clarence Ray Aurner, S. J. Clarke Publishing Company